|

|

||

|

J. J.

Newberry's "dimestore" 815 Franklin St. at Polk St.

One O'Clock Jump, Count Basie & his Orchestra, 1947 |

||

|

An Era of Peace and Prosperity When the war ended, Tampa worried for a time over the possibility that a wave of unemployment would follow the return of thousands of servicemen and the suspension of activities in the shipyards. But a serious unemployment problem did not arise. A large percentage of the shipyard workers had come to Tampa from other places and when shipyard operations ceased, most of the outsiders drifted away, probably returning to their former homes. As for the servicemen, they were quickly absorbed by a Tampa which soon began enjoying record growth. Tampa prospered along with all other communities in the bay area. The prosperity was due almost entirely to the fact that the removal of wartime travel restrictions released a flood of winter visitors eager to bask in the Florida sunshine. Northerners invaded Florida by the millions. In addition to vacationers, there came many thousands who had retired and desired to spend the remainder of their lives in a milder climate. Wide adoption of pension plans throughout the nation had greatly increased the number of persons who were financially able to retire, and Florida benefitted to a marked degree. Real estate values in Tampa began to advance rapidly soon after the end of the war. This was partly due to the removal from the market of “distress properties”—boom-time constructed buildings which had been taken over by bond holders after the Florida crash during the national depression. On May 11, 1943, the Floridan Hotel, built in 1926 by a company headed by A. J. Simms and later acquired by the Collier Florida Coast Hotel co., was purchased by a group of 12 persons including children of Paul H. Smith and Julian L. Cone. This group formed the Floridan Hotel Operating Co., which on February 24, 1946, purchased the Thomas Jefferson Hotel, rebuilt and greatly enlarged in 1926 by Logan Bros. Purchase price for the 162 room Thomas Jefferson was reported to be $250,000. During the summer of 1944 a syndicate headed by Julian L. Cone acquired the Stovall Professional Building which had been built in 1925 by W. F. Stovall. In October of 1944, they also purchased the Citizens Building, built in 1926 by the Citizens Bank & Trust. Other buildings erected during the 1920s boom by Col. Stovall were sold at a foreclosure sale in February, 1945, to the Crest View Realty Company. These sales included the Wallace S. Building, Stovall Office Building, Haverty Furniture Co. Building, and others. The principal stockholders in the reorganized Crest View Realty Co. were Julian Cone, Howard Frankland, Paul Smith, C.T. Dawkins, Sam Flom, W. F. Stovall and W.O. Stovall. Col. Stovall was made president. On June 3, 1948, the Stovall Office building was sold for enough to pay all of the company’s indebtedness. All the unsold lots on Davis Islands, the Davis Islands Country Club, and stock of the Davis Islands, Inc., were purchased on October 22, 1945 by a syndicate composed of Howard Frankland, J.H.L. French, Wallace Tinsely and Alfred Dana. The syndicate acquired nearly a thousand lots and the purchase price was not disclosed. The Tampa Terrace Hotel was purchased on February 7, 1946 by a syndicate composed of Mrs. Angeles Corral, widow of the late Manuel Corral, and fifteen other persons. To operate the hotel, Overlord Inc. was organized. The Sunshine Race Track, built during the boom at a cost of $1.25 million and forced to close because of over-zealous law enforcement officials, was acquired in 1946 by a company headed by John W. Kane of Wilmington, Delaware and C. C. Vega, Jr., and reopened January 23, 1947. The racetrack has since become the West Coast’s major attractions, each season showing improvement in the quality of racing and amount of mutual play. Investment in expensive properties was only one of the signs of returning prosperity to the West Coast at the end of the war. A building boom developed throughout the Tampa Bay area which was comparable in magnitude o the building boom of the 1920s, but fortunately without speculative aspects. Every community spurted ahead. Tampa wholesale firms which sold building supplies did a land-office business. And so did the wholesalers and distributors of all types of consumer goods for which the public had developed a hunger during the war years. In helping to satisfy that hunger, Tampa business firms thrived amazingly. Prosperity for Tampa also came from the decision of the army to retain MacDill Field as a permanent air base because of excellent year-round flying weather and because it provided an unexcelled base for bombers needed to patrol the Gulf and Caribbean. In 1950, MacDill was staffed by 5,500 military men and 1,000 civilians, bringing into Tampa a monthly payroll which exceeded even that of the cigar industry. A large percentage of servicemen and civilian employees had families, and a strong demand for homes developed, particularly in the Interbay district. Drew field was inactivated soon after the war ended and on March 1, 1946, was turned over by the federal government to the city and immediately converted into a municipal airport. National Airlines began using the airport on April 25 and Eastern Airlines on May 1. The name of the field was changed to Tampa International Airport on October 15, 1947. See history of Drew Field and Tampa International Due to action taken by Tampa’s city officials, land adjacent to Drew Field which had been acquired by the army, did not revert to private ownership. On August 25, 1949, the city purchased 720 acres from the government for $70, 400, intending to use it for the development of a mammoth sports center, plans for which were still in the discussion stage in 1950. This became the site of Tampa Stadium in the 1960s. A broad program of public works projects, vitally needed to take care of Tampa’s increased population and to provide for future growth, was launched soon after the war’s end. Given top priority was a $3.5 million waterworks improvement program, work on which was completed in 1949. This was to assure Tampa of an adequate supply of water even during the most extended droughts and gave the city a waterworks system said to be surpassed by no other city of comparable size in the nation. After long years of talking and controversy, Tampa took positive steps in 1949 to solve its sewage problem. Back in 1915 during Mayor D. B. McKay’s administration, an excellent Imhoff disposal system was provided but the city’s totally unexpected growth during the booming 1920s caused the system to be overtaxed. Sewers bubbled up all over town and the resultant stench was often un bearable. Even worse, the waters of the Hillsborough River and Bay were dangerously polluted. City officials had made plans for a $13 million master sewerage system, to be financed by a special tax. Contracts were awarded during the summer of 1949 which totaled $3,221,834. Work was started on December 12, 1949. When completed, the system was to substantially reduce the pollution in the river and bay. The complete solution to lessening pollution was indefinitely delayed in late December of 1949 by the abandonment of plans for a sewerage system in the Interbay district. To lessen traffic congestion between downtown Tampa and Six Mile Creek, the city made rapid progress during 1949 in acquiring its portion of the right-of-way needed for the extension of Frank Adamo Drive. The county also took steps to acquire a three mile strip needed to extend the drive to Lake Wales Road. The State Road Department already had agreed to carry the highway eastward from that point, thereby providing a badly needed artery direct to the populous sections of central and east Florida. Tampa became the owner of valuable waterfront facilities as a result of cessation of shipyard activities. The shipbuilding plant of McCloskey & Co. on Hooker’s Point, including 131 acres of land, was purchased on April 16, 1947 for $425,000. Title to the property rested in the Hillsborough County Port Authority, established by an act of the state legislature on June 11, 1945. The original members of the board were Bruce Robbins, Richard Knight, F. M. Hendry, Byron Bushnell and Morris White. By 1950, Robbins and White were succeeded by Dave Gordan and Carleton C. Cone. By the end of 1949, the port authority had rented land and equipment to 15 dissimilar business concerns which added materially to the city’s payrolls. Rapid growth of the University of Tampa followed the close of the war. When President Nance took charge in the spring of 1945, enrollment was down to less than 200. It shot upward fast when veterans began taking advantage of the educational opportunities offered by the government. More than 1,100 students were enrolled in the fall of 1949. In 1941, the county commissioners improved the university’s financial state by allotting $15,000 annually to its support. This was later increased to $25,000. More help came when Dr. Nance succeeded in raising $65,000 from civic clubs, churches and individuals for new furnishings and improvements. Dr. Nance also stressed the pressing need for raising an endowment fund of at least $500,000. Two drives were conducted and by the end of 1949, the goal was almost in sight. Hillsborough County’s ancient courthouse in the heart of the business district, built in 1891, was doomed by the county commissioners during 1949 when they approved plans for a new building to be erected on the two blocks bounded by Lafayette, Pierce, Twiggs and Jefferson. Ground occupied by the old Madison Street School was taken over and private properties were purchased at a cost of $160,000. Work demolishing the buildings at the new courthouse site was started late in 1949. The estimated cost of the new courthouse was $2,355,000. It was to be financed by a one mil tax levy which during the two years prior to 1949 brought in $985,000. County commissioners planned to award a construction contract in 1950. Demolition on the old courthouse on the northeast corner of Franklin St. and Lafayette took place in April of 1953. See demolition photos from 1953 In Ybor City, plans were being made in late 1949 for restoring the Spanish atmosphere of the business section. Many of the beautiful balconies, decorated with iron grill work, which formerly adorned the buildings, had been torn down through the passing years in so-called modernization programs and as a result, Ybor City had lost much of its old-world charm. The proud Latins believed that if a restoration program could be carried out, possibly with federal assistance, Ybor City would attract almost as many sightseers as the French Quarter of New Orleans, particularly since Ybor City’s Spanish restaurants had become nationally famous. Because of the Latin-Americans, Tampa long before had acquired a cosmopolitan atmosphere equaled by few other cities of the country. Also because of the Latins, Tampa had some of the finest clubs which did much to add to the culture of the city. These clubs were among the pioneers of group health insurance in the United States. Years before, they had adopted plans for assuring all their members adequate medical and hospital care in case of illness. The leading Latin clubs were the Centro Asturiano, Centro Espanol, Circulo Cubano and Club Italia. The cigar industry, for which Ybor City was founded in 1885, furnished employment in 1949 for about 7,000 men and women, mostly Latin-Americans. The total was about 6,000 fewer than in the 1920s, due largely to the introduction of cigar making machines. Approximately the same number of cigars were being produced with 7,000 employees in 1949 as had been produced 20 years before with 13,000. Keen competition had caused the death of many small concerns, the number of factories had plunged from 159 in 1927 to 18 in 1949. All except three of the remaining factories operated union shops, the union having made a strong comeback during the 1930s. Latin-Americans who came to Tampa because of the cigar industry were no longer entirely dependent upon it. Relatively few members of the second generation turned to the cigar factories for life jobs; they preferred to enter other lines of endeavor where the pay was better and opportunities for advancement greater. By 1950, their occupations were as diversified as those of their Anglo-American friends and neighbors. Although the cigar industry was still Tampa’s leading industry, it did not bring in as much money to the city as the government’s operation of the air base at MacDill Field. Moreover, Tampa had long since ceased to be a one-industry town. Because of the proximity of rich phosphate deposits, the manufacture of fertilizer had become a major importance by 1950. The industry was pioneered in 1904 by Lemuel R. Woods, founder of the Gulf Fertilizer Company, and since then several other large companies had entered the field, notably the Lyons Fertilizer Co. and the West Coast Fertilizer Co. In addition the U.S. Phosphoric Products Co. had a multi-million dollar plant on the Alafia River. All these had large payrolls and brought much money into Tampa. Another major industry was the manufacture of cement by the General Portland Cement Co., formerly known as the Florida Portland Cement Co., which had an immense plant on the east side of Sparkman Channel and produced most of the cement used in Florida. Since the big freeze of 1894-95, Tampa had become one of the principal centers of Florida’s mammoth citrus industry. Headquarters of the Florida Citrus Exchange, one of the state’s larges cooperatives, had been maintained in Tampa since the organization was founded in 1909. The Exchange owned the building in which its general offices were located, at 110 Oak Avenue. Numerous packing plants were also located in and near Tampa, as well as several of the state’s largest manufacturers of citrus juices and concentrates. Tampa’s highly productive back country, in which millions of dollars of truck produce were grown each winter for northern markets, had long been a major factor in Hillsborough County’s economy. Plant City had been noted for many years as being the home of winter strawberries, and on the rich farms in that locality, tremendous quantities of celery, string beans, cabbage, peppers, and many other vegetables were produced each year. In the 1940s, the Ruskin district had made tremendous strides and was widely known as the tomato center of the state and the nation’s salad bowl. Of utmost importance to the city was the fact that Tampa had the finest harbor on the entire Gulf and was nationally recognized as a leading gateway to Central and South America. During the period of 1937 through 1941, outbound shipments averaged 1,470,000 tons. The need for making still further improvements was recognized by the Corps of Engineers and Congress during 1949 in approving plans for projects totaling $7,836,000. When completed, channels into Tampa’s harbor and into Port Tampa would have a minimum depth of 34 feet and would be greatly widened. In early 1950, Tampa was being served by steam ships owned by the Waterman Steamship Corp., Lykes Bros., Steamship Co. Inc., Luckenbach Gulf Steamship Co., Alcoa Steamship Co., Agwiline Inc., and many smaller companies. Also, steamships owned by foreign companies were regular arrivals at the harbor. Storms and Hurricanes in the 30s and 40s The strongest winds recorded in Tampa up until 1950, were recorded at 75 mph, taking place during the hurricane of September 3 – 5, 1935. The barometric pressure dropped to 29.31 inches. The highest tide for this storm was 5.3 feet and 7.31 inches of rain fell. The lowest pressure on record was registered during the hurricane of October 18-19, 1944 when it dropped to 28.55 inches. The storm was centered six miles east of Tampa. Tampa’s record rainfall occurred June 23-24, 1945 when 10.41 inches fell in 24 hours. Traces of snow during this era were recorded in Tampa in December of 1934, January 1940 and 1948. |

|

||

|

|

|||

Crowds at Cinema Theatre (formerly the Rialto) at 1621 Franklin St, 1945 |

|||

Hotel Thomas Jefferson at 117 Franklin St. at Washington St. |

|||

Ladies onboard a trolley in the early 1940s |

|||

In August of 1946, the Tampa Electric streetcars were retired to this yard in favor of city buses. |

|||

Tampa City bus interior, 1945 |

|||

The Sulphur Springs Hotel arcade at 8100 Nebraska Ave., 1946 |

|||

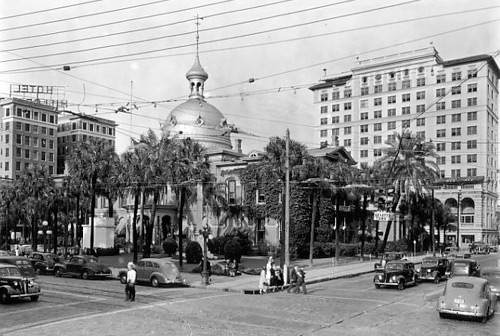

The Hillsborough County Courthouse at Franklin St. & Lafayette Streets, with the Hotel Tampa Terrace on the right and Hotel Hillsborough on the left, 1946 |

|||

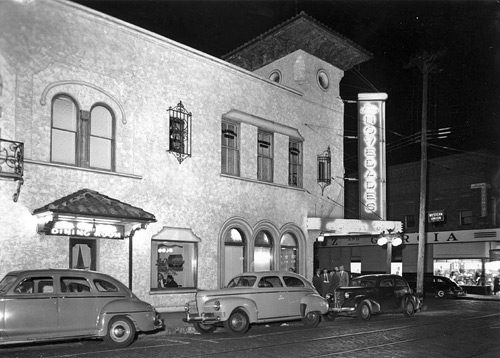

Las Novedades Restaurant at 1428 7th Ave., Ybor City, 1947 |

|||

Boxing cigars at Cuesta-Rey, 2015 Howard Ave., West Tampa, 1947 |

|||

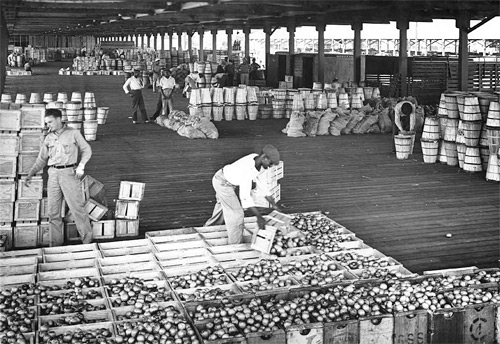

Loading citrus in a Tampa warehouse, 1947 |

|||

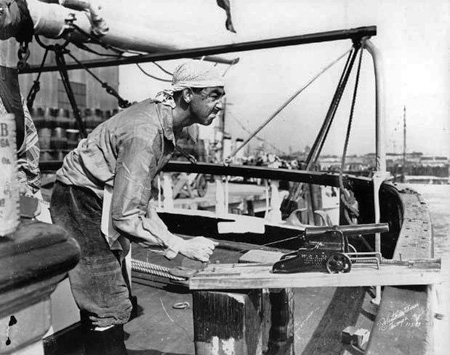

Dock workers with a shipment of bananas, Port of Tampa, 1940s |

|||

|

|

|||

|

|||

|

|

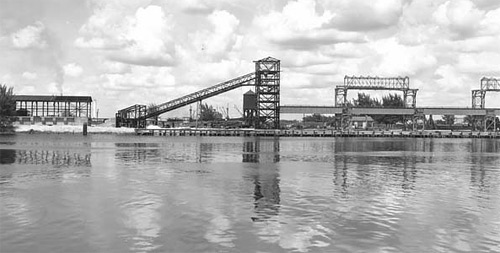

Phosphate elevator on Seddon Island (now Harbour Island), 1947 |

||

|

|

|||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|||

|

|

|

||

Cesar Gonzmart of the Columbia Restaurant 1948 |

Waitresses at the bus station lunch room, Jan. 20, 1948 Courtesy of Burgert Bros. collection, Tampa-Hillsborough County Public Library System |

||

Page1 | Page2 | Page3 | Page4 | Page5 | Page6 | Page7 | Page8 | Tampapix Home