|

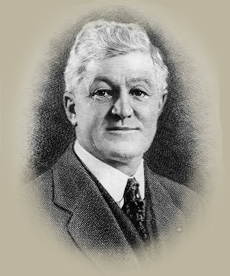

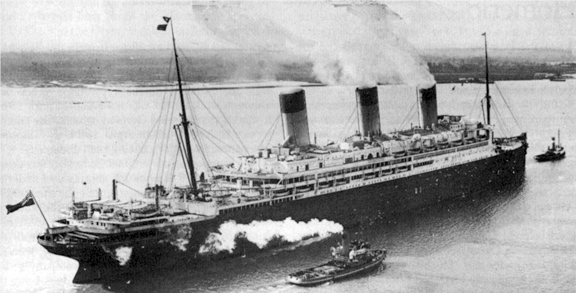

DAVID PAUL DAVIS AND HIS ISLANDS Read more about D.P. Davis' ancestry and history in Florida in this book by Rodney Kite Powell, where most of the information presented below are direct quotations of. David Paul Davis was born in Green Cove Springs, Florida on Nov. 19, 1885 and was educated in the public schools of Green Cove Springs and Tampa. His parents were George R. Davis, b. Jan 1857, Florida, and Gertrude M. Davis, born Sept 1867, Cuba. (Gertrude's father was from Scotland and her mother from New York). George was an engineer on a steamer. David had 2 younger brothers, Charles E. Davis born around 1890 and Milton H. Davis born around 1893.David's family moved to Tampa in 1895, where he attended school and held a number of different jobs. As a boy he carried newspapers for Knight & Wall Co., until 1905 when he went to Central America to work as a real estate salesman. After the canal opened he worked in Georgia and Texas, finally settling in Jacksonville in 1915. That same year, in Jacksonville, he married Marjorie H. Merritt. The young couple moved to Miami in 1920, where Davis began to sell real estate. He became quite adept, developing a number of subdivisions in the Buena Vista section of the city. He made a considerable fortune in Miami, but lost his wife in 1922, shortly after giving birth to their second child. Davis moved back to Tampa in 1924 and began work on the largest development on Florida's west coast. That development, Davis Islands, made him nationally famous. He followed up Davis Islands with Davis Shores, a subdivision in St. Augustine that Davis envisioned as being twice the size of Davis Islands. The Florida land boom collapsed before Davis could complete Davis Shores.

|

|

|

|

Rodney Kite Powell writes: "Florida

real estate in the mid-1920s seemed like a sure investment. With very

little money down, one could purchase a great deal of land, then turn

around and sell it for a profit without ever making a mortgage payment.

This type of land speculation drove the land boom, but it was about to run

out of gas. In 1926, there were over 850 companies and individuals listed

in the Tampa City Directory under its various real estate listings. The

land boom was still alive, but economic signposts of 1926 began to suggest

a turn in another direction. Tampa native D.P. Davis was a developer who

has prospered in the Miami boom. His vision was to convert the mudflats

and three small islands near the mouth of the Hillsborough River into an

idyllic island community. The Bayshore Boulevard neighbors, however,

sought to squelch Davis’ plan by claiming that the city could not

legally sell the submerged bottomlands. Among other reasons, they didn’t

want their view of the bay obstructed. In the early days of 1924, David

P. Davis began the lengthy task of assembling property for his Davis

Islands development." |

| "The first step centered on land acquisition and a contract with the city of Tampa that would sell him Little Grassy Island plus its share in Big Grassy Island. Read about the details of the opposition. He was able to purchase the property for $350,000. He also needed to receive permission to fill in the surrounding submerged lands. The lawsuit eventually went all the way to the Florida Supreme Court on appeal. The victory for Davis set into motion his ambitious plans: 834 acres, 11 ˝ miles of water frontage with seawalls and 27 miles of winding streets. The streets were to be named for bodies of water in somewhat alphabetical order starting at the north end of the island. Davis planned a resort community with three luxury hotels, a nine-hole golf course, airport and public swimming pool." | |

|

Little Grassy Island and Big Grassy Island, also known as Depot Key, Big Island and Rabbit Island The islands at that time were mosquito infested mangrove and marsh grass surrounded by mud flats. The original 121 acres were valued at about $1 an acre in the late 1800's when they were purchased from the State by several Tampa land speculators. At the right edge you can see Seddon Island, which became Harbour Island in 1984. Photo from the Burgert Bros. collection at the Tampa-Hillsborough County Public Library. |

|

|

|

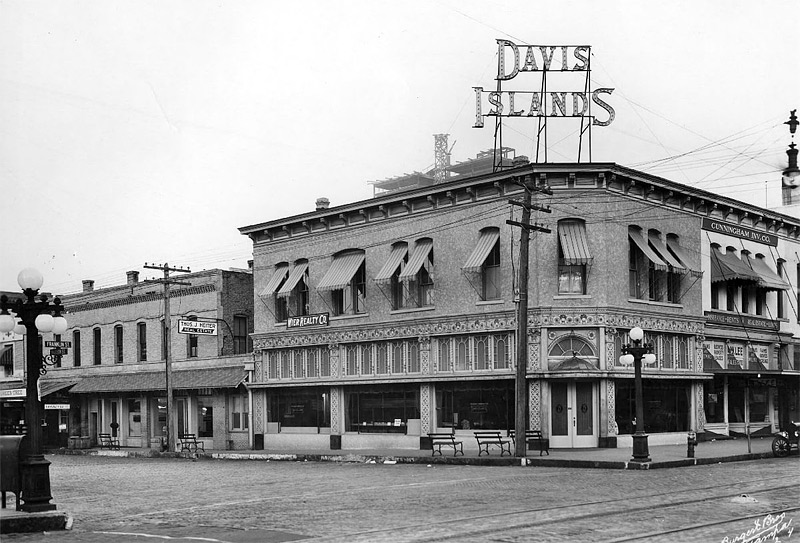

Photo from the Burgert Bros. collection at the University of South Florida Digital Collection.

The Davis Properties office in 1925, located at 502 N. Franklin Street When Davis announced details of his plan to build "Florida's Supreme $30,000,000 Development," the response from prospective buyers was overwhelming. Davis used the experience he gained in Miami and applied it well to the new Tampa venture. He opened a sales office in a very prominent downtown location, 502 North Franklin Street. One of the legends of the time relates that Davis chose this site because it previously housed Drawdy's Corner, a store whose windows he wantonly stared into at the candy displys as a boy. |

|

Rodney Kite Powell writes: The sales office was awash in plans,

schematics and propaganda detailing the future look, feel and functions

of Davis Islands. A forty-foot by twenty-foot three dimensional

model of the project, designed and constructed by noted artist Harry

Bierce and his staff, filled the center of the office. The model, like

most everything else Davis did, was billed as the world's largest.

The Davis Islands development would encompass three separate islands and

would be a city within itself, created for the new America booming all

around. Built with both the automobile and pedestrian in mind, Davis

Islands would have wide, curving streets, and the main thoroughfare,

Davis Boulevard, would have roomy sidewalks running along both sides.

Landscape design responsibilities were given to Frank Button, a widely

respected and nationally recognized landscape architect.

The Davis Properties, Inc. sales office site was selected at the northwest corner of Franklin and Madison Streets. It had been occupied by the Drawdy Grocery Store for thirty-seven years but, given a good price, Drawdy was pleased to move the grocery store to a new location at Swann and Delaware. Davis planned to spend nearly ten thousand dollars changing the former grocery store into the finest real estate office in the South complete with large plate glass windows facing Franklin Street.

By November, 1926, this building became the Bel-mar property sales office of the Lloyd Skinner Development Corporation.

|

|

|

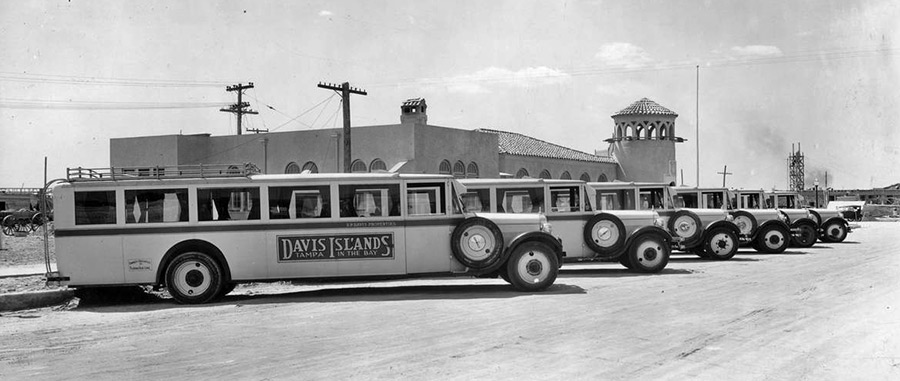

Rodney Kite Powell writes: Everything Davis did in the summer of 1924 led up to his ultimate goal--the opening of land sales on Davis Islands. Davis spent lavishly on elaborate brochures, a fleet of buses and vast improvements, costing an estimated $10,000, to the Franklin Street sales office. With the final design of the islands complete, maps were created showing lot locations.

|

|

Davis divided the

development into 8 sections, six of which carried a name describing a

particular feature or its proximity to nearby landmarks. The Hyde Park

Section, at the northern end of the islands nearest to Hyde Park, the Bay

Circle Section, just southwest of the Hyde Park Section, named for its

waterfront lots and circular street pattern, the South Park Section, at

the southern end of Marjorie Park, the Hotel Section, so named for the

Davis Arms Hotel, which was never built, the Yacht Club Section, named for

the Yacht Club which, too, was not built, and the Country Club Section,

including five of the nine holes of the Davis Islands Golf Course and its

clubhouse. The southern end of the islands, though platted, did not carry

section names. Land sales, Davis decided, would go one section at a time. |

|

Rodney Kite Powell writes: In order to build his islands, Davis hired the 4 largest dredges available. The dredges soon ran 24 hours a day in order to complete the ambitious project. Davis needed to dredge 89 million cubic feet of sand from the bay. As dredging continued, the lots went on sale. Prospective buyers waited in long lines and the streets near the sales office were jammed with congested traffic. When the doors opened pandemonium ensued. Within the first 3 hours, all of the initial lots offered (306) were sold. The Tampa Tribune said that Mr. Davis “was literally showered with checks.” The $1,683,582 in sales was a world’s record for the sale of lots in a new subdivision. Photo from the Burgert Bros. collection at the Tampa-Hillsborough County Public Library. |

|

|

Davis created a carnival-like

atmosphere around his land sales, sponsoring boat races around the

Islands and along Bayshore Boulevard, airplane exhibitions with stunt

flyers, sports celebrities such as Olympic swimmer Helen Wainwright, who

swam around Davis Islands, plus tennis tournaments and golf lessons from

tour professionals Bobby Cruickshank and Johnny Farrell. The

fervor created by the first land sale carried into the next, when lots

in the Bay Circle Section went on the market on October 13, 1924. This

scenario repeated itself each time lots came on the open market. As in

Miami, Davis made sure to mention that many lots were purchased by home

folks who knew a good investment when they saw it. Realizing the need to

not flood that lucrative market, Davis spaced out the sales from days to

weeks apart, allowing the property values to increase each time.

Resales between individual buyers contributed to the frenzy of Florida's

land boom, and the action surrounding Davis Islands proved no exception.

Davis understood the importance of resales, both in how they maintained

interest in his property and how they enhanced his own bottom line. He

could raise the price on his own lots and, in theory, could also

participate in the resale market himself. After October 15, 1925,

resales were the only method of acquiring land on Davis Islands. |

|

While Davis promised the city an expensive permanent bridge to the development, he needed a quick and cheap temporary bridge just to get men, machines, mules and materials to the site. The temporary bridge opened November 8, 1924, thirty-five days after land sales began for Davis Islands. The following day, the Morning Tribune featured a photograph of Davis' business partner, A. Y. Milam, with two-year-old David P. Davis, Jr. in his arms, the first people to drive onto Davis Islands. Within days after completion of the temporary bridge, photographers and sightseers joined the construction crews on the ever-growing property. View from the south showing

unfinished dredge fill.

|

|

|

Rodney Kite Powell writes: After his wife's 1922 death, Davis

began to indulge in the excesses that marked the Jazz Age. Defying

prohibition, a Davis hallmark, was a core tenet of the era. He also

began seeing a woman named Lucille Zehring, one of movie producer

Mack

Sennett's Bathing Beauties. Another product of the free-wheeling

Twenties, Zehring would play a very pivotal role in Davis's future.

|

|

Mack Sennett Bathing Beauties, 1922 |

|

D. P. Davis and his much publicized marriage to Elizabeth Nelson Rodney Kite Powell writes: Blessed in early 1925 with success, cash and an extraordinary ego, Davis cast his determination in a more personal direction. One of the enduring stories regarding Davis at this time centers on what seemed an absurd assertion, that he would marry the next Queen of Gasparilla, who had yet to be named. Davis once again, the legend goes, showed he could accomplish anything he truly desired, marrying twenty-two-year-old Elizabeth Nelson, Queen Gasparilla XVII, on October, 10, 1925. Davis, who would soon turn 40, allegedly made this claim over a glass of champagne early in 1925. The naming of the court of Gasparilla is a secret, but it is decided in advance of the Coronation Ball. Davis had a number of connections within the Krewe, and it is quite likely that he knew Nelson would be elected queen. On October 10, 1925, Davis and Nelson were wed at the “Presbyterian manse” in Clearwater (possibly Peace Memorial Presbyterian Church on Fort Harrison Avenue and Pierce Street). The only people to attend the hastily planned wedding were Nelson’s sister, Mrs. C. G. Rorebeck and Ray Schindler, one of Davis’ business associates. Later, Davis and Nelson divorced and remarried in the span of eight weeks. Rumor and innuendo flew as to the reasons why the couple's relationship was particularly stormy.

|

|

|

|

Rodney Kite Powell writes: The year 1926 began with news

of slow real estate sales, a condition which did not worry Davis or

most other Florida developers. But as the year progressed, so did

Davis’ problems. Instead of receiving an expected four million dollars

in second payments on Davis Islands property, only $30,000 in

mortgages payments arrived. Both Davis Islands and Davis Shores (his

St. Augustine development) had sold out by this time, and re-sales

were moving slowly. Davis had a serious cash flow problem. Davis was

not alone in his fall from realty grace.

|

The entire Florida real estate market began a steady decline in 1926 and outside observers were quick to point that out. The New York Times reported a “lull” in the Florida market in February. By July, the Nation claimed that the real estate business in Florida had collapsed. “The world's greatest poker game, played with building lots instead of chips, is over. And the players are now ... paying up.” Davis Shores in St. Augustine continued to draw away Davis’ available resources, resulting in slower construction on Davis Islands. An overall shortage of building materials made matters worse.

W.R. Kenan Jr.

and

1925

advertisement for Davis Shores |

|

Above:

Old Drawdy's Corner in Nov. 1926. Notice the Tampa Tribune

building in the background has been completed. Photo at left shows

the Davis land office in the center, with the Tribune building at upper

right, 1925.

Above:

Old Drawdy's Corner in Nov. 1926. Notice the Tampa Tribune

building in the background has been completed. Photo at left shows

the Davis land office in the center, with the Tribune building at upper

right, 1925.