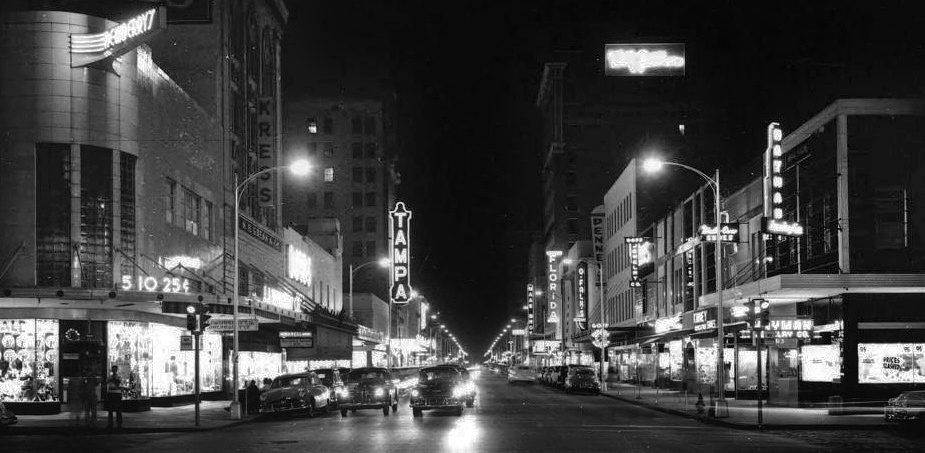

Nighttime scene on Franklin Street, 1940s -

Robertson

& Fresh / University of South Florida Digital Collections

L to R: J.J.

Newberry's, S.H. Kress, Butler's Shoes, F.W. Woolworth,

Tampa Theater, Maas

Bros, Wolf Bros, Florida Theatre, O. Falk's, J.C. Penney's,

Goff Jewelry, Kinney

Shoes, Walkover Shoes, Hayman Jewelry

|

THE GREAT DEPRESSION – 1930s Like so many cities in the United States, Tampa in the 1940s was a revival compared to the 1930s. Wednesday, July 17, 1929, was a dark day in Tampa’s history. On that morning, one of the city’s largest banks, Citizens Bank & Trust Company, failed to open its doors for business. As did five smaller banks affiliated with the Citizens: the Bank of Ybor City, the Franklin Bank, the Citizens Nebraska Avenue Bank, the Lafayette Bank and the American State Bank of Tampa. This was attributed to a wild rumor that had swept through Ybor City on Monday, two days before—a rumor that Tampa banks were insolvent. A lector in one of the cigar factories had read reports of bank failures in other cities and numerous workers became fearful of their money in local banks. They stormed out of the factory and started a run on the Bank of Ybor City. Reports of the run spread like wildfire, causing a silent run on the Citizens Bank downtown. At the end of the next day, Tuesday, July 16, the Citizens Bank closed after having paid out $1,120,000 in cash, and the run continued. Bank officials conferred with state bank examiners and for a while, they believed the banks could be saved, but by daylight they came to realize there was not enough cash in their vaults to weather the storm if it continued, as it most surely would. To protect their deposits, they agreed that Citizens, and their affiliates, would not reopen that day for business. The Tampa Times didn’t get out an extra to tell about the bank closings, but word of the disaster soon reached the whole city, leaving people stunned. Businesses that had accounts in the closed banks, along with their life savings, had been dealt a staggering blow. Fear fed on fear, and runs were started on the 3 banks that were still open—the First National, the Exchange Bank, and the First Savings & Trust Company. Before their banks were opened, they made arrangements to obtain a million dollars in cash from Jacksonville, on orders from the Federal Reserve Bank in Atlanta. The cash arrived by chartered plane at Drew Field at noon, piloted by Laurie Yonge. It was met by a police squad and the money was rushed to the banks. That night, $4,000,000 more in cash was brought in by express. Not all was needed, and by Thursday afternoon, the last fear-stricken depositor had been paid, and the runs were ended. The collapse of Citizens and its affiliates cost the people of Tampa nearly $10 million. The crash had repercussions throughout southwest Florida. Affiliated banks in other cities were forced to close: the Bank of Plant City, the Bradenton Bank & Trust, the First Bank & Trust of Sarasota, and the First Bank & Trust of Fort Meade. Depositors in all those banks lost heavily. Tampa’s hopes of recovering quickly were shattered by the devastating stock market crash of October, 1929. Before the year ended, stock losses throughout the nation totaled 15 billion dollars. The Great Depression had started, and with each passing month, the nation’s paralysis became more severe. Thousands of winter visitors who had been coming to Florida for years, remained in their northern homes. Those who did come spent more cautiously. Merchants in every city were hard hit. Hundreds did not take in enough to pay their rent and were forced to lay off employees they had for years. Construction activity practically ceased. Coming so soon after the Florida crash, the national depression caused infinite hardship. Being the commercial center of southwest Florida, a section heavily dependent on tourist business, Tampa suffered acutely. Many of its wholesale concerns went bankrupt. Even the cigar industry suffered when millions of cigar smokers quit smoking or turned to pipes or cigarettes. The cigar factories were forced to lay off thousands of workers, causing Tampa’s worst unemployment problem in its history. Relief agencies were swamped. For the minority of those who had money, the Great Depression was not much of a hardship. Living costs were extremely low. Prices advertised in local newspapers show that in Nov. of 1932, per pound prices were: pure pork sausage was 10 cents; best grade sirloin steak, 15c; best grade ham, 18c; six large cans of pork and beans, 25c, 10 lbs. of potatoes, 11c; young roasting hens, 18c,; six tall cans of evaporated milk, 24c; three tall cans of salmon, 25c, and so on. Living was cheap for those with money, but thousands had no money. The first federal relief funds were a mere dribble, coming to Tampa in the spring of 1932. Other dribbles followed, basically keeping people from starving, but that was about all. Under FERA rules, workers received 17 cents an hour for a maximum of 140 hours per month, or $23.80. Only one person in a family could take a relief job. In the spring of 1934, a total of 16,488 persons in Hillsborough County were certified for relief, and the WPA came in to existence. WPA headquarters were set up in Tampa in the Wallace Stovall building. In 1933, when Tampa began planning projects to provide work for the unemployed with federal assistance, Drew Field came into the picture. The city's lease on the 160-acre tract had expired, but the city finally succeeded after much squabbling, in buying it for $11,654, the amount at which it was appraised by the Tampa Real Estate Board. This purchase was made on Feb. 10, 1934. Work on improving the field was started as a CWA project 10 days later, $31,000 being allotted for it by the government. Another allotment of $46,000 was made by WPA on Aug. 7, 1935. Thereafter, development progressed steadily, allotments being made from time to time by the Civil Aeronautics Association. Three 7,000 foot long asphalt runways were built, lights ere installed, and other improvements made. By 1938, Drew Field was rated as one of the best in Florida. See a more detailed history and photos of Drew Field A major WPA project for Tampa, approved on August 2, 1935, allotted $105,343, was for the development of a municipal airport on Davis Islands, land for which was obtained from the Island Investment Company in a tax settlement deal. The airport was named the Peter O. Knight Airport in recognition of the help given by Knight in arranging the land transfer; also because he was one of the town’s leading citizens. Workers started on August 7th and on August 16th, the first payroll came with 234 men receiving a total of $1,470. Work on Peter O. Knight Airport cost $462,264 before it was completed. This included the cost of dredging and grading, building runways and constructing the terminal building, hangars and administration buildings. From then on, WPA rolls climbed rapidly. By end of August, 1,071 men were placed at work on a mosquito and malarial control project for which $403,560 was allotted. There were hundreds of projects, large and small; for women as well as for men, for skilled professional people as well as unskilled day laborers. The most outstanding project was the work done on Bayshore Blvd., the first allotment for which was made on Nov. 4, 1935, amounting to $248,689. During the next 3 years, new seawalls were constructed the entire length of the boulevard and new, much wider pavements laid. Also, the missing link between the Platt Street Bridge and Magnolia Street was opened and completed. Altogether, the work on Bayshore cost $1.2 million. The costly project had been made necessary largely due to the old seawall, built for the city and county less than 10 years earlier, had been shoddily constructed and had gone to pieces in many places. Nearly a million dollars was spent in various other ways on the land acquired in 1905 from the estate of Henry B. Plant. Repairs to the Tampa Bay Hotel cost $138,000; another $186,000 went for the development of Plant Park; $129,000 for grandstands and bleachers at Plant Field, and $465,000 for buildings and other improvements at the fairgrounds. Projects at the fairgrounds were sponsored by the South Florida Fair Association; the others were sponsored by the city. A total of $362,000 was spent for the construction of the armory of the 116th Field Artillery, the first battalion of which had been mustered in at the Tampa Bay Casino on Dec. 5, 1921. During the 1920s, ten frame buildings and a boxing arena had been built for the artillerymen and in 1934, two red brick buildings had been built as CWA projects at a cost of $30,000 each. In August of 1938, a WPA allotment of $271,000 was made for the main armory building and another allotment of $91,000 followed on Dec. 23, 1940. After the entrance of the U.S. into World War II, the armory was named Fort Homer W. Hesterly in honor of Colonel Hesterly, one of the organizers of the artillery unit which then was in active service. During the war, the armory served as headquarters for the 3rd Air force. By the end of October, 1935, WPA rolls totaled 3,675. This increased to 5,032 by Jan. 1, 1939. At that time, 2,196 more were eligible for jobs but no more jobs were available. Thereafter, the number of WPA workers declined rapidly—World War II was bringing prosperity back to the nation. Up to April 9, 1941, a total of about $19,800,000 was spent on WPA projects in Hillsborough County, mostly in Tampa. Of that amount, almost $16 million came from the Federal government and almost $4 million from sponsors in the form of money, materials or land. More than three-fourths of the $19.8 million total was spent on labor. |

One tradition that the tabaqueros (cigar makers) brought with them from cigar factories in Cuba was that of El Lector (The Reader). Because the job of rolling cigar after cigar could become monotonous, the workers wanted something to occupy and stimulate the mind. Thus arose the tradition of "lectors", who sat perched on an elevated platform in the cigar factory, reading to the workers. Typically, the lector would start the day reading local Spanish newspapers and some fiction, such as a romance or adventure novel. Since most residents of Ybor were very interested in politics, the lector would then usually move on to political treatises or writings about the current events in Cuba or Spain or other countries. In the afternoon, the selection was often a literary novel, such as Don Quixote or other works of classic literature. (In Nilo Cruz's Pulitzer Prize-winning play Anna in the Tropics set in Ybor City, Tolstoy's Anna Karenina is read.) Because of the lector system, even cigar workers who could not read were exposed to classic literature and were conversant on political philosophy and current events both in Ybor City and around the world. Lectors were well respected and often highly educated. Most could look at text written in English or Italian and read it aloud in Spanish, the language of the factories. The lectors were hired and fired by the tabaqueros, not the factory owners. Their salary was paid directly by the workers through a small deduction from everyone’s weekly earnings. Despite the cost, the tabaqueros enthusiastically sustained the lector tradition. Most factory owners were less supportive. They felt that the lectors stirred up their workforce by fostering “radical ideas”. News of labor conditions or problems in other locations, especially, led to worker walkouts and protests on many occasions. More than one owner tried to ban lectors from his factory floor, leading to bitter strikes as his employees fought for their “right” to have a lector. The lectors would remain fixtures in Tampa’s cigar factories until 1921, when several owners negotiated the removal of the lectors as part of an agreement to end a labor strike. At the end of a particularly bitter strike in 1931, workers in all Ybor City and West Tampa cigar factories were forced to agree to the removal of lectors. Some of the lectors continued to speak to the cigar workers in other ways. Victoriano Manteiga, for example, founded La Gaceta, a tri-lingual newspaper which is still published by his grandson in Tampa. Some took other jobs, becoming teachers or regular tabaqueros. Some went to Cuba to seek lector positions in factories which still allowed the practice. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The University of Tampa,

formerly the Tampa Bay Hotel, with downtown in the background, 1937

Burgert

Bros. photo courtesy of USF

|

Tampa Gets a University Because of government help, Tampa received many worthwhile projects during the depression years. But one of the best obtainments, with perhaps the greatest long range possibilities, came entirely through the initiative of its own citizens, at very little cost—the University of Tampa. The idea of establishing a university in the city, first considered in the late 1920s, was stimulated by the depression. After the crash, many Tampa families which normally would have sent their children to colleges and universities in other cities, were no longer financially able to stand the expense. Deeply deploring the fact that Tampa’s youth was being denied educational opportunities, a group of leading citizens decided that something must be done, and quickly. After long discussion, they agreed that a university should be established here. Leaders in the movement were V. V. Sharpe, George B. Howell, S. E. Thomason and John B. Sutton. The first step to make the institution an actuality was taken on March 13, 1930, when the Tampa University was incorporated with several leading citizens as founders. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Having high hopes but no money, the incorporators were forced to wait for more than a year before they were able to carry out their plans, and even then they were unable to establish a university. The best they could do was to start a junior college. It opened on October 5, 1931, in the Hillsborough County High School, with 65 students. Classes were held five evenings a week, from 4pm to 9pm. The instructors were volunteers, receiving no pay for their services. Frederic H. Spaulding was president and Paul F. Strout, dean. Both were Harvard graduates with M.A. degrees. Attendance at the junior college doubled during the second year and the trustees realized that if the institution hoped to survive, it would have to obtain a building of their own. After mulling over various proposals for months, with many setbacks, they finally centered their attention on the old Tampa Bay Hotel, then standing vacant. The once magnificent hotel, purchased by the city from the estate of Henry B. Plant in 1905, had become a huge, red elephant with minarets. One leaseholder had followed another but no one made money until the Big Boom of the 1920s when the mammoth structure was filled with paying guests for the first time since the Spanish-American war days. During the boom, W. F. Adams, who held the lease, became so affluent that he spent $70,000 of his own money to renovate the run-down building. The city, which also was affluent, put in $187,000 more. Then came the crash, and the hotel stood almost empty all season. Adams lost heavily, and he continued to lose much more each winter thereafter. Finally, on August 22, 1932, he went bankrupt. City officials tried in vain to find someone else who would lease the hotel, but they had no success. So they listened attentively when the university advocates broached the subject of acquiring the building. On August 1, 1933, a lease was signed. The university would pay $1 a year for the hotel which had originally cost $3 million. Crews of relief workers were hastily assembled and work of converting the hotel into something that looked like an educational institution was immediately started. During the following month, more activity was seen around the hotel than had been seen since the gold-braided army officers departed for Cuba in 1898. By the middle of September, the conversion job had progressed enough to permit the opening of classes on the 18th, this time as a full-fledged college. Student enrollment totaled 350. President Spaulding was still in charge, but John Coulson had succeeded Strout as dean. The faculty was enlarged to make it possible to award the degrees of B.A., B.S., and B.S. in Business Administration. The infant university even boasted of having a football coach—Nash Higgins. Truly, the university had taken its place in the Florida sun. The university operated on a shoestring when the first classes started. The trustees had only $3,500 in their operating fund and there were no big donations in sight. Tuition fees were necessarily low and only by exercising the most rigid economies was the university able to weather that first year as a senior college. But it did, and its credits were validated by the University of Florida and the State Board of Education. Tampa University had come to stay.

|

|

|

|

|

The narrative for this

series of Tampa in the 1940s is primarily from Karl Grismer's |

|

Page1 | Page2 | Page3 | Page4 | Page5 | Page6 | Page7 | Page8 | Tampapix Home