|

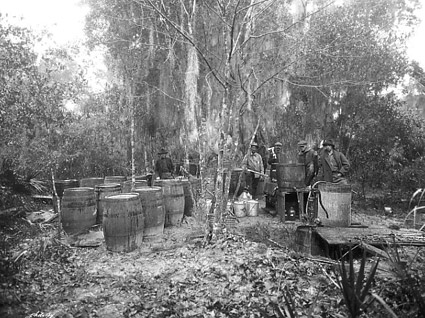

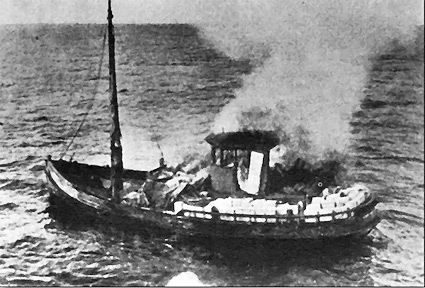

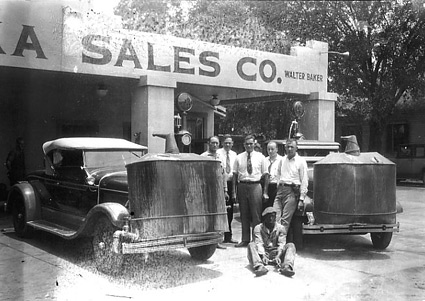

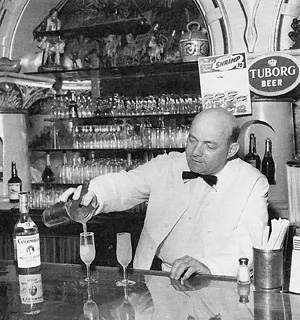

Prohibition Years For the 16 years that followed the 1919 Prohibition Act, widespread non-compliance of federal and state prohibition laws made Tampa one of the "wettest" spots in the United States. In fact, in 1930 there were reportedly 130 different retailers surreptitiously selling a wide variety of intoxicating beverages. In Tampa, prohibition was a miserable failure. Besides raising the price of liquor and lowering its quality, the "Noble Experiment" exacerbated Tampa's wide-open moral conditions, corrupted law enforcement and other public officials, and fostered the growth of an emerging criminal element. During the 1920s and early 1930s, Tampa received most of its illicit liquor from three sources: local bootleggers, rural moonshiners, and international smugglers. The art of moonshining was practiced long before the advent of Prohibition. For generations, federal tax collectors scoured the outskirts of Tampa looking for tax-evading moonshiners. Until 1920, the illegal production of alcohol was a small and relatively insignificant business. It was primarily produced for home consumption or sold to neighbors. With the passage of the 18th Amendment, however, the production of moonshine grew into a large, commercial enterprise in the rural districts of Hillsborough and other surrounding counties. Although the rural areas surrounding Tampa contained an untold number of stills, the "Daddy" of the early moonshiners was a colorful character named William Flynn. A cooper prior to the 18th Amendment, by 1920 he had an impressive three-still operation that supplied much of West Tampa. Unfortunately for local retailers, this moonshining entrepreneur soon experienced some bad luck. On October 14, 1920, federal agents raided his business and destroyed the stills. Within days, however, other opportunistic "shiners" filled the void created by Flynn’s arrest. The alcohol supplied by rural moonshiners was a cheap alternative to homemade wine or expensive liquor. Yet there was a potential risk for individuals who consumed this backwoods "shine." Every year during Prohibition poorly prepared moonshine killed or made seriously ill hundreds of customers. All too often small operators, with little knowledge of the distilling process, allowed poisonous leads and salts to seep into the mixture. Moonshine found a receptive market in Tampa’s more notorious speakeasies, but most people preferred high quality imported liquor. Because of its geographical location and numerous inlets and coves, Tampa became a haven for smugglers during the Prohibition era. For 16 years scores of "black ships" operated off the coast of Tampa Bay bringing in unlawful liquor. Skillful sea captains, financed by both legitimate business concerns and criminal organizations, risked possible arrest and the impounding of their vessels for high profit yields. The main source of Tampa’s liquor supply came from Cuba and especially the Bahamas. Few of these rumrunners and their bootlegging allies ever spent time in prison for violating federal and state prohibition statutes. Although the Tampa Daily Times and Tampa Tribune were filled with stories about spectacular liquor raids and well-publicized trials, the lucrative rum trade operated with impunity in Tampa. Public hostility to the Volstead Act, widespread community involvement in the smuggling business, and most importantly, blatantly corrupt city and county officials, made Tampa one of the "leakiest" cities in the United States. The official police records during the prohibition era were deceptive. First, many of those arrested were habitual offenders. The prospect of arrest did not intimidate the city’s liquor violators because municipal judges rarely imposed more than token fines. Liquor dealers were fined on a regular basis and many were arrested twice or more within a week’s time. According to one policeman, "bootleggers made no bones of their business, smiled when arrested, paid up immediately, and continued to defy authorities.” To many bootleggers, getting arrested was merely a slight inconvenience and a minor occupational hazard. Secondly, many of those arrested selling alcohol gave false identities or distorted their names beyond recognition. Finally, the corrupt elements in the department often warned the city's underworld of impending raids. In order to appease the community's prohibitionists, police periodically swept through Ybor City and Tampa and temporarily closed several speakeasies and coffee houses. Forewarned, the establishments scheduled to be raided secreted their high quality liquor and left only a case or two of cheap moonshine in plain view for Tampa's vice squad detectives to confiscate. Following a perfunctory hearing before a sympathetic municipal magistrate, victims of these rehearsed raids usually resumed their illicit businesses within hours.

The local bootleggers were predominantly Italian immigrants who engaged in the trade to supplement their meager salaries. According to Gary Mormino and George Pozzetta in their book, The Immigrant World of Ybor City,

Throughout the Treasure City enterprising Italians built crude but efficient stills that produced a variety of potent potables. This cottage industry that employed perhaps as many as 50 percent of Ybor City's families, supplied an eager and appreciative market. In fact, scores of restaurants, coffee houses, and speakeasies served as outlets for this local "alky cooked" liquor. Prohibition brought tremendous sums of money into Tampa's Italian community, raising the socio-economic status of those engaged in the illegal trade. The "Noble Experiment" was also important because it brought Italian-Americans into Tampa's criminal underworld. Prior to the passage of the Eighteenth Amendment, organized crime was the near-exclusive domain of the city's Cubans and Spaniards. They controlled all major forms of vice, including the lucrative bolita industry--the Cuban numbers. Brought to Ybor City in the 1880s, this popular form of gambling began as a small sideline business found in Latin saloons. It soon became the single largest illegal money-making enterprise in Tampa’s history. |

The use of some photos on this page does not imply that the subject of the

scene

|

||||||||||||

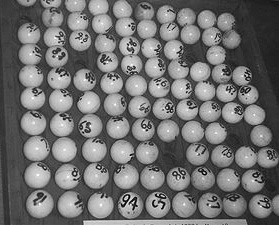

Bolita Throwing By 1900, bolita had become a ritual in Tampa. Every night crowds of gamblers and curious onlookers gathered at one of the lavishly decorated sporting parlors to watch the daily "throwing." The lottery commenced when 100 ivory balls with bold black numbers were exhibited on a large table. This was done to ensure that none of the balls was missing, thus increasing the odds for the operators. After a brief inspection, all 100 balls were placed in a velvet sack, which was tightly tied. At this point the "throwing" began as the sack went from person to person. Finally the bag was grabbed by a "catcher," who held one ball securely, still within the bag, in his closed fist. The operator then tied a string around the sack, just above the imprisoned ball. He then cut the bag above the string and allowed the winning number to drop in his hand.

|

|||||||||||||

|

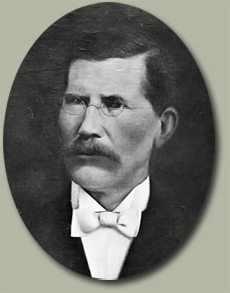

Charlie Wall

As the Cuban numbers became increasingly profitable, many gambling brokers expanded their operations. In fact, there were few places in Tampa where one could not purchase a bolita ticket. Along with this expansion also came consolidation. By the 1920s, the bolita trade was virtually monopolized by a man named Charles Wall. This gambling czar, with his brilliant organizational skills and powerful political connections, became the undisputed master of Tampa’s bolita empire and controlled it for nearly three decades.

Following a brief stay in a juvenile detention center, Wall was sent to the Bingham Military School in North Carolina. His scholarly career, however, was short-lived; he was caught in a local bawdy house and promptly expelled from the academy. Returning to Tampa, the restless misanthrope gravitated toward the city’s budding gambling industry. Beginning as a courier, he soon became a bookie and planned to expand his power further. Wall’s preeminence in the city’s gambling fraternity was firmly established in the 1890s when he seized control of the bolita rackets, which had previously been run from the island of Cuba. It is highly probable that Wall was encouraged and even financed in his takeover attempt by Tampa’s elite business community, which did not like the idea that gambling revenues were leaving the city. Many wanted the money to remain in the Treasure City where it could be used to encourage new industries and other commercial ventures. Despite a morphine addiction, which he overcame, Wall rose to become Tampa’s gambling czar. He maintained this position for over three decades by controlling the city’s "hot" voting precincts. When Wall could not purchase the necessary votes to win an election, he simply stuffed the ballot boxes. At the height of his power, few Tampa politicians won their elections without first securing Wall’s blessing. In fact, "Many observers staunchly believed that during these decades (when Wall ruled the city’s political structure) there was not one single honest election in Tampa/Hillsborough County." Wall also retained his title as Bolita King by eliminating his potential opponents. At least six rivals met violent deaths attempting to dislodge the city’s powerful vice lord. Charlie Wall was a fascinating anomaly. A cold-blooded killer who did not hesitate to order the execution of anyone encroaching on his territory, Wall was also described as a "polite and soft-spoken" individual who frequently donated large sums of money to churches and assisted a number of working-class families facing economic hard-times. His most legendary philanthropic act occurred in 1910. In the midst of a brutal strike, Tampa’s Bolita King provided food for 900 cigarworkers and their families. Few Latins forgot Wall’s generosity. A director of the Hillsborough County Crime Commission had said of Wall that the "facade of courtly manner that sheltered the man" was a symbol of Tampa's coarse lawlessness. On March 9, 1939, Wall's closest known associate, Tito Rubio, was cut down by gangland lead. It was during a grand jury hearing that Wall was recognized officially as the "brains" and elder statesman of the lottery rackets. In spite of his professed link with the rackets, his only close call with justice in his 75 year record was in 1931 when a Federal court found Wall guilty of a narcotics violation and sentenced him to two years in prison. The conviction was reversed by the U.S. Court of Appeals. Regardless of Wall’s lofty status in Tampa’s Latin community, by the early 1930s his undisputed reign over the bolita trade was increasingly challenged by Italian gangsters. During the Prohibition era, Italians engaged in the illicit liquor business earned a considerable amount of money and wielded growing power in the city. They were restless and no longer content with their bootlegging profits. Some hungered to crack the Wall-Cuban bolita monopoly, and were willing to utilize violence to achieve their goals. The first sign of destabilization in Tampa’s gambling community occurred on June 9, 1930. While standing in front of his garage door, Wall was ambushed by assailants in a speeding automobile. The Bolita King was not seriously injured (he received a minor shoulder wound), but the incident signaled the beginning of a bloody gang war between the Old Guard mobsters and upstart Italian gangsters. Not all Italian bootleggers wanted access to Tampa’s bolita rackets; many were content to operate their small cottage industries. The insatiable demand for liquor insured little rivalry and a high profit yield. The only competition the city’s bootleggers encountered was found in the countryside. Moonshine was not only sold in rural communities, but also found in Tampa’s poor sections. Organized Crime in the 30s and 40s In May of 1951, the Kefauver Committee released their Interim Report #3 on its findings on organized crime in Tampa. The committee hearings in Tampa were conducted against a backdrop of gangland violence and vengeance pointed up by a sordid record of more than a dozen racket killings and six attempted assassinations in less than two decades. Through this bloody history runs the obscure but sinister shadow of Mafia operations, with its accompanying links between the criminal overlords of Tampa and their counterparts in other sections of the country. The committee could not make an adequate investigation of the Mafia background of these murders because all suspected Mafia adherents vanished from their homes and usual haunts when it became known that the committee intended to investigate their activities. Months after the committee's visit to Tampa, these men continued to evade process. It was freely stated in the particular circles in which they operated that they intended to remain in secret refuges until the life of this committee expired. In Tampa, as in other cities visited by the committee, there was found the same dismal pattern of corruption of public officials by entrenched gambling interests which the committee found in other cities. These interests resorted to the customary policy of outright bribery and channeled substantial amounts of money into political campaigns, for the control they had over law-enforcement officers. Bolita Thrives in Tampa The main source of revenue for the gambling fraternity in Tampa was a variation of the numbers racket known as Bolita. It was similar to the numbers racket in other parts of the country but with some variation in the systems of drawing the numbers. The system of distributing the bolita business among the existing bolita bankers was different from the methods used in other cities in arriving at an equitable division of the spoils. Elsewhere, those engaged in the numbers racket were inclined to establish territorial limitations within which numbers banks could operate. In Tampa the bolita operators were free to operate anywhere within the territory. However, each banker received an assignment of men who were charged with the obligation of picking up the day's play and these men in turn were furnished with the names of specific places where bolita was sold. Thus the operations of any particular bank were limited to a specific number of selling points and an adequate number of pick-up men to cover these points, regardless of geographical location. Apparently bolita operations did not run smoothly in Tampa. The last two gangland killings involved leading principals in the operation of the bolita racket. Jimmy Velasco was killed on December 12, 1948, and Jimmy Lumia on June 5, 1950. No one was convicted of the other Tampa gangland slayings, with one exception in 1932.

Admittedly, the participation of the Mafia in Tampa's series of murders and attempted assassinations was predicated on inferences. As is well known, intimidation and threats of retaliation served to silence witnesses of homicides traceable to this organization. However, an analysis of the existing information produced some enlightening facts that reveal an easily recognizable pattern. Connections with other cities were clearly shown by the record. One of the fugitives from the committee's process was Santo Trafficante, Sr., reputed Mafia leader in Tampa for more than 20 years. A search of the effects of Jack Dragna, one of the alleged Mafia leaders on the Pacific coast, yielded the telephone number of Trafficante and also that of the late Jimmy Lumia. The lamentable state of the files of Tampa killings, kept by the Tampa Police Department, was emphasized by the testimony of Chief of Police M. C. Beasley. In fairness to Chief Beasley, it must be pointed out that he had occupied his position only 5 months prior to the time he was called to testify before the committee and the responsibility for the condition of the department's records was not attributable to him. Requested to produce the files concerning the gangland killings in which the committee was interested, Chief Beasley was forced to admit that in many of the cases there were no files at all, and that in most of the remainder the information was extremely sparse. Whether the disappearance of the records was a matter of accident, carelessness, or design was not readily discernible. Police Files on Murders Missing One of the missing files dealt with a character known as George "Saturday" Zarate, twice made a target of gangland vengeance. On November 10, 1936, he was shot at 8th Avenue and 14th Street at the El Dorado casino by two gunmen in a car, firing sawed-off shotguns. He was also attacked by gunfire on another occasion at his home in the 2100 block of Nebraska Avenue. Zarate's career was marked by an arrest in New York as a suspect in dope trafficking with Charles "Lucky" Luciano. The only murder conviction in Tampa during the 30s and 40s was that involving Zarate's brother, Mario, who was given a life sentence for the killing of Armando Valdez, a wholesale produce dealer, in 1932. Oddly enough, the records in the Valdez slaying also were missing from the police department files. Another significant tie-up with the Mafia appeared in the murder of Joe Vaglichi, alias Joe Vaglichio. He died in a hail of shots poured from shotguns wielded by assassins in a passing car outside his sandwich stand early on the morning of July 29, 1937. There were no arrests and Vaglichi's past history which caused police at the time to credit his death to Mafia internal conflict. Vaglichi was one of 23 Italian gangsters rounded up by the Cleveland Police Department in a hotel in that city in December 1928 after the Cleveland police had been tipped off that Mafia leaders were congregating there for a meeting. Thirteen revolvers were found among the 23 prisoners, who also included Ignazio Italiano of Tampa. Vaglichi also had been tabbed by authorities in subsequent years as a killer in the pay of the Mafia for jobs in New York, Chicago, Detroit, and New York, although never convicted. He also was reported to have had a brother in the Chicago rackets who had been a bodyguard for Al Capone. The Tampa police file on the Vaglichi slaying was limited to a newspaper report of the murder, Vaglichi's criminal record, and a statement about the killing. There were no investigative reports of any kind. As the mafia grew in stature in Tampa a war broke out between the various gambling factions for control of the bolita and narcotics rackets. At this time there was no true boss in Tampa. Some early powers were the Diecidue family, Augustine Lazzara, the Velasco brothers, the Trafficantes, Salvatore Italiano, and Ignacio Antinori. Sal Italiano was the leader of the gambling rackets, while Antinori, along with his sons Paul and Joe controlled narcotics. Ignacio Antinori eventually fell out of favor with some Chicago gangsters after selling them a bad batch of narcotics and was gunned down in Tampa. Over 25 killings took place from 1930 until 1959. This has come to be known in Tampa as the "Era Of Blood". Among those killed were Joe Vaglica (July 10, 1937), Mario Perla (Oct. 12, 1939) and Jimmy Velasco (Dec. 12, 1948). Indications of a New Orleans connection with the Tampa killings were found in the circumstances surrounding the murder of Ignacio Antinori, slain by a masked gunman in a suburban tavern. On October 22, 1940, Ignacio Antinori was sipping coffee at the Palm Garden Inn in Tampa with a friend and a young female companion. Suddenly, a gunman appeared at the window and fired two shotgun blasts at Antinori. The murder weapon was traced to a New Orleans store where it had been purchased by a man who gave the obviously false name of John Adams. The date of the purchase was October 7, 1939, which was only 5 days before the murder of Mario Perla. Whether the same gun figured in both murders was not made clear. Antinori had been at odds with the syndicate controlling Tampa gambling for 3 years before he was slain.

In the late 40's Sal Italiano left for Italy, leaving James Lumia in charge. Lumia is credited by the FBI as the first true Mafia boss in Tampa. Lumia's reign was short-lived as he was killed by a shotgun blast on June 5, 1950. He was succeeded by Santo Trafficante Sr. Trafficante ruled until his death in August of 1954 from stomach cancer. He was succeeded by his son, Santo Jr.

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

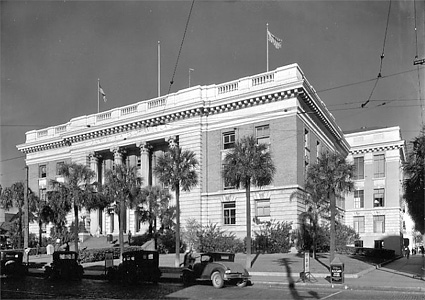

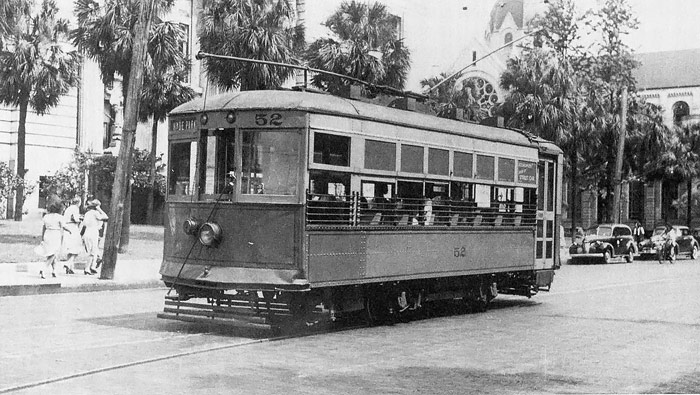

A streetcar in front of the Post

Office at the Federal Court building, 611 N. Florida Avenue. (Sacred Heart

Catholic church at upper right.) |

|||||||||||||

|

Nobody Goes to Jail for Gambling Law-enforcement officials in Tampa were unable to cope with violence stemming from organized crime. They were also unable to enforce the gambling laws of the State. In the city of Tampa and Hillsborough County for the period of January 1 to September 1, 1950, only 96 arrests for gambling violations were made and not one of those apprehended landed in jail. Forty-five of those arrested forfeited bonds and the charges against 43 others were dismissed. Only six defendants were fined and there were two cases pending as of September 1, 1950. Much of the violence in Tampa arose out of the failure on the part of the police department to enforce the gambling laws. Antinori, Lumia, and Velasco, three victims of gangland killings, all had at one time or another before their deaths held the tenuous title of king of Tampa gambling. The close alliance between gambling and violence in Tampa was also illustrated by the testimony of Charles M. Wall, a recognized power in gambling activities in the Tampa area for nearly a half century. Over a 14-year period, Wall was the target of three attempts on his life. Wall, who managed to escape on all three occasions, blandly insisted that he knew of no reason why anyone would try to murder him and admitted that no one had ever been arrested for these abortive attempts to kill him. A large portion of the testimony to the committee in Tampa dealt with the impact of unchecked gambling on the community. The committee's investigations demonstrated that illegal gambling cannot thrive without protection from law-enforcement officials. The Tampa testimony bristled with allegations of bribes to law-enforcement officials and categorical denials from such officials. The central figures in this welter of confusing testimony were Sheriff Hugh L. Culbreath, State attorney J. Rex Farrior, and retired Chief of Police J. L. Eddings. Sheriff Culbreath had his opportunity to refute the accusations of graft and official misconduct at the Tampa hearing and again in Washington. Farrior appeared in Washington and denied that he was the recipient of graft payments. The committee had no way to establish the truth or falsity of these denials. Nevertheless, when Farrior was questioned about the lax enforcement of the gambling laws in the Tampa area., he took refuge in double talk and attempted to evade responsibility by blaming others for his failures. Eddings was invited by the committee to appear in Washington but declined the opportunity to answer the allegations of misconduct voiced by several witnesses at the Tampa hearings. After his appearance before the Kefauver committee, Sheriff Culbreath was indicted by the grand jury of Hillsborough County, Fla., for taking bribes and for acts of nonfeasance and misconduct in office. The committee pointed out that Culbreath never satisfactorily explained how his net worth grew from approximately $30,000 to more than $100,000 during his years as sheriff of Hillsborough County. Nor did Sheriff Culbreath satisfactorily explain his association and business relationships with Salvatore "Red" Italiano, a notorious gang leader in the Tampa area, who consistently evaded the subpoena of the committee. Difficult to understand also was the real estate deal between Culbreath and John Torrio, Capone's predecessor in Chicago. Finally, the committee continued to wonder how a sheriff sworn to uphold the law could permit his brother and one of his employees to carry on bookmaking operations, right in the county jail. Charlie Wall's long and notorious career as Tampa’s crime boss ended in the late 1940s when the Trafficante family gained enough strength to force Wall into retirement. After a brief hiatus in Miami, Charlie Wall, still symbolizing the power and prestige of an older generation of criminals, returned home.

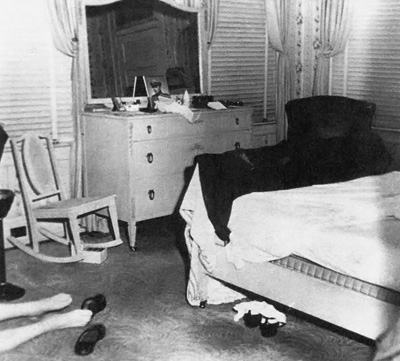

One night in April of 1955, Wall was drinking at his favorite night spot on Franklin St. and was offered a ride home by Italian gambler Nick Scaglione, whom he knew very well. That was the last time anyone saw Charlie Wall alive. The deacon of Tampa's underworld died unceremoniously in his palatial Tampa home, found murdered in his bedroom. He had been beaten with a baseball bat, stabbed 10 times and had his throat cut. Next to his bloody body lay a copy of his testimony given before the Kefauver Committee. Scaglione reported dropping off Wall early in the evening, and from then on, his whereabouts were meticulously proven--his alibi was air-tight. Joe Bedami was a suspect in the killing of Charlie Wall, though he was never arrested or charged, and the gangland murder of Charlie Wall remains unsolved.

Excerpts from a paper by Dr. Frank Alduino, Anne Arundel Community College, Arnold, Md., read before the annual meeting of the Florida Historical Society, Tampa, May 11, 1990 "The Damnedest Town This Side of Hell: Tampa 1920-29 (Part 1)" By Dr. Frank Alduino. Other sources include:

Kefauver Committee Interim Report

|

|

||||||||||||

Page1 | Page2 | Page3 | Page4 | Page5 | Page6 | Page7 | Page8 | Tampapix Home

|

|||||||||||||