|

WERE THE STRINGERS IN TAMPA BEFORE THE

SEPT. 1848 HURRICANE?

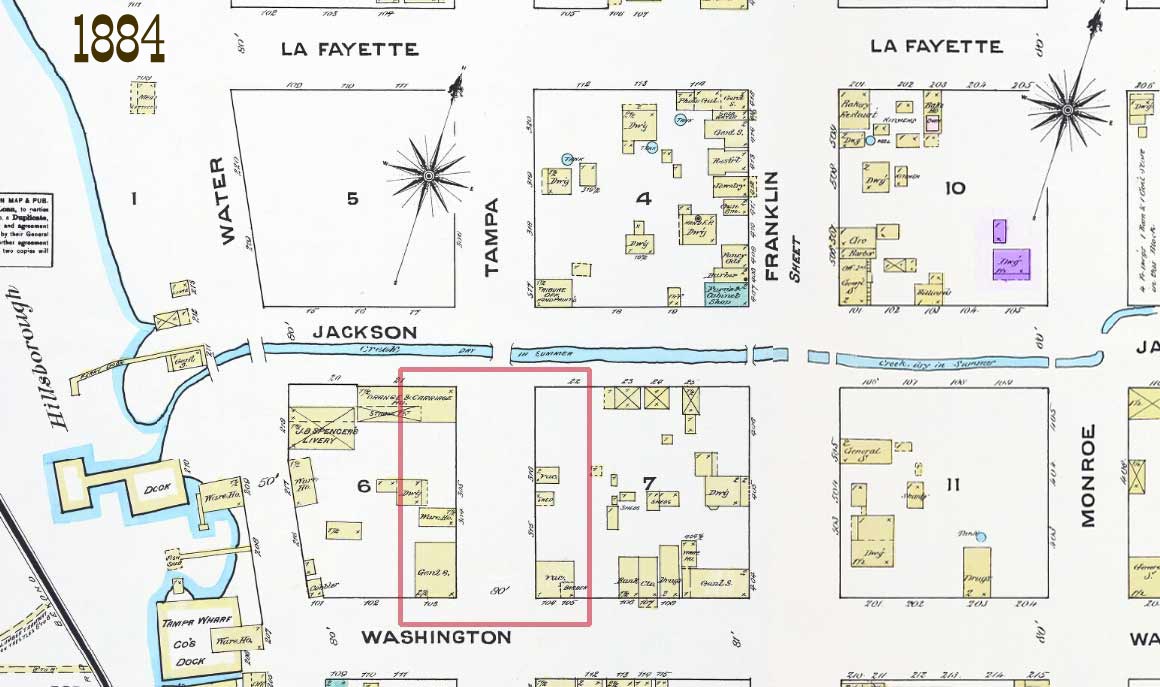

This 1884 Sanborn map

shows the area on Tampa Street between Jackson and Washington

where John Jackson's home was located in 1848. The dwelling

in purple shows the Stringer house still in existence.

Notice the proximity to the river of the location of the Jackson

home compared to that of the Stringer home. There is no

doubt that this whole area flooded.

And finally, Mary Stringer would have been around 48 years old at

the time. Thomas Jackson may have considered her to be an

elderly or old lady at the time of the storm, but Thomas claims it

was his parents who related these events to him. John

Jackson was 36 in 1848. Would he have referred to Mary as

being "elderly" or an "old lady?"

|

| IF THE HISTORIC STRINGER HOUSE WAS BUILT

BEFORE THE SEPTEMBER 1848 HURRICANE, COULD IT HAVE SURVIVED?

In "The most terrible gale ever

known" - Tampa and the Hurricane of 1848, by Canter Brown, Jr.,

he described Tampa outside of the Ft. Brooke garrison before

the hurricane:

| A few houses dotted the

landscape inside Tampa’s surveyed limits east of the river.

Among them, widow Mary Stringer occupied a dwelling where

Tampa’s city hall now stands. The A. H. Henderson family

lived on Florida Avenue at Whiting Street, while surveyor John

Jackson had erected a home on Tampa Street, between Jackson

and Washington. The Darling & Griffin store (later called

Kennedy & Darling) sat at the corner of Whiting and Tampa

Streets. East along the north side of Whiting Street near the

river (Water Street) rested the town’s principal hostelry, the

Palmer House Hotel, operated by Port Collector John M. Palmer

and his wife Margaret F. Palmer. A walk of a "few hundred

feet" north brought visitors to the L. G. Covacevich home. At

or near the foot of Lafayette Street close to the river came

Judge Steele’s former residence, a Seminole War blockhouse,

and the Simon Turman and William Ashley homes. A "trail"

connected the heart of town lying along the riverside and

Whiting Street with the remote courthouse site. |

You can read Canter Brown's entire article here in the PDF at the USF

Digital Library Collections.

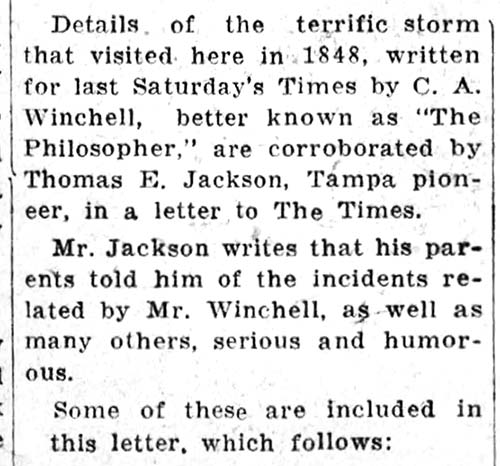

Two of the sources

for Brown's article are newspaper articles. One was Thomas E.

Jackson, "Storm of 1848 Was Real Thriller, Says Thos. E. Jackson,

Pioneer Tampan, In a Letter to the Times," Tampa Daily Times,

October 18, 1924.

In this Times article,

the author uses comments by Thomas E. Jackson, a son of the first

surveyor of Tampa, former short-time mayor and merchant, John

Jackson, to corroborate details of an article about the great gale

which appeared a week earlier. Thomas was born in 1852, four

years after the hurricane. His account is by memory of what

his parents and others may have told him, and he is retelling this

over 50 years after hearing it from his parents.

THE TAMPA TIMES - Oct. 18, 1924

|

|

|

|

|

|

Notice that Thomas Jackson

describes the scene at his parents' house, but does not say

who the "elderly lady" was. |

This newspaper article

can be seen in its entirety

here at TampaPix. Click that newspaper article to see it full

size.

|

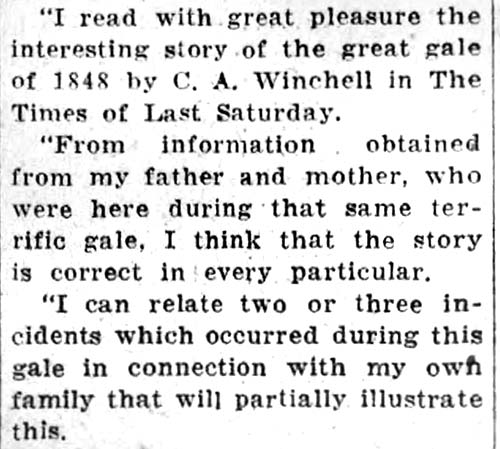

The article

above references an article of the previous week. That

article by C. A. Winchell describes much more of the

hurricane. His sources of the storm's details were

existing accounts by W. G. Ferris and his son, Josiah

Ferris. The article first describes Tampa before the storm,

then the details of the hurricane, then the aftermath.

|

|

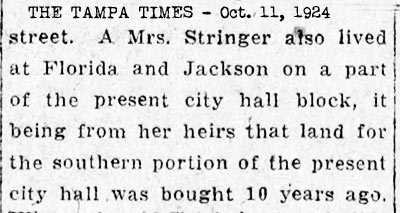

Above, the only mention of the Stringer family in that

article.

The first page of this newspaper article

can seen

in its entirety here at TampaPix. Then click the

newspaper article to see it full size.

The article concludes on a 2nd page here. |

|

|

More from Canter

Brown, Jr.'s article "The most terrible gale ever known" -

Tampa and the Hurricane of 1848"

The blow

arrived in earnest at about 8:00 a.m. on Monday, the 25th.

A shift in the wind from the east to the southeast heralded

the change. That night, the bay glowed with a phosphorescent

sheen. Come Sunday morning, winds commenced gusting from the

east, followed by intermittent showers.

|

|

|

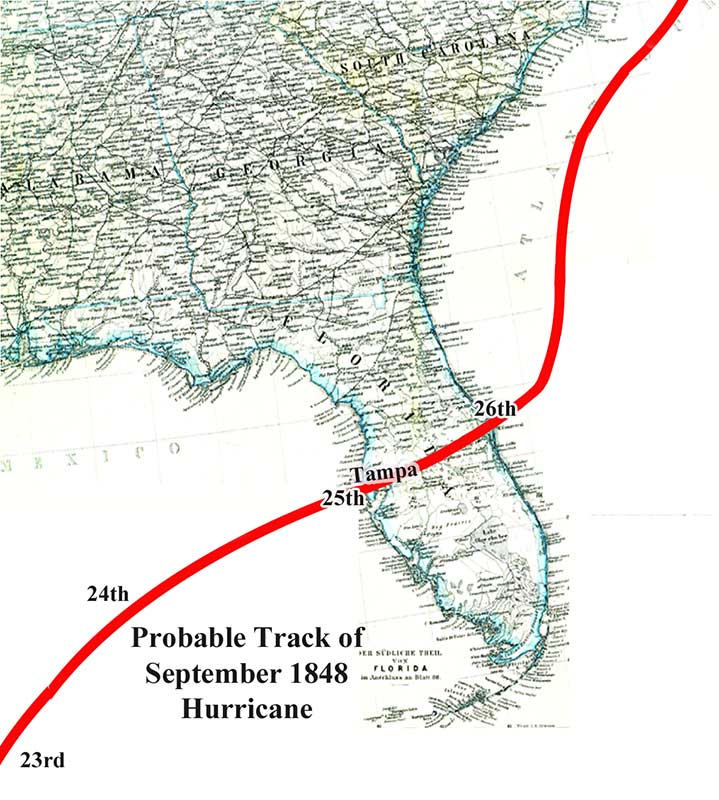

1848 map from

Exploring Florida Maps; a part of Maps ETC and

Exploring Florida websites. Produced by the Florida

Center for Instructional Technology College of

Education, University of South Florida. |

Most Tampans

failed to react quickly to the threat. As the winds grew in

intensity, they looked on from their homes as live oaks and

shrubs took the brunt of the early going. "In the morning

before the storm came to its full height," recorded an Axtell

family member, "we watched from the front windows the falling

of some of the most beautiful trees that ever graced Tampa."

Then, at 10:00

a.m. the tide commenced to rise. A young woman who endured the

storm insisted that "at one time it rose five feet in fifteen

minutes." The water quickly submerged the shore, blown toward

the post and village with terrific force by the hurricane

winds. Caught unprepared, local residents panicked, especially

those who lived near the water. "Our house was blown down in

part, and the waters from the bay swept around it in fearful

violence," declared Juliet Axtell. "We escaped from it in the

midst of the fearful tempests," she continued, "the roofs of

buildings flying round us and the tempest raging at such a

rate that we were unable to keep our feet or wear any extra

clothing such as a shawl, to protect us from the piercing

rain."

The Ferrises,

McKays, and others who did not enjoy military or

quasi-military standing headed into the village to the Palmer

House. [This was on the north side of

Whiting St. near the river.] Many arrived between 11:00

a.m. and noon to discover that "dinner" had been laid out on

tables in the hotel’s dining room. At about the time Ferris

reached safety, likely just after 1:00 p.m., the tempest

reached its full power.

An account

which suggests that a tidal surge or "wave" hurled the flood

waters to new levels, W. G. Ferris witnessed the results.

"Looking southward he saw the commissary building floating

directly towards the store, and it was apparently coming ’end

over end,’" the Ferris account related. "Part of the time it

seemed to ride the big waves, then it would sink away between

them, but all the time, and that means only a few seconds, it

rolled and tumbled straight on towards the doomed buildings.

Finally it struck the warehouse.

As the tidal

surge or wave sped the flood toward Tampa’s higher elevations,

the panic originally felt by those who resided near the water

spread generally. For example, an estimated fourteen or

fifteen persons had gathered at the newly constructed and

sturdy John Jackson home. Ellen Jackson, a bride of only one

year, made them comfortable in the absence of her husband, who

was away with a survey crew near today’s Pasco County

community of Elfers. The refugees’ sense of comfort and safety

soon proved false, however. The rising tide surged under the

house, and its waters poured into the building.

Events at the

Jackson home then proceeded at a maddening pace. One elderly

woman, likely Mary Stringer,** expressed

the terror that she felt by voicing an acute fear of getting

her feet wet. "When the water began to come into the house

this lady and others got up on the chairs and from there to

the tables," recalled son Thomas E. Jackson. "When the house

began to rock on the blocks, a change to some other refuge was

contemplated," he added. "The old lady selected old

Captain Paine, a large portly gentleman, to bear her out and

keep her feet dry." Jackson concluded, "This Captain Paine

consented, but, unfortunately, when he left the porch, he

became entangled in a mass of drifting fire place wood, and

the couple were soon prostrate in the surging waters."

Subsequently, the house floated off its blocks and "crossed

the street and bumped into three large hickory trees that

barred its way for hours."

After 2:00

p.m., the winds began slowly to subside as they shifted from

southwest to west-north-west. Still, according to Major Wade,

they "raged with great violence until past 4 P.M., after which

they lulled very much toward 8 P.M." |

**

It appears that Brown has added the suggestion that the elderly

woman in the Jackson home was "likely Mary Stringer." It is Thomas

Jackson who first describes the frightened woman as an "elderly

lady" and "old lady" but doesn't identify her. Would

Thomas' mother have described Mary Stringer as an elderly or old

lady at age 50 or so? No mention is made by Jackson of

Mary's children escaping the Jackson house; Sheldon would have

been around 13, Laura around 11, and if Samuel was there, he would

have been 17. It is doubtful that Mary would have left her

house to take refuge in another house without her children. If she

was in the Jackson home with her family, it probably would have

been because the Jackson home was thought to be sturdier.

But the Jackson home, at Washington and Tampa Streets, was closer

to the bay and the river and would have flooded from the tidal

surge before the Stringer home. Would Mary have left her

house to go to one closer to the flooding?

|

|

The Great Gale of 1848 at Wikipedia

The 1848 Tampa Bay hurricane,

also known as the Great Gale of 1848, was the most severe

hurricane to affect the Tampa Bay area and is one of only

two major hurricanes to make landfall in the area, the other

having occurred in 1921. It affected the Tampa Bay Area

September 23–25, 1848, and crossed the peninsula to cause

damage on the east coast on or about September 26. It

reshaped parts of the coast and destroyed much of what few

human works and habitation were then in the Tampa Bay Area.

Although available records of its wind speed are

unavailable, its barometric pressure and storm surge were

consistent with at least a Category 4 hurricane. A survivor

called the storm "the granddaddy of all hurricanes."

The storm appears to have

formed in the central Gulf of Mexico before moving northeast

to make landfall near Clearwater, Florida. It then crossed

the Florida peninsula and exited near Cape Canaveral.

After moving into the extreme western Atlantic, the cyclone

continued to the northeast just offshore of the East Coast

of the United States to the Grand Banks of Newfoundland.

Fort Brooke recorded peak

winds of 72 miles per hour, and a barometer at the fort

measured a minimum pressure of 28.18 inches of mercury (954

mb), though the winds were still blowing at the time that

reading was made. The storm produced the highest storm tide

ever experienced in Tampa Bay. The water rose and fell about

15 feet in six to eight hours. The tide inundated Pinellas

County “at the waist,” covering all low-lying elevations,

and reportedly submerged most of the Interbay Peninsula,

where South Tampa and MacDill Air Force Base currently

reside. “The bays [Hillsborough and Old Tampa] met.” General

R. D. A. Wade, commanding at Fort Brooke, reported the

destruction of the wharves, public buildings, and

storehouses. B. P. Curry, the fort’s assistant surgeon,

reported the hospital destroyed. Only five houses were left

standing in Tampa, and they were all damaged. The water rose

twelve feet higher than had been noted in the past, and

strong winds downed many old trees.

On the Pinellas Peninsula,

the storm destroyed the fishing rancho of Antonio Máximo

Hernández, reputedly lower Pinellas’ first white settler,

forcing him to emigrate permanently. The storm almost

obliterated the citrus crop and destroyed the main house at

St. Helena plantation—now part of Safety Harbor—forcing the

residents to shelter on an elevated Tocobaga mound. Even so,

they nearly drowned as the storm tide eroded part of the

shell mound. Winds also felled almost all of the trees along

what is now Indian Rocks Road in Largo.

The storm completely

altered the coastal geography of the Tampa Bay area, cutting

new inlets, filling in others, and altering the shape of

bays and keys, thereby making navigational charts useless to

mariners. Allen’s Creek was widened from less than 200 feet

to about half a mile at its mouth. Passage Key, between

Egmont Key and Anna Maria, was obliterated but reformed

later. The storm created what would become known as

“Soldier’s Hole” at Mullet Key, so called because soldiers

at Fort De Soto used it as a swimming hole. John’s Pass was

opened but has since shifted north. After the storm

destroyed the lighthouse on Egmont Key, the keeper (Marvel

Edwards) rode out the storm in a rowboat tied to a palmetto

tree. The end of the rope was later found 9 ft. off the

ground, which had an elevation of about 6 ft.

|

By James McKay,

Jr. in "Reminiscences

- History of Tampa in the Olden Days" Dec. 18,

1923 and "Oldest Tampa Citizen Recounts Tampa's Deeds,"

Dec. 20, 1921, Tampa Times.

In 1848, the town was visited

by a terrific hurricane causing the tide to rise above 15

feet above low water mark, washing away the W. G. Ferris

store and the house we were living in; in fact, most of the

houses that were located on the river bank.

At this time, my father was

absent at New Orleans with his schooner, the Wm. H. Gotzmer,

this vessel at that time being the only means of

transportation with the outside world in securing supplies

for the small colony of Tampa.

Our family was moved to the

Palmer hotel, and when driven out of there on account of the

tide, to the Darling and Griffin store, and then to the

military hospital on the reservation.

The Palmer Hotel withstood the hurricane, although the water

rose two feet over the main floor.

After the hurricane, the

military authorities issued my mother tents to house our

family, which, with their assistance, was placed on the

block now occupied by the Knight & Wall Hardware Co., that

block at the time being owned by my grandmother, Sarah Cail.

When my father returned

in his vessel, he had some logs cut and hauled in and a

house built, where we lived for some 20 months, until he

could bring lumber from Mobile and build a house on the

block now occupied by the Almeria Hotel.

As soon as Mr. [W. G.]

Ferris could

obtain material he erected a small building on the south

side of Whiting street near the intersection of Franklin,

which did not extend farther south, on account of the

reservation.

A few years later Mr. Ferris,

having some trouble with the military officials, was ordered

off the reservation, so he moved his store to the corner of

Florida and Washington streets and built his residence on

the same lot. This residence became the old folks home and

later on was moved to the site the home is now occupying and

somewhat improved, or made larger.

(See this house) |

E.

L Robinson's account of the storm: E.

L Robinson's account of the storm:

The turbulent

weather preceding the great storm of 1848 commenced on

Saturday, September 23. During Sunday the wind came in gusts

from the east accompanied by occasional showers. A number of

men went down the bay on Sunday to assist in bringing in W.

G. Ferris' schooner, the John T. Sprague, due from New

Orleans with a cargo of supplies. Great difficulty was

experienced in towing the vessel against the strong wind,

and it was necessary to "kedge" (move by hauling in a thick

rope or cable attached to a small anchor dropped at some

distance) more than once before reaching the landing. It was

well for the troops and villagers that this cargo was saved,

for it was some time afterward before more supplies came in.

The schooner also brought specie (coins) and currency to be

paid to the soldiers, Mr. Ferris being "acting'' paymaster

at the time.

On the

morning of the 26th, the wind shifted to the south and

finally to the southwest. Then the trouble commenced.

A high tide came in, and the velocity of the wind increased,

driving the water deep into the garrison. Ferris carried his

family to the Palmer House, then waded ·in "water up to his

armpits back to the store, where he succeeded in getting out

the currency and account books. Then upon looking southward,

he saw the commissary building rolling and tumbling straight

toward his warehouse. A moment later there was a crash as

the warehouse was struck and away went the whole structure,

reduced to a mass of wreckage that included $15,000 worth of

goods and a large amount of specie.

The Palmer

House now seemed doomed. Tables began to float around in the

dining room of the old hostelry. Josiah Ferris, son of the

sutler, distinguished himself by swimming out through the

north door with a young girl in his arms. The refugees

retreated to the Kennedy store, thence to still higher

ground at the corner of Franklin and Washington. But the

Palmer House withstood the storm. The scene in the garrison

was now appalling, though sublime in its grandeur, as the

great waves came charging in, and the bay as far as the eye

could reach was lashed to a fury. The islands in the bay

were out of sight under the water, and the tidal wave rushed

across the peninsula west of the river into Old Tampa Bay.

The tremendous pressure of wind and water raised the river

until only the treetops were visible, far north of the

village. The Sprague, with the government specie still on

board, had been anchored up at the ship yard," and during

the worst part of the gale the hull of an old abandoned boat

floated against her and broke her cables, allowing her to

drift out into the pine woods east of the river and

somewhere west of what is now Franklin street with captain

and crew still on board.

During

Monday afternoon the wind died away and the waters receded

somewhat, giving the villagers an opportunity of viewing the

damage. In the garrison they found that the little church on

the beach, the soldiers' quarters near by, C. B. Allen's

boarding house, the Indian agent's office and the Ferris

property had been wrecked, and all other buildings in that

locality more or less damaged. North of Whiting street, the

block house and the Turman and Ashley residences had been

swept away. The roof of W. S. Spencer's house was blown off.

The residence of Capt. James McKay, Sr., was spared.

|

|

On Tuesday

morning the men from the Sprague came down out of the woods

and brought some coffee, hard bread and other needed

supplies. Learning that the food on the vessel was intact,

the commander at the fort sent a detail of soldiers to bring

the supplies to the village and these were divided between

the storekeeper and the troops. Later, the government paid

for these confiscated goods. Ferris' stock was scattered all

the way from Sulphur Springs to Gadsden Point. Several days

later the strong box was recovered by the sutler, the specie

(coins) intact.

Whiskey flowed freely on the evening following the gale,

several barrels of the potent stuff having been salvaged

from the bay and river. Most of the liquor as well as a

number of cases of wine was turned over to the post

commander, however. A number of cedar logs which

Ferris had kept in a "bight" on the Alafia river were

scattered along the shore from a point up the river around

to the north shore of Old Tampa Bay. It is said that the

waters of the bay were phosphorescent during several nights

preceding the gale, and on Sunday night the light from this

source was "almost bright enough to read by."

The village

school, taught by a Mr. Wilson, had been dismissed on the

forenoon of the day of the gale, and Mr. Henderson, who was

one of the pupils, said that the velocity of the wind was so

great the people were forced to hug the ground in order to

get anywhere. During the storm the lighthouse at Egmont was

so badly damaged that a new one was built. No lives were

lost as a result of the gale, but there were many narrow

escapes from death. As to the cause of the inundation,

various theories were advanced. Many were of the opinion

that the east wind had blown great volumes of water into the

gulf, and that the south wind coming on with the tide, drove

the waters of the overtaxed gulf into the bays along our

coast. Of such was the memorable storm of '48.

History of Hillsborough County, Florida, Narrative

and Biographical, 1928" by Ernest L. Robinson,

Director of High Schools of Hillsborough County, Formerly

Principal of

Hillsborough County High School. |

|