|

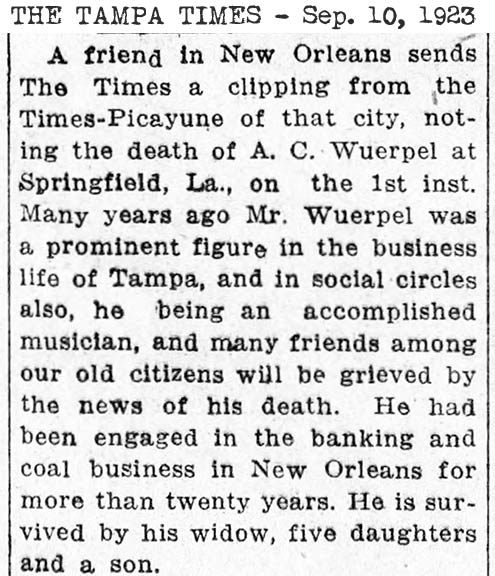

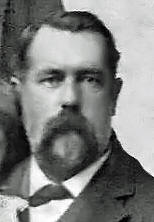

Tampa's First

Fire Chief - Augustus C. Wuerpel

This page is in the

process of being updated.

|

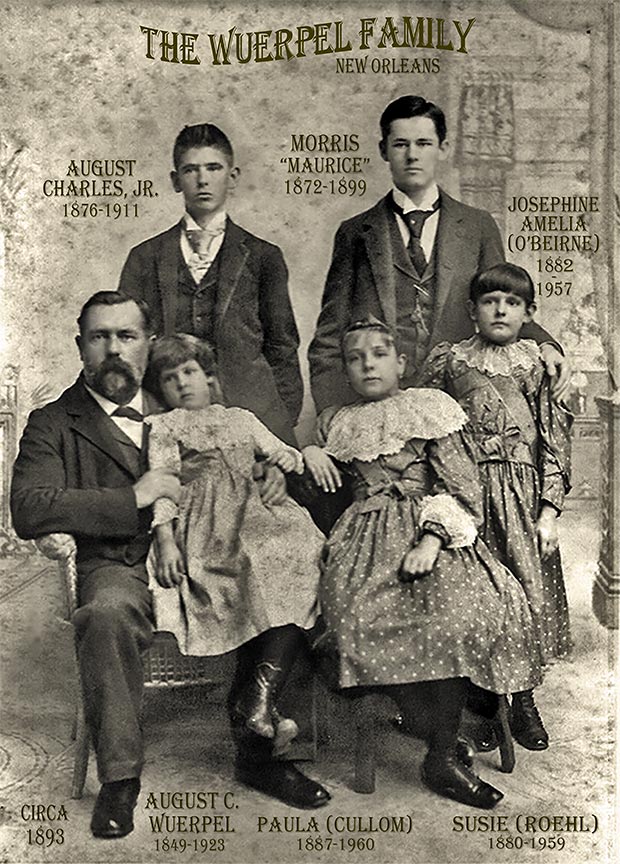

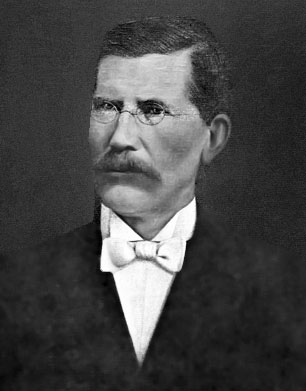

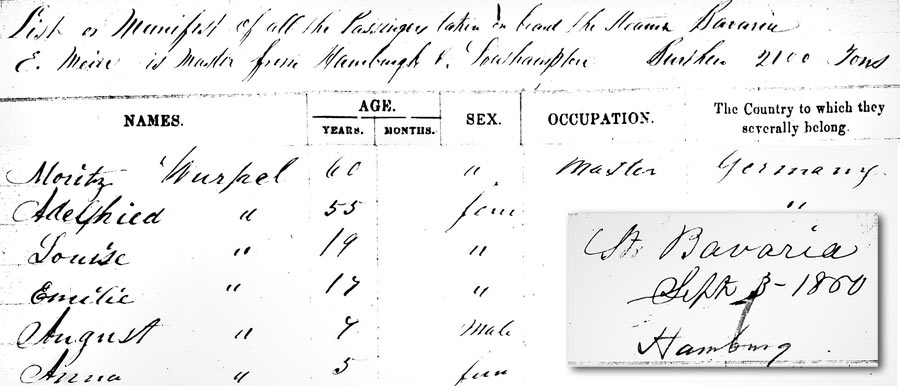

August C.

(Charles/Karl) Wuerpel was born July 11, 1849 in

Cologne, (Leichlingen, Rheinland, Preußen) Germany. He

was 11 years old when he and his three sisters

immigrated to America with their parents in 1860.

Father: Morris

(Moritz) Wuerpel b. 1801 Amsterdam, Noord-Holland d.

1865 St. Louis, Mo.

Mother: Adelheide

Trolle Wuerpel b.1805 Haute-Normandie, France, d. 1888

St. Louis, Mo.

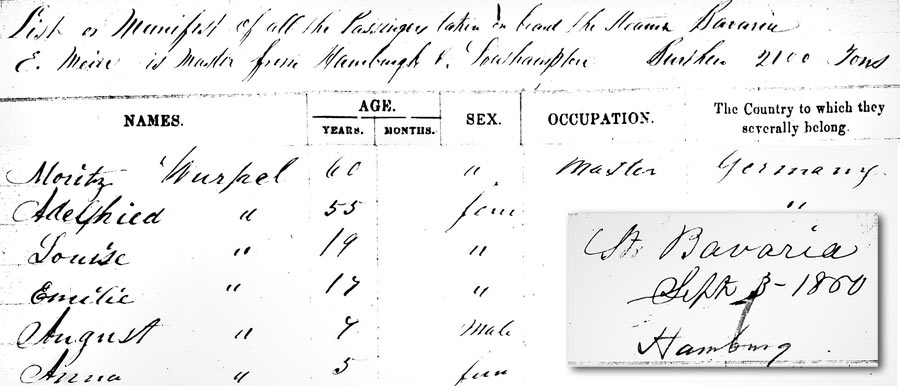

The Wuerpels came

to America on the steamer Bavaria which

departed from the port of Hamburg, GER, stopped in

Southampton, ENG and arrived at the Port of NY on Sept.

3, 1860 |

|

The

Wuerpels settled in St. Louis, Missouri where Moritz had

relatives. Moritz and Adelheid Wuerpel are both buried

in Bellefontaine Cemetery St. Louis City, Missouri. |

|

|

|

Moritz

(60), Adelhied (Adelaide, 55), Louise (19), Emilie (17), August (7),

Anna (5).

August would have been 11 here, not 7. Moritz's

occupation was listed as "Master." |

|

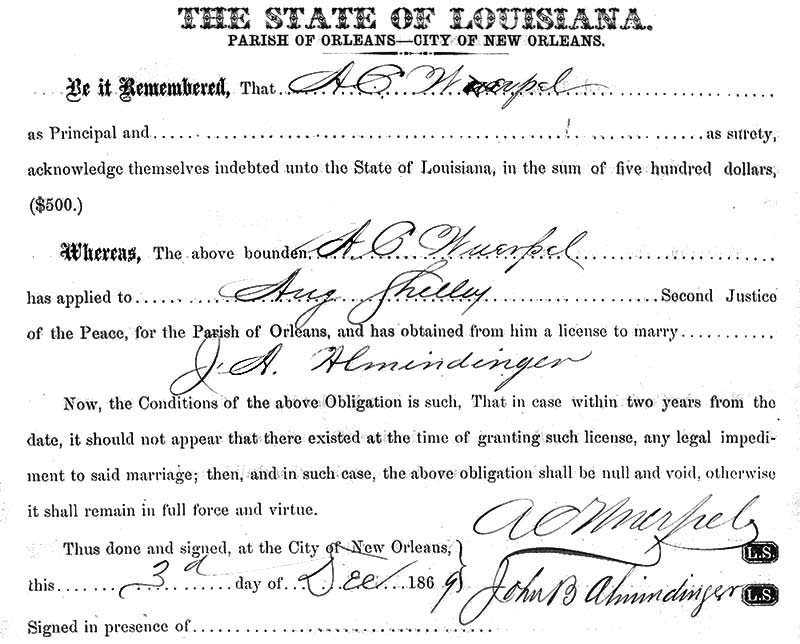

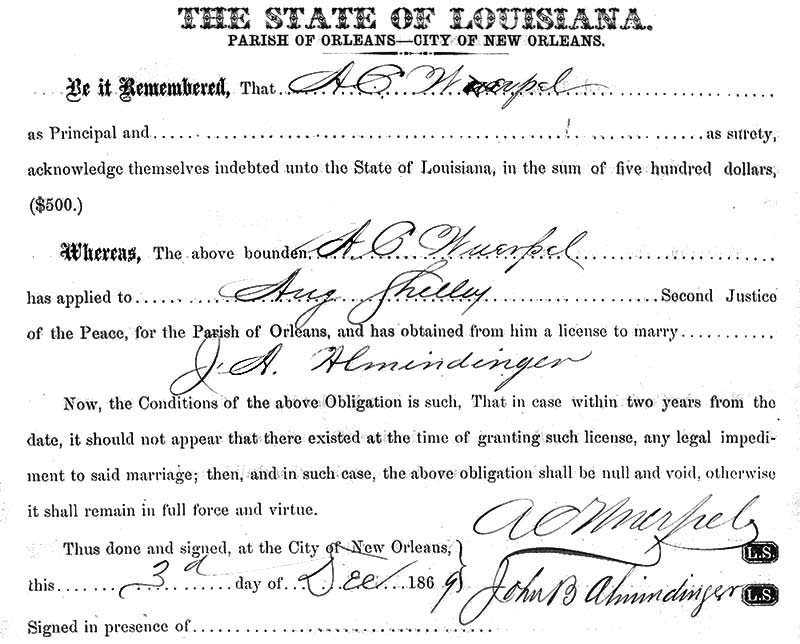

On Dec.

15, 1869, August married Josephine Amelia Almindinger at

Lafayette Presbyterian or Fulton St Church in New

Orleans. Josie was born in New Orleans in 1847, one of

at least 6 children of German born carpenter Michael J.

Almindinger and his New York-born wife Susan (according

to their 1850 Census in New Orleans, and Susan's 1870

Census in New Orleans.)

|

|

|

|

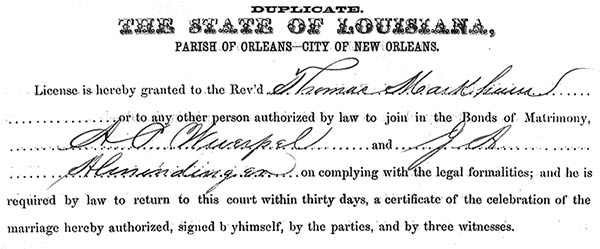

Their marriage

license was obtained on Dec. 3, 1869. It is

very rare for a New Orleans marriage record

to represent both the bride and the groom

only by their first initials and surnames.

John B.

Almindinger was Josephine's brother.

|

|

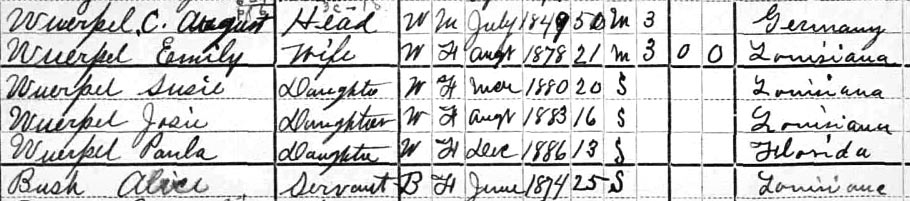

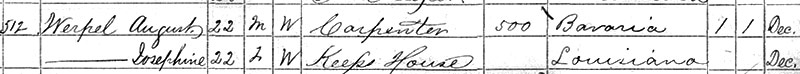

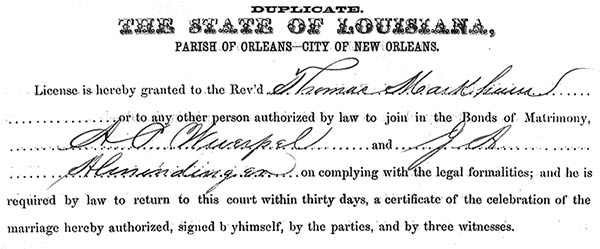

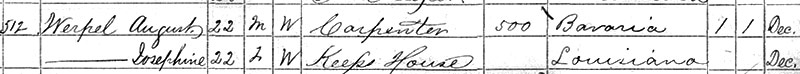

1870 Census

of August & Josephine Wuerpel

11th Ward of New Orleans

August was working as a

carpenter. His father, Moritz (Morris)

Wuerpel was a carpenter and builder in St.

Louis.

|

|

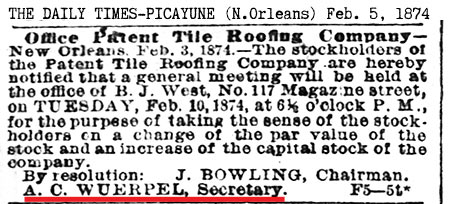

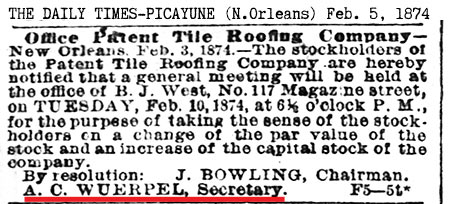

Gus was Secretary of the Patent Tile Roofing

Co. in New Orleans |

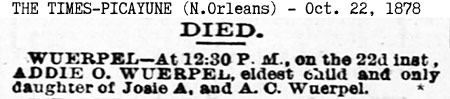

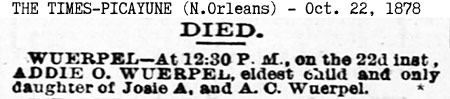

Gus and Josie's first child, Addie, was

probably named for Gus' mother Adelaide

(Troulle) Wuerpel |

|

|

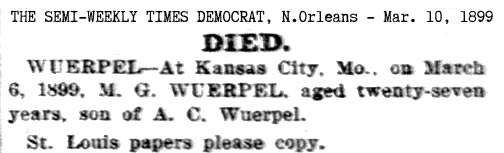

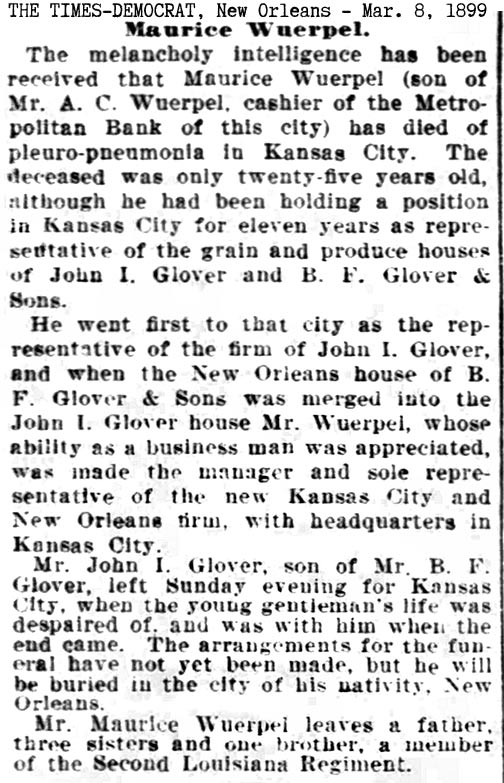

Since their oldest son Morris was born in

1872, Addie was probably born in 1871 and

would have been around 7 years old when she

died.

|

|

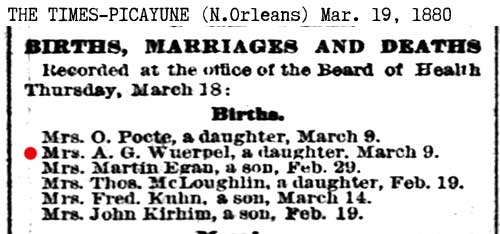

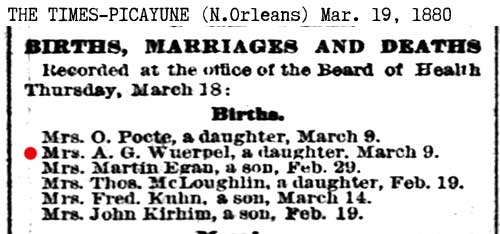

Announcement of baby girl born

to Mrs. A.C. Wuerpel on Mar. 9,

1880. This was Susie; she

appears on their 1900 census as

"1/4" year old, with her birth

month "Mch" recorded in the next

column. |

|

|

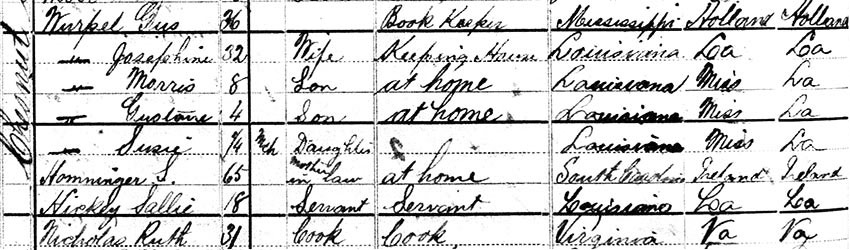

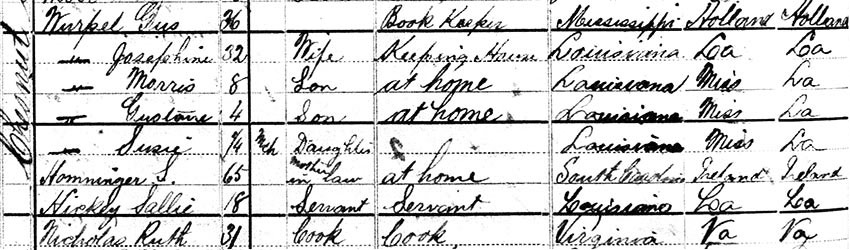

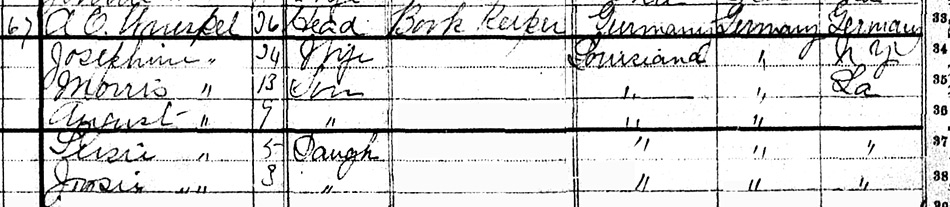

The Wuerpels'

1880 census in New Orleans shows Gus was a

bookkeeper. Wife Josephine with children

Morris, Gustave (August. Jr.) Susie, and

Josephine's mother Susan Almindinger

(widowed) was living with them. They also

had a servant and a cook.

It is not

known why Gus Wuerpel's birth place was

given as Mississippi. Perhaps the

information was given by someone in the

household other than Gus. The mistake is

propagated to their children's father's

birthplace. Josephine's parents' census of

1850 in New Orleans shows Josephine had 3

siblings born in Mississippi. Another

inconsistency is Josephine's mother's

birthplace shown as South Carolina. Michael

and Susan Almindinger's 1850 Census shows

Susan was born in New York. Susan shows up

on the 1870 Census in New Orleans living

only with H. Almindinger, who was probably

her son Horace. Again, Susan Almindinger

was listed as born in NY.

1880 Census, New Orleans, La.

The Wuerpels

were living at 235 Chesnut St. in New

Orleans. |

|

|

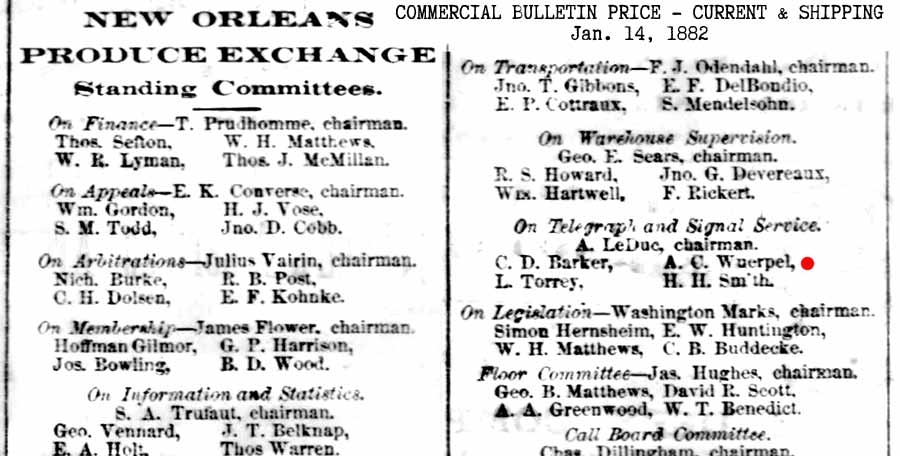

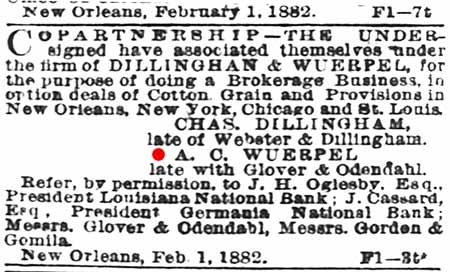

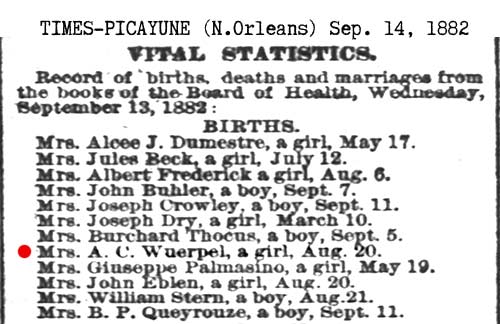

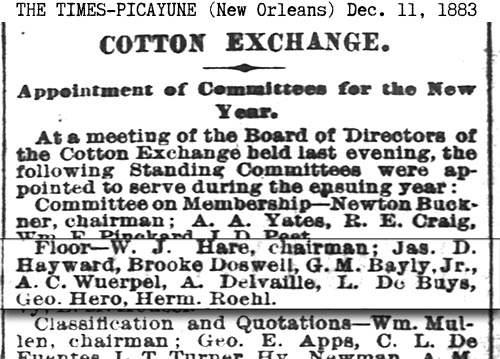

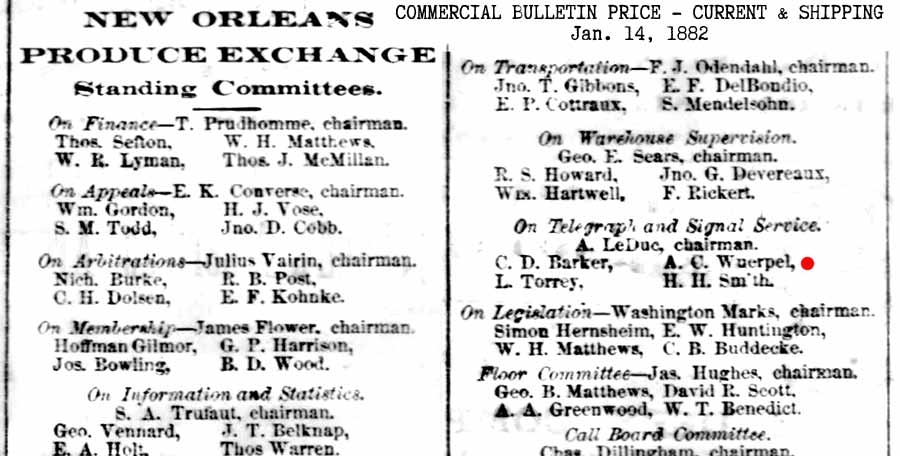

The

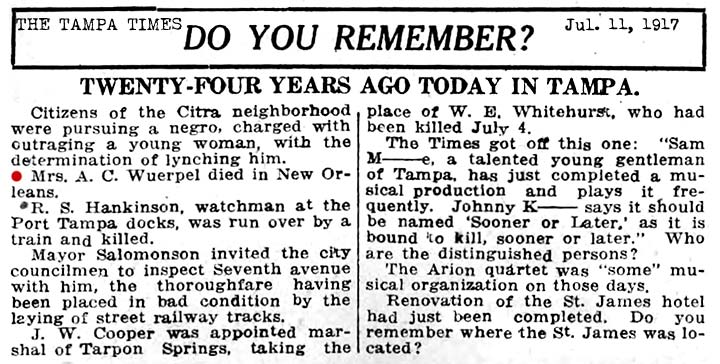

notices above place A.C Wuerpel still in New Orleans

through Jan. of 1882. Wuerpel, formerly with Gover

& Odendahl, has formed his own brokerage firm in

partnership with Chas. Dillingham, formerly of

Webster & Dillingham.

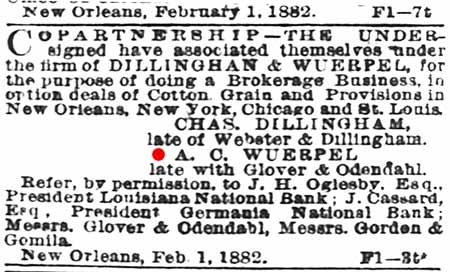

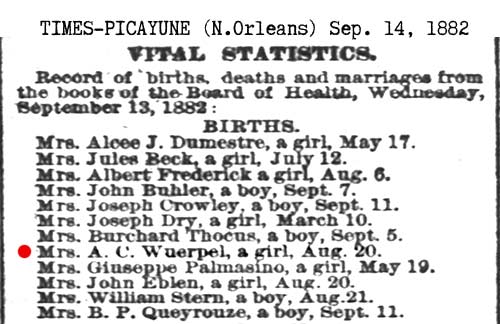

Evidence that the Wuerpels were still in New Orleans

in Aug. 1882: The Times-Picayune of New Orleans

announced the birth of a baby girl on Aug. 20,

1882, to Mrs. A.C. Wuerpel. This can only be their

daughter Josephine Amelia Wuerpel.

|

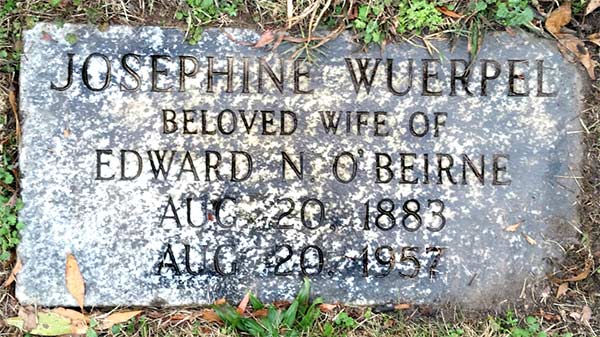

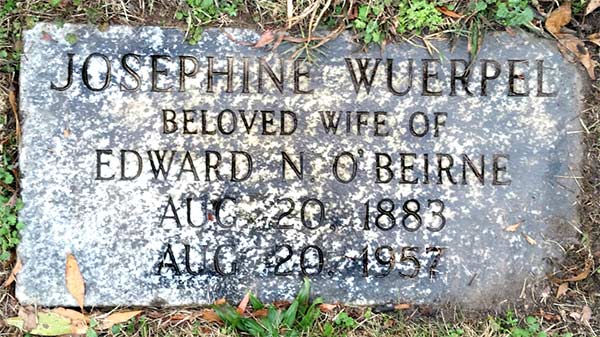

It appears that her 1900 Census

and her tombstone have incorrectly represented her birth year as

1883.

Tombstone photo courtesy of Phil at Find-a-Grave

|

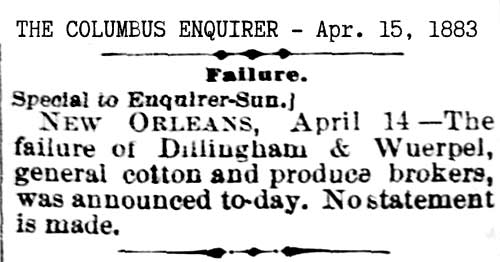

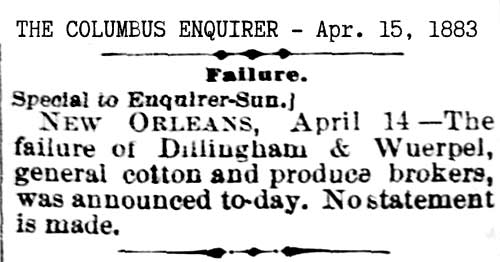

The

cotton and produce broker firm of Dillingham &

Wuerpel went "belly-up" in April 1883. |

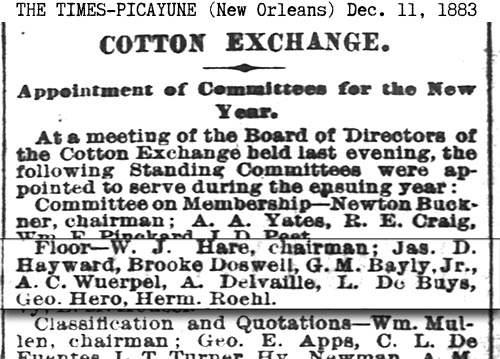

Below is the last article published in New Orleans newspapers

containing "Wuerpel" for newspapers online at Newspapers.com.

There are no mentions in 1884. |

|

|

It appears that the Wuerpels came

to Tampa in late Dec. 1883 to early 1884.

|

THE

WUERPEL FAMILY IN TAMPA

The

first official record of the Wuerpels in Tampa found

thus far is the 1885 Florida State Census where

August was working as a bookkeeper. A. C. Wuerpel

and his family were listed 5 dwellings away and on

the same page as Tampa merchant John Jackson and

John's son Thomas. This would have been in the

vicinity of Tampa Street, Jackson St. and Washington

St. Using their daughter Josie's age and birthplace,

it would appear they came to Tampa no sooner than

1883.

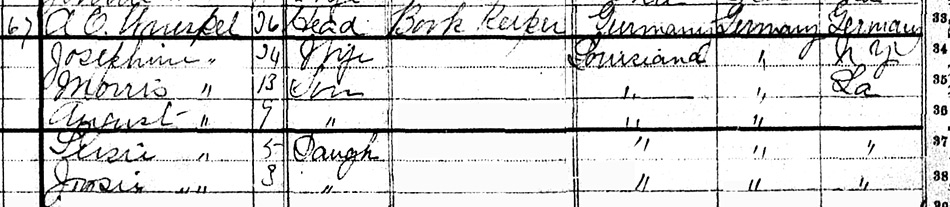

1885 Florida State Census, Hillsborough County,

Tampa

August

(36), wife Josephine (34), children all born in La.

: Morris (13), August (9), Susie (5) and Josie (3).

Further proof that Josephine (Almindinger) Weurpel's

mother was from NY can be seen on line 34, in the

last column for "mother's birth place."

TAMPA'S

WATER SUPPLY and FIRST FIRE DEPARTMENT

The formation of a dedicated fire

department in Tampa was closely tied to

Tampa's quest for a reliable water

system.

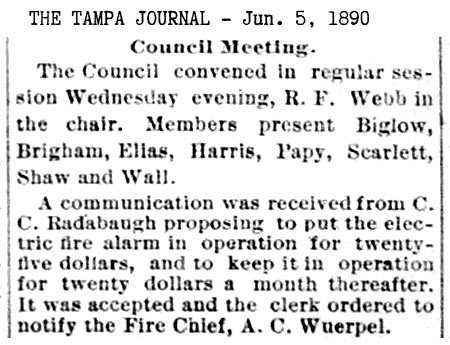

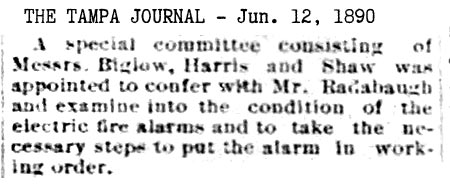

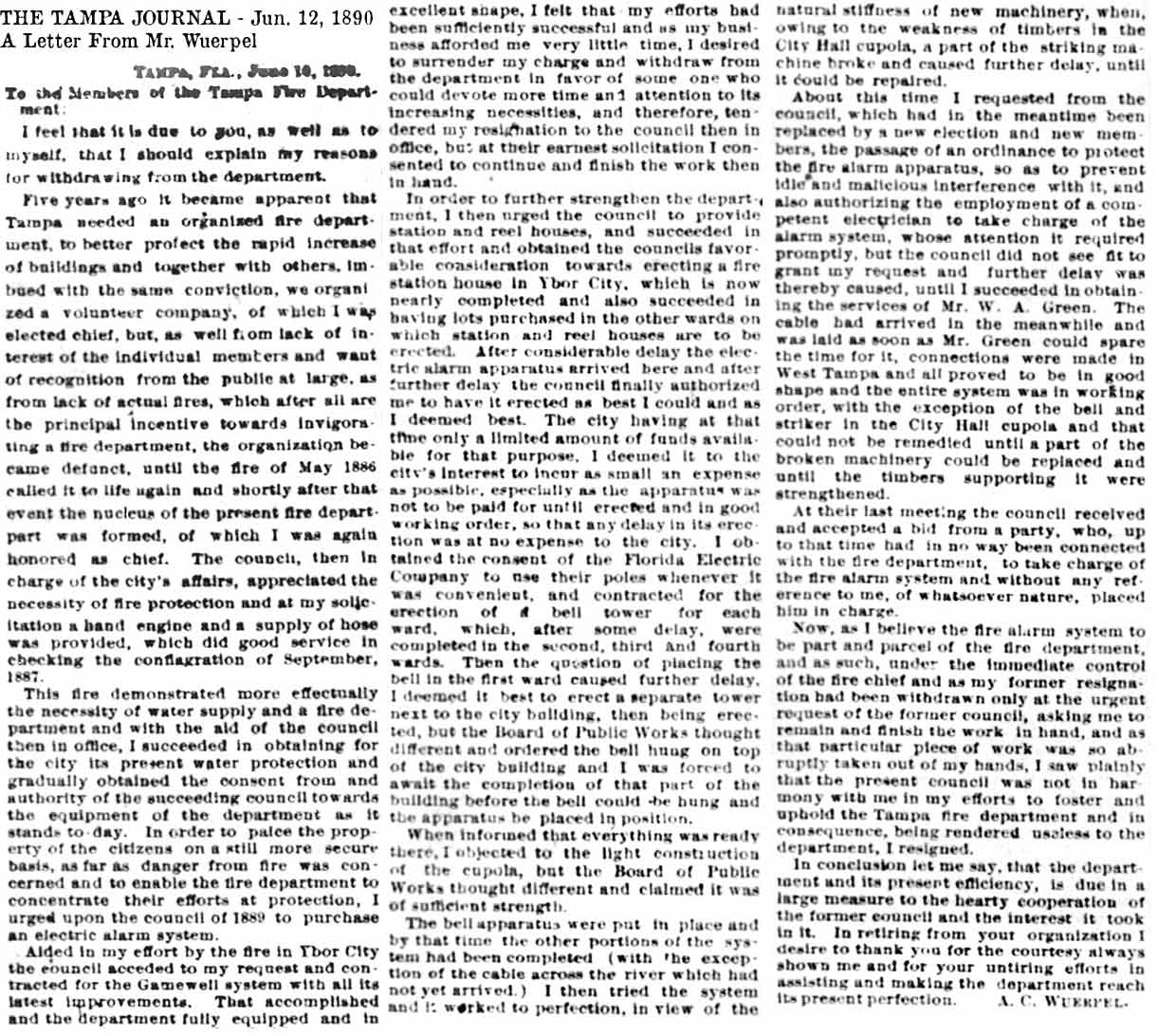

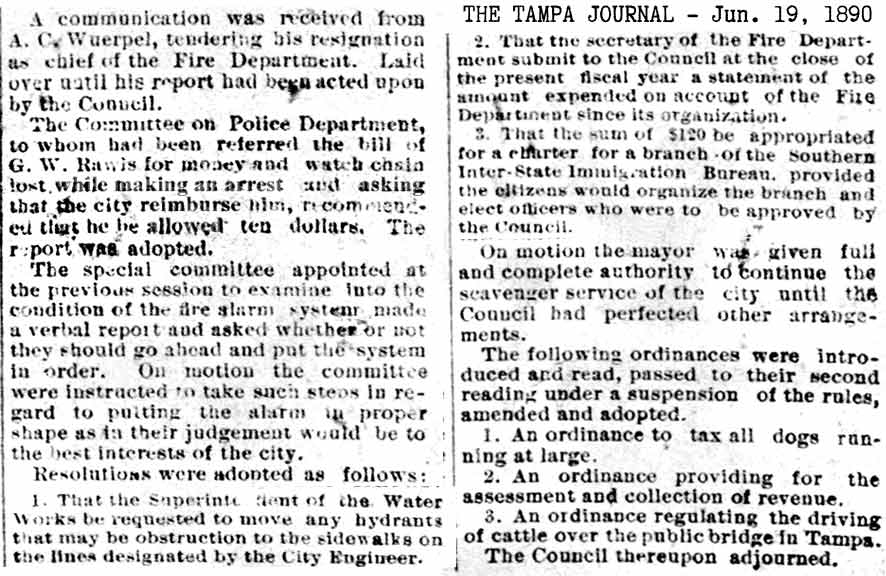

The

information presented here about Tampa's

fire department early history comes

mostly from these sources: June 10,

1890 article in the Tampa Journal, "A

Letter From Mr. Wuerpel" to the members

of the Tampa Fire Dept. Tampa Bay

History magazine at USF Scholar Commons,With

Pride and Valor: The Tampa Fire Fighters

Union. 1943-1979 by Mark Wilkins, South

Tampa Magazine, Hometown Heroes. Grismer,

Karl - A History of Tampa, and a Tampa

Tribune column of Aug. 23, 1959 Pioneer

Florida Chief

soaked in Jackson St. ditch water by

D.B. McKay. (Click the link to see

entire article, then click the article

to see full size.)

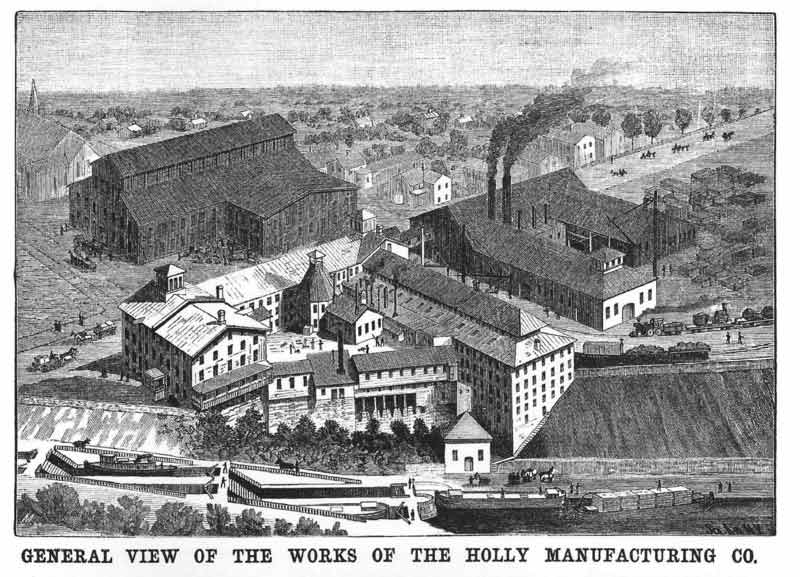

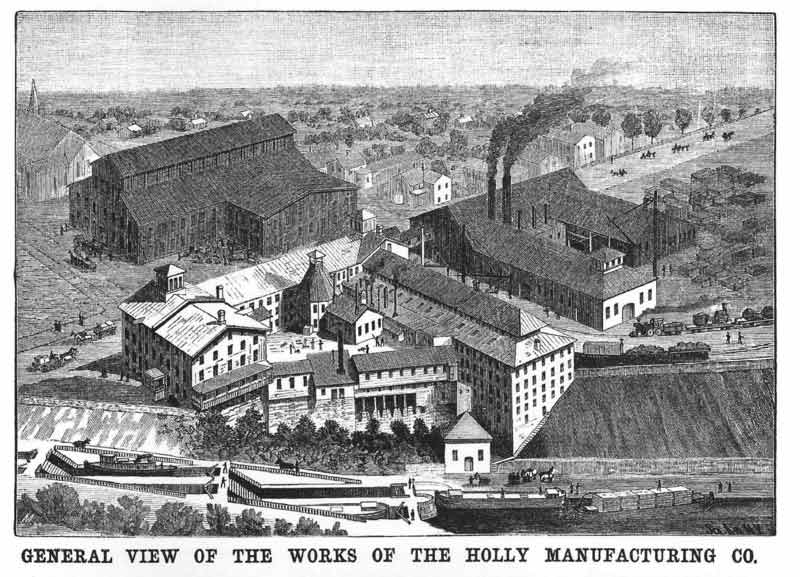

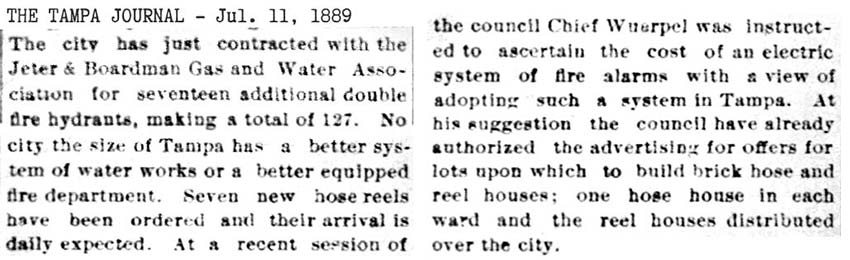

In 1885 it

became apparent to Tampa businessman

August C. Wuerpel, along with other

Tampa citizens, that Tampa needed an

organized fire department. During the

winter of 1884-85, a series of

disastrous fires convinced everyone that

a dependable water supply was essential

and on July 28, 1885, the City Council

awarded a franchise to the Holly

Manufacturing Company, of Lockport,

N.Y. The company agreed to provide

enough water for a town of 10,000 and

install fifty fire hydrants without

charge. Water rates were fixed at $8 a

year for homes and from $15 to $50 a

year for business places.

Postcard image from VintageMachinery.org

After

getting the contract, the Holly

officials lost their enthusiasm. Making

a house-to-house check to learn how many

families would take the "city water,"

they learned they could not expect to

get a gross revenue of more than $1,000

a year. That was not enough to pay

operating expenses, to say nothing of

giving a return on the initial

investment, so they understandably

proceeded to abandon the franchise.

See a more detailed history of Tampa's

Waterworks here at TampaPix.

On June 2,

1884, sixteen local citizens formed Hook

& Ladder Company No.1, a volunteer

department with W. B. Henderson as

foreman, Fred Herman, assistant foreman,

and C. P. Wandell, treasurer. Other

members were P. F. Smith, Dr. Duff Post,

Ed Morris, J. C. Cole, E. L. Lesley,

Phil Collins, S. P. Hayden, Frank Ghira,

H. L. Knight, A. J. Knight, C. L .

Ayres, S. B. Crosby and A. P .

Brockway. In 1885, A.C. Wuerpel was

appointed to be the department Chief.

[Grismer, A

History of Tampa, 1959]

Meanwhile,

repeated attempts were made to interest

other water companies to build Tampa's

water works, but all failed because

Tampa, then a non-incorporated town,

could not obligate itself to pay for

water hydrants.

[Grismer, A

History of Tampa, 1959]

Due to a

relative lack of fires, lack of interest

of the members and their desire for

public recognition, the fire-fighting

organization became defunct. Disastrous

fires of 1885 and May 1886 caused

interest to revive the fire department*

and Wuerpel was chosen as its chief with

seven "bucket brigades" organized to

serve the city.

[Grismer, A History

of Tampa, 1959, *A. C. Wuerpel

resignation letter of Jun. 10, 1890]

The only

equipment these firemen had consisted of

twenty buckets, two scaling ladders and

some axes. In these early days,

dependence for water to fight fires in

the heart of the business district was

on public wells located at various

intersections, and the Jackson Street

ditch. Bucket brigades carried the

water to the site of the fires.

[Grismer, A History

of Tampa, 1959]

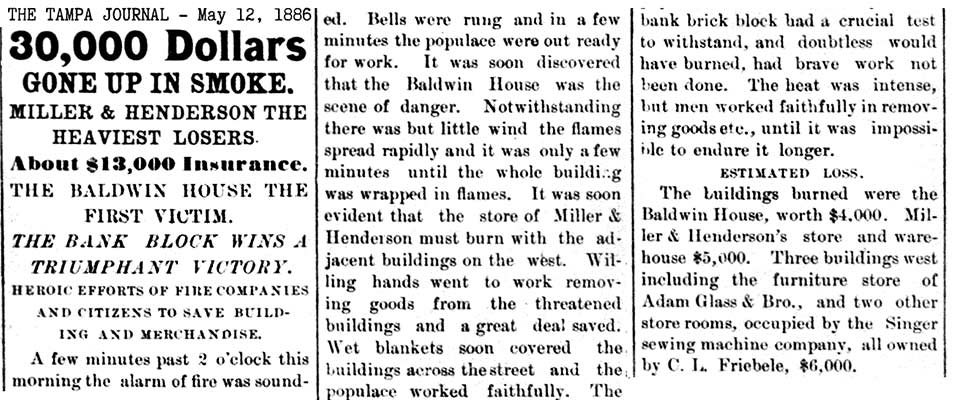

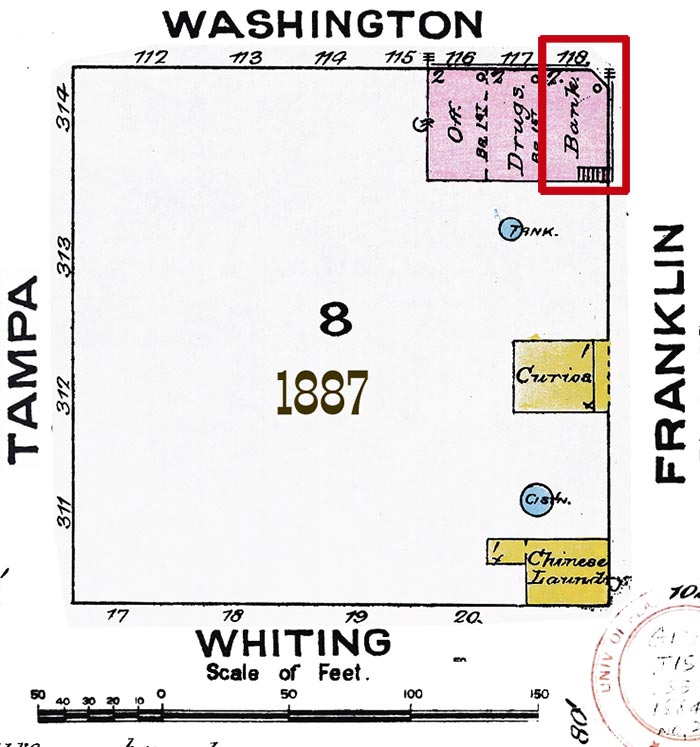

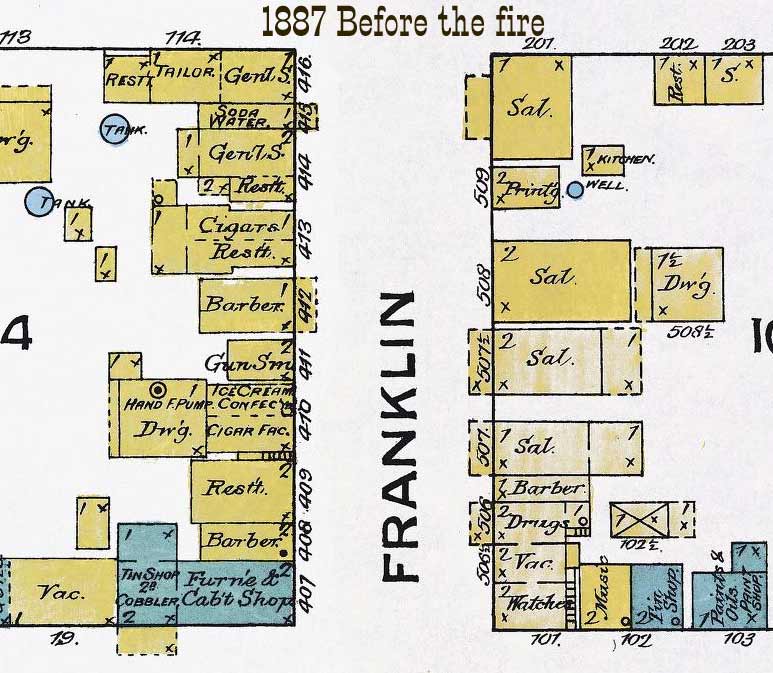

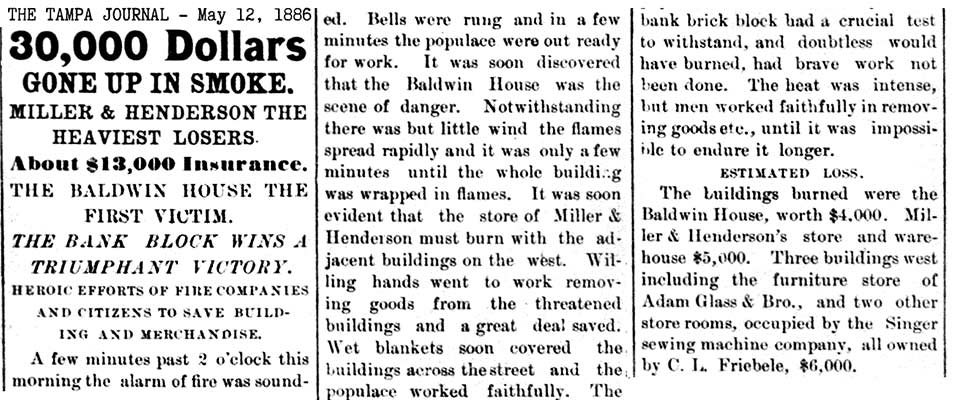

May 12, 1886 Fire

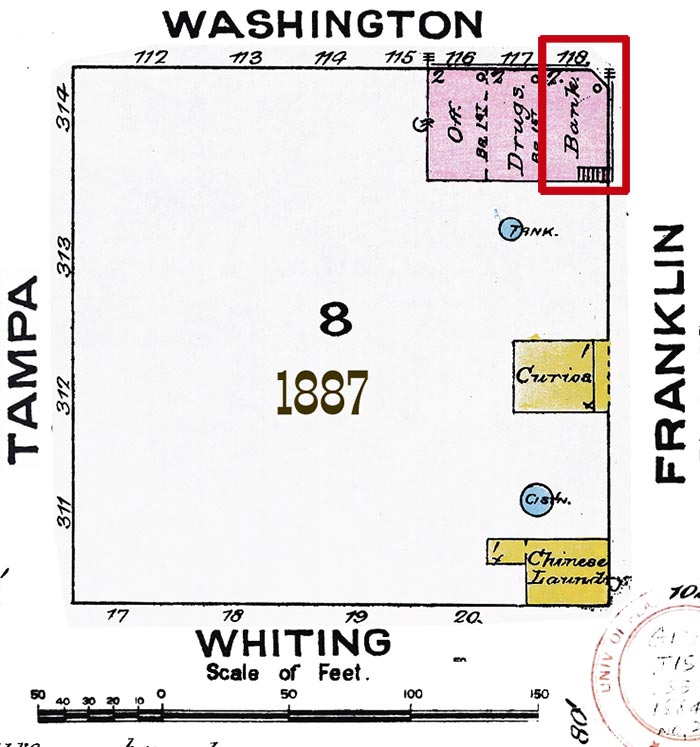

1887 -

After the May 12, 1886 Baldwin house

fire. Pink indicates brick structures,

yellow are wood frame structures.

Needless

to say, more than a little difficulty

was encountered in batting serious

conflagrations. This was clearly shown

May 8, 1886, when all the buildings

except the First National Bank were

wiped out in the block bounded by

Franklin, Whiting, Tampa and

Washington. Included among the

structures destroyed were two buildings

owned by W.P Henderson, a new store of

Friebele & Boaz, the Baldwin House, the

furniture store of A. Glass & Bros., and

the warehouse of Miller & Henderson. The

loss was estimated at $30,000.

PLACE YOUR CURSOR ON THE MAP TO SEE THIS

BLOCK IN 1884, before the fire.

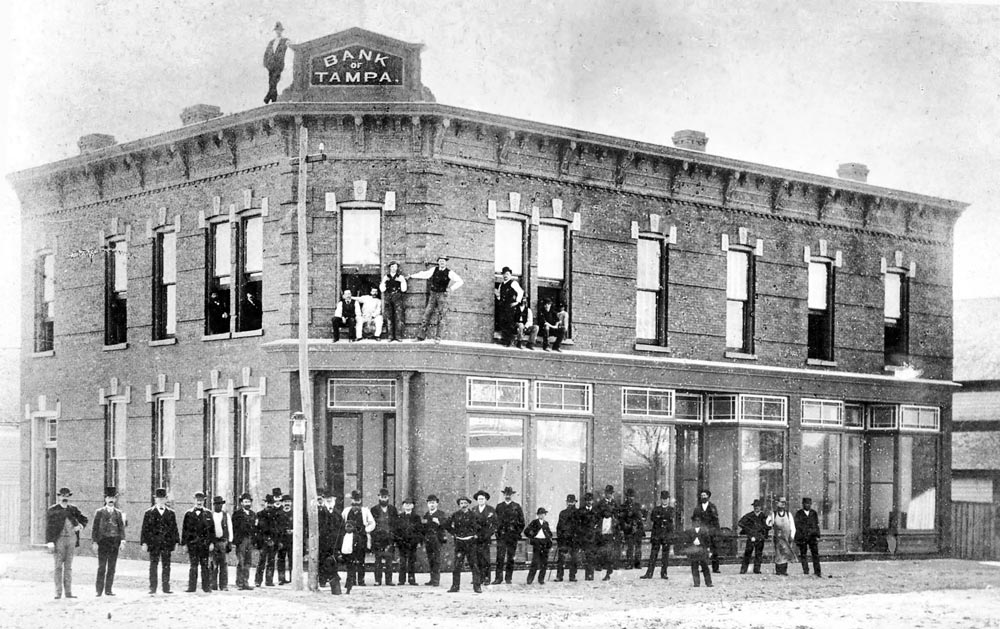

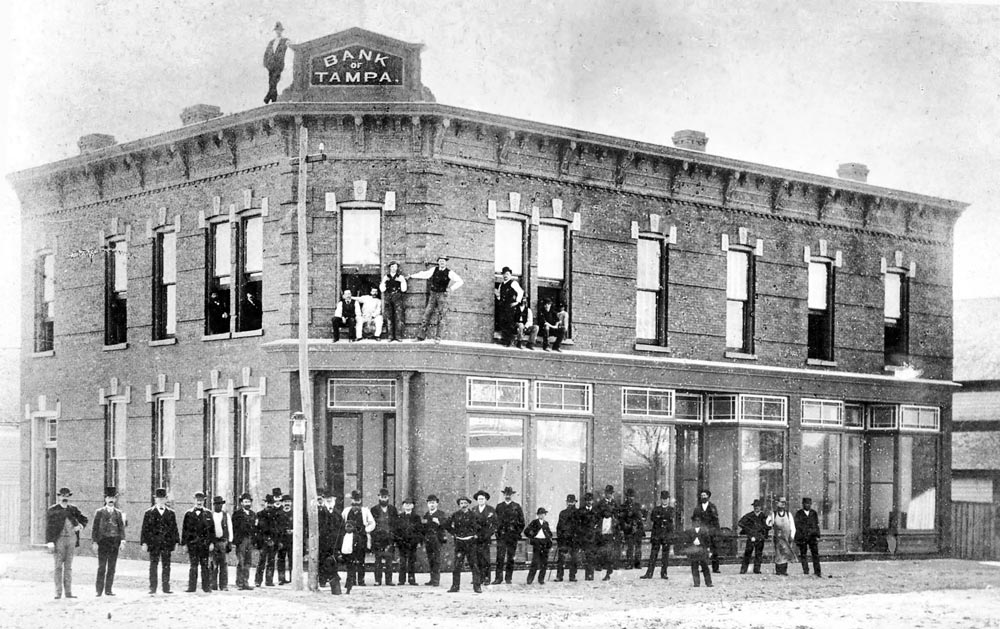

The First

National Bank first started as the Bank

of Tampa, seen below in 1886, it's

second building. It became First

National when it moved to their new

4-story building at 416 Franklin St. on

the southwest corner of Madison St.

around 1900.

Burgert Brothers photo courtesy of the

USF Library Digital Photo Collections

See the

image there uncropped; there is an

extremely large U.S. flag on an approx.

25 ft. tall flag pole

which can faintly be seen atop the

building.

|

|

The

Mugge Pumper

Immediately after this fire Wuerpel

and Tampa's leading citizens

convinced the town council that it

would be wise to invest in a fire

engine so a $600 "hand pumper" was

ordered. Paid for by successful

liquor dealer Robert Mugge, it

became known as the "Mugge Pumper."

It arrived July 30, 1886 along with

350 feet of two-inch hose and a hose

reel. Almost everyone in town

turned out the next day to see the

engine tested. The hose was run down

to the river and six of the

strongest firemen began laboring on

the pumps. The results were a

splendid-a stream of water which was

thrown clear over the top of John T.

Lesley's two story building at

Franklin and Washington.

Example of a hand-drawn pumper truck

which could be powered by six

firemen.

Image from "Hand Pumped Fire

Engines" by Flags Up at Pinterest

TAMPA FIRE COMPANY ORGANIZED,

Aug. 30, 1886

To make effective use of the new

equipment, the Tampa Fire Company

was on organized August 30, 1886,

with A. C. Wuerpel as president,

Robert Mugge as secretary, and

Herman Glogowski as treasurer.

Other members were G. B. Sparkman

(later the City of Tampa's first

mayor and judge of the circuit

court}, Odet Grillon, H. Hearquist,

C . O. Pinkert, John R. Jones, Leon

Dartize, Charles G. Lundgren, J. O.

Nelson, Vicente de Leo, and Ernest

Gerstenberger.

These men, and the members of the

Hook & Ladder Company, served

without pay. The new hand engine

and supply of hose did some good in

the fire of Sept. 1887.** But that

fire showed the necessity of a

reliable water supply and again the

council was receptive to equipping

the department as it stood at this

time.

**Allusion

to this fire comes from A.C.

Wuerpel's resignation letter of June

1890. "The council, then in charge

of the city's affairs, appreciated

the necessity of fire protection and

at my solicitation a hand engine and

supply of hose was provided, which

did good service in checking the

conflagration of September, 1887"

No other mention of this fire has

been found in any other available

resources. Although the images of

the four Tampa Weekly Journals for

September 1887 and the first one in

October are extremely faded and

almost completely illegible, enough

can be discerned to conclude that

the only fire mentioned was one in

Sanford, Fla. on Sept. 22nd.

During the next two years the fire

men did the best they could with the

hand pump engine. It served fairly

well when the fire was near the

river but was useless, of course, if

no adequate water supply was close

at hand. Many buildings burned to

the ground which could have been

saved if water had been available.

Everyone rejoiced, therefore, when

the waterworks company announced

that water soon would be turned into

the mains. |

|

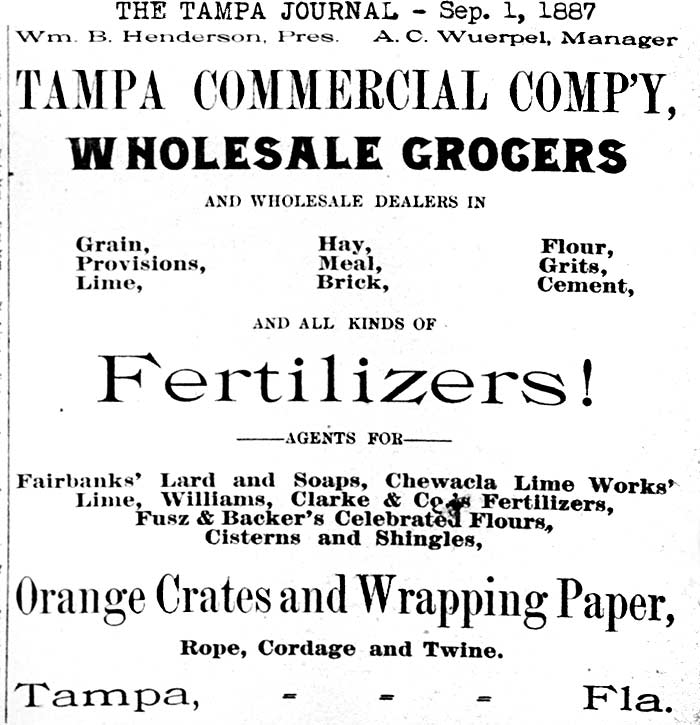

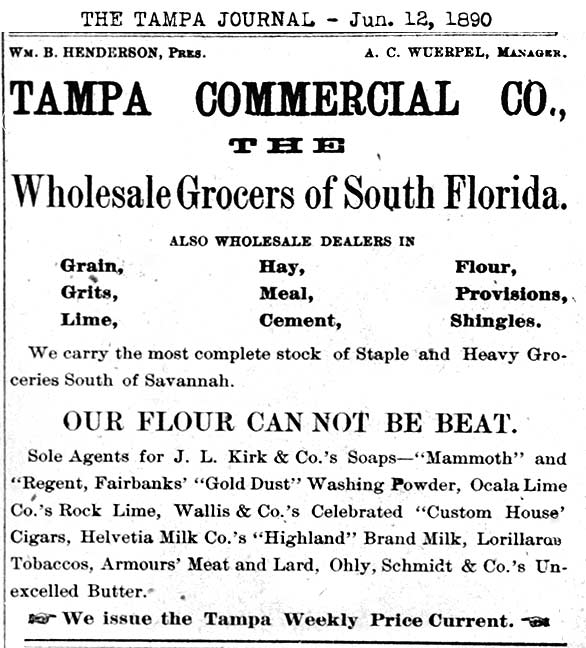

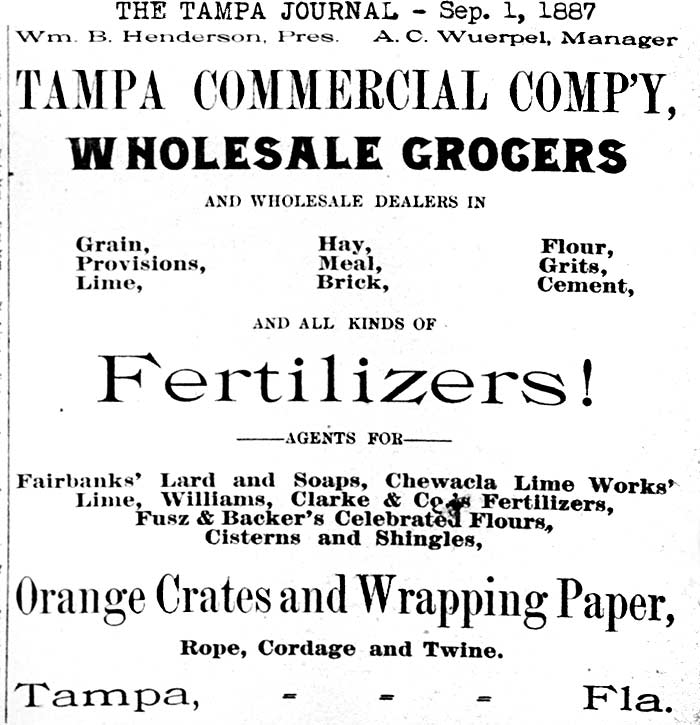

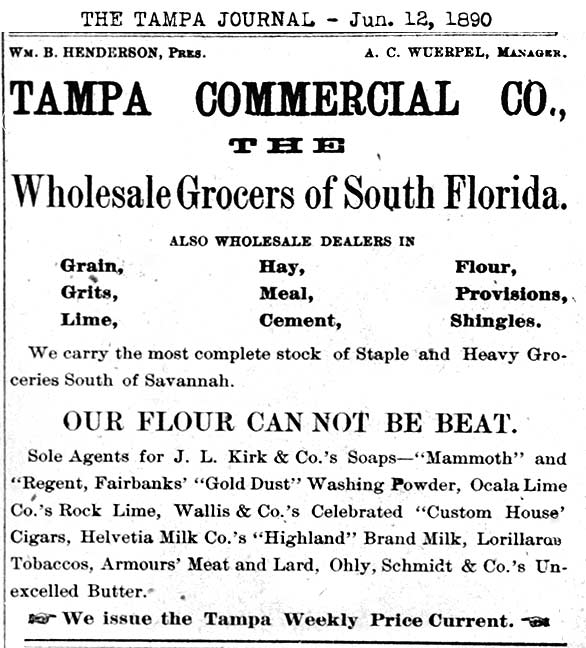

The first mention of A.C. Wuerpel in

Tampa newspapers is this Sep.1, 1887 ad

with Pres. Wm B. Henderson and A.C.

Wuerpel as manager of Tampa Commercial

Company Wholesale Grocers, one of the

businesses which demanded his time as he

alluded to in his resignation letter.

Ads for this company with him as manager

appeared almost daily in the Journal and

this was likely his main source of

income. The last ad to name him in this

position was published in the Tampa

Journal on June 25, 1891. |

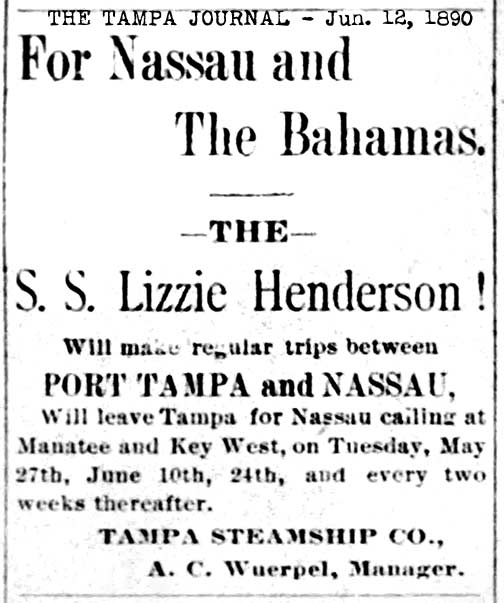

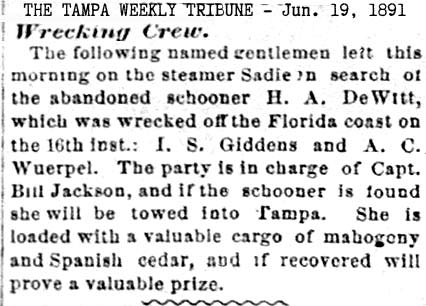

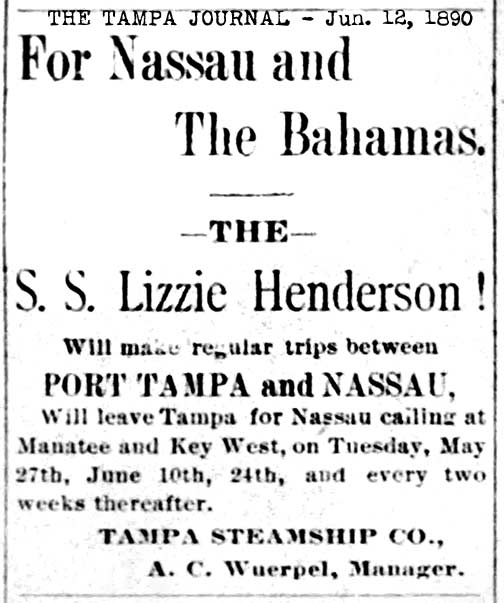

A. C. Wuerpel was also the manager of

this steamship company which was

probably another Wm. B. Henderson

business venture. |

|

|

|

|

|

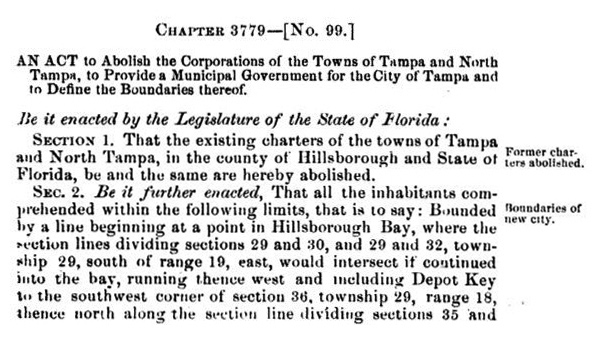

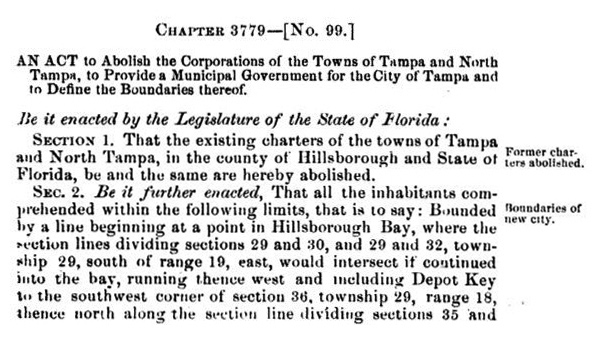

THE CITY

OF TAMPA ESTABLISHED - JUNE 2, 1887

The

City of Tampa was established on Jun 2,

1887 when under special act of the state

legislature, the Governor approved a

bill that granted the city of Tampa a

new charter, abolishing the town

governments of Tampa and North Tampa.

Section 5 of the charter provided for a

city-wide election for mayor, eleven

councilmen and other city officials, to

be held on the 2nd Tuesday in July. The

new charter also greatly expanded the

corporate limits of the city. Tampa now

took in North Tampa, Ybor City and some

land on the west side of the

Hillsborough River. The

City of Tampa was established on Jun 2,

1887 when under special act of the state

legislature, the Governor approved a

bill that granted the city of Tampa a

new charter, abolishing the town

governments of Tampa and North Tampa.

Section 5 of the charter provided for a

city-wide election for mayor, eleven

councilmen and other city officials, to

be held on the 2nd Tuesday in July. The

new charter also greatly expanded the

corporate limits of the city. Tampa now

took in North Tampa, Ybor City and some

land on the west side of the

Hillsborough River.

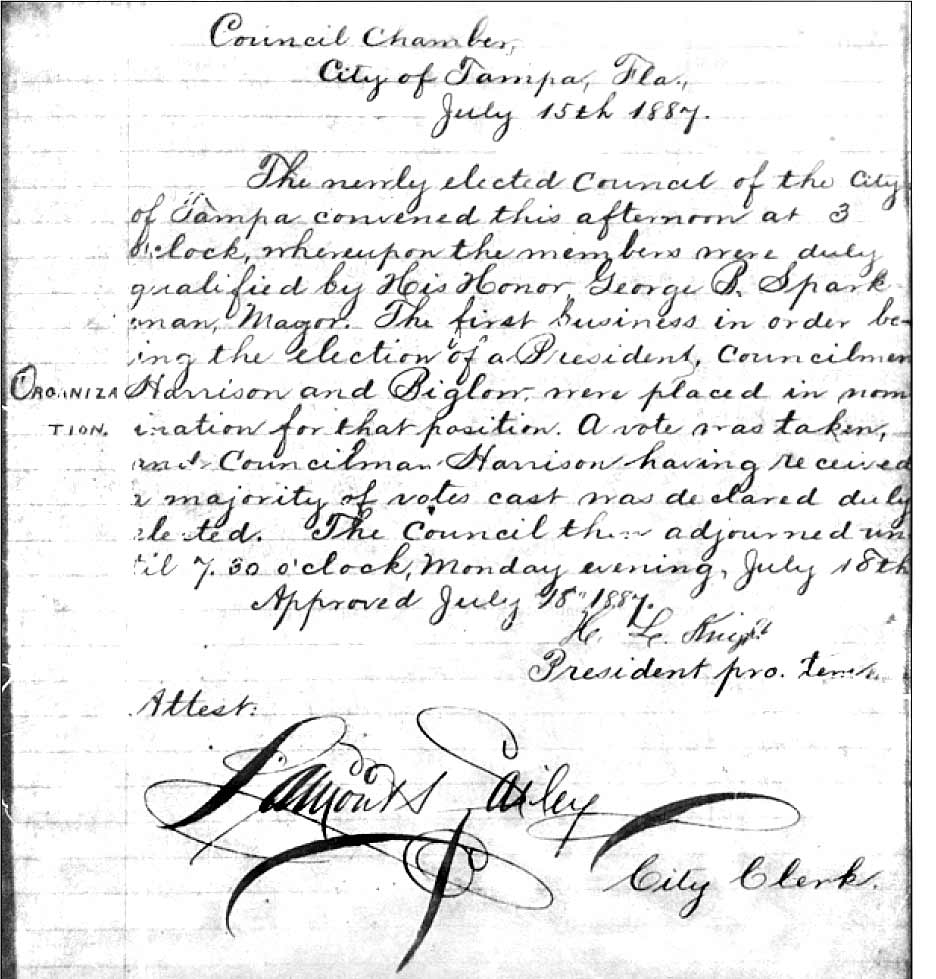

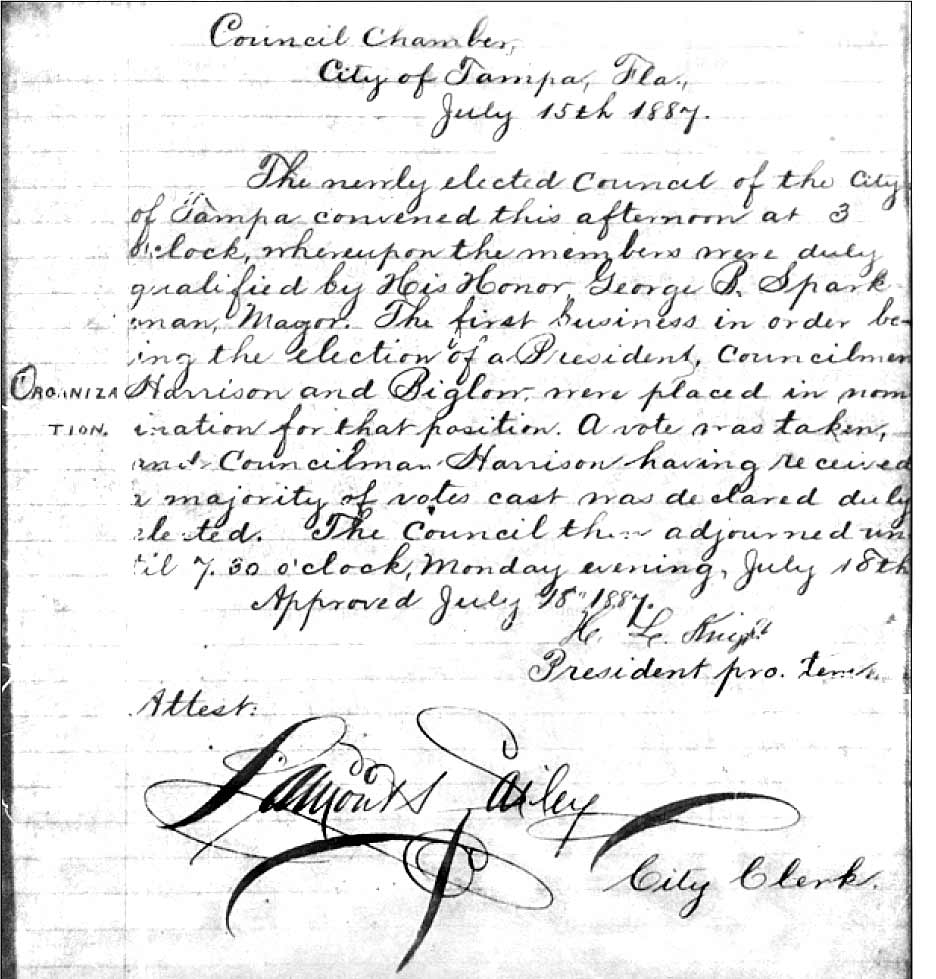

The

first city election under the new

charter was held July 12, 1887, and the

new mayor, Georg Bascom Sparkman, took

office on July 15, 1887, the date

considered to be when Tampa was

organized.

It was

a bitterly fought and controversial

election, accompanied by deplorable

behavior on the part of many Tampa

citizens.

City Clerk

Lamont Bailey's notes of the July 15,

1887 City Council meeting.

Image from THE

SUNLAND TRIBUNE, Journal of the

TAMPA HISTORICAL SOCIETY,

Volume VIII Number 1 November, 1982 - WHAT

HAPPENED IN TAMPA ON JULY 15, 1887 OR

THEREABOUTS by Joseph Hipp

Read more about this election and what

else was happening in Tampa at this time

here at TampaPix

|

This article is transcribed

here in its entirety due to

the poor quality of the

scanned image. |

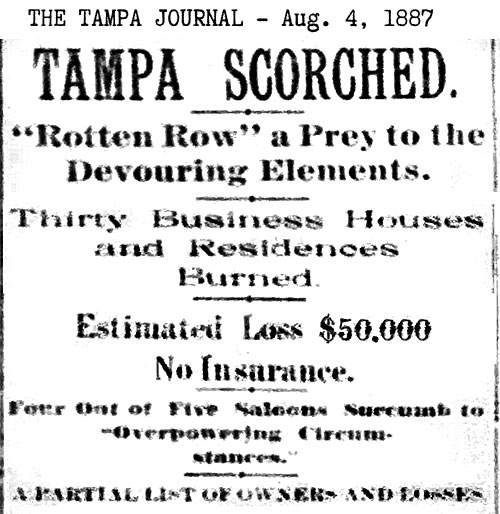

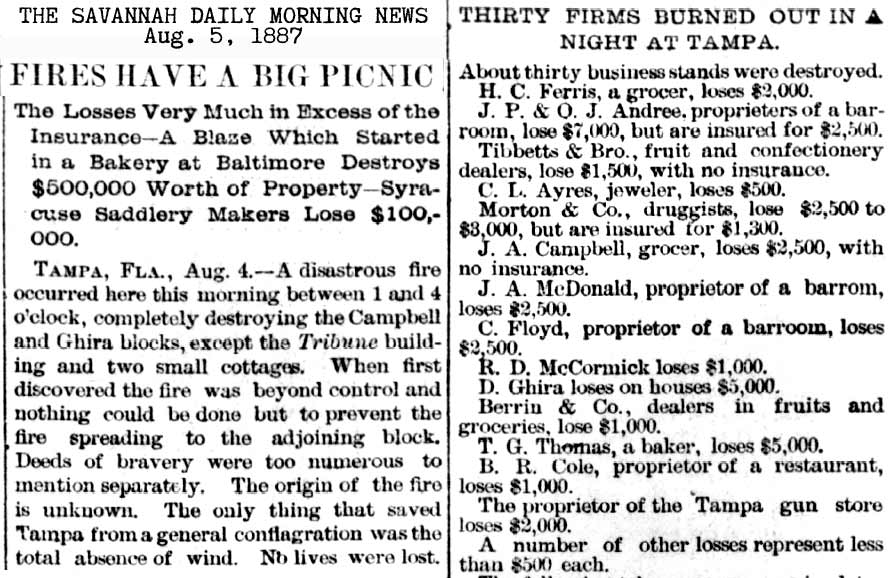

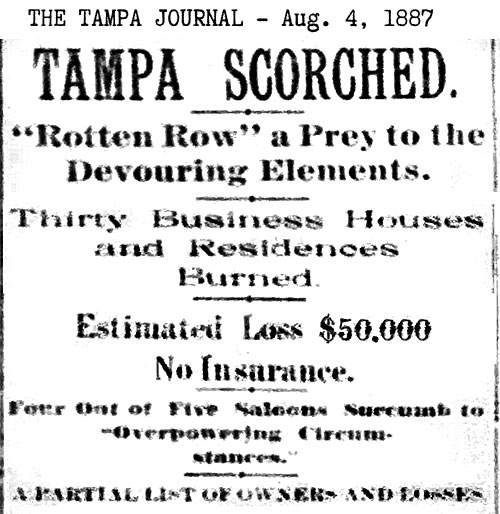

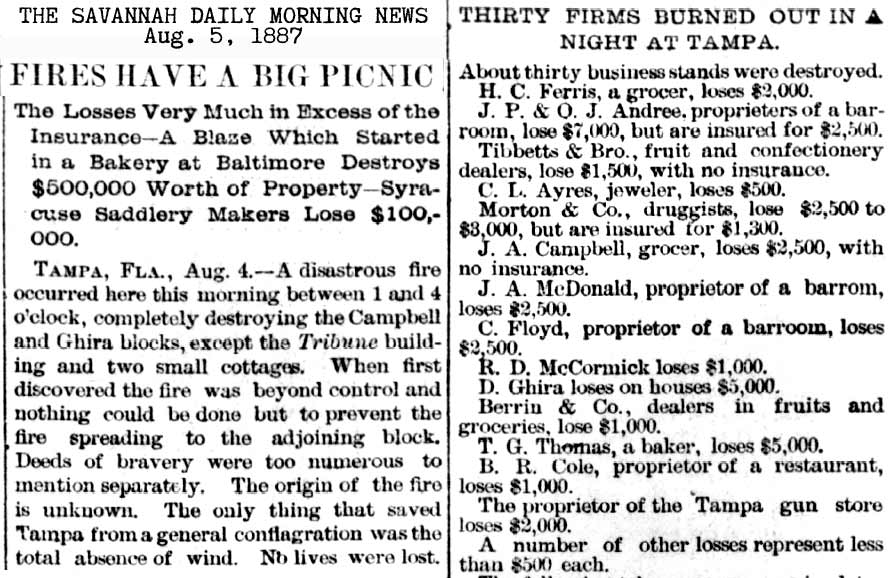

THE FIRE AT "ROTTEN ROW"

on Aug. 4, 1887

About two o’clock this

morning a fire broke out

near the center of what is

known as “Rotten Row,”

composed entirely of one and

two story wooden buildings,

and occupied mostly by small

tradesmen such as fruit

stalls, retail groceries,

barber shops, etc. on one

side of the street, and

principally by saloons on

the the other. The fire

seems to have originated

either in Cole’s restaurant

or Thomas’ barber shop, the

flames spreading rapidly

each way from the starting

point and soon enveloping

the entire block in flames.

It was some time before any

kind of effort could be made

to control the fire, and for

a time it looked as though

the whole business part of

the city must surely go, and

the absence of any wind was

probably what saved the best

portion of it. The fire

department, however, soon

got down to business, and by

the almost superhuman

efforts of the firemen the

flames were prevented from

being communicated to the

buildings across Lafayette

street, extending north,

thus saving the Opera house,

Gunn & Seckinger’s large

grocery store and other

valuable business blocks. It

was the prevailing opinion

that nothing could be done

to save the buildings on

either side of Franklin

street between Lafayette and

the ditch, and all the

efforts of the firemen were

directed to preventing the

spread of the flames to the

adjoining blocks, and that

they were successful in this

measure was certainly not

due to the completeness of

our water works system, but

to the untiring efforts of

the people. |

|

The old hand engine did good

service as long as water

could be had, when bucket

brigades were formed and the

sides of the buildings kept

thoroughly drenched. By 4:30

o’clock the two blocks above

mentioned were burned to the

ground, very little of the

contents being saved,

although the utmost good

will prevailed, and

everybody did what they

could to assist their more

unfortunate neighbors.

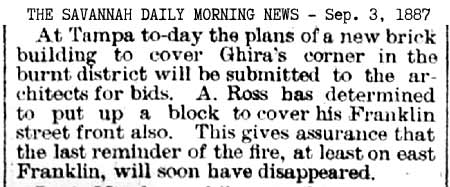

THE FIRE

The Journal deeply

sympathizes with all who

lost their property in last

night’s conflagration. But

aside from the hardship

entailed upon those who

directly suffered loss, the

effect upon the city can not

fail to be otherwise than

beneficial. Two of the

finest business blocks in

the city are now open for

substantial and valuable

improvement. The real value

of these blocks this morning

is greater than it was

yesterday; and we believe

that within one year from

this date, instead of the

former shanties that stood

yesterday as an eyesore to

the citizens of Tampa, will

tower magnificent brick

blocks.

Read more about this fire at

TampaPix's feature, The

2nd Lafayette St. Bridge.

|

Place your cursor on the map

to see it in 1889

LAFAYETTE ST.

JACKSON ST

|

|

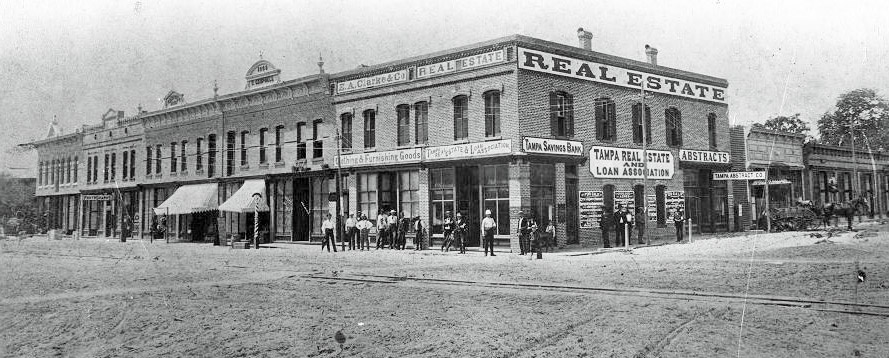

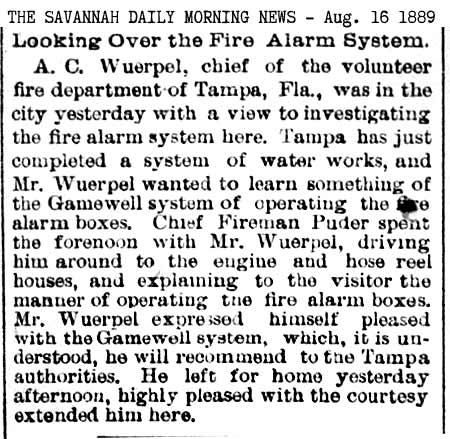

Articles from the Digital

Library of Georgia -

Historic Newspapers |

|

|

|

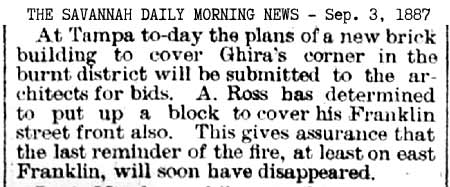

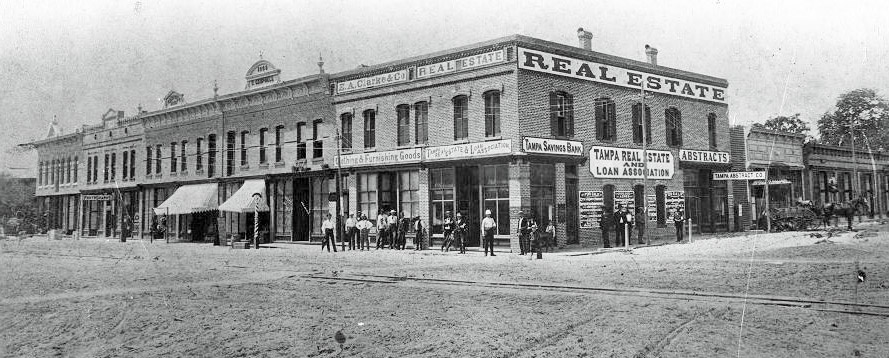

BELOW: The Tampa

Savings Bank at

Tibbetts Corner

in 1888-89,

looking

southwest from

the intersection

of Franklin St.

(on left) and

Lafayette (on

right).

Notice the

barber pole on

the street, left

of center of

photo. The

Tibbetts

confectionery is

where the awning

is just left of

the pole.

|

On the 1889 map

above, this was

the west side

(left side) of

Franklin St. at

Lafayette with

Tibbetts and the

barber shop

outlined in

yellow.

Burgert

Bros. photo

below courtesy of the USF Library

digital

collection. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THE NEW

CITY OF TAMPA IS DIVIDED INTO FOUR WARDS

One of

the first acts of the new Tampa city

government was the passage of an

ordinance on September 6, 1887 dividing

the city into four wards. The old town

of Tampa became the First Ward, North

Tampa the Second Ward, West Tampa the

Third Ward, and Ybor City the Fourth

Ward. Ybor City agreed to enter the city

on the strength of promises that Tampa

soon would get a water system, an

organized fire department, electric

lights and paved streets.

Preparations for drilling artesian wells

were starting late in the summer 1887.

On September 13, the new city council

awarded a water works franchise to the

Jeter-Boardman Waterworks Company and

agreed to pay $4,500 a year for 110

hydrants. But action on these

improvements and many others was delayed

by one of the worst calamities which

ever befell the city.

|

|

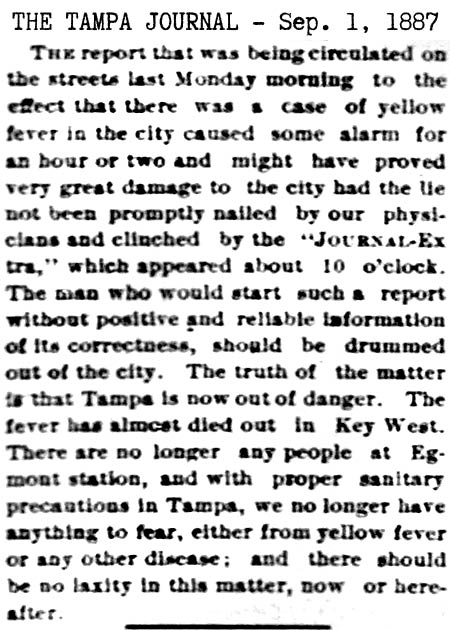

YELLOW FEVER EPIDEMIC IN

TAMPA

Below is from the

University of South Florida

Library 500

Years of Discovering

Florida, 1887 Epidemic in

Tampa, and “A

SNEAKY, COWARDLY ENEMY”

TAMPA’S YELLOW FEVER

EPIDEMIC OF 1887-88 by

Eirlys Barker, and various

newspaper articles from the

period.

Tampa was relatively free of

Yellow Fever from 1871 to

1886, so Tampans were lulled

into the notion that another

large outbreak would not

happen in their city.

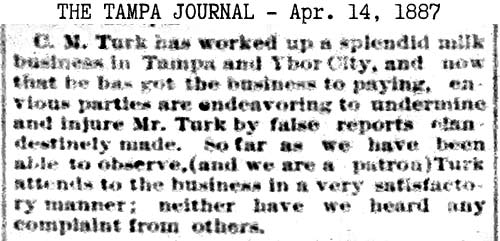

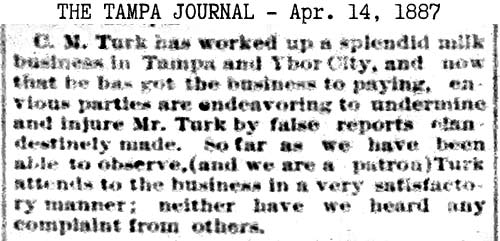

However, Charlie Turk of

Ybor City had the dubious

distinction of being the

first person in Tampa to die

of “yellow jack” in 1887.

An alleged fruit smuggler,

he managed a barber shop.

His family contended that he

had contracted the disease

by using a blanket belonging

to an Italian fruit dealer

named Pepe. Pepe, it was

said, had fallen ill with

strange symptoms, but had

recovered and mysteriously

disappeared. While Turk was

still lying ill in Ybor

City, the first case within

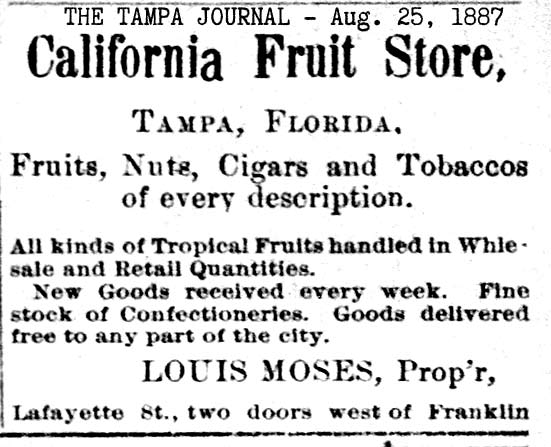

Tampa proper occurred on

September 16, when a second

Italian fruit dealer, Louis

Moses, took sick. Other

Italian traders soon

followed. Possibly six

Italians contracted yellow

fever, as did a few of their

American customers.

These fruit dealers traded

with citizens from Cuba. The

cargoes of fruit from Cuba

most likely were the

carriers of the infected

Aedes Aegypti mosquitoes.

When the Cubans traded with

the Italians, the infected

mosquito was able to bite

the Tampan man, which led to

the subsequent epidemic.

Turk died in late September;

however physicians were

hesitant to call it Yellow

Fever.

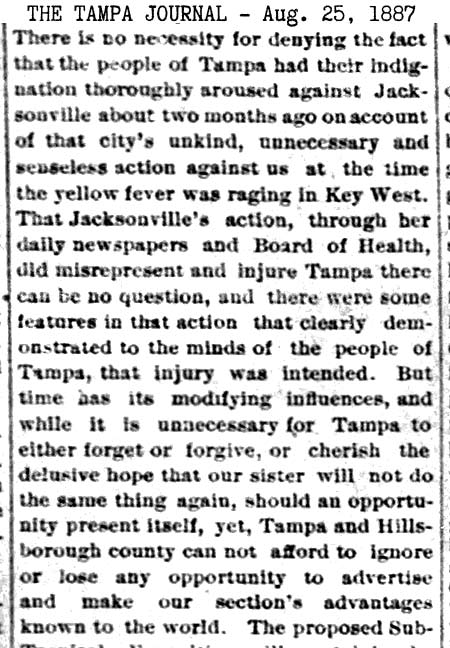

Leading

citizens considered it an

over-reaction to the

situation when Jacksonville

inflicted a quarantine on

all people from Tampa. This

action was protested by the

editor of the Tampa Weekly

Journal, Harvey Cooper, who

claimed that it hurt the

“Hotel Interest.” Cooper

seemed especially concerned

about Henry Plant’s plans

for building a magnificent

hotel at Tampa to attract

thousands of tourists--and

millions of dollars--every

winter. In defense of

this vision, Cooper

sarcastically reported that

the city was no longer in a

state of panic, and “the

people are laughing at their

own foolishness...Only one

death in Tampa since--the

Lord only knows when, and

that occurred last Sunday.

It was a mule. It would be

dangerous for Jacksonville

to lift their quarantine

against Tampa yet awhile." Leading

citizens considered it an

over-reaction to the

situation when Jacksonville

inflicted a quarantine on

all people from Tampa. This

action was protested by the

editor of the Tampa Weekly

Journal, Harvey Cooper, who

claimed that it hurt the

“Hotel Interest.” Cooper

seemed especially concerned

about Henry Plant’s plans

for building a magnificent

hotel at Tampa to attract

thousands of tourists--and

millions of dollars--every

winter. In defense of

this vision, Cooper

sarcastically reported that

the city was no longer in a

state of panic, and “the

people are laughing at their

own foolishness...Only one

death in Tampa since--the

Lord only knows when, and

that occurred last Sunday.

It was a mule. It would be

dangerous for Jacksonville

to lift their quarantine

against Tampa yet awhile."

Dr. Wall was out of town

when Turk and Moses had

become sick. When the

physician returned on

the twenty-fifth, the

town was seething with

rumors of the scourge’s

presence. Wall

immediately suspected

the worst.

By

September 29, Wall had seen

five suspicious cases,

including two that other

physicians had diagnosed as

bilious remittent fever.

However, he deemed it

“prudent to await further

developments,” for “it is a

very serious thing to

announce the presence of

yellow fever.” Of the

suspicious cases in

September, only Turk’s had

been fatal which suggested

that dengue--a non-fatal

disease with symptoms

similar to yellow

fever--might have been the

cause. Therefore, Wall

continued to observe

possible cases, and he did

not make the fateful

declaration until all his

doubts had disappeared. By

September 29, Wall had seen

five suspicious cases,

including two that other

physicians had diagnosed as

bilious remittent fever.

However, he deemed it

“prudent to await further

developments,” for “it is a

very serious thing to

announce the presence of

yellow fever.” Of the

suspicious cases in

September, only Turk’s had

been fatal which suggested

that dengue--a non-fatal

disease with symptoms

similar to yellow

fever--might have been the

cause. Therefore, Wall

continued to observe

possible cases, and he did

not make the fateful

declaration until all his

doubts had disappeared.

|

|

|

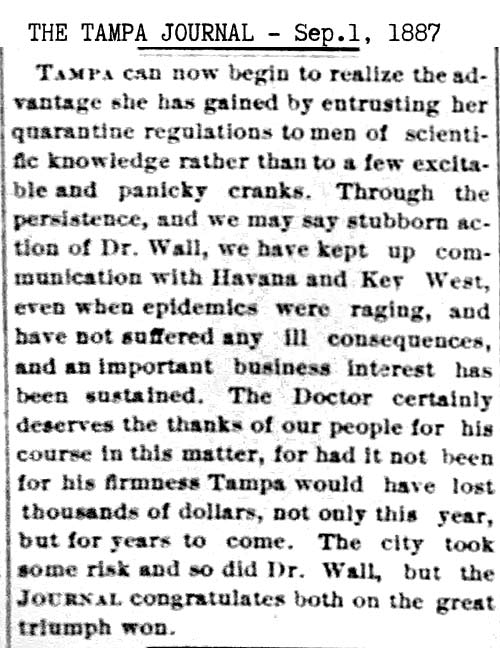

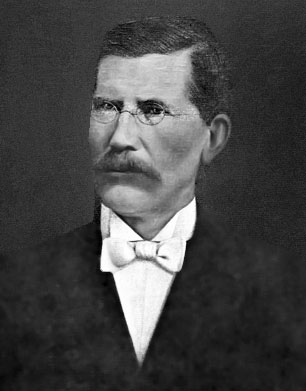

Dr.

John P.

Wall,

Tampa's 16th

mayor

1878 to 1880 |

That point was reached on

Oct. 4, by which time Dr.

Wall had seen a total of

seven cases. Two patients

had died, and albumin was in

the urine of two other

cases. Summoning the board

of health, Wall announced

his diagnosis. He noted that

this was received “with many

objections, on the part of

the other members, on the

ground that the city was

very healthy, hardly anybody

was sick, and that very few

deaths had occurred,

certainly not as many as

might be expected in so

large a population.” Wall

conceded that there was no

epidemic yet, but he hoped

to avoid one by depopulating

the city and by urging all

non-immunes to flee. He

wanted this implemented

before the news leaked out

by wire, so that those

leaving would not be denied

refuge everywhere they went.

The Yellow Fever epidemic is

continued after the electric

lighting of Tampa below.

|

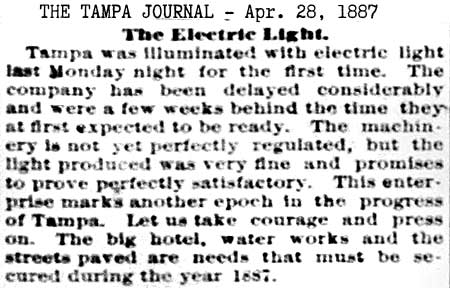

TAMPA INTRODUCED

TO ELECTRIC

LIGHTING - The

Tampa Journal -

Jan. 5, 1887 - The

lengthy article

begins in all

caps:

UPWARD AND

ONWARD WE

MOVE!

ELECTRIC

LIGHTS TO BE

PUT IN THE

CITY AT

ONCE. THE

WATER-WORKS

AND HOTEL

SOON TO

FOLLOW, AND

OUR CITY BY

THE SEA TO

TAKE HER

PLACE AMONG

THE FIRST OF

THE STATE.

Steps have been

taken to install

an Electric

Machine in Tampa

with enough

power to meet

all of Tampa's

present needs

for more and

better light.

F. B. Pickering

had come to

Tampa from

Jacksonville,

representing

several

prominent

electric light

companies in the

country. He was

displaying

incandescent

lighting and

various sources

of power in

order to induce

citizens to form

a joint stock

company to put

an electric

plant in Tampa.

His main

obstacle was

finding a

suitable engine

to run the

little dynamo he

carried with

him. His first

attempt was to

light the store

of Herman

Glogowski, but

lack of steam

power on his

first try was

not satisfactory

to him, but it

did convince

witnesses that

there was merit

in the machine

he was showing.

Pickering then

made arrangement

to use an engine

in a local

machine shop, so

moved his

display there.

When all was

ready, he

invited

prominent

citizens and

members of the

City Council to

see the light

made with

increased

power. The

witnesses were

"exceedingly

pleased and

pronounced it

very fine

indeed, but

unfortunately,

only a few

persons saw

it." So

Pickering found

it difficult to

organize a

stockholding

company.

He then became

discouraged and

went to Ybor

City to try to

convince Mr.

Ybor and others

to install an

electric plant

there.

Introduced to

Mr. Manrara by

the author of

the article, he

explained the

workings, cost,

etc, of the

system. Not

having been at

the Tampa

demonstration,

the author was

convinced of the

process and

invited

Pickering to

meet with Capt

John T Lesley,

Robert Jackson,

and the Tampa

Journal editor,

W. N. Conoley,

the next

morning. After

hearing his

presentation,

the men said

that if he could

make a

satisfactory

display of the

light to them,

they would be

prepared to

close a contract

with him for a

plant in Tampa.

This one done

and at once an

agreement was

made between

Lesley, Jackson

and Conoley, and

Pickering to put

in a FIVE

HUNDRED

INCANDESCENT

LIGHT MACHINE OF

THE WESTINGHOUSE

PATENT &

MANUFACTURER,

AND A

THIRTY-FIVE ARC

LIGHT MACHINE of

the American

Company's

manufacture,

(Fuller-Wood

patent).

[Read about "The

War of the

Currents,"

the battle

between Thomas

Edison,

proponent of

Direct Current,

and George

Westinghouse,

proponent of

Alternating

Current, and the

role that

inventor Nikola

Tesla played for

both men, at

Smithsonian.com.

From the

article: Both

men knew there

was room for but

one American

electricity

system, and

Edison set out

to ruin

Westinghouse in

“a great

political, legal

and marketing

game” that saw

the famous

inventor stage

publicity events

where dogs,

horses and even

an elephant were

killed using

Westinghouse’s

alternating

current. The two

men would play

out their battle

on the front

pages of

newspapers and

in the Supreme

Court, in the

country’s first

attempt to

execute a human

being with

electricity. ]

Mr. Pickering

then left for

Pittsburgh to

buy all the

machinery

necessary. A

partial canvass

of the city

indicated that

all the lights

would be spoken

for soon after

the plant was in

operation and

expectations

were that within

the next 40 days

everything would

be set up and in

operation. They

hoped that the

City Council

would make a

contract for

lighting as up

until this

point, no effort

had been made.

"It will not

only lessen the

cost of

insurance for

all those who

use it, but will

give us the best

lighted place

south of

Jacksonville,

and puts Tampa

at once among

the progressive

places of our

now

rapidly-progressing

state.

After the

lighting of

Tampa, efforts

would turn to

"the Grand

Hotel". "With

any determined

and united

effort, we can

build a house

second to none

in Florida. Why

not do it and do

it at once?"

The lights and

hotel would

bring the

necessity of a

water works, and

with these three

factors in the

make up of a

live and

progressive

city, we will

have reached a

tone and dignity

that will make

some of our

sister cities

wince. Let

every one be up

and at work for

to-day is

Tampa's

opportunity.

Let no man say

"We can't." See

the entire

article here,

click the image

again to see it

full size.

In the midst of

the Yellow Fever

epidemic, the

City of Tampa

began converting

from kerosene

street lamps to

electric. Below

from "Tampa

Early Lighting

and

Transportation,

by Arsenio M.

Sanchez, THE

SUNLAND TRIBUNE

Volume XVII

November, 1991

Journal of the

TAMPA HISTORICAL

SOCIETY.

|

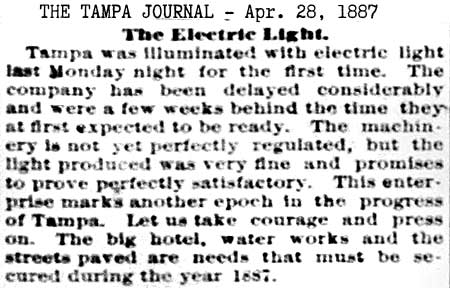

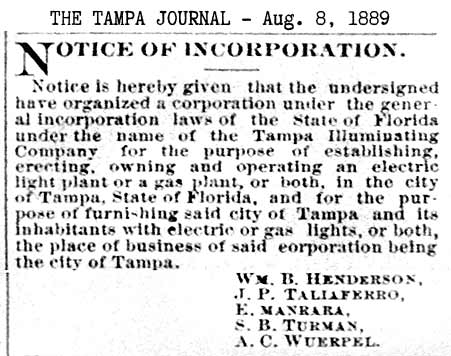

An

early

Tampa

Electric

Company

(not

the

present

Co.)

was

organized

in

Tampa

on

January

29,

1887.

About

three

months

later

the

company

brought

the

first

Electric

lights

to

the

city

of

Tampa.

A

small

Westinghouse

generator

was

brought

in

and

two

arc

lights

were

erected,

one

at

the

corner

of

Franklin

and

Washington

Streets;

and

one

in

front

of

the

brand

new

"Dry

Goods

Palace."

Tampa’s

first

"light

show"

took

place

Monday,

April

28,

1887.**

Word

got

around

and

people

came

from

all

parts

of

town

to

witness

the

event.

The

Tampa

Journal

recorded

the

occasion

by

saying,

"The

amazed

throng

could

hardly

believe

that

the

stygian

darkness

could

be

dispelled

so

miraculously

by

current

coming

through

a

wire.

Dazzling

bright

though

these

arc

lights

were,

they

were

at

best

a

qualified

success,

sputtering,

crackling

and

hissing,

they

went

out

with

dismaying

frequency.

**The

date

given

by

Mr.

Sanchez

was

actually

the

date

of

the

Tampa

Journal

article,

which

below

can

be

seen

that

the

date

of

the

lighting,

"last

Monday

night"

would

have

been

April

25th. |

|

|

The

above

reference

to

"the

big

hotel"

was

H.

B.

Plant's

Tampa

Bay

Hotel. |

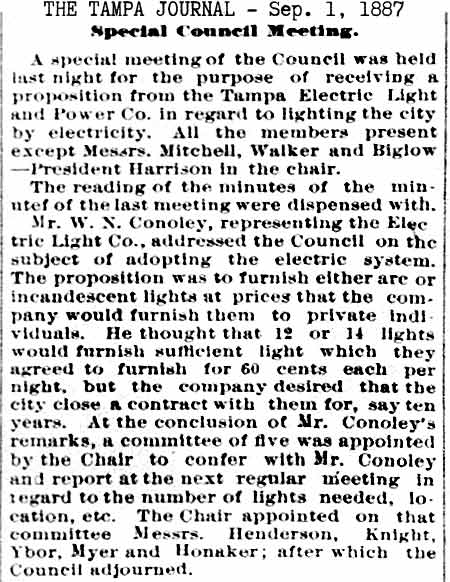

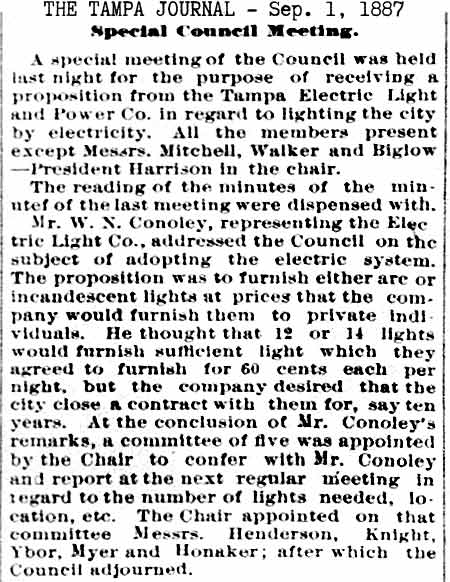

FIRST LIGHTING

CONTRACT

At a special

City Council

meeting on Aug.

31, 1887, W. N.

Conoley of Tampa

Electric Light &

Power presented

his proposal to

those present.

The proposal was

for arc or

incandescent

lighting at the

same price they

would offer to

private

citizens. He

proposed 12 to

14 lights at a

rate of 60 cents

per night under

the stipulation

that the city

would enter into

a 10-year

contract with

him.

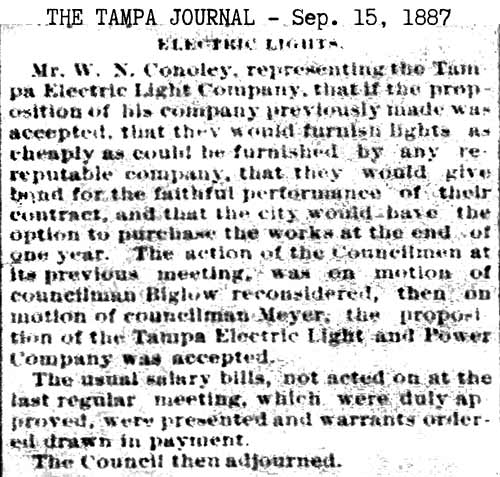

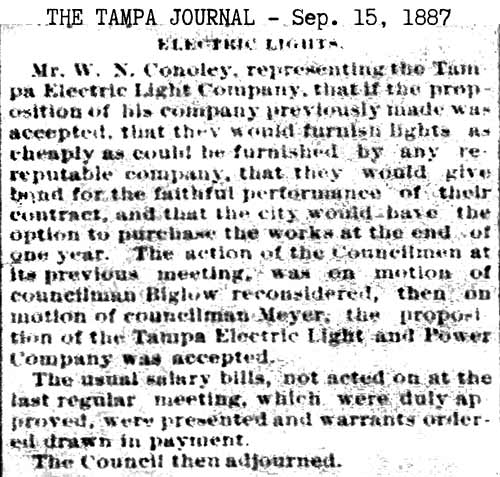

Judging from

what they saw,

the City fathers

on Sept. 13,

1887 met with

the City Council

and awarded the

fledgling

company a

ten-year

contract to

provide street

lighting. Twelve

arc lights at 60

cents a night to

be provided.

|

|

|

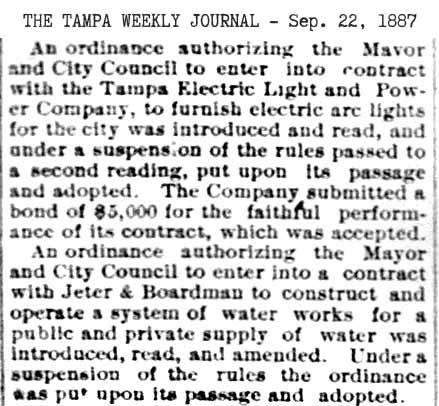

The city council

accepted the

offer by Tampa

Electric Light

Co. to furnish

the city with

electric street

lamps. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

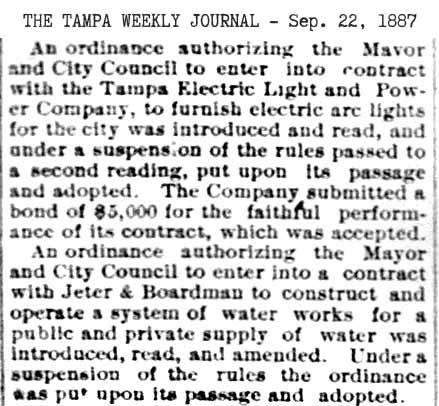

On Sep. 22,

1887, the City

Council passed

an ordinance

allowing Tampa

Electric Light &

Power to

contract with

the City of

Tampa. |

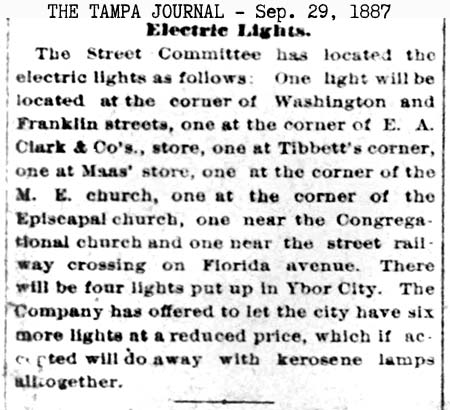

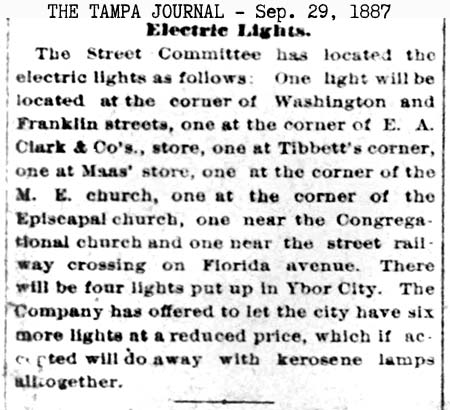

Sep. 29, 1887 -

The Street

Committee

announced the

locations of

eight new street

lights. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In the end, Wall prevailed.

On October 5, he began

spreading the news to local

citizens, while the board of

health went beyond his

suggestions and declared

that epidemic proportions

had already been reached. A

few of Tampa’s citizens had

fled even before this date.

On October 4, a Jacksonville

paper reported that a

refugee from Tampa died at

Palatka and around one

hundred of Palatka’s

citizens had, in turn, fled

from that City. Fear, it

seems, was as contagious as

yellow fever.

This news incited panic in

people which caused many to

flee Tampa. Since a person

who is infected with the

illness does not immediately

know they are sick, it was

very easy for the illness to

spread to other cities in

Florida. While some people

did flee the city, many

others decided that it would

be better to stay put. From

the remaining Tampans, many

of them kept diary entries

of their experiences with

Yellow Fever. In the diary

of E.E. and E.B. Johnson,

one can read about a man who

loses his father to the

disease coupled with the

writer himself contracting

the dreaded disease.

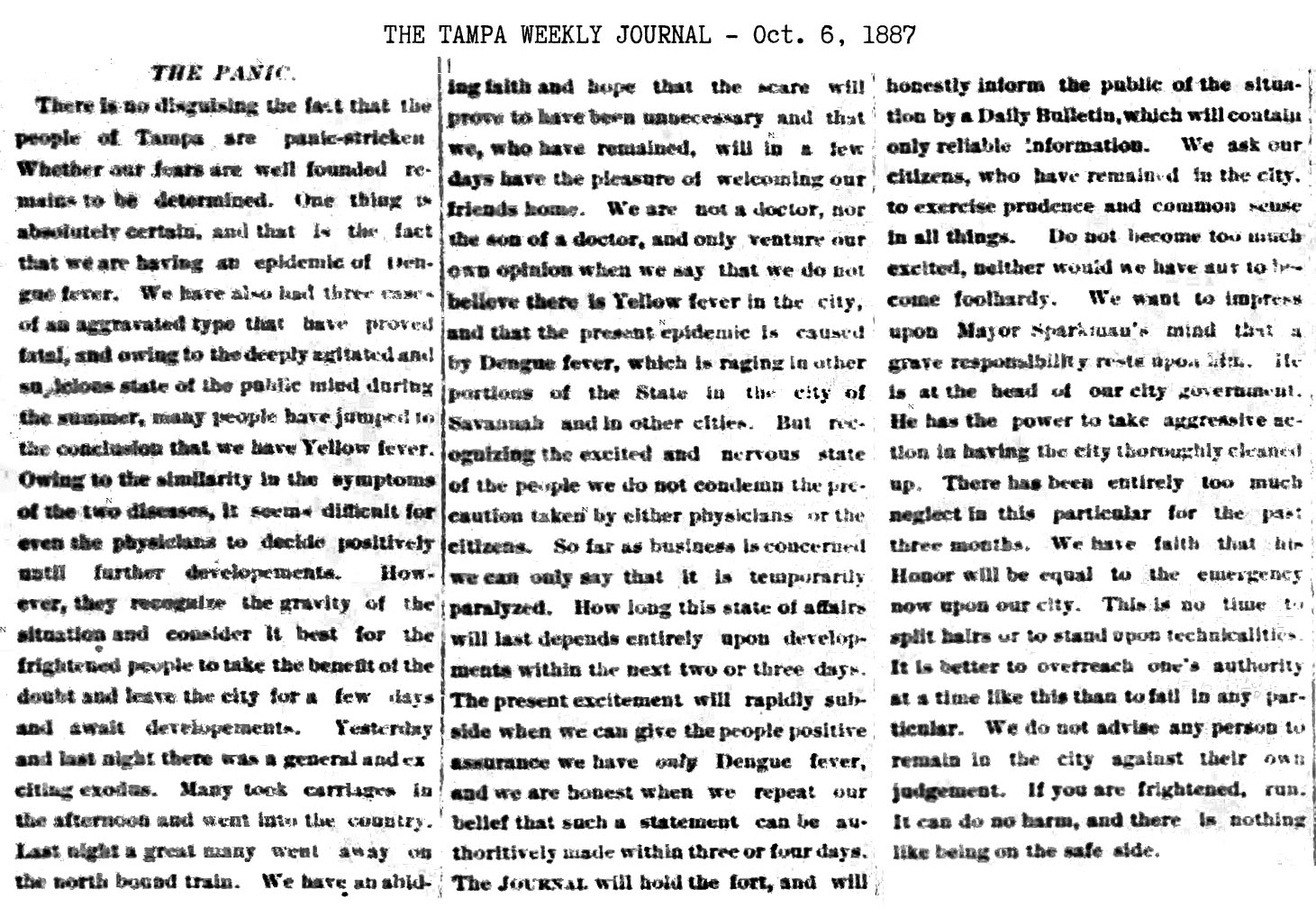

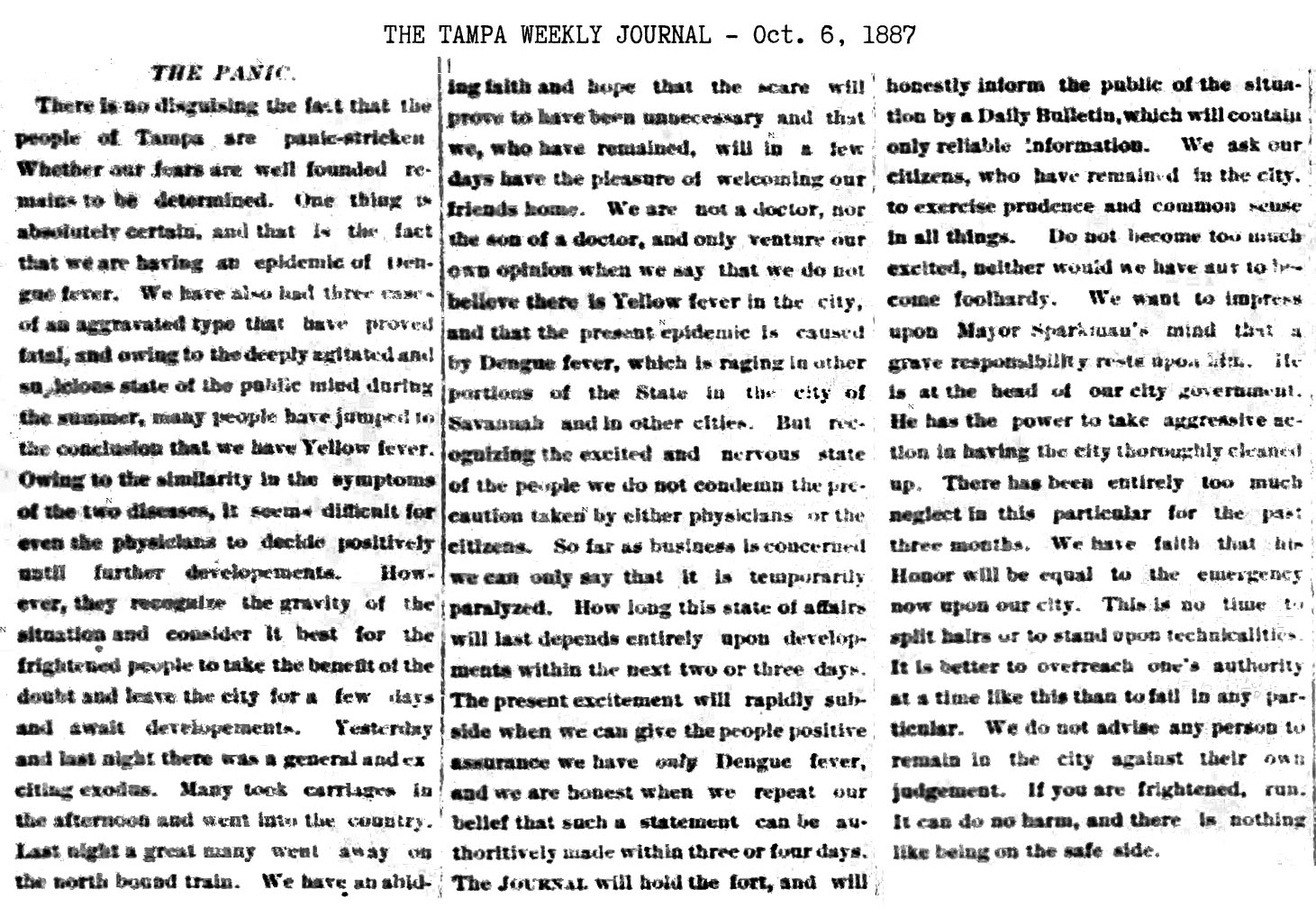

On October 6, 1887, the

Tampa Journal admitted that

panic gripped the city.

“There is no use disguising

the fact that the people of

Tampa are panic stricken,”

the Journal observed.

“Whether our fears are

well-founded remains to be

determined.” The newspaper

mentioned the “general and

exciting exodus” and

reported that scores of

people had left on the

northbound train the

previous evening. However,

the Journal tried to

minimize the threat by

stating “the fact that we

are having an epidemic of

Dengue fever.” Conceding

that “three cases of an

aggravated type. . . have

proved fatal,” the paper

declared that “many people

have jumped to the

conclusion that we have

Yellow fever.”

The Journal emphasized that

dengue was raging throughout

Florida and in Savannah,

implying yet again that

Tampa’s epidemic was due to

the milder, less feared

disease. “Do not become too

much excited,” the editor

advised residents who had

not fled, but he added: “If

you are frightened, run. It

can do no harm, and there is

nothing like being on the

safe side.”

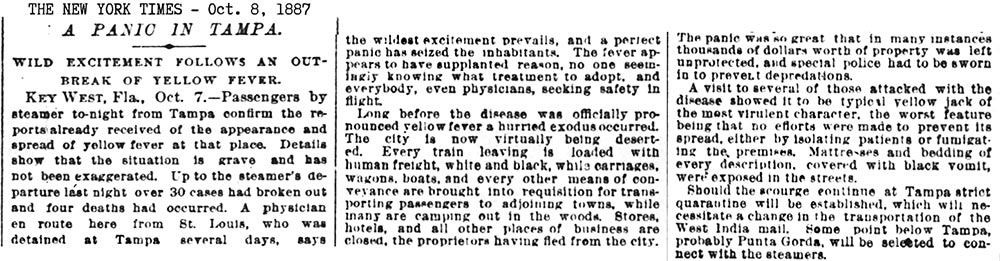

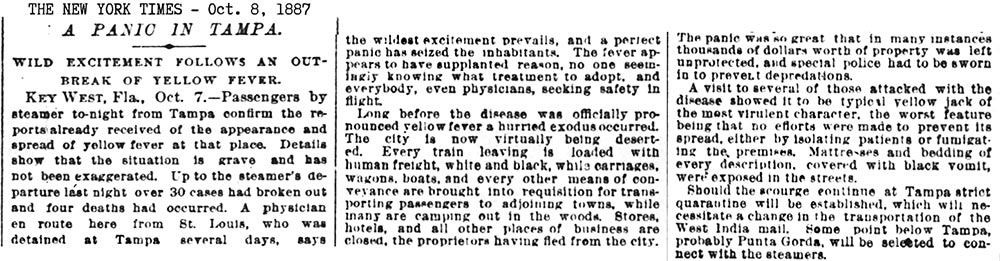

On October 8, Tampa’s

epidemic made the front page

of the New York Times.

Noting the “wild excitement”

in the city, the Times did

not doubt that the disease

was yellow fever. “The fever

seems to have supplanted

reason, no one seemingly

knowing what treatment to

adopt, and everyone, even

physicians, seeking safety

in flight,” the Times

reported. “The city is now

virtually deserted. . .The

panic was so great, that, in

many instances, thousands of

dollars worth of property

was left unprotected.”

|

|

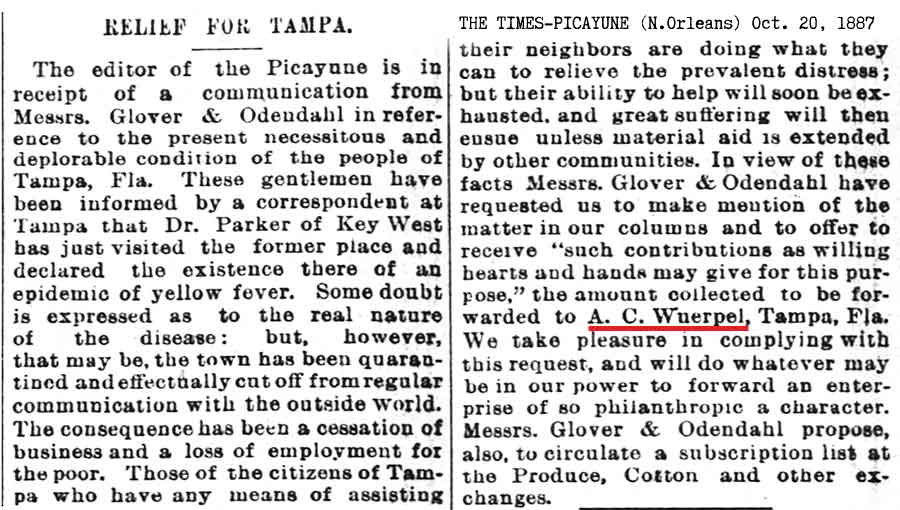

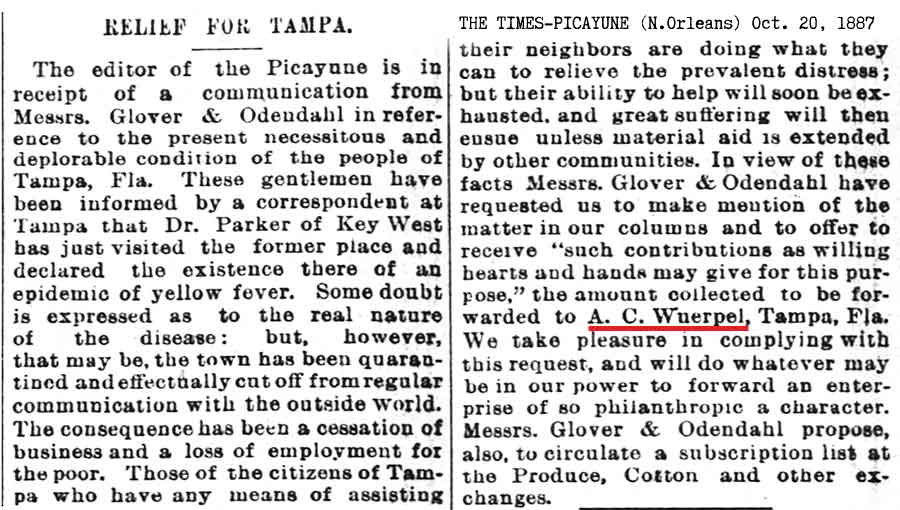

The Oct. 20,

1887 article

below says Tampa

was visited by a

Key West doctor

who confirms a

Yellow Fever

epidemic in

Tampa. The city

has been

quarantined thus

causing a great

loss of business

and employment.

They solicit

material support

from the people

and businesses

of New Orleans,

to be sent to

A.C. Wuerpel in

Tampa. |

|

|

|

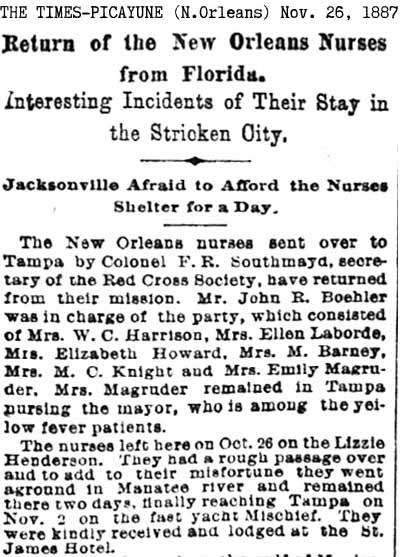

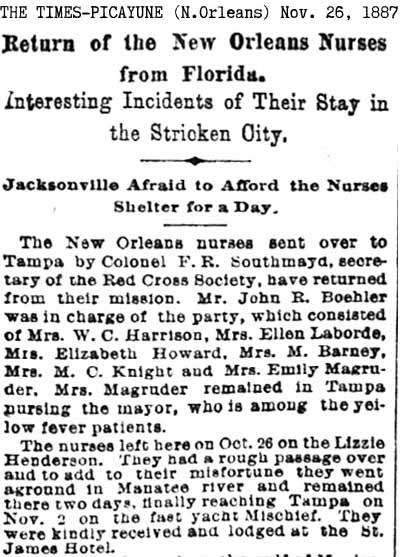

The Nov. 26,

1887 article at

above right

tells of Red

Cross nurses

that were sent

to Tampa are

leaving by way

of Jacksonville.

It also tells of

the quarantine

surrounding

Tampa being

enforced by men

with shotguns.

Also included is

a letter

received from

Hugh

Macfarlane. See

the whole

article with

more info and

details..

When the image

opens, click it

again to see it

full size. |

|

Altogether, in the year 1887 it is

estimated by Dr. John P. Wall that there

were about 1000 cases of Yellow Fever in

Tampa with about 100 deaths, however it

is now thought that this number could be

grossly underestimated. Dr. Wall's

intensive study of the disease had led

him to conclude in 1873 that the cause

was the tree-top mosquito. His findings

were ignored and ridiculed by proponents

of filth being the cause. Dr. Wall

apparently did not pursue the

mosquito-borne explanation diligently

and so publically, he appears to have

gone with the general consensus. In

1900, Dr. Walter Reed came to the same

mosquito-borne conclusion, and

historically gets most of the credit for

finding the cause of Yellow Fever.

Read more details about the Yellow

Fever epidemic in Tampa, 1887,

at “A SNEAKY, COWARDLY ENEMY”:

TAMPA’S YELLOW FEVER EPIDEMIC OF

1887-88 by Eirlys Barker.

Read about Dr. John P. Wall, the

first to identify the mosquito as

the carrier of Yellow Fever, in Florida's

Past: People and Events That Shaped

the State, Volume 1 By Gene M.

Burnett

|

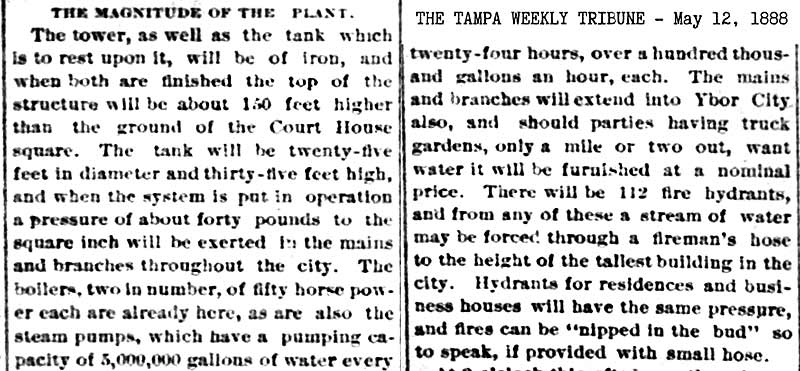

TAMPA'S NEW WATER SUPPLY

When

Jacksonville was hit by yellow fever, northern

capitalists began to shun Florida investments. The

Jeter-Boardman company had trouble getting money and

months passed before it could proceed with Tampa's

water works. Finally, two 1300-foot artesian wells

were drilled at Sixth Street and Jefferson Avenue, a

110,000-gallon stand pipe was constructed, and a

pumping station was completed. 'Water was turned on

April 20, 1889. Now, for the first time, Tampa

people got water merely by turning on a faucet.

|

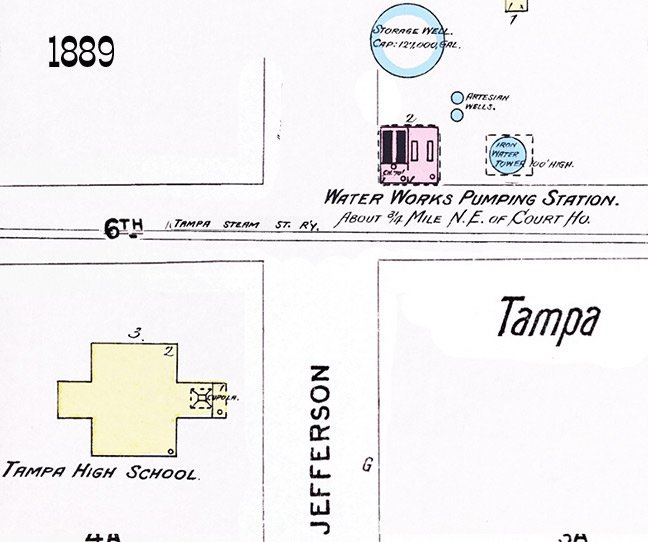

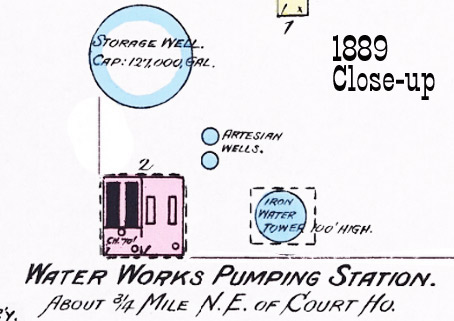

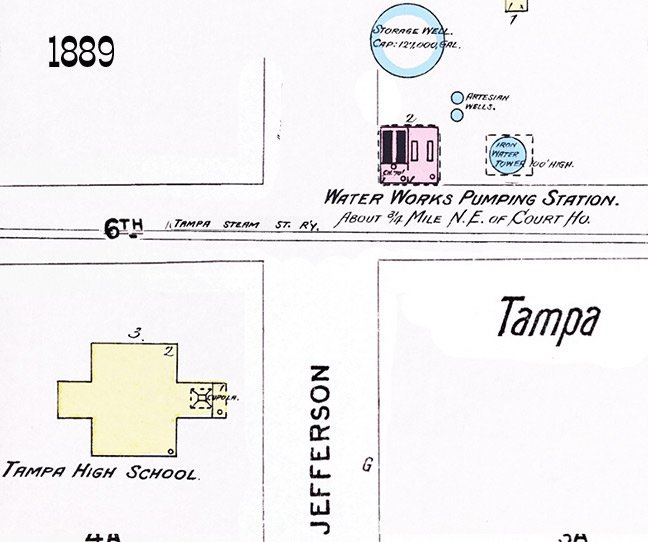

In 1888, the

Jeter-Boardman Waterworks built Tampa's

first pumping station at 6th Ave (a.k.a.

Henderson St.) and Jefferson St,

caddy-corner from the 2nd

home of Hillsborough County High School which

was established there in 1886.

Completion of the water system made

possible an effective fire fighting

organization. Prior to that time Tampa's

firemen had been seriously handicapped

by lack of an adequate water supply. |

|

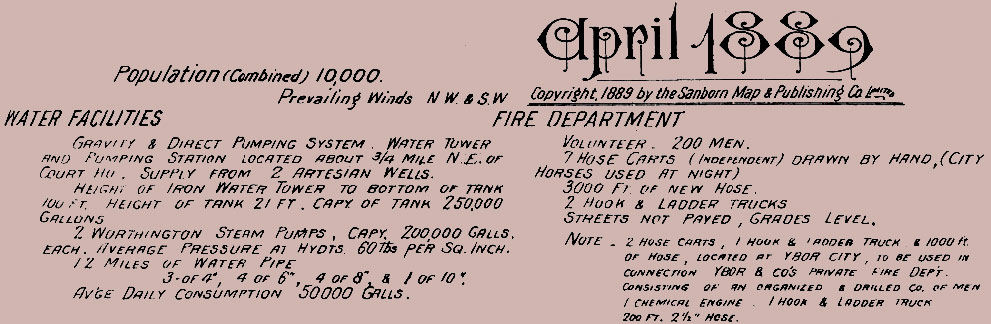

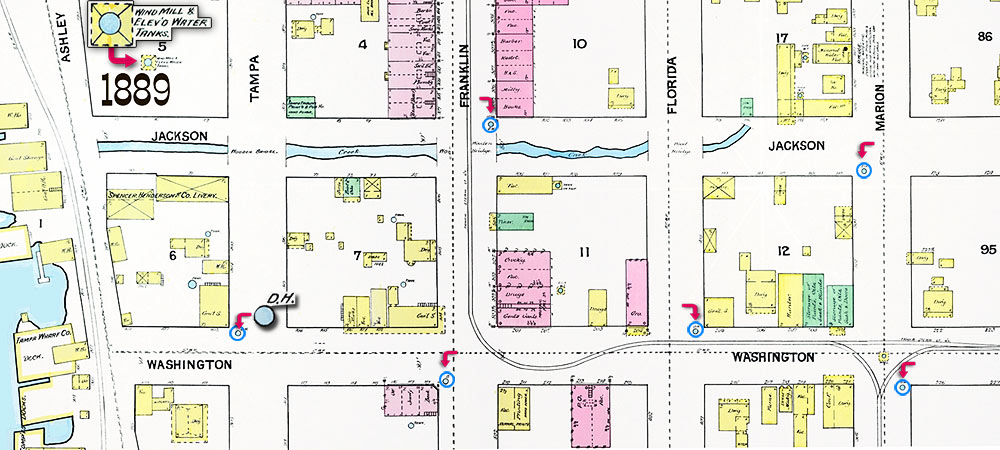

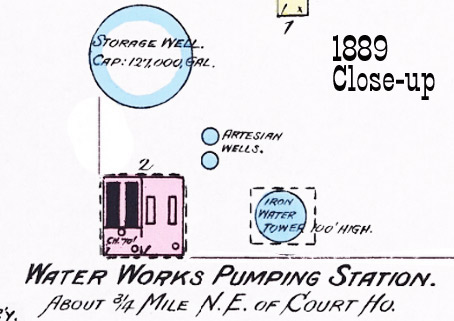

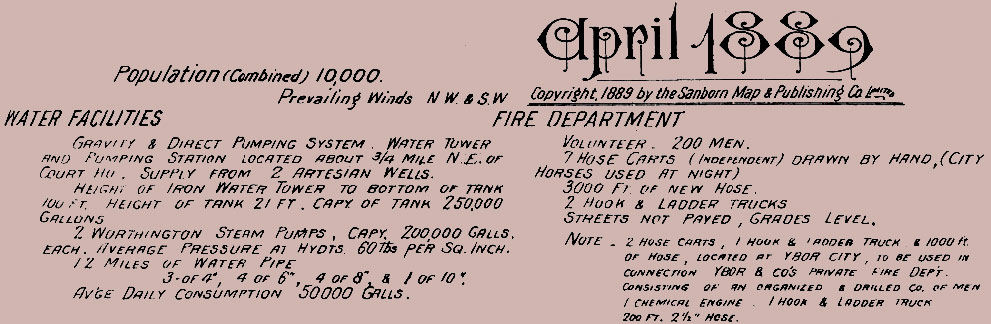

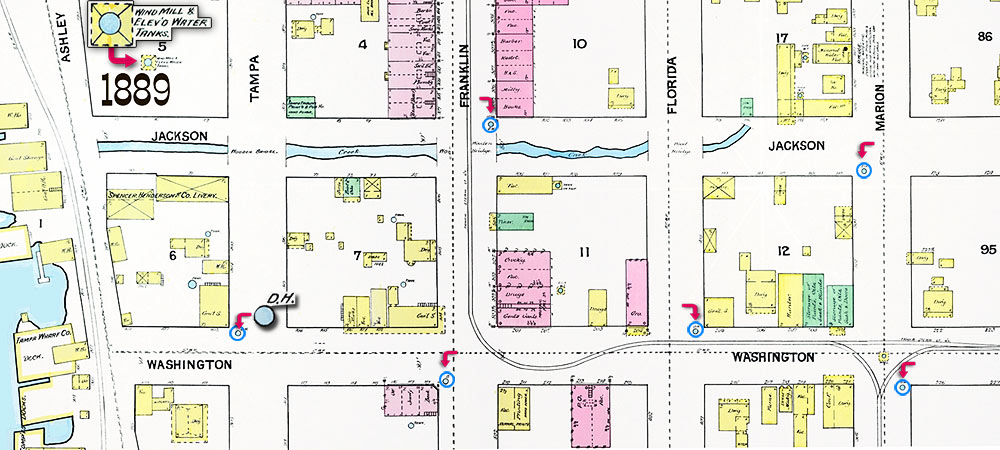

The 1889 maps above (with 1899 streets

added) show Tampa's first pumping

station. It consisted of a deep storage

well and an iron storage tank on a 100

ft. high tower. A detailed description

of the equipment is provided below. The

high school seen in the above left map

was the 2nd

home of Hillsborough (County) High

School.

|

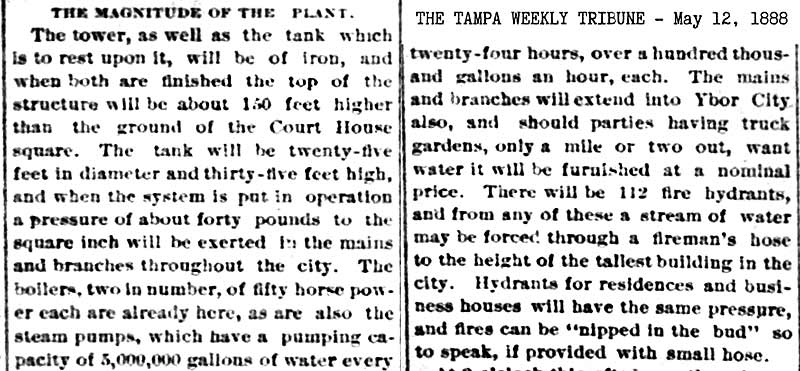

Description of the new water plant supply

See

a more detailed history of Tampa's Waterworks here

at TampaPix.

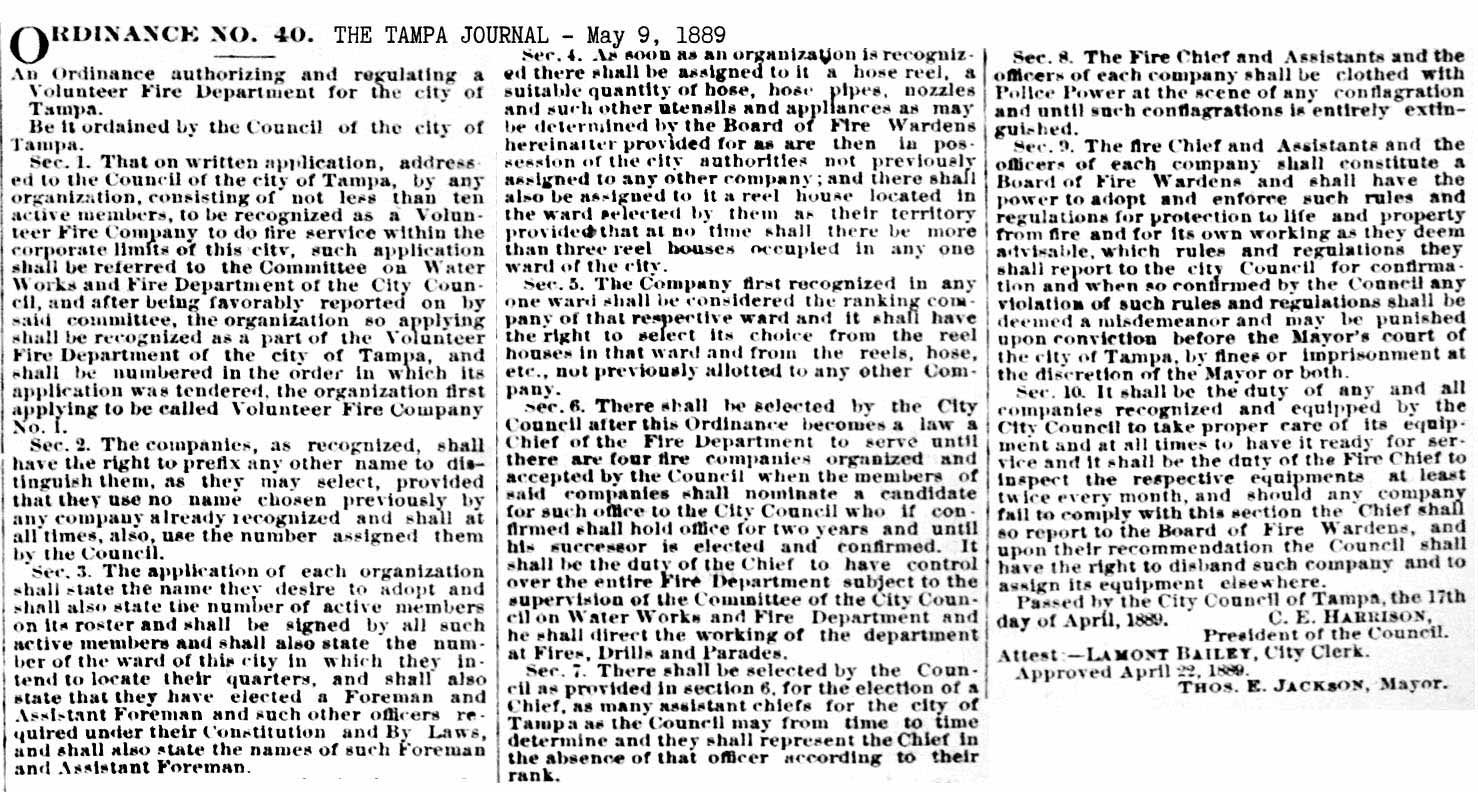

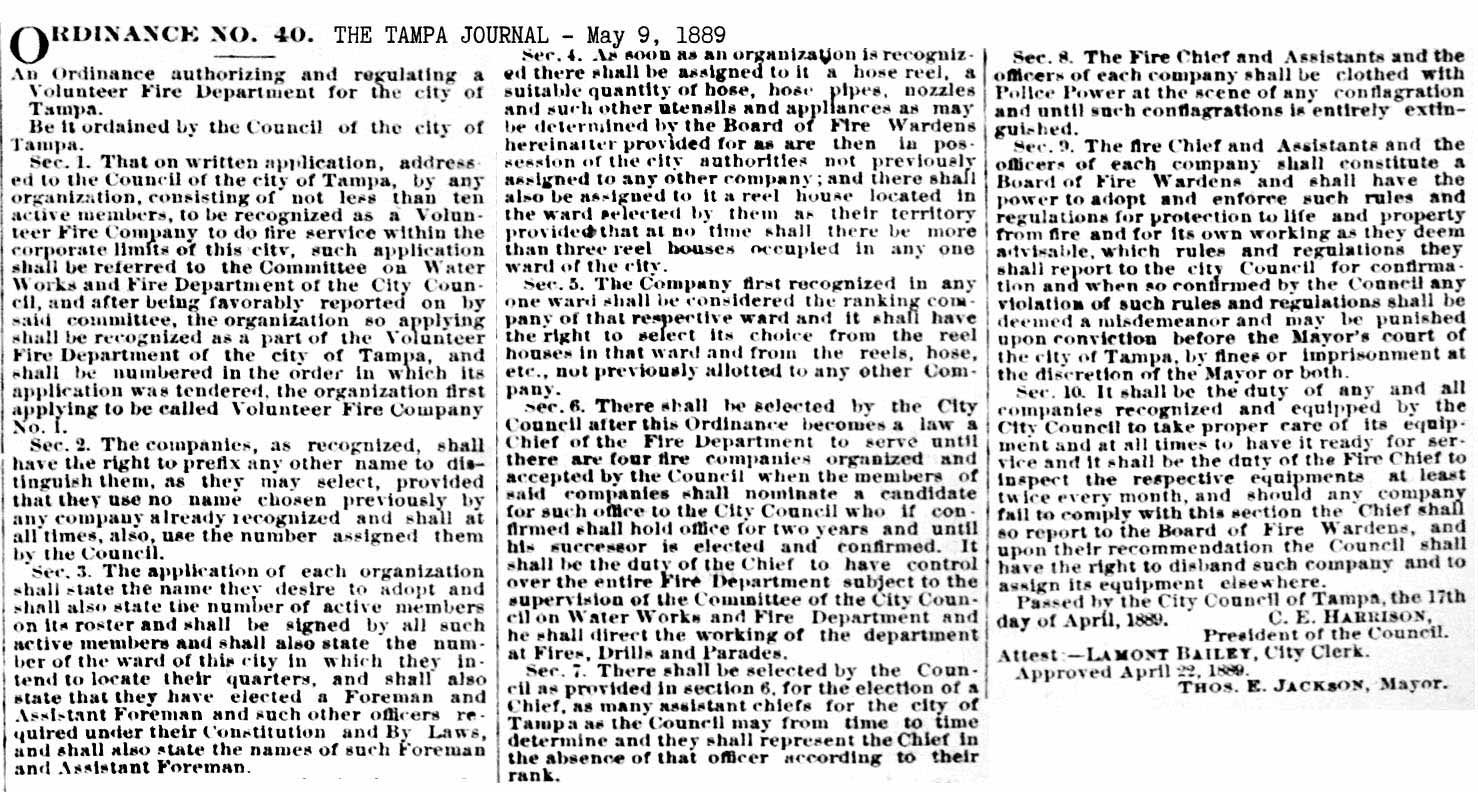

THE

VOLUNTEER FIRE DEPARTMENT IS ESTABLISHED BY CITY

ORDINANCE NO. 40, April 22, 1889

While

plans were being made to build a new city hall/fire

department headquarters at Lafayette St. and Florida

Ave, the city council passed ordinance No. 40 on

April 22, 1889 authorizing the establishment of a

volunteer fire department.

Section 6 as to the election of a Chief: The

City Council would select the Chief until four fire

companies have been organized and accepted by the

Council, at which point the fire companies would

nominate a candidate for the Council to confirm and

serve for two years. ("nominate a candidate" in

those days meant to actually select the

office-holder.)

Section 7 provided for the selection of as many

Assistant Chiefs deemed necessary by the Council.

Click the article to see it larger.

|

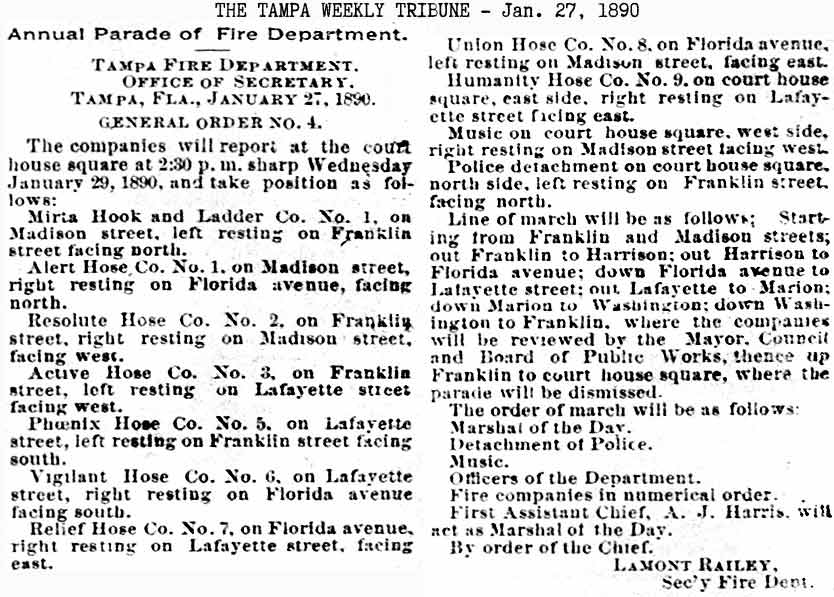

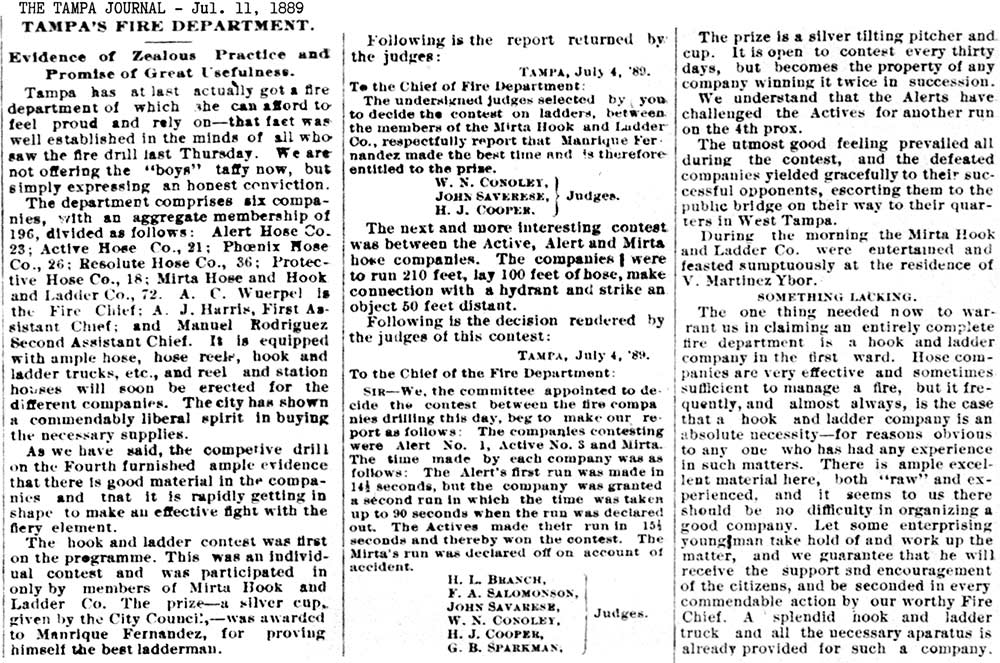

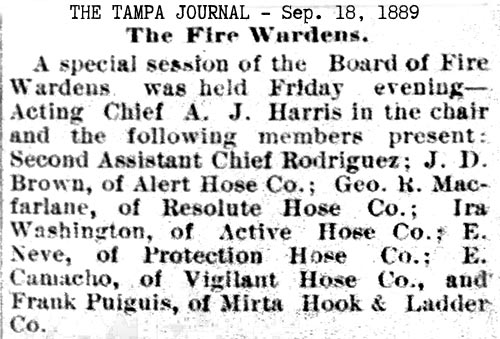

As

permitted under Section 2, fire

companies were formed with names as Alert

Hose Co.No.1, Resolute Hose Co. No.2, Active

Hose Co. No. 3, Protection Hose

Co. No. 4, Phoenix Hose Co.

No.5, and Mirta Hook and Ladder Co. No.

1, which was named for the youngest

daughter of Vicente Martinez-Ybor. |

|

D.B. McKay in his Pioneer Florida

column of Aug 23, 1959, claims seven companies

were formed in the volunteer dept.--Alert, Resolute,

Phoenix, and Mirta, which are named

in the May 29, 1889 fire chief election

article below, but McKay & Grismer add

three not mentioned: Vigilant, Relief,

and Humanity, and does not

mention Active and Protection hose

companies. The discrepancy can be

attributed to not specifying when these

companies were started. TAMPA'S

BRAVEST website uses

McKay's/Grismer's list as well. McKay

also attributes the "Mirta"

name (erroneously) to Ybor's wife instead of his

youngest daughter.

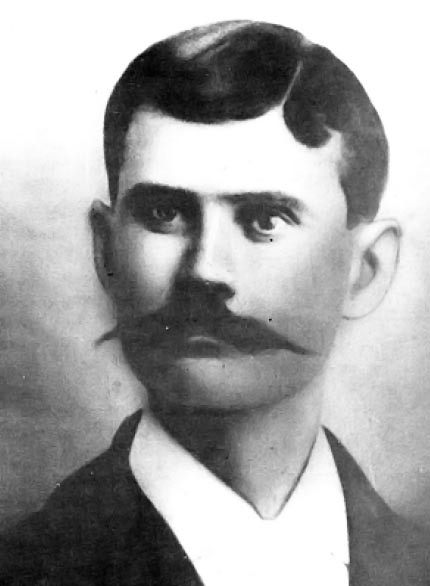

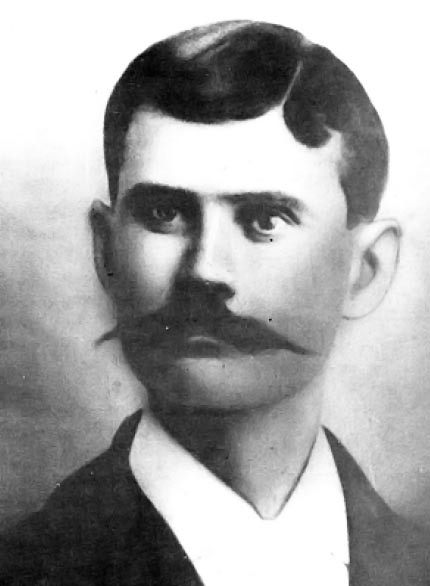

At right: Francisco Puglisi, the first

fire captain in Ybor City history. The

honor was given to him when the Cubans

of the first volunteer fire unit

selected him to head the Mirta Hook &

Ladder volunteer company in 1888. The

unit honored Mr. Ybor's youngest

daughter. In 1886, the four small steam

engines that ran on narrow-gauge rails

between Tampa and Ybor City which pulled

the streetcars were named for Ybor's

daughters Jennie, Mirta and Eloise,

along with Mrs. Ignacio Haya--"Fannie."

|

Photo courtesy of The Sunland Tribune,

Journal of the Tampa Historical Society,

Vol. 3, No. 1 - Nov. 1977, Hampton Dunn,

editor, "The

Italian Heritage in Tampa" by Tony

Pizzo. |

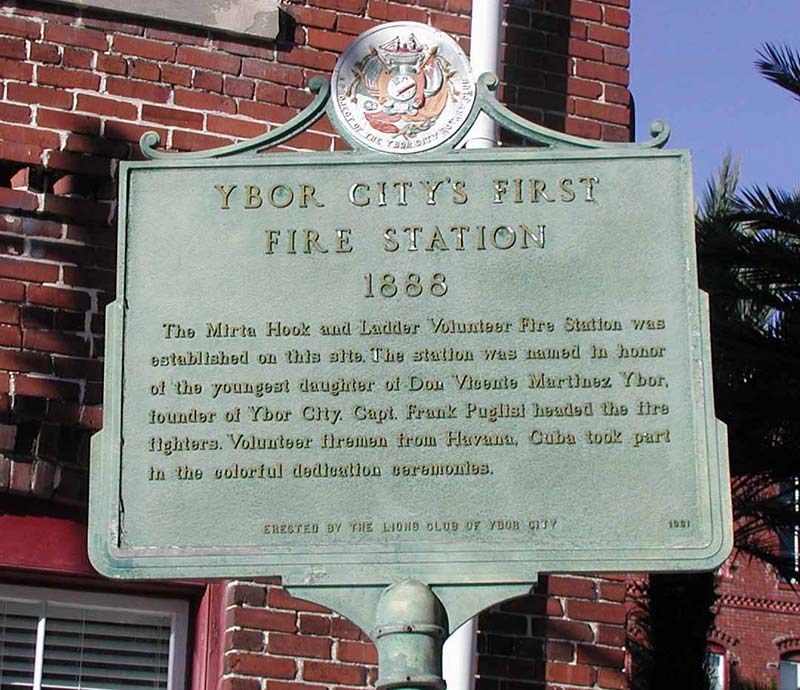

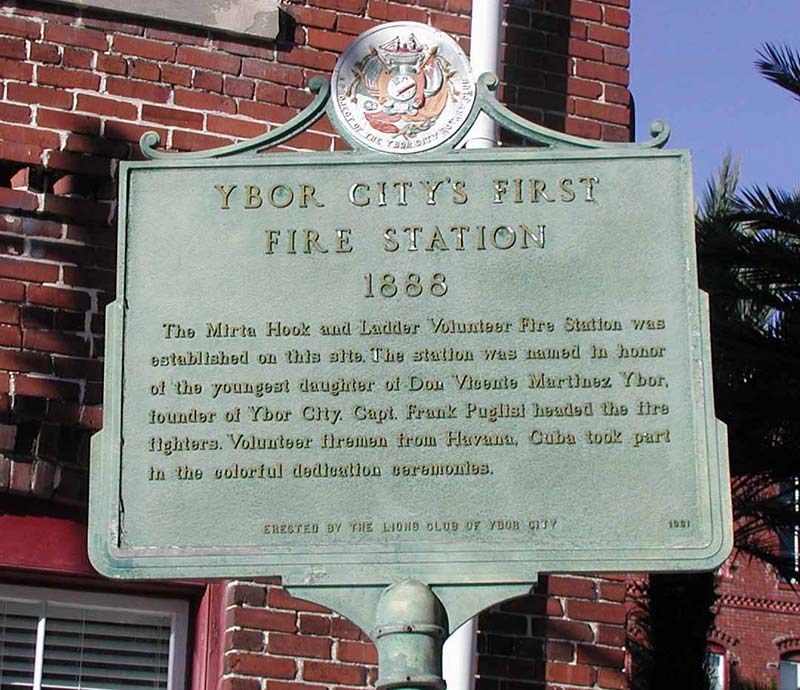

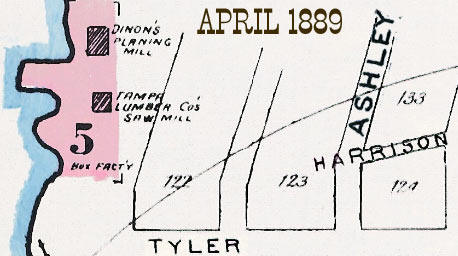

It would appear

that the historic marker is a bit premature in

its claim.

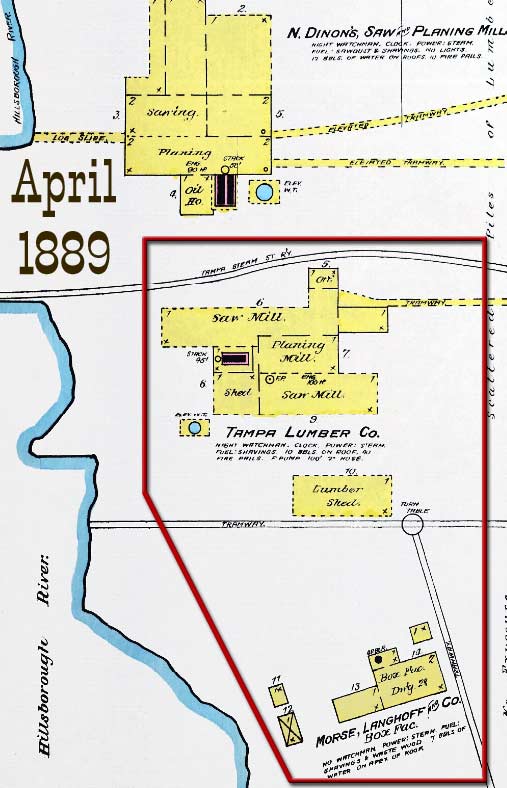

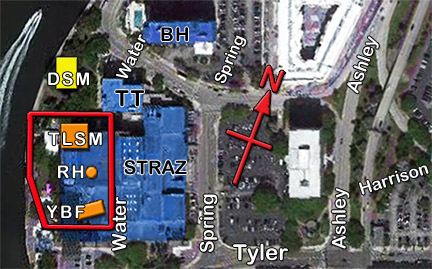

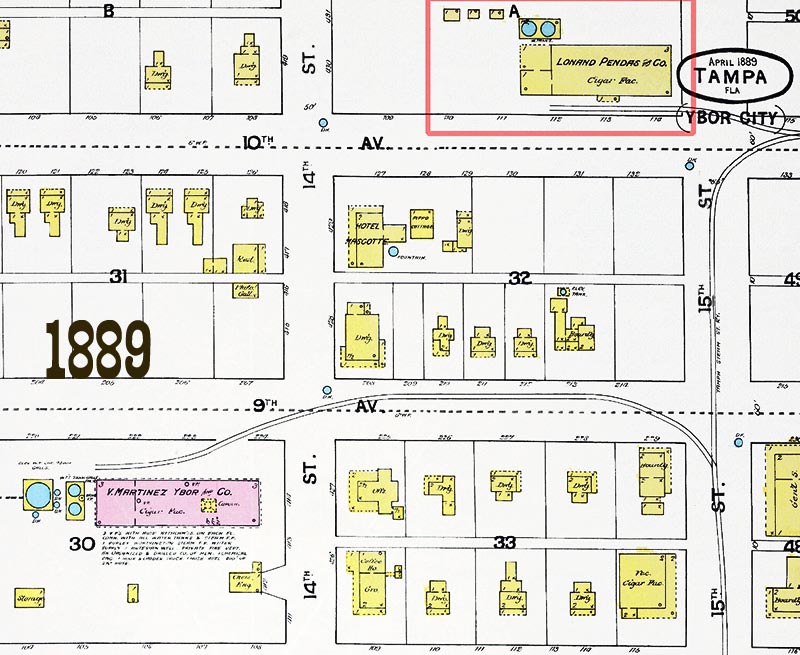

Below is a satellite view of the location of the

historic marker. At this time, the Mirta

company was V. Martinez-Ybor's private fire

fighting company which protected this area

including his factory.

Place your cursor on the map to see this area

from the April 1889 Sanborn fire insurance map.

There apparently was no fire station here in

April 1889 or before then, where the volunteer

firemen worked their shifts. There was a

small wooden structure that housed the chemical

engine which can be seen on the right.

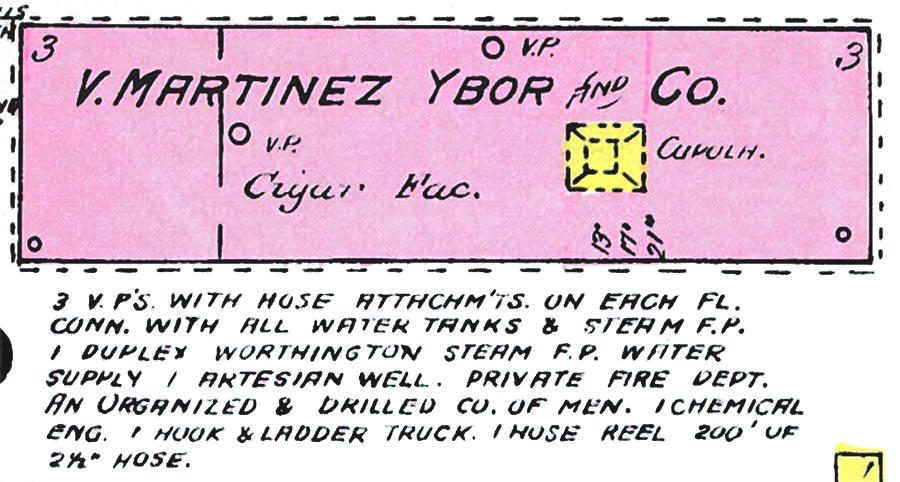

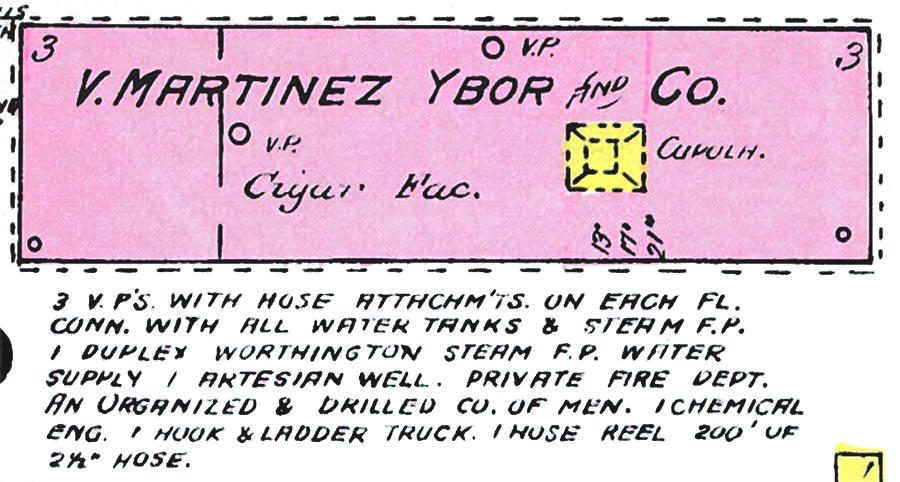

A close up of the

April 1889 map reveals the size and equipment

for the Mirta Company at this time.

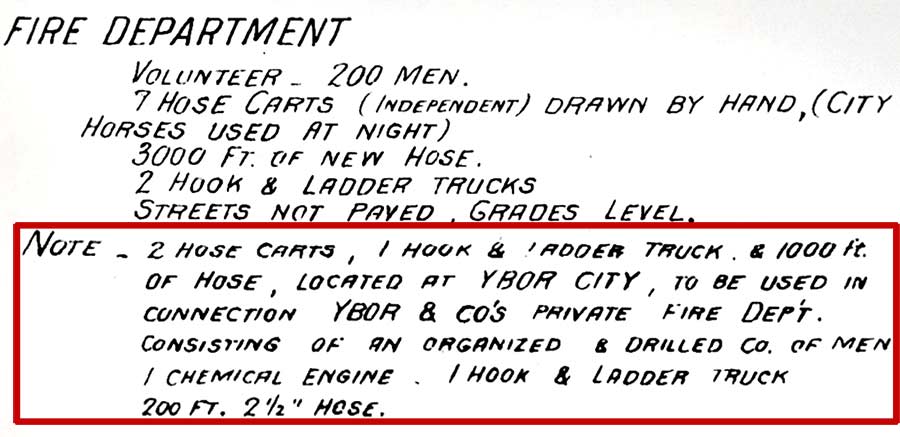

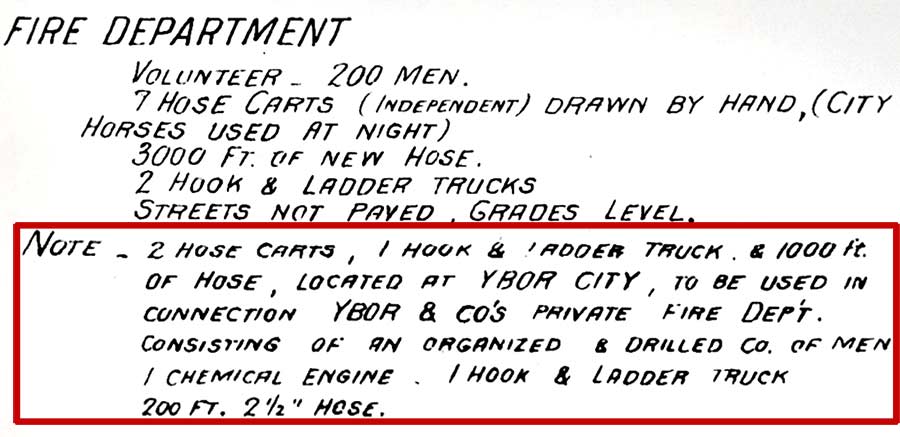

The index on page

1 of the map also provides a description of the

Tampa volunteer fire department, then the

department's equipment in Ybor City (2 hose

carts, 1 hook & ladder truck, 1,000 ft. of

hose)to be used with Ybor's private fire company

("An organized & drilled private co. of men, 1

chemical engine, 1 hook & ladder truck, 200 ft.

of 2.5-inch hose.)

The Mirta Company

fire station was completed and dedicated on Aug.

11, 1890, two months after Chief Wuerpel had

resigned and A. J. Harris had become the Acting

Chief of the volunteer dept.

See the feature about A. J. Harris for the article

about the dedication

of the Mirta fire

house.

The historic

marker should read:

YBOR CITY'S FIRST FIRE STATION, 1890

"The Mirta hook & ladder fire DEPARTMENT was

established on this site as V.M. Ybor's private

fire fighting company. On Aug. 11, 1890,

their first fire station was dedicated for the

use of the Mirta Hook & Ladder Co. and the

Vigilant Hose Co.

In

1889 there were six wells in the heart of the

business district.

1889 Sanborn fire insurance map from the UF

digital maps collection

|

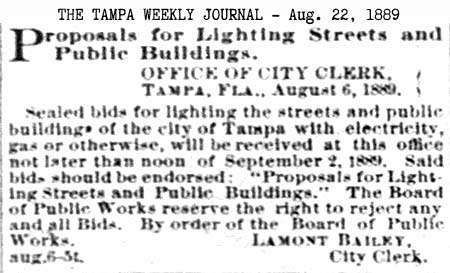

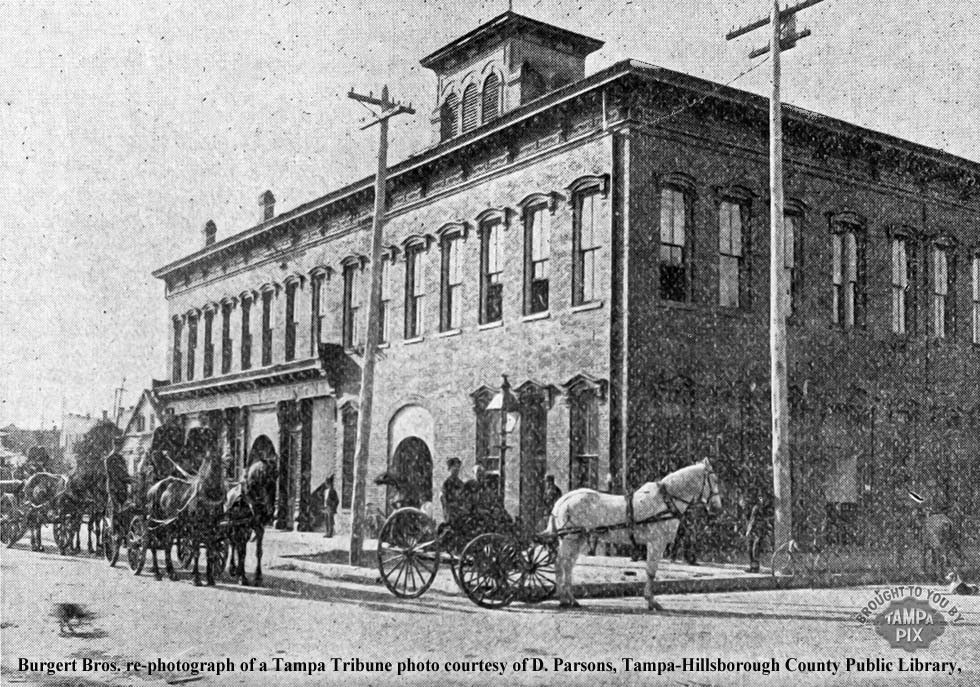

TAMPA PLANS ITS FIRST CITY

HALL

On April

23, 1889 a bond election was held for

the issuance of $100,000 of 7% bonds for

internal improvements which included the

construction of a city hall, fire

station and street paving work. The

result of the election was that 489

votes were cast in favor of the bonds, 7

against, and 6 marked "no bonds." The

election was ratified on April 26 by the

city council and the bonds sold to W. N.

Coler & Co. of New York on May 15, 1889,

and delivered through T. C. Taliaferro

on June 17th.

See more about the planning and

construction of Tampa's first dedicated

City Hall & Fire Headquarters here at

TampaPix.

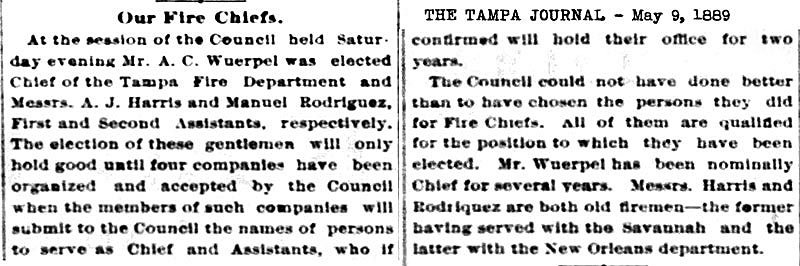

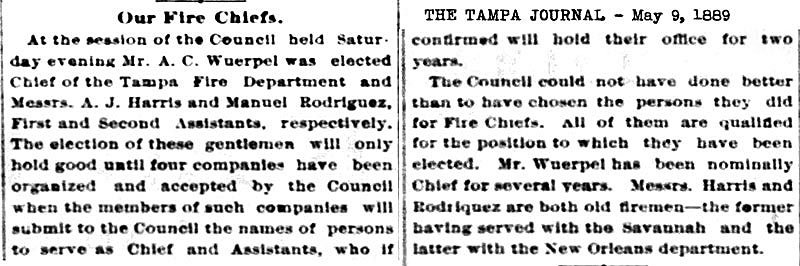

WUERPEL

APPOINTED CHIEF WITH HARRIS 1ST

ASSISTANT AND RODRIGUEZ 2ND ASSISTANT

On May 5,

1889, Augustus "Gus" C. Wuerpel was

chosen by the City Council as Fire Chief

with A. J. Harris and Manuel Rodriguez

serving as first and second assistants,

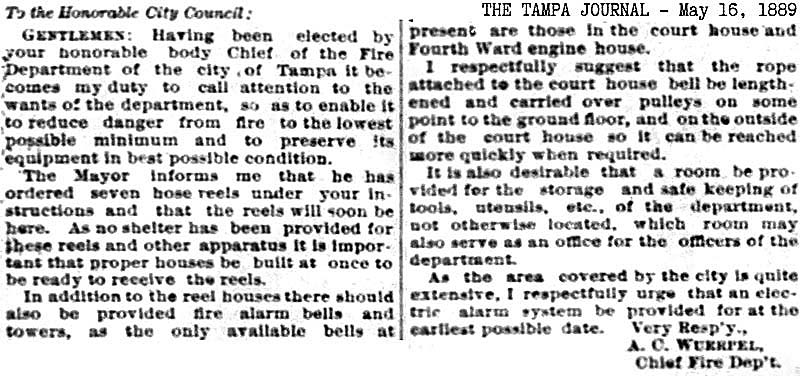

respectively. |

|

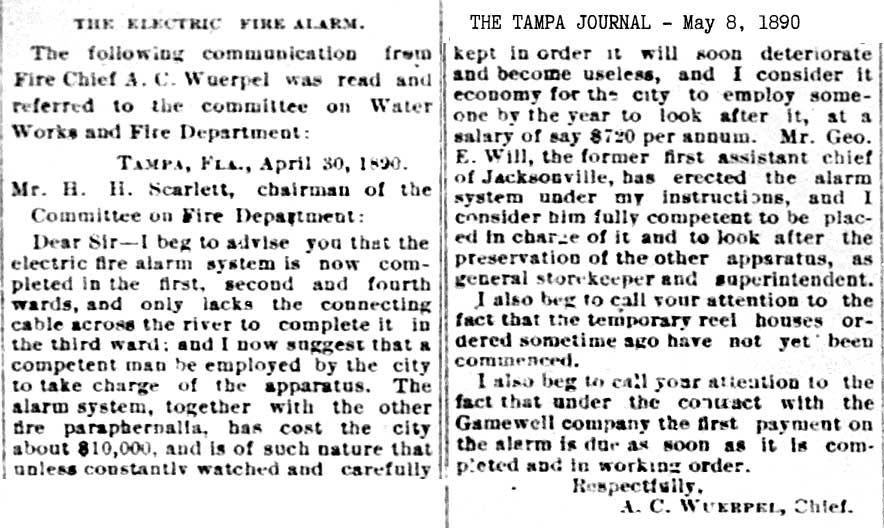

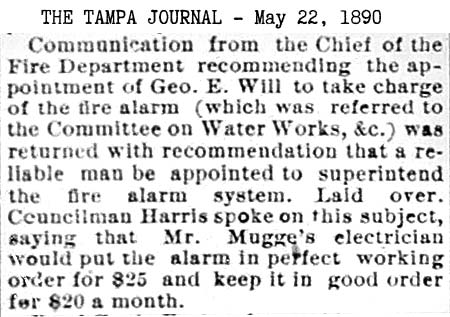

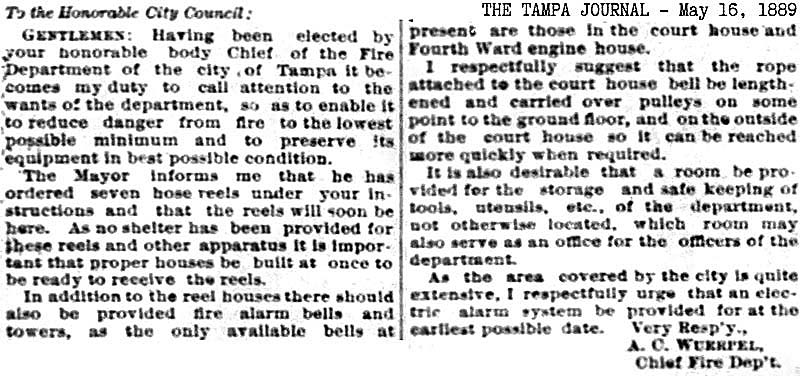

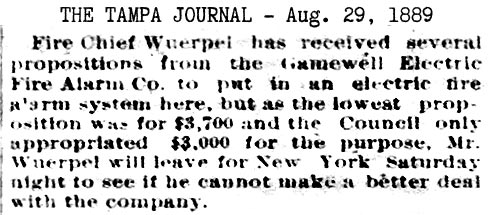

In

addition to the reel houses, Wuerpel

asked for provision of fire alarm bells

and towers, as the only ones at the time

were in the courthouse and the Fourth

Ward engine house. He suggested that

the rope attached to the courthouse bell

be lengthened and carried over pulleys

so they would extend to the ground

floor, and on the outside of the

building so they could be reached more

quickly. Also needed was a "desirable

room" be provided for the storage and

safe keeping of tools, utensils, etc.

not already located in one, with a room

to serve as an office for the officers

of the department. Because of the large

area the city covered, he urged the

council to provide an electric alarm

system as soon as possible.

|

At

this point, in Karl Grismer's History

of Tampa, Grismer makes an erroneous statement,

as does D.B. McKay in Pioneer Florida: At

this point, in Karl Grismer's History

of Tampa, Grismer makes an erroneous statement,

as does D.B. McKay in Pioneer Florida:

On May

18, 1889, A. J. Harris was appointed

chief and competitive fire drills were

held regularly. An electrical fire alarm

system was installed December 9..."

In the

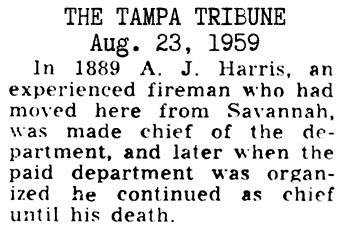

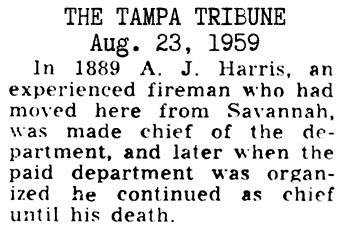

Aug. 23, 1959 Tampa Tribune, D. B. McKay

recounts his memories of the volunteer

fire department in a Pioneer Florida

column "Chief Soaked in Jackson Street

Ditch Water." About halfway through the

column, McKay made the same erroneous

statement as you see at right. No

surprise since D.B. McKay was Grismer's

editor. McKay's memories at that point

were 70 years old.

|

|

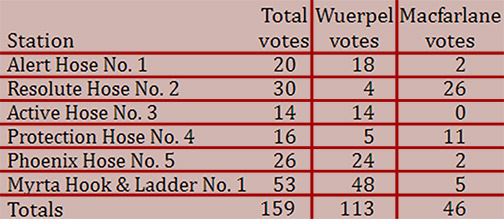

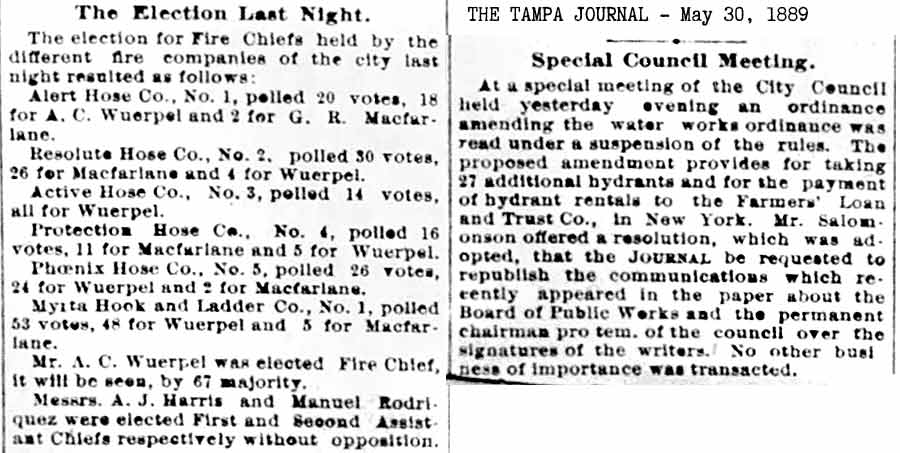

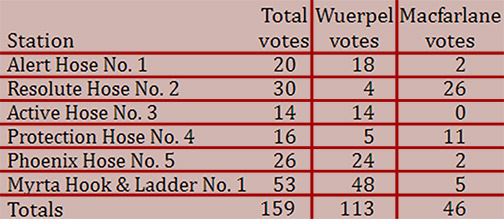

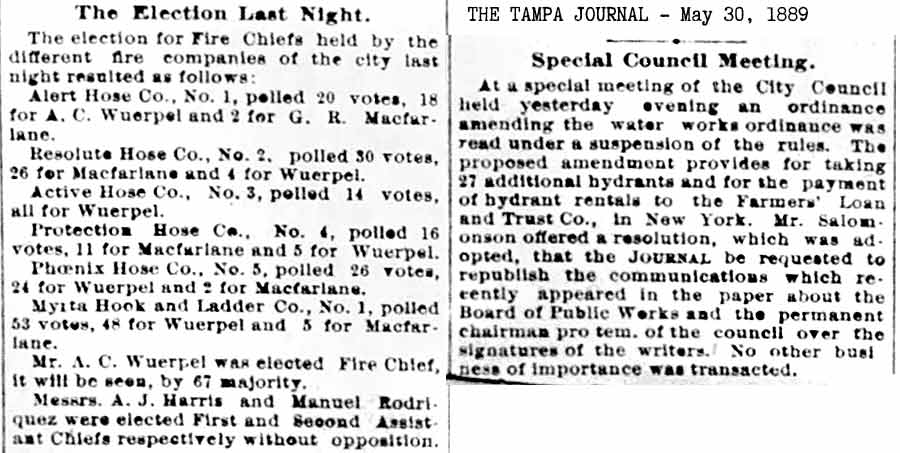

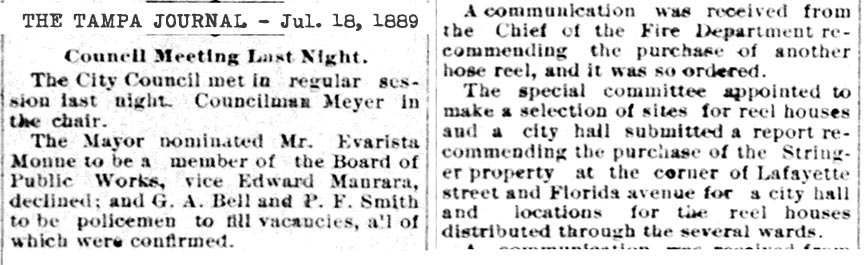

ELECTIONS

On May

29, 1889, as set forth in Ordinance No.

40, elections were held by the six fire

companies around the city to select

their chief. Wuerpel was chosen over

G. R. Macfarlane by a margin of 67

votes. A. J. Harris and Manuel

Rodriguez were elected as first and

second assistants, respectively,

with no opposition.

Also

on May 29, 1889, the City Council

amended the water works ordinance to

provide 27 additional hydrants.

Councilman Fred Salomonson (who

would later serve 3 non-consecutive

terms as Mayor beginning in March,

1893) offered a resolution that the

Tampa Journal republish the article

which was recently in the paper

about the Board of Public Works and

the permanent chairman pro-tem which

was adopted.

|

|

|

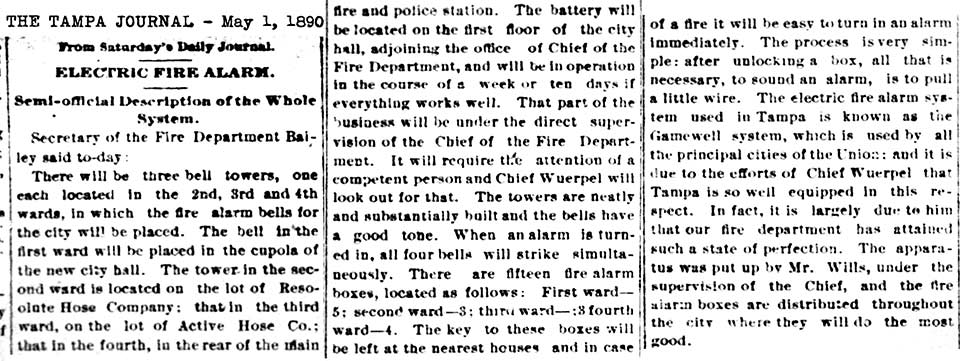

At

Left, the Fire Alarm call box on the corner of Lafayette St.

and Florida Avenue, in front of the 1890 City Hall/Fire

Dept. in 1905.

At

Left, the Fire Alarm call box on the corner of Lafayette St.

and Florida Avenue, in front of the 1890 City Hall/Fire

Dept. in 1905.

The

City of Tampa was established on Jun 2,

1887 when under special act of the state

legislature, the Governor approved a

bill that granted the city of Tampa a

new charter, abolishing the town

governments of Tampa and North Tampa.

Section 5 of the charter provided for a

city-wide election for mayor, eleven

councilmen and other city officials, to

be held on the 2nd Tuesday in July. The

new charter also greatly expanded the

corporate limits of the city. Tampa now

took in North Tampa, Ybor City and some

land on the west side of the

Hillsborough River.

The

City of Tampa was established on Jun 2,

1887 when under special act of the state

legislature, the Governor approved a

bill that granted the city of Tampa a

new charter, abolishing the town

governments of Tampa and North Tampa.

Section 5 of the charter provided for a

city-wide election for mayor, eleven

councilmen and other city officials, to

be held on the 2nd Tuesday in July. The

new charter also greatly expanded the

corporate limits of the city. Tampa now

took in North Tampa, Ybor City and some

land on the west side of the

Hillsborough River.

Leading

citizens considered it an

over-reaction to the

situation when Jacksonville

inflicted a quarantine on

all people from Tampa. This

action was protested by the

editor of the Tampa Weekly

Journal, Harvey Cooper, who

claimed that it hurt the

“Hotel Interest.” Cooper

seemed especially concerned

about Henry Plant’s plans

for building a magnificent

hotel at Tampa to attract

thousands of tourists--and

millions of dollars--every

winter. In defense of

this vision, Cooper

sarcastically reported that

the city was no longer in a

state of panic, and “the

people are laughing at their

own foolishness...Only one

death in Tampa since--the

Lord only knows when, and

that occurred last Sunday.

It was a mule. It would be

dangerous for Jacksonville

to lift their quarantine

against Tampa yet awhile."

Leading

citizens considered it an

over-reaction to the

situation when Jacksonville

inflicted a quarantine on

all people from Tampa. This

action was protested by the

editor of the Tampa Weekly

Journal, Harvey Cooper, who

claimed that it hurt the

“Hotel Interest.” Cooper

seemed especially concerned

about Henry Plant’s plans

for building a magnificent

hotel at Tampa to attract

thousands of tourists--and

millions of dollars--every

winter. In defense of

this vision, Cooper

sarcastically reported that

the city was no longer in a

state of panic, and “the

people are laughing at their

own foolishness...Only one

death in Tampa since--the

Lord only knows when, and

that occurred last Sunday.

It was a mule. It would be

dangerous for Jacksonville

to lift their quarantine

against Tampa yet awhile."

By

September 29, Wall had seen

five suspicious cases,

including two that other

physicians had diagnosed as

bilious remittent fever.

However, he deemed it

“prudent to await further

developments,” for “it is a

very serious thing to

announce the presence of

yellow fever.” Of the

suspicious cases in

September, only Turk’s had

been fatal which suggested

that dengue--a non-fatal

disease with symptoms

similar to yellow

fever--might have been the

cause. Therefore, Wall

continued to observe

possible cases, and he did

not make the fateful

declaration until all his

doubts had disappeared.

By

September 29, Wall had seen

five suspicious cases,

including two that other

physicians had diagnosed as

bilious remittent fever.

However, he deemed it

“prudent to await further

developments,” for “it is a

very serious thing to

announce the presence of

yellow fever.” Of the

suspicious cases in

September, only Turk’s had

been fatal which suggested

that dengue--a non-fatal

disease with symptoms

similar to yellow

fever--might have been the

cause. Therefore, Wall

continued to observe

possible cases, and he did

not make the fateful

declaration until all his

doubts had disappeared.

At

this point, in Karl Grismer's History

of Tampa, Grismer makes an erroneous statement,

as does D.B. McKay in Pioneer Florida:

At

this point, in Karl Grismer's History

of Tampa, Grismer makes an erroneous statement,

as does D.B. McKay in Pioneer Florida:

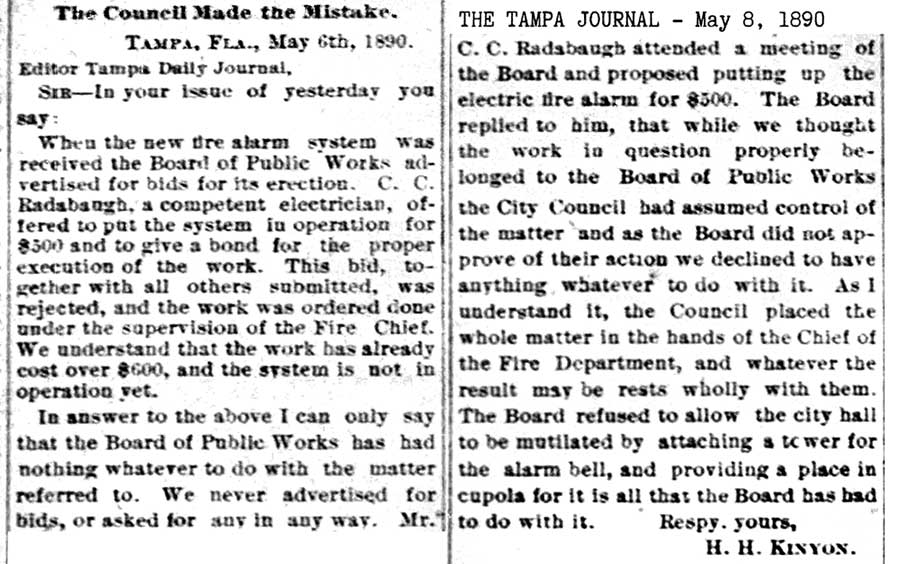

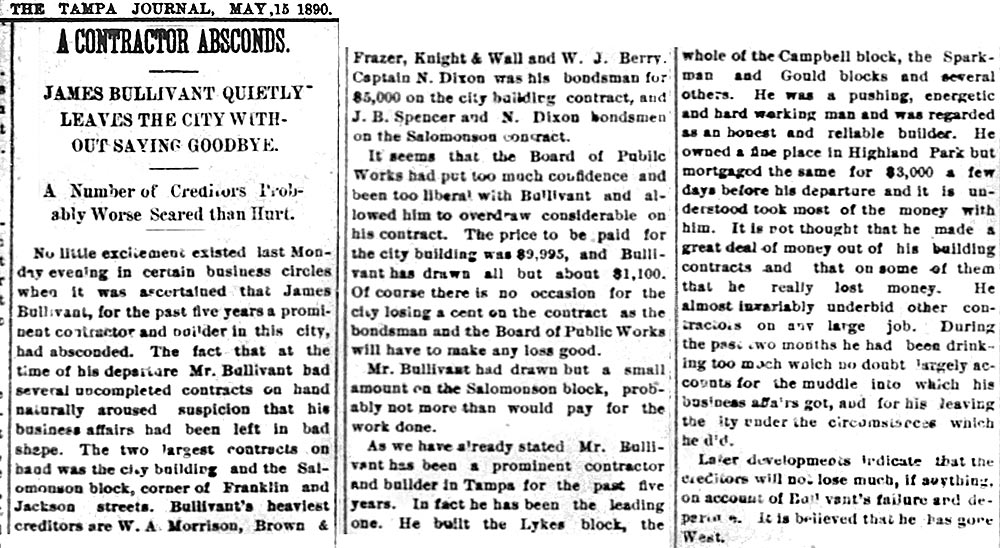

Around

this time, Chief Wuerpel decided to devote more time and

attention to his businesses as its increasing demands

required it, so he tendered his resignation to the council.

Around

this time, Chief Wuerpel decided to devote more time and

attention to his businesses as its increasing demands

required it, so he tendered his resignation to the council.

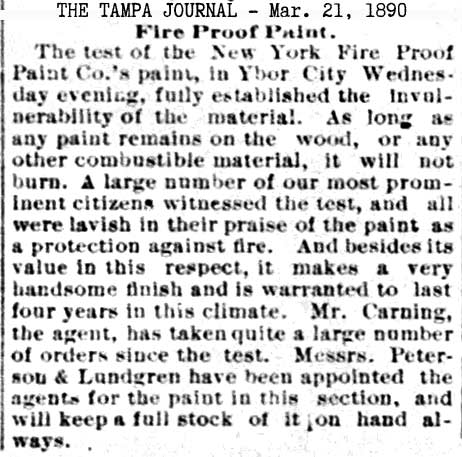

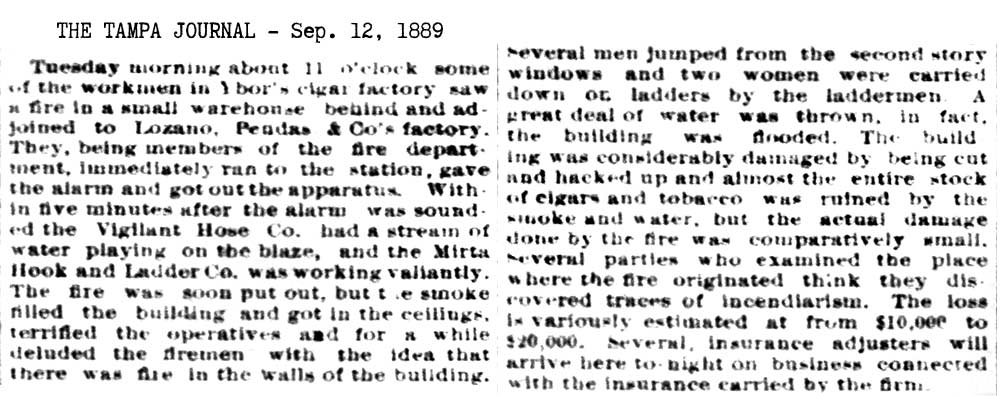

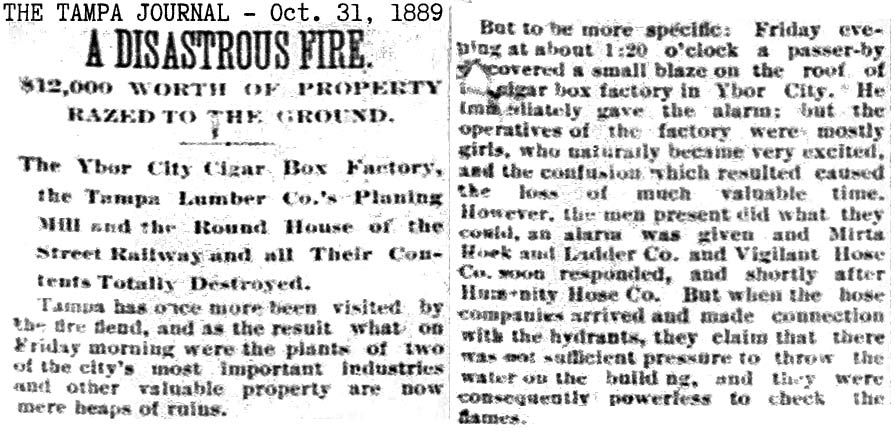

An

alarm was sounded at 1:20 p.m. when a passerby

saw a fire on a small portion of the Ybor City

Box Factory [which interestingly, is not in Ybor

City] so the Mirta Hook & Ladder Co., Vigilant

Hose Co., Humanity Hose Co. and Alert Hose Co.

responded. But upon connecting to the hydrant,

there was insufficient water pressure to spray

water on the fire. When the Alert Hose fire

company arrived from the First Ward, which had

come out in response to a general alarm sounded

from the courthouse bell, they also connected to

a hydrant but no water came from it.

An

alarm was sounded at 1:20 p.m. when a passerby

saw a fire on a small portion of the Ybor City

Box Factory [which interestingly, is not in Ybor

City] so the Mirta Hook & Ladder Co., Vigilant

Hose Co., Humanity Hose Co. and Alert Hose Co.

responded. But upon connecting to the hydrant,

there was insufficient water pressure to spray

water on the fire. When the Alert Hose fire

company arrived from the First Ward, which had

come out in response to a general alarm sounded

from the courthouse bell, they also connected to

a hydrant but no water came from it.