|

Chapter

V: The Clock, "Hortense the Beautiful" - Her Seth

Thomas & McShane Bell Co. Records, Including Costs &

Weights

|

|

Seth Thomas Clock Company was

one of the most prolific and

long lived clock companies. The

quality of their products was

always maintained at an above

average level. Seth Thomas must

have sold many clocks in the

Lafayette, Indiana area, for out

of all the antique clocks we

repair, about 40% are made by

Seth Thomas.

Many American clock factories in

the 19th century suffered

factory fires but Seth Thomas

was fortunate in this respect.

Through conservative growth and

taking advantage of the new

ideas of others, Seth Thomas was

able to enjoy financial

stability, whereas many other

companies faced financial

difficulties.

Seth Thomas was born in Wolcott,

Connecticut in 1785, went to

work for clockmaker Eli Terry in

1807, bought out Terry's factory

(together with Silas Hoadley) in

1810, and in December 1813

bought out Heman Clark's

clock-making business in Plymouth

Hollow.

Thomas continued Clark's wooden

movement tall clock production,

and about 1817 began making the

wooden movement shelf clock.

These were cased in pillar and

scroll cases until 1830, when

the bronze looking glass and

other styles became popular. In

1842, brass movements were

introduced, and first cased in

the popular O.G. case (which was

made until 1913). Wood movements

were phased out in 1845. In 1853

Mr. Thomas incorporated the Seth

Thomas Clock Company, so that

the business would outlive him.

Mr. Thomas died in 1859, and

Plymouth Hollow was renamed

Thomaston in his honor in 1865.

Many Seth Thomas clocks from

1881 to 1918 have a date code

stamped in ink on the case back

or bottom. Usually, the year is

done in reverse, followed by a

letter A—L representing the

month. For example, April 1897

would appear as 7981 D.

In 1930 a holding company named

General Time Instruments

Corporation was formed to unite

Seth Thomas Clock Company with

Western Clock Company.

In 1955, a flood badly damaged

the Seth Thomas factory. They

phased out movement

manufacturing and began

importing many movements from

Germany. Hermle, in the Black

forest of Germany, has made many

movements for Seth Thomas

clocks.

|

History

from

Antique Seth

Thomas Clocks.com

|

In 1968, General Time was bought

by Talley Industries, and in

1979 the headquarters was moved

to Norcross, GA.

In June 2001 General Time

announced that it was closing

its entire operation. The

Colibri Group acquired Seth

Thomas. The NAWCC (the National

Association of Watch and Clock

collectors) purchased from Seth

Thomas their collection of

historical records, drawings,

photographs, advertisements and

documents.

In January, 2009, The Colibri

Group unexpectedly shut its

doors, laying off its 280

employees and preparing to sell

all remaining jewelry, gold and

silver to pay creditors. I don't

know yet what this means for

Seth Thomas.

The following message appeared

on the Colibri website:

February 16, 2009

The Colibri Group is currently

in receivership and is not

accepting any orders at this

time. We are also unable to

repair or replace any items

returned to us for the time

being. We will do our best to

ensure that items that have been

sent to us will be returned to

the respective customer or

owner. We will update this

message as new information

becomes available. We are sorry

for the inconvenience. Thank you

for your patience."

This history continues at

CLOCK HISTORY.COM |

|

|

|

HORTENSE'S

ACTUAL

MEASUREMENTS

&

COSTS FROM THE SETH

THOMAS CLOCK CO.

AND McSHANE BELL

CO.

|

|

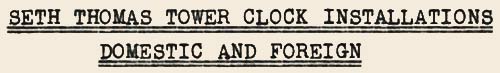

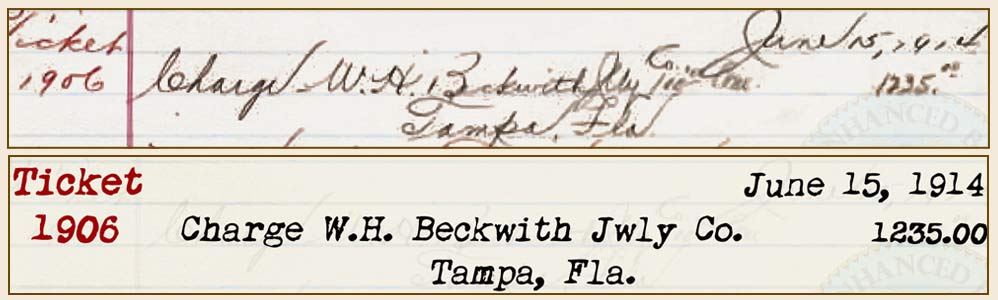

Seth Thomas

Clock Co.

records show

that Hortense

was ordered for

Tampa City Hall

installation in

June 1914 and

assembly

completed in

May, 1915.

She was a Seth

Thomas No. 16, hour-strike

tower clock with

Graham

escapement.

Five other

locations in

Florida had same

model 16; one was

made for E. Neve

& Co. in Jan.

1882.

For

tower clocks, the Seth Thomas

serial number is their

production number.

Hortense was production No.

1906, she is found in book M for

clocks made from 11-Aug-1913 to

22-June-1915.

This explains why some newspaper articles

claim she was made in 1906, it's

on the plate fastened

to the front of the clock.

She was made in 1915, NOT 1906.

Chart at right is courtesy "Seth

Thomas Tower Clocks at

TSC Chapter 134.org |

Clock

Serial Number |

Book |

Dates |

| 1 to 360 |

Book A, |

from 12

July, 1872 to 24 April,

1877 |

| 361 to

502 |

Book B, |

from 28

April, 1877 to 30

January, 1885 |

| 503

to715 |

Book C, |

from 2

February, 1885 to 3

December, 1888 |

| 716 to

851 |

Book D, |

from 14

December, 1888 to 8

July, 1892 |

| 852 to

1013 |

Book E, |

from 9

July, 1892 to 13 May,

1895 |

| 1014 to

1100 |

Book F, |

from 13

May, 1895 to 19 May,

1899 |

| 1101 to

1248 |

Book G, |

from 19

May, 1899 to 28 May,

1901 |

| 1246 to

1408 |

Book H, |

from 28

May, 1901 to 20

February, 1904 |

| 1246 to

1407 |

Book I, |

from 26

February, 1904 to 4

January, 1906 |

| 1408 to

1594 |

Book J, |

from 3

January, 1906 to 17

December, 1909 |

| 1595 to

1738 |

Book K, |

from 11

January, 1910 to 21

December, 1911 |

| 1739 to

1840 |

Book L, |

from 3

January, 1912 to 19

August, 1913 |

|

1841 to 1951 |

Book M, |

from 11 August, 1913 to

22 June, 1915 |

| 1952 to

2051 |

Book N, |

from 26

June, 1915 to 20

October, 1917 |

| 2052 to

2145 |

Book O, |

from 7

December, 1917 to 18

March, 1920 |

| 2146 to

2266 |

Book P, |

from 13

April, 1920 to 9 August,

1922 |

| 2267 to

2400 |

Book Q, |

from 9

August, 1922 to 2 April,

1924 |

| 2401 to

2528 |

Book R, |

from 17

May, 1924 to 3 December,

1925 |

| 2529 to

2657 |

Book S, |

from 11

December, 1925 to 28

December, 1927 |

| 2658 to

2796 |

Book T, |

from 12

January, 1928 to 4

November, 1929 |

| 2797 to

2950 |

Book U, |

from 4

November, 1929 to 14

April, 1932 |

| 2951 to

? |

Book V, |

from 14

April, 1932 to 23 June,

1936 (Extrapolated) |

| ? + 1 to

?? |

Book W, |

from 23

June, 1936 to ----

(Extrapolated) |

|

|

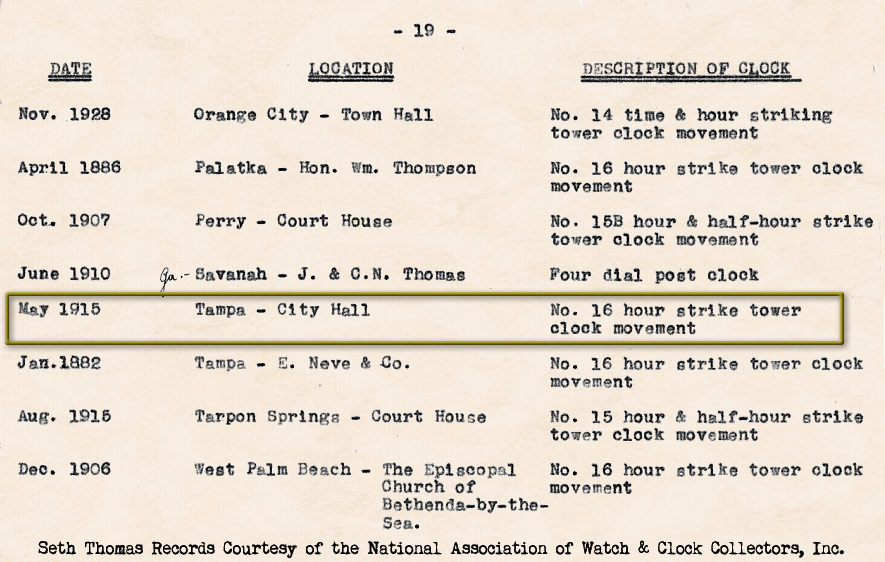

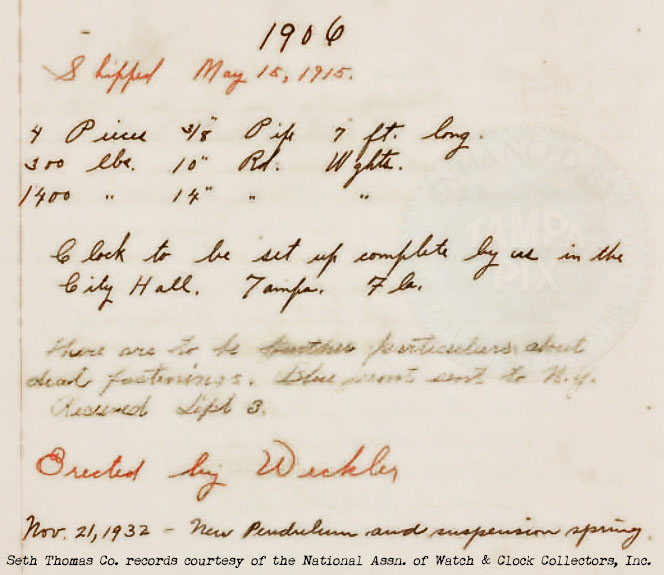

HORTENSE'S PRODUCTION

RECORDS

|

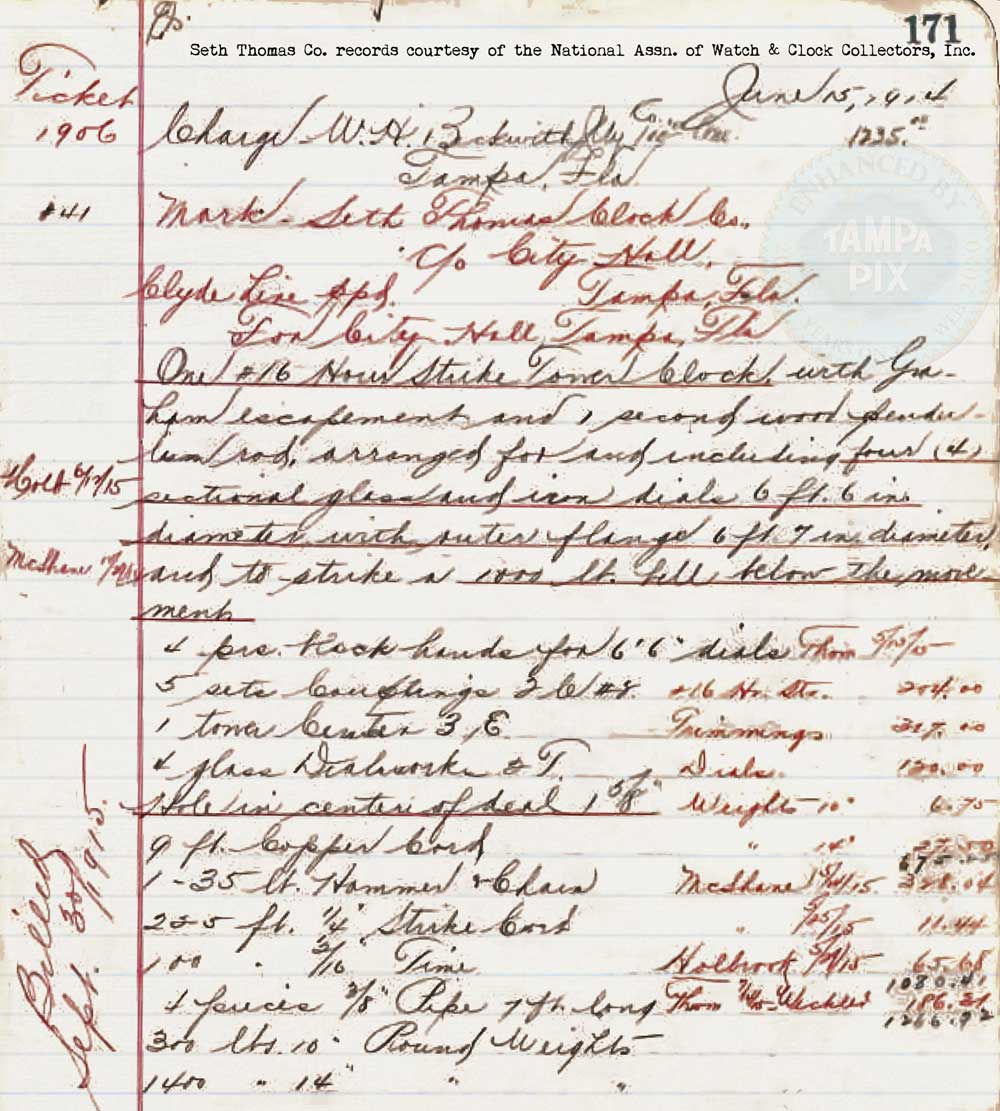

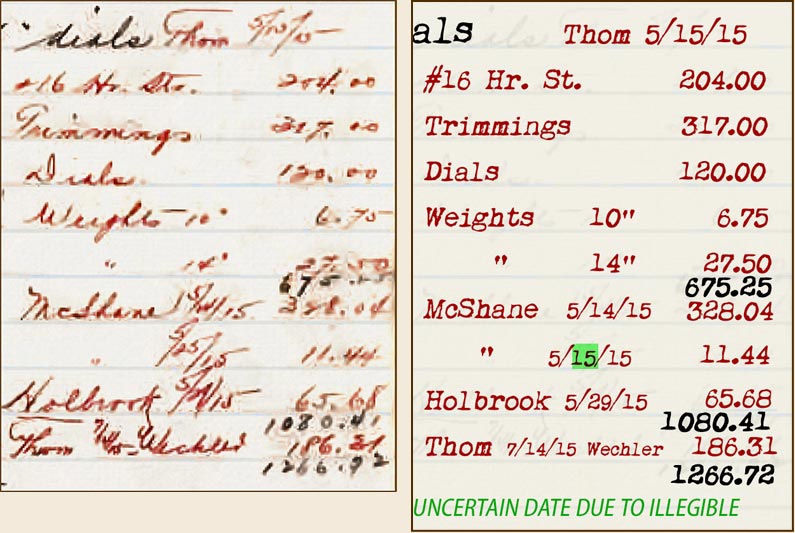

First page

Mouse-over the

image to see it

transcribed.

Second page

Mouse-over the

image to see it

transcribed.

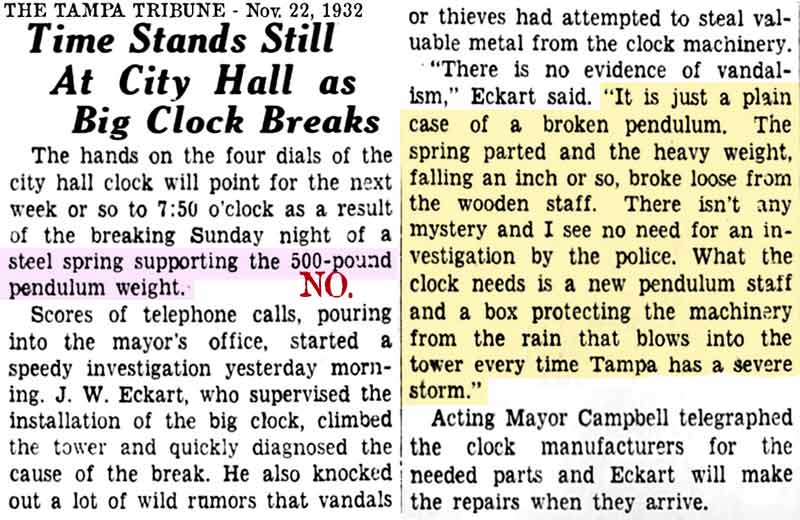

Notice above

Nov. 21, 1932

order of new

pendulum and

spring to

replace the

broken one

described in the

article below.

The pendulum did

NOT weigh 500

lbs.

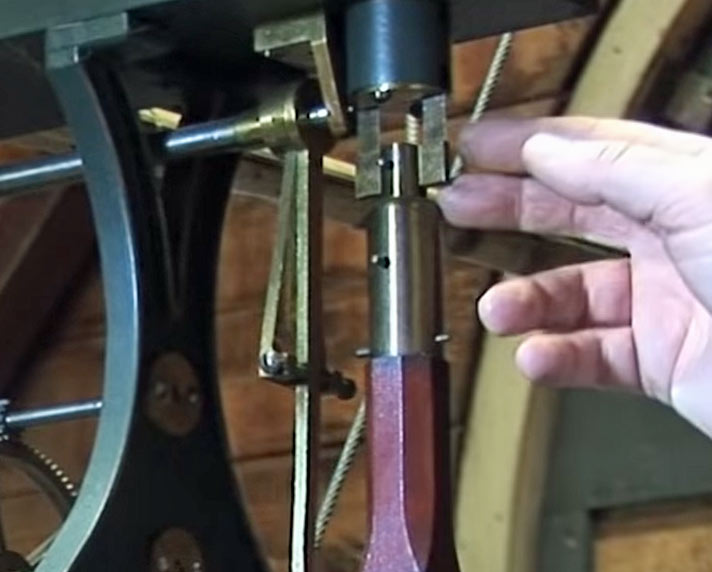

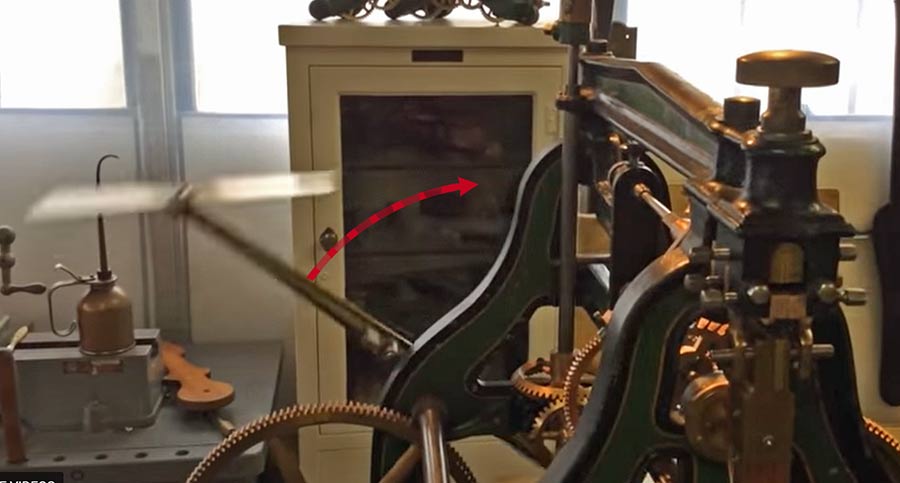

THE PENDULUM AND

SPRING

This screen shot

from a Trevor

Murphy video

featured below

shows him

pointing to the

spring that

suspends the

pendulum.

It appears to be

two metal plates

that are thin

enough to flex

from side to

side as the

pendulum swings.

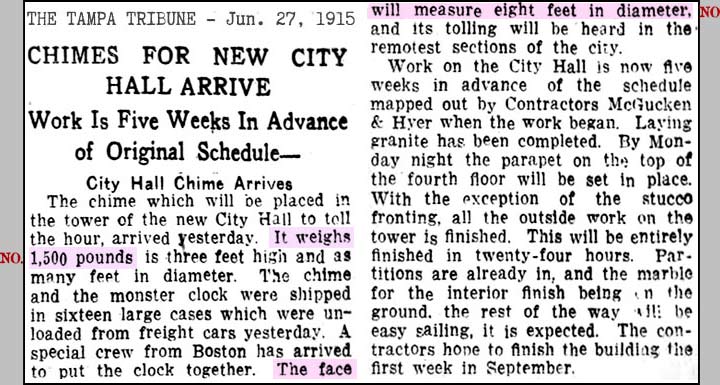

According to

this article,

the "monster

clock"

arrived in

SIXTEEN large

cases.

This is A LOT of

luggage, for a

clock, however,

figure it has

four faces and

each face is

made up of 6

"pie wedges"

glass backing

with its

corresponding

portion of the

dial. (The

bell has

increased 500

lbs. since the

previous

description and

the dials

increased

another

half-foot from

the previous

one.)

Trevor Murphy

has some

excellent

YouTube videos

which are very

well shot and

narrated.

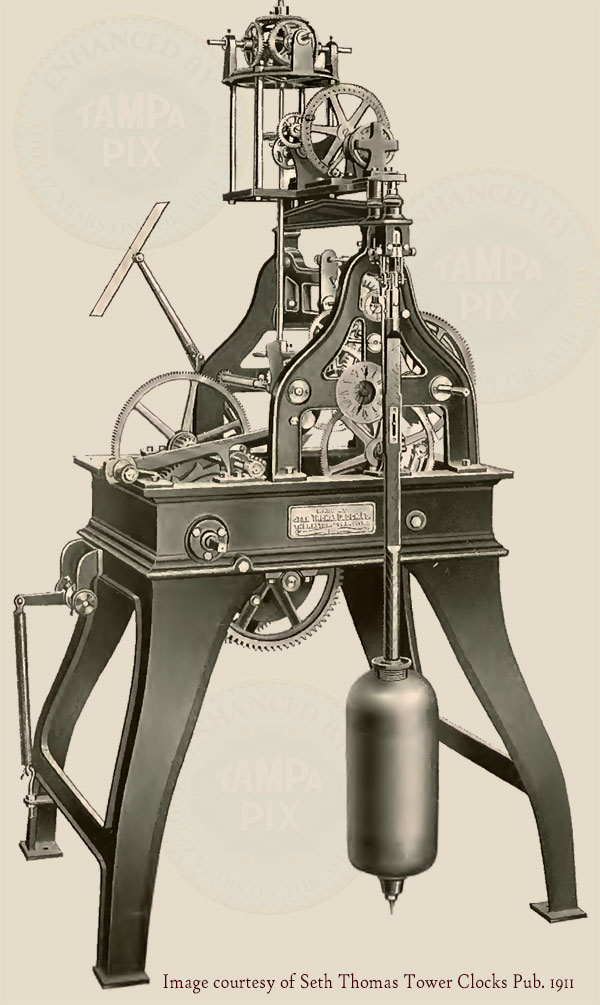

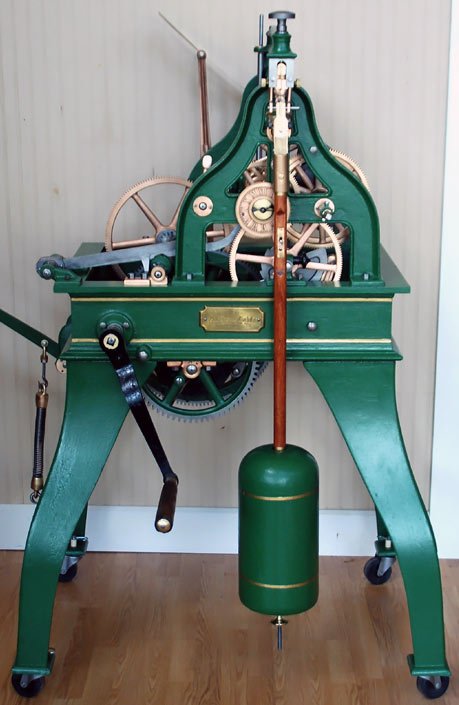

HOOD

COUNTY

COURTHOUSE

TOWER

CLOCK,

TEXAS

The

Seth

Thomas

#16

Tower

Clock

seen

at

right

was

a

restoration

job

done

for

the

Hood

Co.

Texas

courthouse.

It

appears

to

be

identical

to

Hortense

except

that

the

gear

assembly

at

the

top

that

connects

to

the

clock

face

drive

shafts

aren't

attached

here.

The

object

sticking

up

in

the

back

can

also

be

seen

in

the

Seth

Thomas

diagram

above.

It

is

one

of

two

fan

blades

held

by

a

wooden

rod here.

The

actual

fan

blade

is

seen

on

edge.

Extending

downward

would

be

another

identical

rod

and

blade

and

together

the

whole

assembly

rotates

like

a

propeller.

The

plates

produce

a

wind

resistance

just

like

a

fan.

This

controls

the

speed

at

which

the

hammer

strikes

the

bell.

In

other

words,

it

acts

as a

"governor"

for

the

strike

mechanism

due

to

its

air

resistance.

Without

this,

the

weights

would

freefall

and

spin

the

drum

faster

and

faster,

while

the

hammer

would

beat

away

at

the

bell

like

a

jackhammer.

Until

the

weights

bottomed

out,

snapping

the

strike

cord,

and

continuing

to

plummet

through

a

floor

or

two

of

City

Hall.

(Not

to

mention

probably

sending

the

drive

chain

flying

through

a

wall.)

One

of

the

videos

below

show

this

mechanism

in

action. |

Seth

Thomas

Clocks

info

below

is

courtesy

of

Seth

Thomas

Tower

Clocks

(1911)

from SurvivorLibrary.com

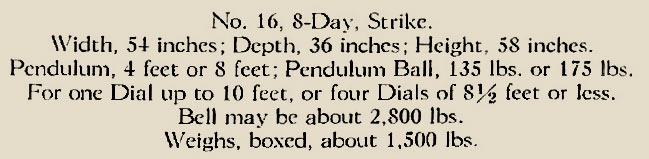

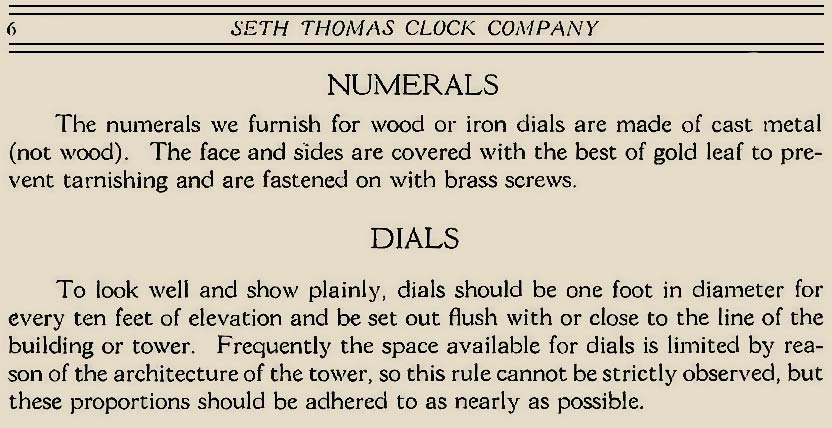

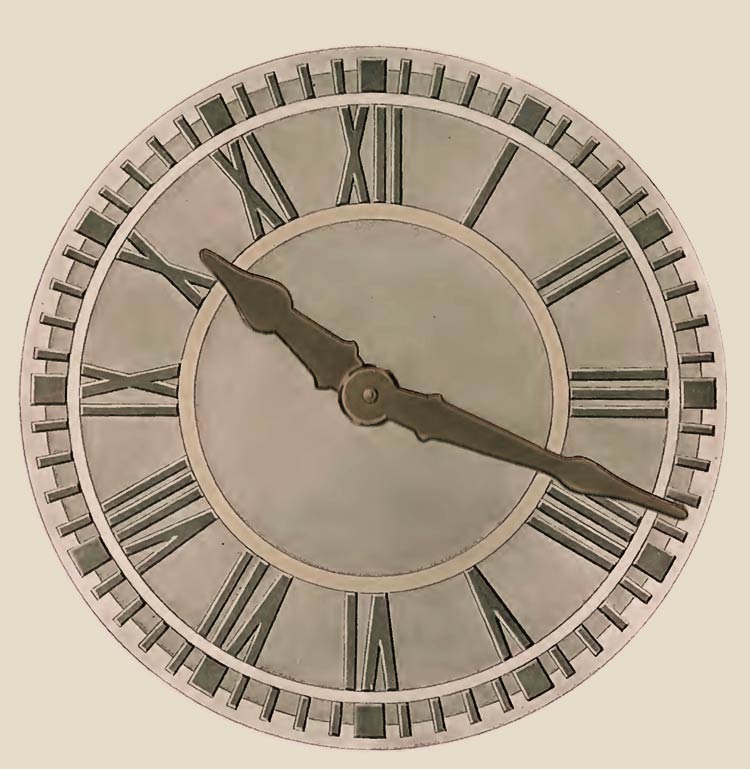

Hortense

is a

#16

Seth

Thomas

Hour

Strike

tower

clock.

She

had

a

Graham

escapement

and

had

a 1

second

wood

pendulum.

She

had

four

sectional

glass

and

iron

dials

6 ft

6

in.

in

diameter.

According

to a

few

newspaper

articles

published

during

construction

of

City

Hall,

and

installation

of

the

clock,

the

floor

of

the

room

where

the

clock

mechanism

is

housed

is

133.5

feet

above

ground.

Using

Seth

Thomas'

guide

for

dial

size,

Hortense's

dials

should

have

been

just

over

13

feet

in

diameter

for

optimum

visibility.

|

There

were

two

weights

that

powered

Hortense.

Ten-inch

round

weights

totaling

300

lbs.

ran

the

clock

mechanism,

which

was

suspended

by

100

ft.

of

5/16" dia.

"Time

Cord,"

and

fourteen-inch

round

weights

totaling

1,400

lbs.,

which powered

the

bell

strike

mechanism.

Those

weights

were

suspended

by

225

feet

of

.44" dia.

"Strike

Cord."

Much

more

weight

is

needed

to

lift

and

drop

the

heavy

THIRTY-FIVE

LB. bell

hammer.

As

you

will

see

in

one

of

the

videos

to

follow,

the

"Time

Cord"

is

wrapped

around

a

cylinder

in

ONE

LAYER

only.

This

is

because

a

second

layer

would

have

a

larger

diameter

winding

and

cause

a

different

value

torque

to

be

exerted

on

the

driving

gears.

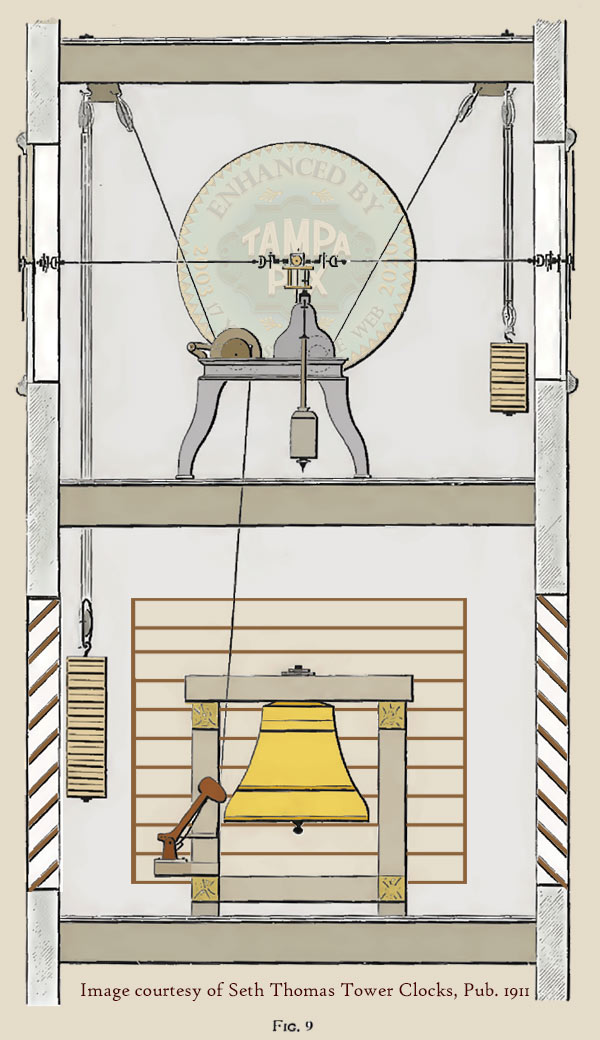

BELOW

IS A

TYPICAL

INSTALL

ARRANGEMENT

FOR

A

#16

CLOCK

The

strike

cord

can

be

seen

on

the

left

and

the

time

cord

on

the

right.

Both

are

fastened

to

the

ceiling

first

and

then

to a

block

&

tackle

pulley

system

which

makes

rewinding

of

the

the

weights

easier

and

the

weights

themselves

to

require

less

drop

distance. |

This

is

the

configuration

which

was

set

up

for

Hortense.

HORTENSE'S

PENDULUM

Two different

pendulums were

available for

the #16 tower

clock. A

four-foot long

one weighing 135

lbs. or an

eight-foot

long one

weighing 175

lbs. The 8

ft. one would

have required a

hole cut in the

floor for the

pendulum to

swing freely in

the bell room

below.

Being twice as

long, its period

would have been

2 seconds--1

second in each

direction. Hortense

had a 1-second

pendulum, so it

was the 4 ft.

one weighing 135

lbs. With

the clock itself

being 54 inches

tall, a 48-inch

long pendulum

wouldn't reach

the floor if

connected to the

clock six inches

or less from the

top.

HOW MUCH DID

HORTENSE WEIGH?

Assuming the

weight given for

the Seth Thomas

tower clocks

diagram seen at

left, they are

describing the

mechanism seen

in the diagram.

They couldn't

give the weight

with all the

attachments

because that

would be

different for

each order.

So it makes

sense that the

weight given

here is for just

what you see

here.

The 4 ft. long

pendulum with

135 lb. weight

seems to be

included in this

"box" because it

is shown along

with the clock

mechanism.

However, an 8

ft. pendulum

might have to be

shipped

separately,

unless it came

apart in two

4-ft sections.

The line about

the dials is

only there to

specify what a

#16 tower clock

can drive.

It was "FOR

ONE dial up to

10 feet [in diam.]

OR FOUR dials of

8.5 feet or

less.

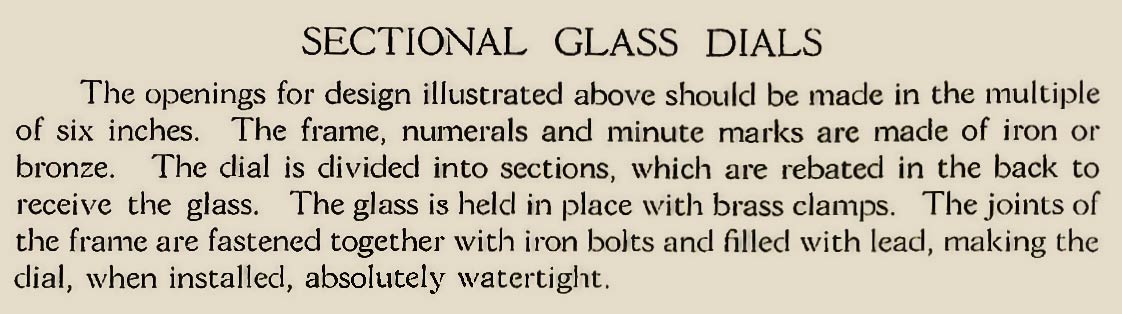

Obviously, glass

dials wouldn't

be shipped in

the same box as

a device such as

seen at left.

They would

require more

protective

framing.

Same goes for

the bell, it's

giving a

suggested size,

not stating that

the bell is in

the same box

with the clock.

So Hortense

weighed about

1,500 lbs.

including the

crate.

This would

appear to have

included the 135

lb pendulum but

not her

bell nor her 35

lb hammer, and

definitely NOT

the four

sectional glass

faces with iron

dial rings (six

pieces per

face).

There is no

mention of the

weights which

drive the clock

and the ones

which power the

strike hammer,

so those must

have been

shipped

separately as

they alone

totaled 1,700

lbs. Then

there is the

weight of the

bell (which

McShane Bell Co.

will provide

below), which

also couldn't

possibly be part

of the approx.

1,500 lb boxed

weight they

describe.

THE

GRAHAM

ESCAPEMENT

George

Graham

(1673-1751)

of

London

was

an

English

clockmaker

and

inventor

and

a

member

of

the

Royal

Society.

He

was

partner

to

the

influential

English

clockmaker

Thomas

Tompion

during

the

last

few

years

of

Tompion's

life.

Graham

is

credited

with

inventing

several

design

improvements

to

the

pendulum

clock,

inventing

the

mercury

compensation

pendulum

and

also

the

cylinder

escapement

for

watches

and

the

first

chronograph.

However,

his

greatest

innovation

was

the

invention

of

the

Graham

or

dead

beat

escapement

around

1715.

Graham

refused

to

patent

these

inventions

because

he

felt

that

they

should

be

used

by

other

watchmakers.

George

Graham

is

said

to

have

modified

the

anchor

escapement

to

eliminate

recoil,

creating

the

deadbeat

escapement,

also

called

the

Graham

escapement.

This

has

been

the

escapement

of

choice

in

almost

all

finer

pendulum

clocks

since

then.

Graham

modified

the

arm

of

each

steel

pallet

so

that

the

lower

portion

of

each

limb

was

based

on

the

arc

of a

circle

with

its

center

at

the

axis

of

rotation

of

the

pallets

(see

Fig.

1).

The

tip

of

each

limb

had

a

surface,

the

angle

of

which,

based

on

force

directions,

was

designed

to

provide

an

impulse

to

the

pallet

as

the

escape

tooth

slid

across

the

surface

of

each

tip.

The

escape

tooth

strikes

the

pallet

above

the

tip

on

the

lower

portion

of

the

limb

(see

Fig.

2),

where

the

escape

wheel

is

rotating

clockwise

and

is

about

to

strike

the

entrance

pallet

on

the

left

side,

above

the

impulse

face.

The

surface

that

the

escape

tooth

strikes

is

the

locking

face,

since

it

prevents

the

escape

wheel

from

rotating

farther.

Info

and

images

below from

Princeton.edu

Animated GIF courtesy of

Wooster Physicists

"Deadbeat Escapement"

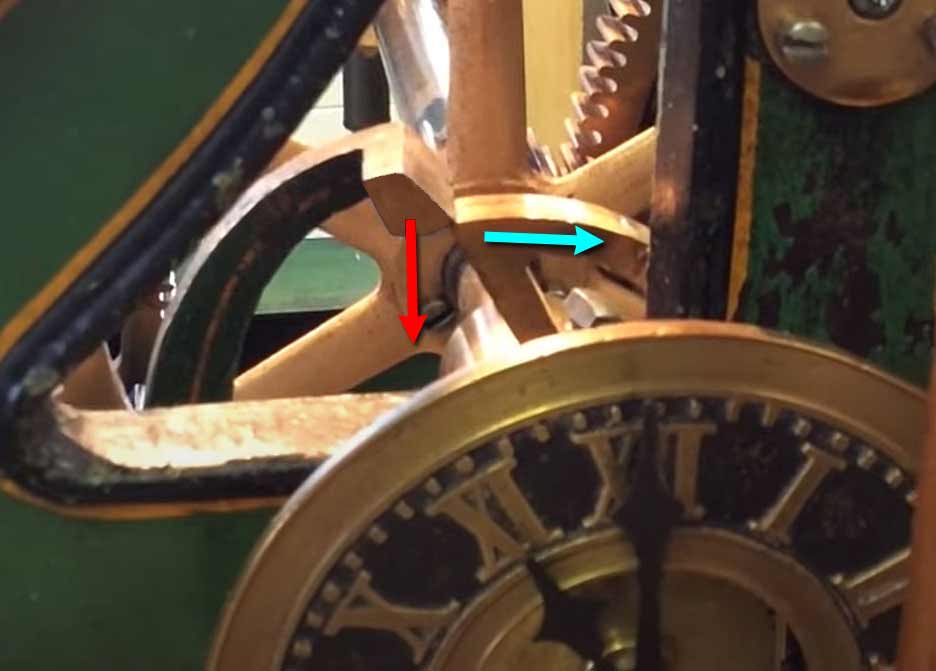

Photo

is

courtesy

of

the

South

West

Museum

of

Clocks

&

Watches

who

beautifully

restored

this

Seth

Thomas

tower

clock

in

its original colors.

|

|

|

Another

fascinating

video from

Trevor

Murphy:

THE FOUR

MAJOR PARTS

OF A TOWER

CLOCK

|

|

|

THIS

IS

AN

OLDER

SETH

THOMAS

BUT

VERY

SIMILAR

IN

DESIGN

TO

HORTENSE.

Just

before

it

chimes

at

11:00,

you

can

see

the

mechanism

that

controls

the

chime

count

at

the

very

edge

of

the

rotating

wheel.,

called

a

"snail."

The

count

mechanism

method

is

called

"rack

&

snail."

This

is

the

critical

part

that

releases

the

striking

train

at

the

proper

time

and

counts

out

the

proper

number

of

strikes.

It

is

the

only

part

of

the

striking

mechanism

that

is

attached

to

the

clock's

timekeeping

works.

Virtually

all

modern

clocks

use

the

rack

and

snail.

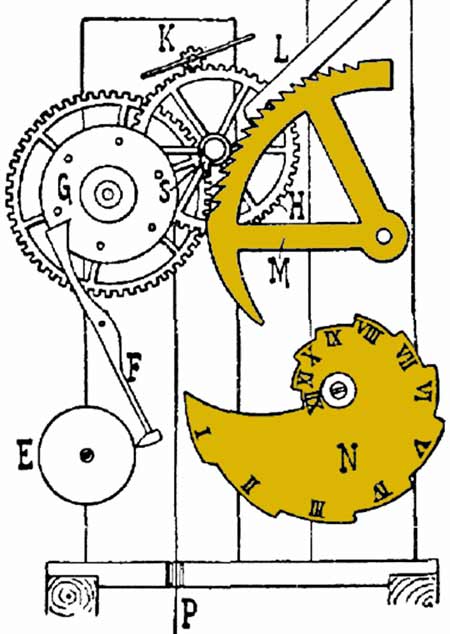

The

snail

(N)

is

usually

mounted

on

the

clock's

center

wheel

shaft,

which

turns

once

every

12

hours.

There

is

also

a

release

lever

(L)

which

on

the

hour

releases

the

rack

and

allows

the

timing

train

to

turn. This

is

the

critical

part

that

releases

the

striking

train

at

the

proper

time

and

counts

out

the

proper

number

of

strikes.

It

is

the

only

part

of

the

striking

mechanism

that

is

attached

to

the

clock's

timekeeping

works.

Virtually

all

modern

clocks

use

the

rack

and

snail.

The

snail

(N)

is

usually

mounted

on

the

clock's

center

wheel

shaft,

which

turns

once

every

12

hours.

There

is

also

a

release

lever

(L)

which

on

the

hour

releases

the

rack

and

allows

the

timing

train

to

turn.

https://www.wikiwand.com/en/Striking_clock

This

video

below

shows

the

striking

sequence

in

action

at

2 min

25

sec.

At

the

rear

of

the

clock

can

be

seen

the

fan

blades

start

spinning

using

the

air

resistance

to

govern

the

rate

at

which

the

hammer

strikes

the

bell.

This

clock

is

equipped

with

electric

motors

to

rewind

the

weights

automatically.

This

is a

different

type

of

escapement

but

it gives

a

good

view

of

how

the

bell-strike

mechanism

works

the

hammer. |

|

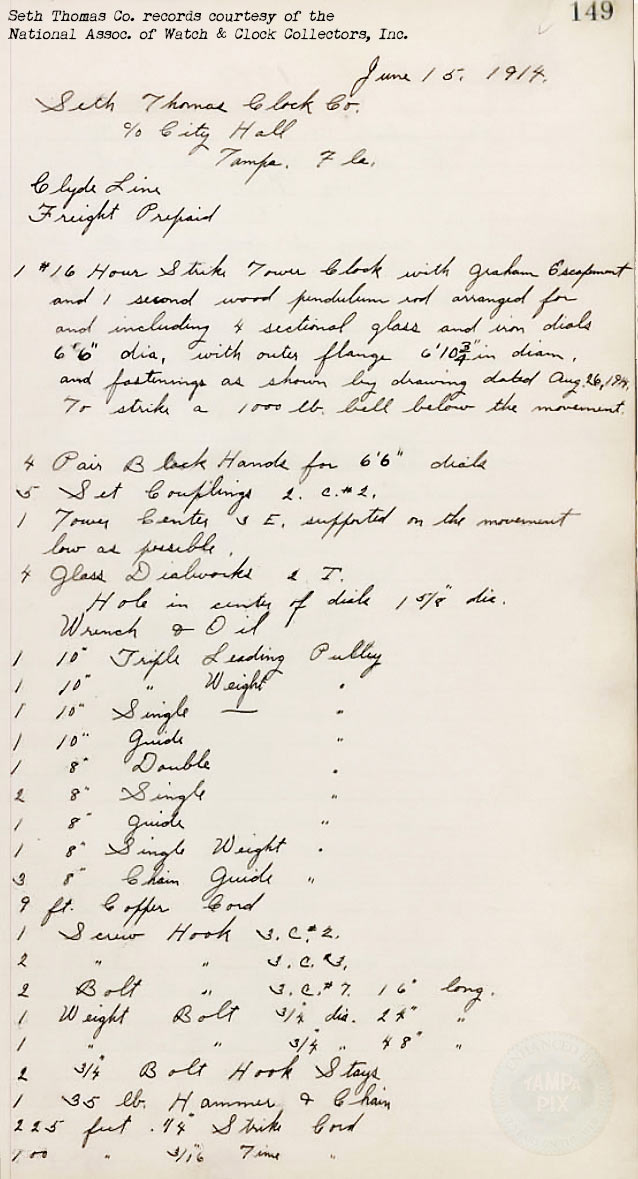

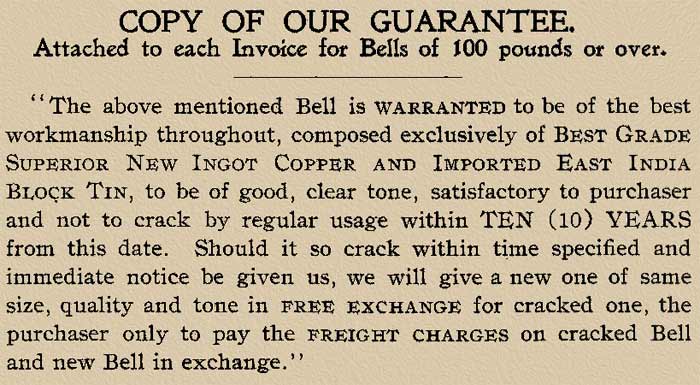

THE BILL

Mouse-over the

image to see it

transcribed.

BILLING DETAIL

The

total

cost

for

just

Hortense

the

clock

herself

was

$675.25

which

consisted

of

the

five

amounts

in

red

above

the

subtotal;

the

clock

alone

costing

$204,

trimmings

$317,

Dials

$120

($30

each),

the

10"

weights

totaling

300

lbs.

to

drive

the

clock $6.75,

and

the

14"

weights

totaling

1,400

lbs.

to

drive

the

strike

hammer $27.50.

The charges for

her bell from

McShane Bell Co.

were $328.04 for

the bell itself

and $11.44 which

may have been

for parts, or

adding the Seth

Thomas mark to

the bell, or the

clapper (which

wouldn't be

used), or any

combination of

these items.

The "Holbrook"

charge might be

for the glass

dials.

The $1080.41

represents the

Seth Thomas

charge of 675.25

and the three

charges of

McShane &

Holbrook.

The total of

1266.72

represents the

1080.41 plus Wechler's

charge. |

For some reason,

it appears that

W. H. Beckwith

was only charged

$1,235.00, a

discount of

$31.72.

This was a 2.5%

discount.

The City

probably paid

him the full

$1,266.72 and

the difference

was his

commission.

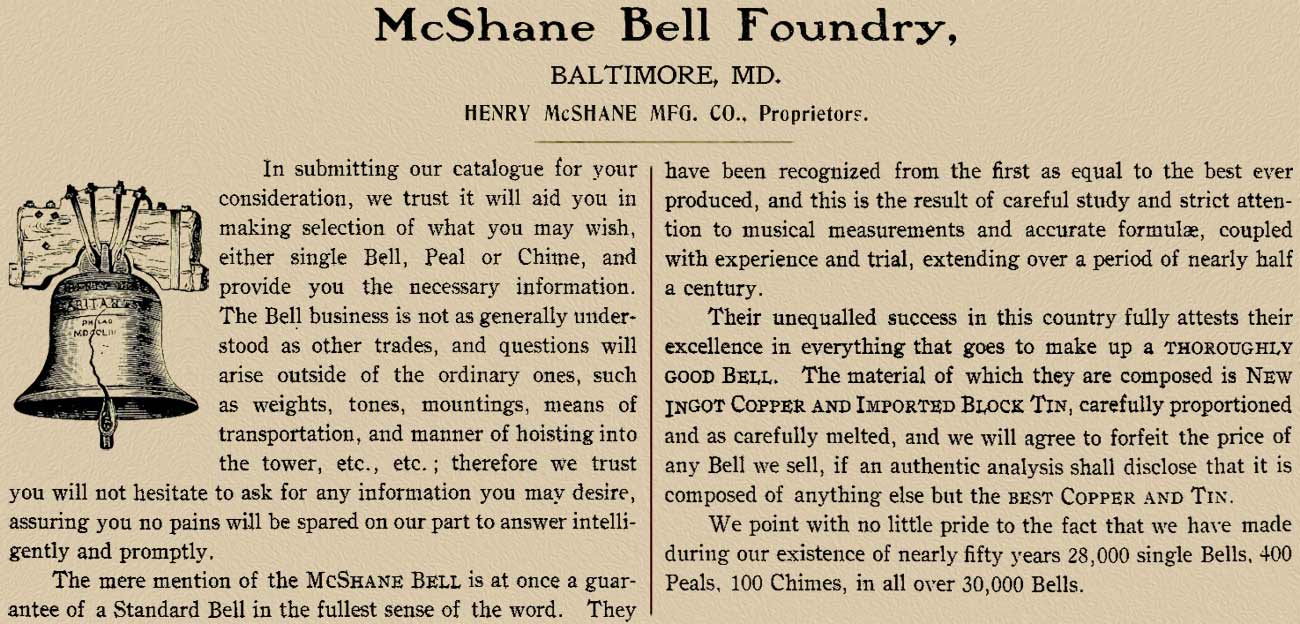

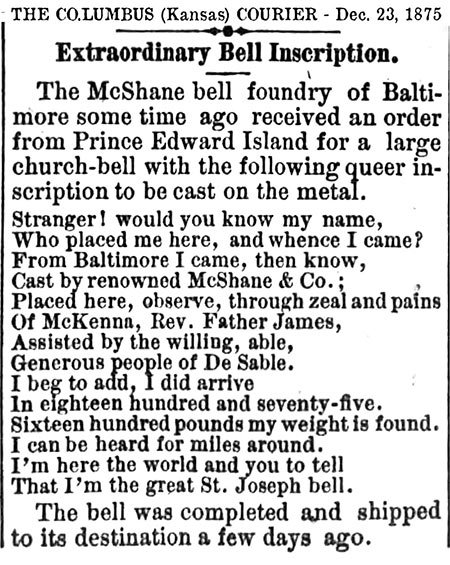

HORTENSE'S VOICE

The melodic

voice of

Hortense was

crafted by

skilled artisans at the

McShane Bell Co.

foundry in

Baltimore, Md.

in 1914.

|

"RING

BEARERS"

|

|

America's

longest running

bell

manufacturer

|

After

162 years in

business, the

longevity of

McShane Bell

Foundry takes on

added resonance.

Photo: Co-owner

William R.

Parker III,

left, with head

service tech Joe

Bennett. After

162 years in

business, the

longevity of

McShane Bell

Foundry takes on

added resonance.

Photo: Co-owner

William R.

Parker III,

left, with head

service tech Joe

Bennett.

Christopher

Myers Photo courtesy

of

2018 article in

Baltimore

Magazine

Henry McShane

was a teenage

lad from County

Louth, Ireland,

when he

immigrated to

Baltimore in

1847. He found

employment in a

brass factory

and took a shine

to the work.

Nine years

later, in 1856,

he struck out on

his own, opening

the original

McShane Bell

Foundry at

Holliday and

Centre Streets.

Initially, the

company made

pipes and

plumbing

fixtures, in

addition to

bells. But soon

its bells—with

their graceful

contours and

clear ringing

tones—overshadowed

the company’s

other output. In

particular, the

company became

known for its

peals (sets of

seven or fewer

bells) and its

chimes (sets of

eight or more

bells).

By 1873,

business was

booming, so much

so that McShane

opened a second

facility near

where The

Baltimore Sun

building now

sits on Guilford

Avenue (then

called North

Street).

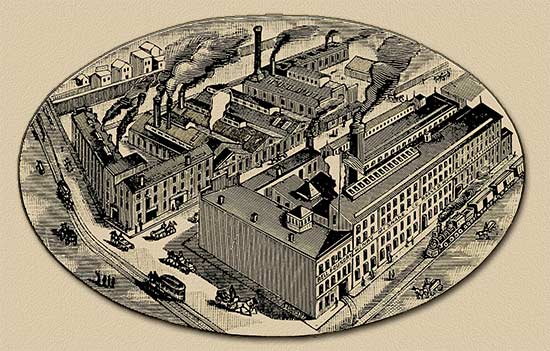

An illustration

of the North

Street complex

from a company

catalogue in

1900 gives some

idea of the

scale of the

operation, which

employed some

200 workers. The

image shows

several

smoke-spewing

chimneys puffing

away while

horse-drawn

carriages,

streetcars, and

a train whiz by.

Inside, the

catalogue boasts

that, “space

will not permit

of our giving

full detail of

all the chimes

and peals we

have made,” but

does go on to

list 15 pages

worth of

recently

completed

projects,

including chimes

in Key West,

Chicago,

Detroit, and

Ontario, Canada,

and peals in

locations

ranging from

Boston to Buenos

Aires and New

Orleans to New

York City.

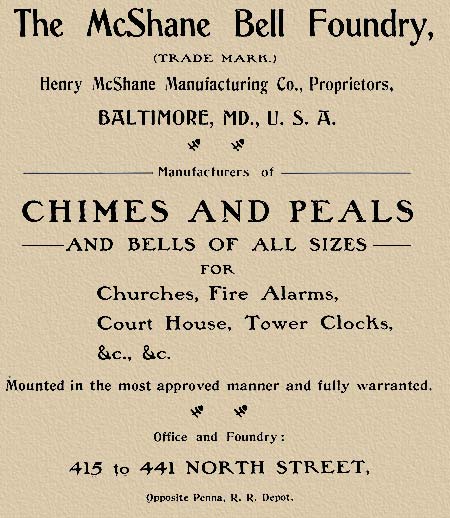

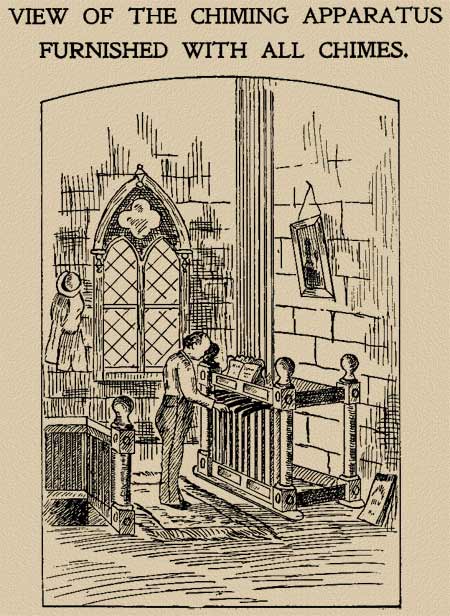

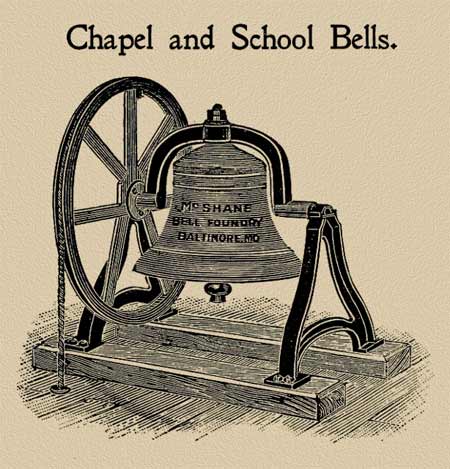

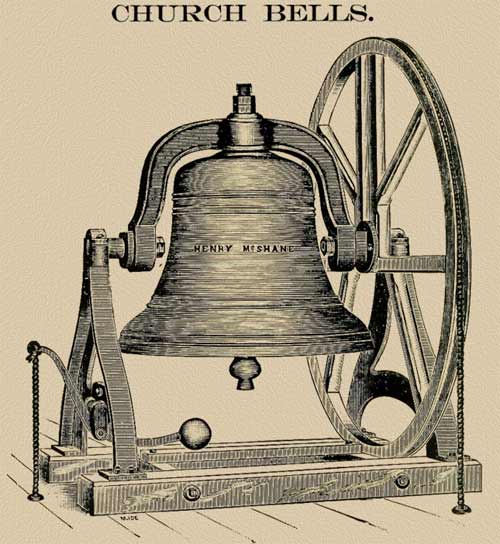

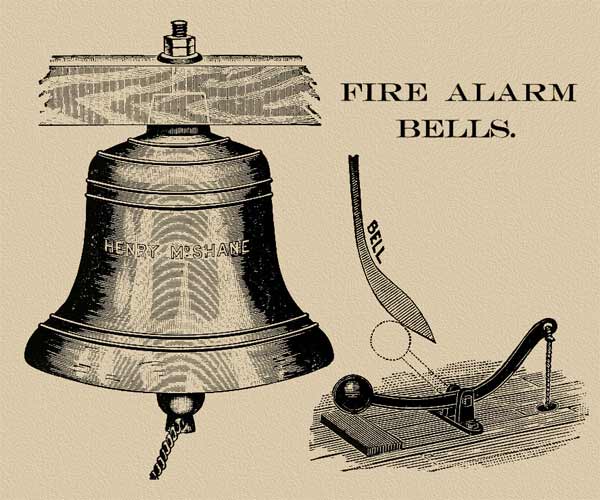

Images below are

from the above

mentioned McShane

Bell Foundry

catalogue printed

1900 found at

Internet Archive.

The McShane Bell

Foundry factory

complex located

at 415-441 North

Street (Guilford

Avenue),

Baltimore, MD.

Cropped from

page 53 in a 1900

McShane products trade

catalogue. Digital image

available

through the

Internet

Archive.

Many of

McShane's bells

are at many Baltimore

sites, too.

Though not

listed in the

1900 catalogue,

the company’s

most famous

local bell is

the “Lord

Baltimore.” Cast

in 1889, the

7,100-pound

beauty still

sits atop

Baltimore’s City

Hall and chimes

on the hour.

Other prominent

McShane bells

sound out from

perches at

Towson

University, The

Maryland State Boy choir, and

The Johns

Hopkins

University’s

Homewood campus.

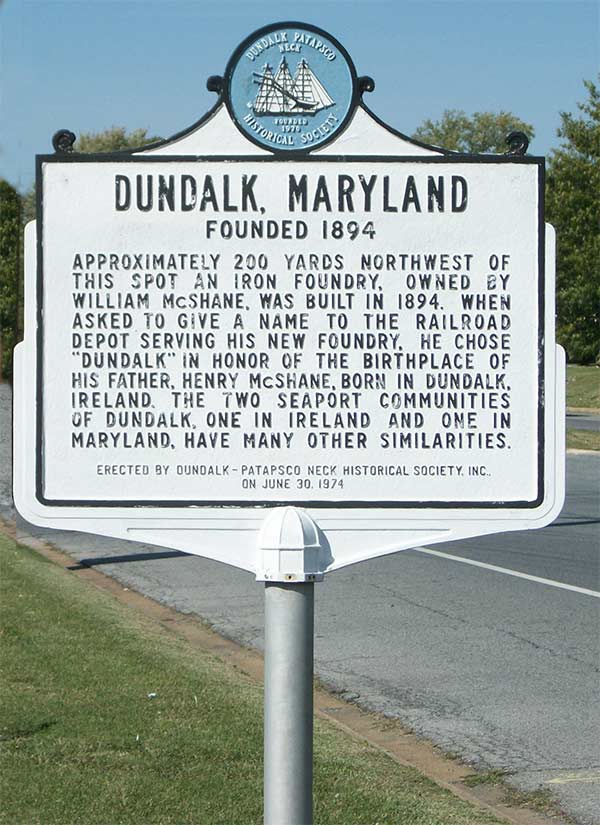

After a fire

damaged part of

the North Street

foundry in 1893,

McShane decided

to move at least

part of the

company’s

operations to an

undeveloped plot

along the

Patapsco east of

Baltimore. When

the railroad

followed the

foundry out that

way two years

later, officials

asked McShane to

provide a name

for the new

depot. McShane’s

son William

James, then the

company’s vice

president, chose

to honor his

father’s Irish

hometown,

nailing a sign

to a tree near

the train

station that

read "Dundalk.”

Because many

records were

destroyed in the

Great Baltimore

Fire of 1904,

relatively

little is known

about the

company in the

early 20th

century. The

timeline becomes

clear again in

1933, when a

family by the

name of McAleer

sold the

business to

William R.

Parker Sr.

“My grandfather,

back in the

1930s, had a

tool and die

machine shop

next to the bell

foundry,”

explains Parker

III. “He was

just fascinated

by the bell

business. . . .

When [the

McAleers] took

ill, my

grandfather

stepped in and

bought the

business. It has

been in my

family ever

since.”

In 1946, after

yet another

fire, Parker Sr.

and his wife,

Edith Meyers—who

ran the front

office—moved the

foundry to a

two-story

structure on

East Federal

Street, near

Penn Station. In

1965, Parker

Sr.’s eldest

son, William R.

Parker Jr.,

joined the

family business.

And in 1979,

after the

company lost its

lease on the

Federal Street

property, Parker

Jr. moved the

foundry to a

warehouse in

Glen Burnie “on

a temporary

basis,” figuring

at least he’d be

closer to the

family home in

nearby Pasadena.

Though the story

of McShane Bell

Foundry is

marked by near

constant change,

there has been

one through

line: an

unflagging

devotion to—and

pride in—the

company’s

superior

craftsmanship.

This starts with

Henry McShane’s

original—and

somewhat

eccentric—bell-making

recipe.

The McShane Bell

Foundry is now located

in St. Louis,

Missouri. Over the

past 150 years,

the firm has

produced over

300,000 bells

for cathedrals,

churches,

municipal

buildings and

schools in

communities

around the world

- including the

7,000-pound bell

that hangs in

the dome of

Baltimore's City

Hall. It was

featured on an

episode of the

Discovery

Channel's Dirty

Jobs..

In 2019, the

company moved

its headquarters

from Glen Burnie,

near Baltimore,

Maryland to St.

Louis Missouri,

as it

centralized its

manufacturing

and shipping.

BELOW FROM

THE McSHANE

WEBSITE:

"Our bells

are produced

using time

honored

techniques

and with

state of the

art foundry

craftsmanship

and

technologies

to produce

bronze

church bells

that are as

beautiful to

hear as they

are to view.

All our

bells come

with state

of the art

mechanical

and

electrical

ringer’s

systems for

both

swinging and

stationary

bells. Our

state of the

art

equipment is

what helps

produce

their

beautiful

unmistakably

McShane

tones. Our

goal is

simple: to

produce the

best

sounding

bells with

the most up

to date

ringing

systems for

our

customers.

We approach

each project

big or small

as if it’s

our only

project.

This

accountability

and

attention to

details for

our

customers is

what sets

McShane Bell

Foundry

apart. Our

other

services

include

consultation,

inspections,

annual

maintenance

contracts,

and bell

towers.

Basically

McShane can

handle your

church bell

projects

from start

to finish

with

outstanding

results."

Some of the

above info is

parts of a

2018 article

courtesy of

Baltimore

Magazine,

Wikipedia

and the

McShane website

|

| |

|

|

|

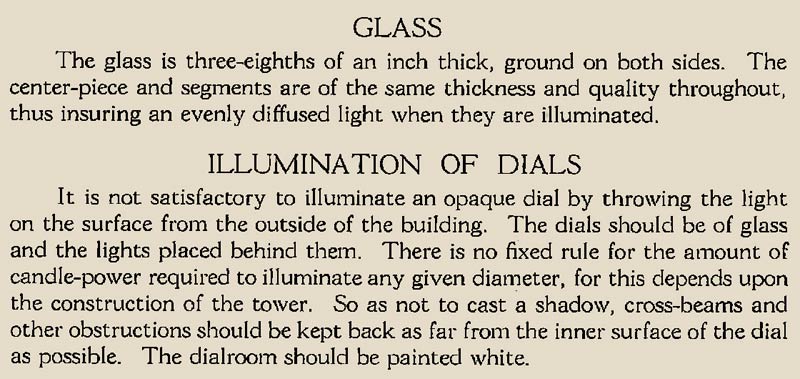

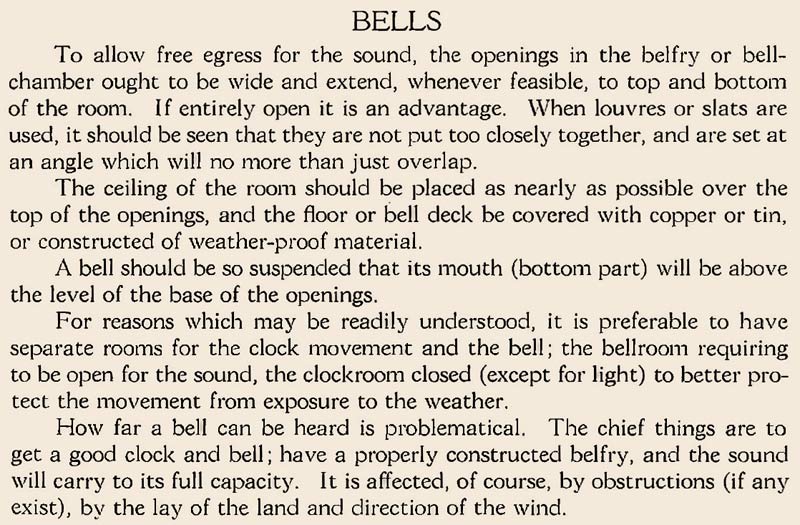

Below

from

Seth

Thomas

Co.

Tower

Clocks,

1911,

recommends

the

bell

room

be

separate

from

the

clock

room,

either

completely

open

all

around

or

with

louvres

or

slats

spaced

not

too

closely

together

and

just

so

they

barely

overlap,

the

floor

be

covered

with

copper

or

tin

or

some

other

weather-proof

material.

The

bell

mouth

should

be

above

the

level

of

the

base

of

the

wall

openings.

The

clock

room

should

be

sealed

from

the

weather. |

|

|

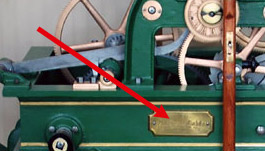

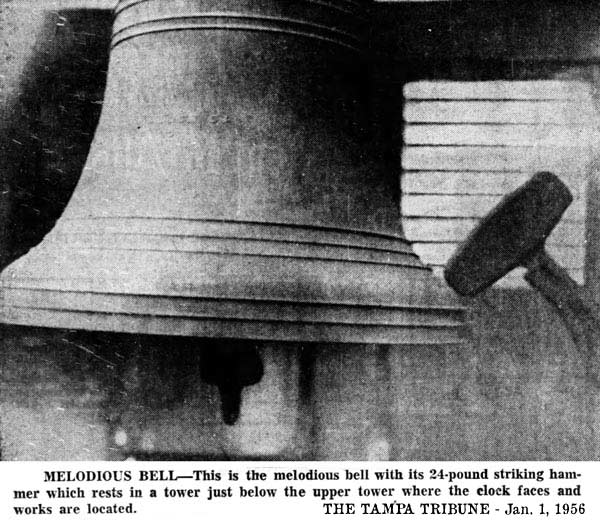

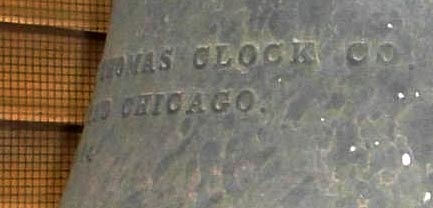

Photo below from

Apr. 27, 1989

Tampa Times

article shows

the McShane

mark.

Since

only

"Thomas

Clock

Co."

is

visible,

the

second

line

probably

reads

"New

York

and

Chicago,"

the

location

of

their

corp.

offices

at

the

time.

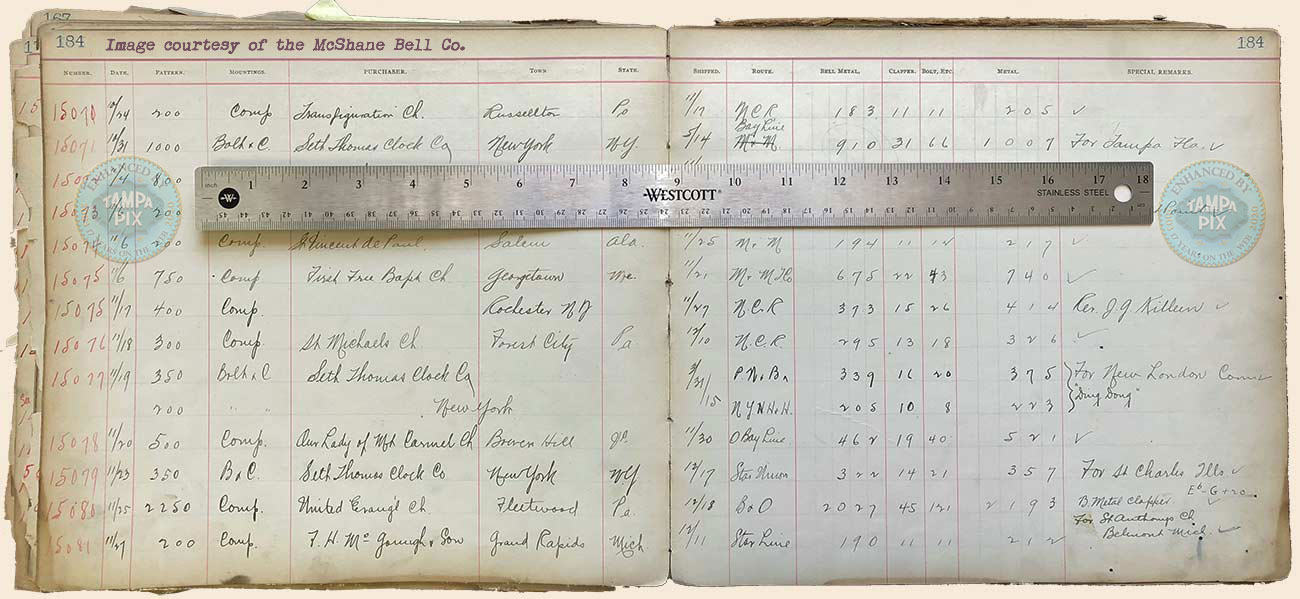

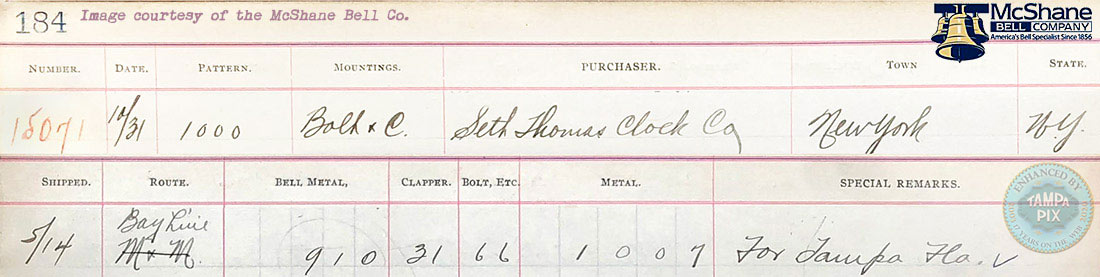

McSHANE BELL

CO. RECORDS

Special

thanks to the

fine sales team

at McShane Bell

Co. for

going beyond

just answering

TampaPix's

question by

sending this

amazing image.

There is a close

up of the entry

for Tampa

further below.

|

Tampapix

contacted the

McShane Bell Co.

in late May 2020

asking if it was

possible that

Seth Thomas

Clock Co. added

their mark to

our McShane

bell, and

included the

photos of our

City Hall bell

showing the

McShane mark and

the Seth Thomas

mark.

Their response

was prompt, the

next day the

McShane sales

team responded

with the above

incredible image

showing Seth

Thomas' order

for our 1,000

lb. City Hall

tower clock bell

on Oct. 31,

1914. They said

once a bell has

been made a

second mark

cannot be added.

They put their

mark on it and

whatever mark

the customer

requests on the

other side at

the time the

bell is made. McShane has made

bells that even

have a person's

name on it, such

as someone being

honored like a

mayor, governor,

or military

officer.

If the City of

Tampa would have

thought to name

our clock

"Hortense"

sooner, they

could have had

it put on the

bell!

|

|

Our bell was

shipped via Bay

Line to Seth

Thomas Clock Co.

in New York on

May 14, 1915.

.jpg)

|

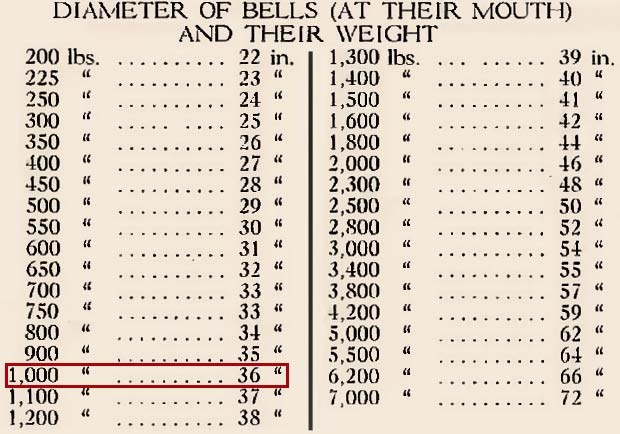

Hortense's bell

weighs 1,000

lbs. and has a

36" diameter

mouth. She

is about as tall

as she is wide.

The hammer

weighs 35

lbs and is

connected to the

clock by a chain

drive.

The Liberty bell

is 46 inches in

diameter at the

lower rim and

weighs 2,080

lbs.

Though it is not

used, Hortense's

bell has a

clapper with a

ring to tie a

rope or chain.

It could be used

to ring the bell

manually if the

hammer system is

out of order.

|

|

1915 CITY

HALL -

COUNTING THE

COST IN 2020

DOLLARS

(Values

obtained

from US

Inflation

Calculator.) |

|

| |

YE TOWNE

CRYER'S $150

DONATION

to the old

folks home

in 1913

would be

like

$3,291

in 2020.

|

| |

|

CITY HALL

total

appropriation

$300,000

in 1914

would be

like

$7,764,330

in 2020

includes:

LAND

purchases:

$

65,000

tot. in

1914 is

like

$1,682,272

in

2020 |

| |

|

BUILDING

COSTS

$235,000

in

1914 is like

$6, 082,058 in 2020 |

|

| |

|

HORTENSE:

Seth

Thomas clock

bill was

$1,266.72,

in 2020 dollars

that's

around

$32,791.

Includes

$339 for

McShane

bell, would

be like

$8,773

in 2020. |

|

| |

|

BECKWITH'S

DISCOUNT

or HIS

PROFIT:

$31.72

in 1914 is

like

$821

in 2020. |

|

|

|

1915 CITY

HALL -

COUNTING THE

COST IN 2022

DOLLARS

(Values

obtained

from US

Inflation

Calculator.) |

|

| |

YE TOWNE

CRYER'S $150

DONATION

to the old

folks home

in 1913

would be

like

$4,434

in 2022.

|

| |

|

CITY HALL

total

appropriation

$300,000

in 1914

would be

like

$8,779,650

in 2022

includes:

LAND

purchases:

$

65,000

tot. in

1914 is

like

$1,902,257

in

2022 |

| |

|

BUILDING

COSTS

$235,000

in 1914

is like

$6,877,392 in 2022 |

|

| |

|

HORTENSE:

Seth

Thomas clock

bill was

$1,266.72,

in 2022 dollars

that's

around

$37,071.

Includes

$339 for

McShane

bell, would

be like

$8,773

in 2022. |

|

| |

|

BECKWITH'S

DISCOUNT

or HIS

PROFIT:

$31.72

in 1914 is

like

$928

in 2022. |

|

|

|

|

|

HISTORY REWRITTEN - Tampa's Old

City Hall Clock

When, Why, and How It Really

Happened

|