Walter Scott Burgert

Walter was born on Dec. 9, 1879 in Cincinnati, Ohio. After moving to Jacksonville with his family and living for a number of years there, Walter and his father S. P. went back to Cincinnati for a short time, starting another studio there. But soon, they returned to rejoin the family in Jacksonville and subsequently move to Tampa in the late 1880s .In 1927 Harold C. Burgert (Harry's son) recalled that in 1900 Walter and his older brother Jean "opened a studio in the Whaley Building in Tampa, which organization developed into the present firm of Burgert Brothers, commercial photographers." Tampa's 1901 city directory shows that Walter worked at the photographic firm of S.P. Burgert and Son (along with Willard and Jean), and that he boarded at 803 6th Avenue, where Samuel and Jean also lived. The 1903 directory shows that Walter and Jean ran "Burgert Bros." photographers at 814 1/2 Franklin Street. Jean is also listed as an employee of Burgert and Sons, though not Walter. Walter and Jean apparently boarded at the same locale, 506 Madison Street, a short walk from their studio. Thereafter Walter was in and out of the photography business. Walter seems to have been a restless person, as were Willard, Jean and Harry in their own ways. But unlike them, Walter never appeared to have attained any measure of great success in the jobs that he attempted outside commercial photography, nor to have achieved any special recognition within the profession. His dreams led him to drift into areas where his knowledge or experience could not sustain him for very long or enable him to find fulfillment. He fantasized about becoming a doctor and actually dabbled in chemically producing and marketing home remedies such as milk of magnesia. He also experimented with commercially manufacturing oxygen, but none of these endeavors bore the fruit of success he seemed to long for. He also had many other longings.

Walter worked as a traveling photographer in 1910 and along with Jean, was part of the first Burgert Brothers firm. When he registered for the WW1 draft in July, 1918, he lived in Richland, Pasco County, an area somewhat halfway between Zephyrhills and Dade City. Here, Walter worked as a farmer, but this ended in bankruptcy.

Photography appears to have been for Walter a sure, yet unsatisfying way to earn his living. He worked at the trade sporadically during the first three decades of 1900. In the early 1920s he owned and operated Paris Studio into the 1930s, a portrait studio in Ybor City which was also his home, at 14th Street and 9th Avenue. Later he moved to Ybor City's main business thoroughfare on the 1400 block of 7th Avenue. City directories list 1512 10th Avenue as his home and photography business address from 1934 until his death on Sept. 1, 1943. He and Clymene had no children.Although some of the living Burgert family's recollections of him describe his inability to achieve the success that marked the lives of Willard (though he spent almost as much as he made), Jean, Harold and Alfred, the family did not perceive him as a failure, and certainly not as a black sheep. He was seen, rather, as one who did not place his mark upon the community as sharply as did his brothers.

Albert John Burgert

Albert "Bert" Burgert was born April 1, 1887 and was a twin brother to Alfred Burgert, but had the misfortune as a youngster of sustaining a head injury after having a nursemaid drop him. This gave him a bad bruise, probably the result of a fracture so severe that even in later life family members could feel his pulse throb by touching his skull. The family felt it was this accident that damaged and never permitted Bert to develop his full intelligence. He functioned well physically, but mentally he was always somewhat childish and adolescent. Although Bert initially worked in a grocery store as a clerk, he soon joined his brothers and their father in different jobs centering around the photography profession. In 1908 he worked as a finisher at brother Willard's Tampa Photo and Art Supply. He later worked there as a shipping clerk. Burt's nephew Thel described his uncle a handy assistant who mixed chemicals, laid out prints on the ferrotype tins to give them a high gloss, and made deliveries. He was a big help--once the picture was taken, the developing, printing and binding of photographs could be turned over to him. On Oct. 23, 1912, Bert married Florida native Drewtina Douglas, a daughter of Blanche Douglas. Will also employed Drewtina as a sales clerk at his shop. Around 1928, he and Drewtina divorced.Good-natured and fun-loving, Bert was also a magnificent pianist, and would perform on excursion boats that traveled from Tampa to nearby Pass-a-Grille. He would play the piano for hours on these cruises, delighting the passengers.

Later in life Bert became disoriented. By 1935 he had to be hospitalized at the Florida State Hospital in Gadsden County, FL, where he lived out the rest of his years, passing away perhaps from his brain disorder, aneurism or brain tumor in 1945 at age 58.

The Burgert Brothers at the Tampa Bay Hotel, 1914 L to R: Al, Bert, Willard, Harry, Walter, Jean. Photo courtesy of Hal Burgert, III

From the Burgert Bros. collection at the Tampa-Hillsborough County Public Library System

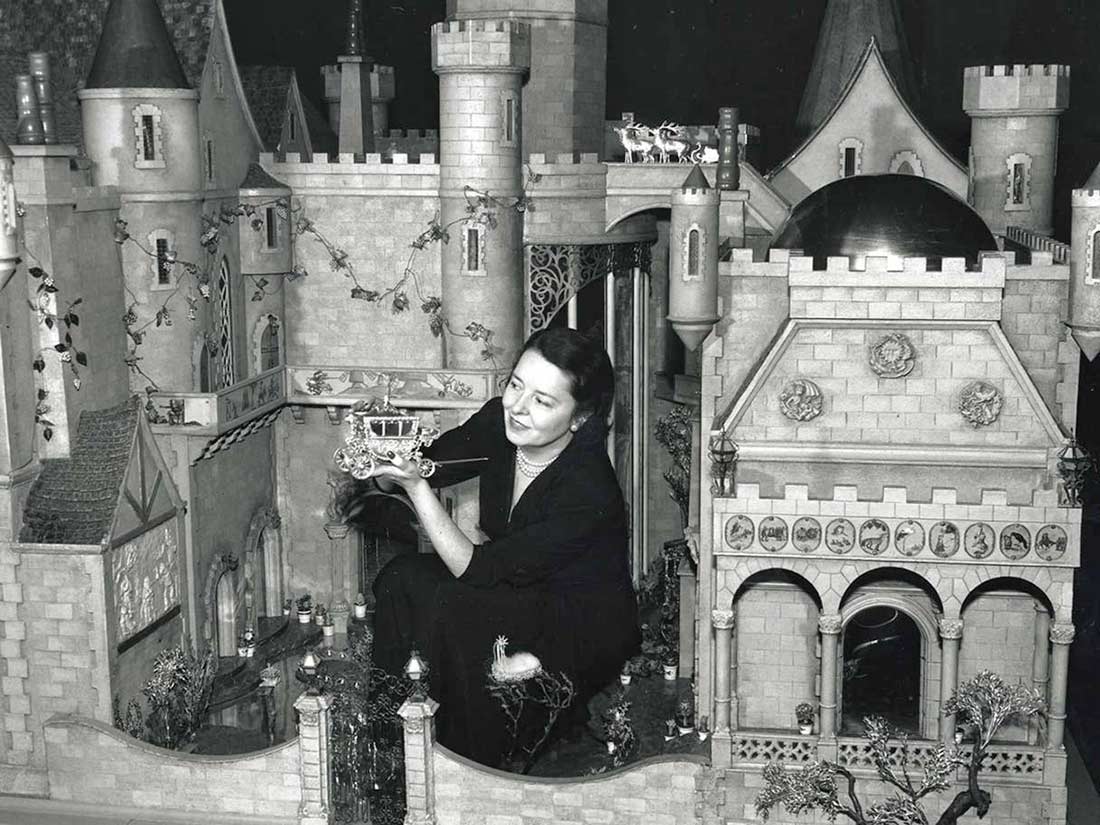

See more photos on the set of "Hell Harbor" State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

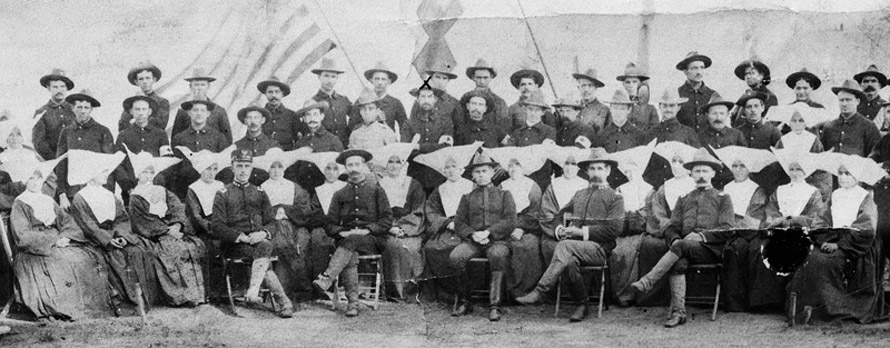

World War 1

World War 2

The Burgerts also opened a portrait studio near Drew Field that was very lucrative because the boot camp at the field had at some times over 150,000 men, and the population of inductees who trained at the camp changed every six or seven weeks. Most of the men wanted portraits for their mothers, wives and girlfriends, and Burgert Brothers took many of these, installing an operator at that studio who took the shots and sent them back to the Burgertsí Jackson Street studio for processing.

Read about Drew Field at TampaPix

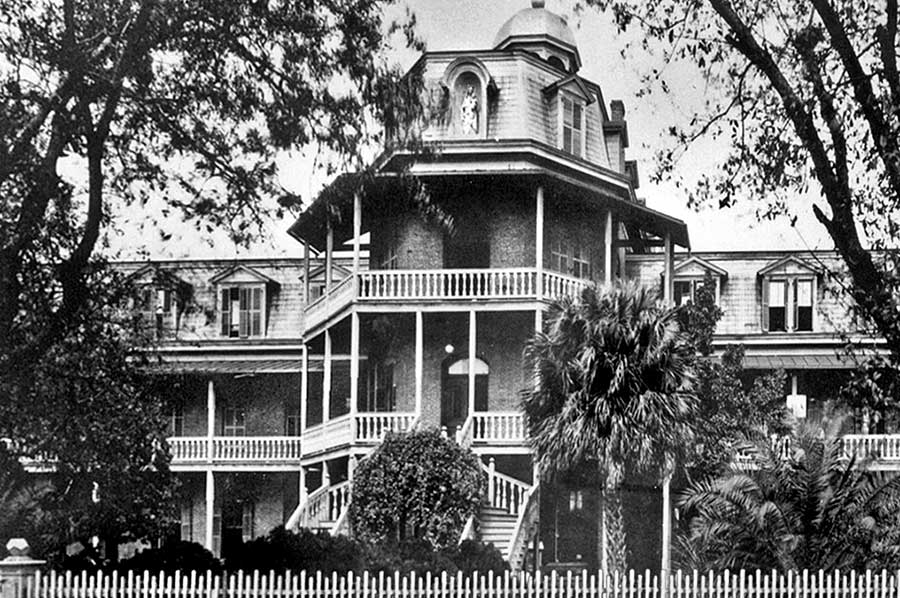

Only a small amount of product shooting was done in the studio--for example, pictures of bottles or cigarettes--for print advertisements. Most of the commercial work was done on location and outdoors in black and white. Al had a few favorite locations for his commercial work: The Tampa Terrace Hotel, a really beautiful place in downtown Tampa, the Palma Ceia Golf and Country Club; the Tampa Yacht Club; Bayshore Boulevard, where there were large, new houses, and stately trees lining the Bay; and Tarpon Springs with its colorful sponge fishing docks.

Al developed the crisscross record-keeping system. Every photograph

was recorded by the negative and by the topic. Within a matter of

minutes any negative in a collection of thousands could be located. This

system reflected Alís meticulous ways. He did not see himself as a

chronicler of history, but simply needed an efficient retrieval system

to keep his business straight. There was a strong demand for reprints of

old photographs. The standard charge was $1.00 for a linen-backed

photograph that added to the life and durability of the photograph and

made it easy to bind into an album. Photo Retouching

One of the more interesting jobs at Burgert Brothers, and one in which they always seemed to have an expert, was photo retouching. From the early 1940s until the close of World War II, Roberta Lucas worked at this craft in the studio and at home. Photographic retouching involved removing from a picture whatever was not wanted and adding items the photograph needed. A street view might require the retoucher to remove adjoining buildings or pedestrians from the sidewalk, and then add such features as trees, shrubs or a paved street to highlight and accentuate the scene. These items were added by drawing them in, and this is where Roberta Lucasí skill as an artist-she studied art at Oglethorpe University-came into play. Her skills were used to outline, highlight, accentuate or modify various features in the photograph, or to add new features. For one series of photographs taken in the mid-1930s, Al Burgert accompanied a friend, George Brown, on a hunting trip to the Crystal River area, taking along his camera but not a gun. He snapped some seemingly random scenes and later gave these finished, unretouched pictures to Mr. Brown. But he also used one of the photographs in a sales campaign for X-Cel dog food after having his retoucher stiffen one dogís tail and shift a tree, presumably to make a more effective picture.

Move your cursor on the photo to see the X-Cel dog food ad

Thel Burgert claimed that Burgert Brothers had what he called the first reliable charge for photography work in the area and that their rate schedule was then replicated throughout the surrounding country. On a photography assignment the first half hour of driving time was free, but after that the Burgerts charged either for the time or the mileage. The first photograph of a scene would cost a certain amount, and for every duplicate of that scene the cost would be reduced depending upon the quantity ordered. The standard fee they established early in their operation was $4.50 for an eight-by-ten. The Burgerts also charged waiting time. If the crew arrived at a location and the customer delayed the shooting, the customer was billed for the lapsed time.

The Burgert Brothers believed that to make quality photographs the best equipment available was needed. They operated on the principle that a poor lens made a poor picture and a high quality lens made a sharp picture, and reliable equipment eliminated a lot of work and trouble. Consequently (at least early in their careers) they always tried to purchase the most up-to-date equipment available, even though selection was sometimes limited.

They had, by the 1940s, at least three 8" x 10" box "View" cameras, three Speed Graphic press-style cameras that used 4 x 5 film, and one Cirkut camera. In addition to these they owned a variety of lenses--Wollensak, Bausch & Lomb, Zeiss, Tessaric and Unar. The Wollensak would be used, for example, for copying and for wide-angle outside views, and the other lenses for various other foci and distances.

The Burgerts were the only commercial studio in town with the Cirkut camera, which they seem to have possessed from their earliest days in the business. This instrument would take a photograph 7-10 inches high and from 2-5 feet long. It was used for group shots, banquets and panoramic views. People would line up in a semicircle so that every person was the same distance from the camera. As the Cirkut camera gradually rotated, the photographer could take a sweeping picture of almost 360 degrees. The photographer would wind up a clock motor, and the camera would slowly swing around the semicircle exposing the film as it moved along. The cirkut camera gradually went out of use as the type of film it needed was discontinued, and the wide-angle and ultra-wide-angle camera lenses were introduced. The camera the Burgerts used might have been manufactured by Century.

1920 Cirkut camera panorama photo

The brothers also owned a movie camera called the Devry. It was used to make commercial shorts for the movie theatres. They had contact printers for 8" x 10" pictures and Cirkut negatives, and Kodak enlargers for the smaller 4" x 5" film. Among the other equipment were developing trays, washers and dryers. A lot of the equipment was Eastman Kodak.

Al Burgert and his camera on the Burgert Bros. truck, 1935

They also made a special camera for aerial shots. They took parts from an Araflex and other cameras and reinforced the bellows so that air currents would not tear the camera apart as they shot from the open cockpit. The Burgerts would set the camera at a fixed altitude so that their coverage of highway construction, real estate and groves came out clear.

Photographic Supplies Most photographic supplies were ordinarily not a problem, and the Burgerts were careful whenever possible to have ample stock of whatever was needed at hand. The studio purchased its supplies in bulk from Tampa Photo Supply, and there was one room in which a large inventory of supplies was always stacked up. They tried to keep at least one monthís supply of paper and film on hand. This meant the Burgerts had at least 1,000 sheets of paper in ready supply. Even though Tampaís climate was very hot and humid, the paper and film never had to be refrigerated, only stored in a darkroom. These supplies usually had a one year expiration time. When materials were in short supply, photographers had to improvise; for example, by cutting down 8" x 10" to 4" x 5" pieces because the smaller film size was difficult to obtain, or cutting down 4" x 5" to 2" x 2 1/2." Another reason film was cut was that the silver used to coat the negatives was in tight supply and expensive.

Removing Wrinkles The tools of the retouching trade were for Roberta Lucas a lead pencil, etching knife, magnifying glass, and creamy colored viewing board. The retoucher would place a negative on the work board with a magnifying glass over it. As light was directed upward through the glass viewing board, the retoucher would work on the negative. Further details of the retouching procedure depended in part on the chemicals that had been used to process the negative and on the condition of the negative: the slicker the negative, the softer the lead in the pencil, for example. A good photographic retoucher was indispensable to a successful photographic business. The retoucher could remove blemishes caused by chemical spots and dust, repair crack damage caused by old age and carelessness, and remove a personís wrinkles. Customers frequently brought in old prints for repair or fixing up. A family might bring in an old Civil War photograph and want something removed, like a carriage, or they might want a person highlighted by taking others out of the scene. The retoucher commonly had to draw on parts of a photograph, and these features would be built up progressively over stages. A dress might be torn, hand missing, and these items had to be taken care of. The many thousands of pictures for which the firm of Burgert Brothers was responsible reveal a corporate creative entity that produced superb commercial photography with never a hint of pretentious or staged artiness. If they were artists, they were so because of the consistently high quality of the craft they practiced with care and dedication. There is no indication that they ever read art-in-photography books. They seemed never to pose people strangely in their pictures or to wait until people arranged themselves in obviously striking patterns; they did not photograph buildings from odd angles; they appeared not to seek out odd settings for their images, nor to take photographs under weird lighting conditions; or depict momentarily grotesquely juxtaposed objects. Almost invariably their pictures demonstrate straightforwardness, naturalness and clarity.

Historic Enterprise The Burgert's seemed never to have thought of themselves as anything other than commercial photographers, and their aim was to reproduce images that looked like the real thing, undecorated and unmodified. The corporate entity of Burgert Brothers apparently never thought of itself as engaging in either a historic or artistic enterprise, but the photographs Burgert Brothers produced, and transmitted to posterity, demonstrate historic and artistic awareness. The Burgert Collection at the Tampa-Hillsborough County Public Library, Tampa can be searched here Collection History After the Burgert Brothers Studio closed, their photographs and boxes of their negatives (including some plates dating back to the mid 1880s that were originally part of William Fishbaugh's collection), changed hands a number of times. Sometimes stored in someone's attic, and finally were stored in a tin-roofed garage in South Tampa.When Al Severson became the co-owner and head of the firm in the 1940s, he gained control of the firm's facilities, equipment, and vast collection of negatives. Around that time, historian and Ybor City native Tony Pizzo purchased one hundred of the negatives that documented his hometown. By 1965 the rest of the collection had made its way into the offices of Carlton Trimble, a Tampa businessman. Allen Morris, the curator of the state photographic archives, was in Tampa for a legislative caucus when he heard about the collection and sought out Trimble. Over the next year, Morris periodically examined Burgert negatives and selected those he found noteworthy to purchase for $3 each. Morris gradually purchased approximately 500 negatives for the State Archives in Tallahassee. After a 1967 conviction for producing and distributing pornography, Trimble sold his collection to Henry Cox, president of Tampa Photo Supply. By chance, Cox met local historian Hampton Dunn, who recognized the priceless value of the archive as a record of Tampa history. Dunn paid Cox $500 for an unspecified number of the negatives, some of which were published in a book of Tampa photography entitled Yesterday's Tampa. At that time, Cox offered the remainder of the collection to Morris for $10,000. The state could not afford that price. Dunn and Raymond E. Bunch, the owner of a local photography store, used community pride and the possibility of a tax write-off to convince Cox to part with the collection for $2,000. In 1974, the Tampa-Hillsborough County Public Library, with the help of a volunteer support organization, the Friends of the Library, bought the collection (and fourteen handwritten ledgers listing the 70,000 negatives with identifying numbers and simple descriptions,) so the the Burgerts' photographs would be accessible to library customers. Many negatives were destroyed by heat, humidity and rain. To forestall further damage, the Library began the task of transferring the nitrate and cellulose acetate images to modern safety film. Aids by grants received in 1988 and 1992 from the National Historic Publications and Records Commission, and funds from the Library System's budget, the Library has preserved nearly 15,000 of the endangered 8" x 10" images.To date, over 15,000 of these negatives have been developed, digitized, and electronically indexed for the library's website. They are kept in the History & Genealogy Department of the John F. Germany Public Library in downtown Tampa. With Federal grants, library budget funds, and Friends projects, they have been transferred from nitrate-based film to modern safety film. The scanning project for online access, financed by the Frank E. Duckwall Foundation, continued to make hundreds of the images available online each month. This ever-growing collection is an invaluable source for students of Ybor City history and an excellent realization of the possibilities of digital image preservation and distribution. Nearly 15,000 images, and perhaps 35,000 precious negatives remaining unprinted in the collection, chronicle the history of the Tampa Bay area as it faced wars, natural disasters, economic booms and busts. The images offer a view of a community at work, from cigar factories, sponge docks and strawberry fields, to grocery stores, service stations and bank lobbies. Many of the photographs also depict a community at leisure, enjoying a day at the beach, participating in local celebrations, attending the Florida State Fair or playing favorite games such as golf, tennis, shuffleboard or checkers. This extraordinary archive - a visual link with our past and our heritage - is preserved at the John F. Germany Public Library for the public to view and use.

Today the negatives are preserved in a climate-controlled vault in the John F. Germany Public Library. In addition to duplicating the fragile negatives, the Library has made reference prints for public examination. Burgert Brothers was a commercial photography firm, and fortunately for the area a superb one. They are worthy representatives of the hundreds, possibly thousands of commercial photographers who accurately and often beautifully recorded the American scene. Read more about the Burgerts and their photographic collection at Preserving the Memory of Ybor City, Florida by Cameron B. LeBlanc, Emory University. This is the source of much of the details presented in the collection history above.

Newberry at

TampaPix 1920 Cirkut Camera view of downtown Browse the Burgert Bros. collection at the University of South Florida Search or browse the collection at the THCPLS with thumbnail images from www.lamartin.com

Pioneer Commercial Photography

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Walter

Burgert is perhaps the least remembered brother by the remaining Burgert

descendants and by the local community. He was also probably the least

successful of the boys in terms of using his abilities to establish himself in

the business world, with the exception of his brother Albert who was impeded

by a mental disability.

Walter

Burgert is perhaps the least remembered brother by the remaining Burgert

descendants and by the local community. He was also probably the least

successful of the boys in terms of using his abilities to establish himself in

the business world, with the exception of his brother Albert who was impeded

by a mental disability.

Occasionally they had to construct or adapt special equipment. They

owned an International van that was especially modified to meet their

photographic needs. The truck had special jack levelers so that if the

vehicle stopped on uneven ground the levelers would level it. On the

roof was a platform that could be elevated by crank to the height

necessary to shoot the scene. To protect delicate photography equipment

from bouncing and shifting around over rough roads and quick stops, the

inside of the van had several compartments where the equipment fit

snugly and could be securely fastened down.

Occasionally they had to construct or adapt special equipment. They

owned an International van that was especially modified to meet their

photographic needs. The truck had special jack levelers so that if the

vehicle stopped on uneven ground the levelers would level it. On the

roof was a platform that could be elevated by crank to the height

necessary to shoot the scene. To protect delicate photography equipment

from bouncing and shifting around over rough roads and quick stops, the

inside of the van had several compartments where the equipment fit

snugly and could be securely fastened down.