|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Clara was named for Capt. Barton's sister, Clarissa Harlowe Barton (Foster) born in 1770, the wife of Richard Foster (b. 1770).

Clara Barton, Founder of the American Red Cross, by Barbara Somervill

The Story of My Childhood, by Clara Barton In 1907, when she was 86 years old, Clara Barton wrote about her childhood in "The Story of My Childhood." Clara neglected to mention dates and so it is difficult to pinpoint when many of the events she writes about took place, but there are a few references to her age, and some events that can be dated approximately based on the context of the event. It appears that some events in her book may not be chronological order according to external sources of dates, such as records of births, deaths, marriages, and other historical information. How well could you remember the events of your childhood, and when they occurred, if you were over 80 years old? The information presented in this section of Clara's childhood has been arranged to best fit the clues found in the context of her writing.

Preface to "The Story of My Childhood" Dear Miss Clara Barton: Our classes in The History of the United States are studying about you, and we want to know more. Our teacher says she has seen you. That you live in, or near Washington, District of Columbia, and that, although very busy, she thought you might be willing to receive a short letter from us, and I write to ask you to be so kind as to tell us what you did when you were a little girl like us. All of us want to know. I am almost thirteen. If you could send us a few words, we should all be very happy. I write for all. Your little girl friend,

Mary St. Clare, New York. Yours truly, James C. Hamlin.

Center, Iowa, May 24th, 1906. Dear Children of the school, Faithfully your friend, CLARA BARTON. Glen Echo, Maryland, May twenty-ninth, 1907.

Early Family Life

Clara wrote about her own arrival into the Barton family in "The Story of My Childhood" There can be no doubt that my

advent into the family was at least a novelty, as the last before me was

a beautiful blue-eyed, curly-haired little girl of a dozen summers.* That the event was probably looked for with interest is shadowed in the

fact of preparations made for it.

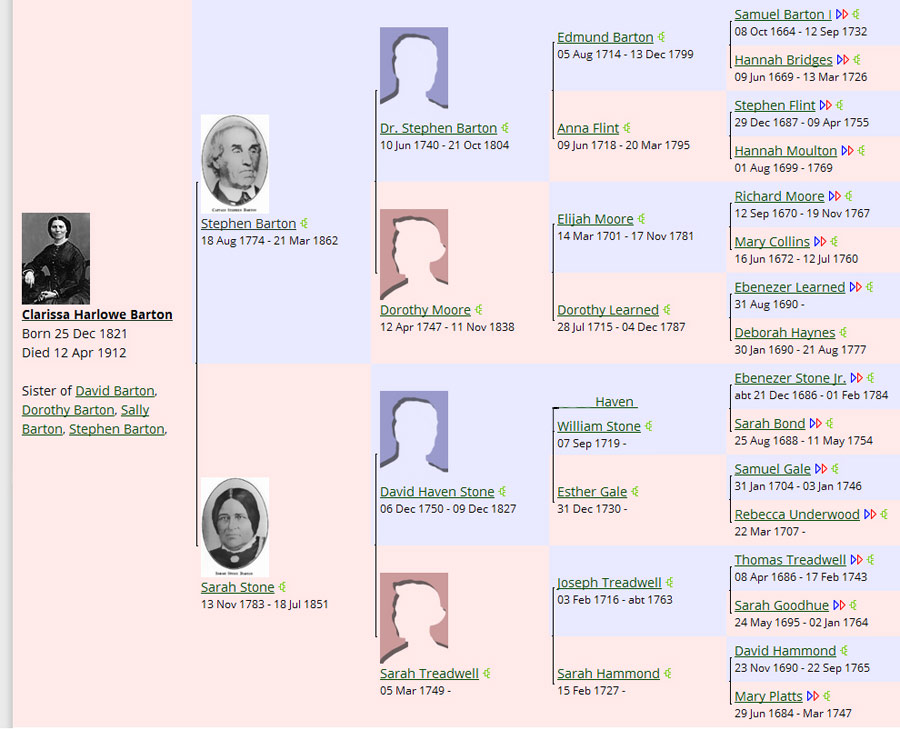

Ancestry

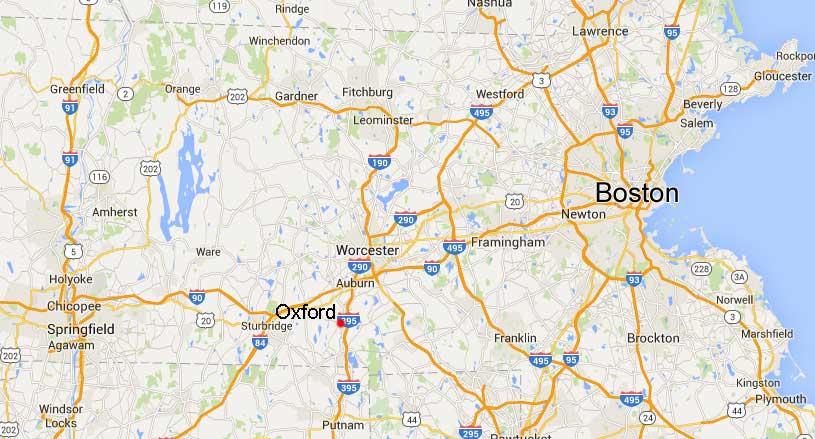

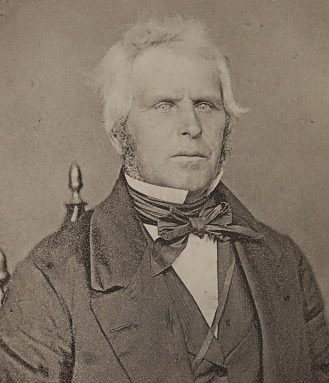

Clara's father, Capt. Stephen Barton (b. 1774), was one of twelve children of Dr. Stephen Barton (b.1740 at Sutton, Mass.) and Dorothy Moore (dau. of Elijah Moore and Dorothy Learned). Dr. Stephen was a trader in the mid 1760s, then landlord of the town tavern before becoming physician. He was a one of four children of Edmond Barton (b. 1714) and Anna Flynt of Salem. They settled in Sutton (Millbury). Edmond was a soldier of the French War. He was one of 8 children of Samuel Barton of Framingham, Mass. and Hannah Bridges (prob. dau of Edmund Bridges, Jr. of Salem.) The first record of Samuel was as a witness at a Salem witch trial. He was later warned against settlement at Watertown in June 1693. In 1716 Samuel bought the Elliott grist mill in Oxford. He died in 1732, leaving all his lands and moveable estate to his son Caleb. History of the Town of Oxford, Mass, With Genealogies & Notes on Persons & Estates,1892

Sarah Stone was the daughter

of David Haven Stone and Sara Treadwell.

David was originally surnamed Haven, but he adopted his step-father

William's name of Stone. In his

marriage intention of June 8, 1776, he is called David Haven, but in the

marriage record of July 25,1776, he is called David Stone.

Find a Grave

History of the Town of Oxford with Genealogies Clara Barton Ancestry Tree

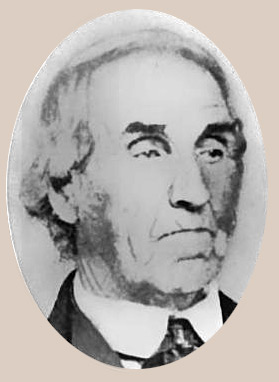

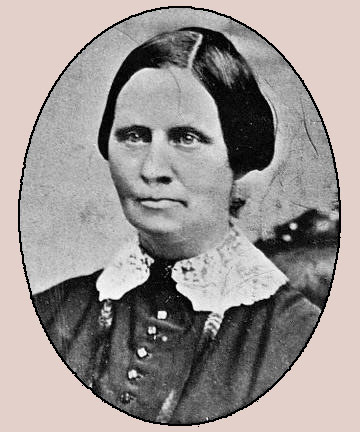

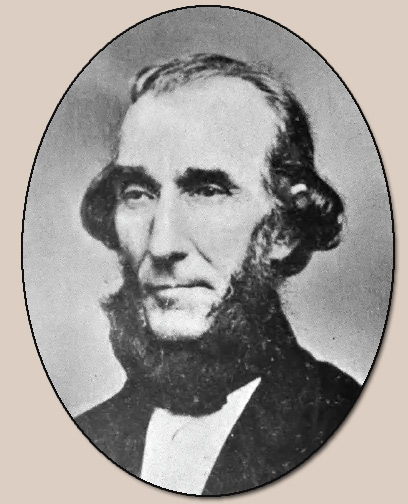

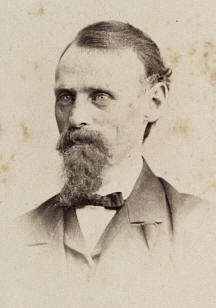

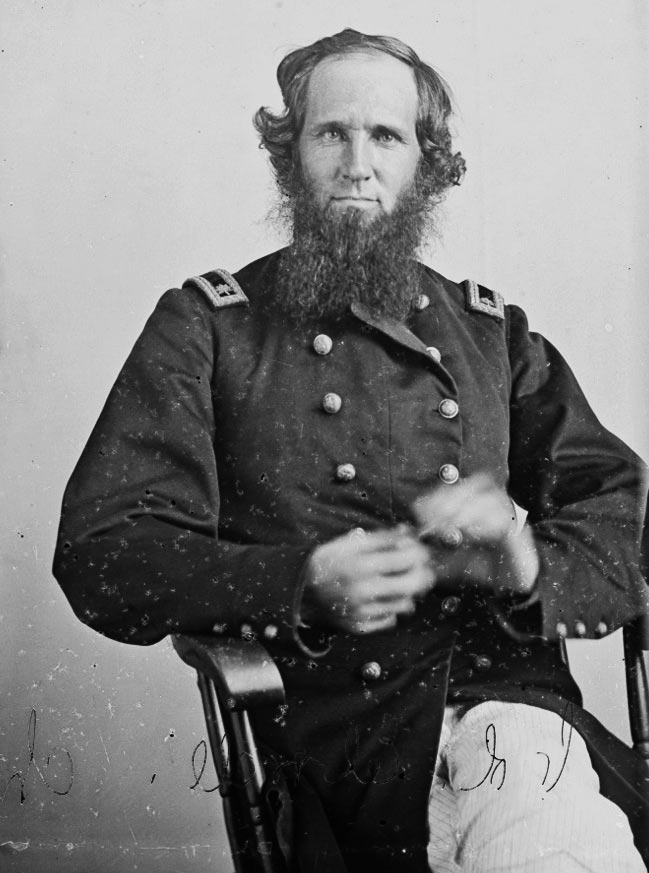

Clara's father, Capt. Stephen Barton

**If Stephen Barton enlisted when he was 21, it would have been in 1795, the year the treaty of Greenville was signed to end the war. Serving for 3 years under Gen. Wayne would have been impossible since Wayne died in 1796 at age 51. He may have enlisted when he was younger than 21. The Northwest Indian War (1785–1795), also known as Little Turtle's War and by other names, was a war between the United States and a confederation of numerous Native tribes, with minor support from the British, for control of the Northwest Territory (which is now our northern Midwest states). Capt. Barton was a man of much force of character, strong physique, a clear head, quick wit, with integrity and manly firmness which rendered him a leader among his fellow-citizens, and in politics, was a Democrat. As a soldier, he didn't attain the rank of captain but he preferred using the title and everyone who knew him accepted it. He was socially aware, charitable, had kindly disposition, and was a believer in abolitionism and the importance of education. Capt. Barton was often in town office, a selectman, representative and moderator. He was a warm patriot and at the beginning of the Civil War declared his belief that Lincoln should have called for 200,000 instead of 75,000 men. He was a Royal Arch Mason and was buried with the honors of the order. He died age 87, March 21, 1862.

History of the Town of Oxford,

Massachusetts: With Genealogies and Notes on Persons and Estates,

1892

Clara's

father provided a generous income for the family, owning their farm, a

sawmill and a grist mill.

He was a lover of horses,

and one of the first in the vicinity to introduce blooded stock. He had large

lands, for New England. He raised his own colts; and Highlanders, Virginians

and Morgans pranced the fields in idle contempt of the solid old farm horses.

Clara's mother, Sarah Stone Barton

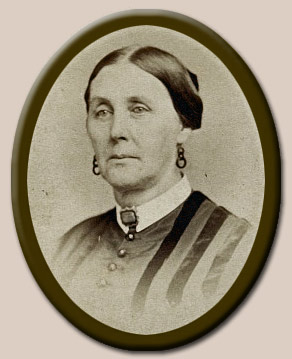

Clara idolized her father but had different feelings for her mother. Clara's mother, while in agreement with her husband on abolitionism, was outspoken on women's rights, eccentric, thrifty, and possessed a fiery temperament and a strong will. She married at 17 years old. She was plain and stern. Sarah usually rose before dawn to begin her chores and ran a tight, efficient home with her daughters sharing in the baking, cooking, sewing, and cleaning. Quick-tempered and sharp-tongued, she frequently scolded her children when they had done wrong.

With Clara's parents frequently at odds with one another, the sometimes stormy couple created a volatile home for their three daughters and two sons. As a result of growing up as the youngest child in an uncertain environment, Clara was timid and withdrawn. Clara was very sensitive, and being scolded hurt her deeply. Throughout her life she would always seek acceptance and confirmation of her worth. The Biography of Clara Barton "The True Heroine of the Age" Life stories of Civil War Heroes Heritage Education: Medical Angels - Clara Barton and the Red Cross

The Life of Clara Barton, Founder of the American Red Cross by W. E. Barton

Childhood and Early Education

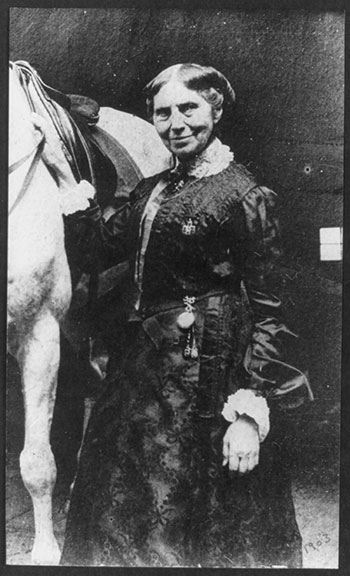

Clara on learning to ride horses:

During the Civil War, the Franco-Prussian War, and the Spanish American War, her skill as a horseback rider was of great service to her. On several occasions, she had to "ride for her life." In reflecting back on this accomplishment, she would say, "When I was a little girl, I could ride like a Mexican." Clara Barton: A Centenary Tribute to the World's Greatest Humanitarian by Charles Sumner Young

Capt. Barton's contribution to Clara's education

**Clara's father participated in the Northwest Indian War of 1785 to 1795 not the French and Indian War, which took place from 1754 to 1763.

One day, Dolly suspected that Clara's ideas of the nation's political and military leaders were somewhat vague, so she managed to get Clara to reveal what her impressions were in regard to the persons whose names she and importance she learned. To the amusement of the family, it was found that she had no concept of their being men like other men, but had invested them with miraculous size and importance.

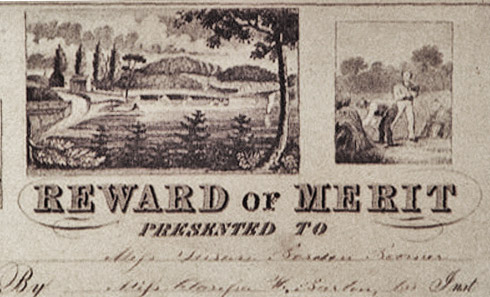

Clara's early formal education When she was three years old (not an uncommon age to start a formal education at the time) Clara was sent to school with her brother Stephen, who carried her nearly a mile through the snow drifts on his shoulders. Among her childhood teachers was Col. Richard Stone.

**No known connection has been made or implied between Clara's teacher, Col Richard C. Stone (b. July, 1798, R.I.), and Clara's maternal grandfather's adopted family, the stepfather of David Haven Stone; William Stone and his father, Ebenezer Stone, Jr. Richard C. Stone was a descendant of Hugh Stone of Warwick, R.I., 1659. Richard's grandfather was Samuel Stone of Cranston, son of Rufus Stone and Sarah Lewis.

When, after a

few weeks, Clara's brother Stephen was declared by the committee to be too

advanced for a common school, and was placed in charge of an important

school himself, Clara's unique transportation became the responsibility of

her other brother,

David. No colts now, only solid wading through the high New England

snow drifts. Serious illness - age five Clara had no recollection herself, but in later years she was told that when she was five years old, she became so seriously ill that the doctor was summoned from a nearby town by a rider who rode out on his fastest, strongest horse, with such haste, that those who saw him knew something bad had happened at the Barton's. When he returned with the doctor, people of the town had gathered in the yard and along the road.

Clara wrote about her first recollection of the

event--her recovery:

Clara shows advanced learning abilities, but excessive shyness Early on, Clara's teachers were impressed with the quiet girl's advanced reading abilities, and soon were also pleased with her accomplishments in writing, arithmetic, and geography, but her shyness hindered her ability to make many friends or have playmates. At school, the only known friend Clara Barton had as a child was Nancy Fitts.

Years of change - ages six through eight

For the next few years, Clara indulged

herself by writing verses. Colonel Stone had closed his series of common

schools, and opened a special institution on Oxford Plain, known as the

"Oxford High School." Its fame had spread for miles around, and it was

regarded as the "Ultima

Thule" for teachers, and in a manner a stepping stone or opening

door to Harvard and Yale.

These were years of change in the Barton family. Her brothers had become of age and were young men of strength, character and enterprise. They had bought their father's two large farms and commenced business in earnest for themselves. Their father had purchased another farm of some three hundred acres, a few miles nearer the center of the town. It was a place of note, having been one of the points used for security against the Indians by the old Huguenot Settlers of Oxford, and which has made the town historic. Their main defense was on "Fort Hill," several miles to the east.

Clara was naturally greatly

interested in the changes, and gave them all the time she could spare from

her increasing studies.

Clara starts high school

Due to her advanced academic capability for her age, when Clara was eight years old, her parents tried to help cure her of her shyness by sending her to Col. Richard Stone's high school in Oxford, but their strategy failed. Clara became more timid and depressed and would not eat. She was immediately removed from the school and brought back home to regain her health.

I can recollect even now that my life seemed very full for a little girl of eight years. During the preceding winter I began to hear talk of my going away to school, and it was decided that I be sent to Col. Stone's High school, to board in his family and go home occasionally. This arrangement, I learned in later years, had a double object. I was what is known as a bashful child, timid in the presence of other persons, a condition of things found impossible to correct at home. In the hope of overcoming this undesirable mauvaise honte, it was decided to throw me among strangers.

Clara recalls the events of starting high school It was a cold and bare April when Clara's father took her to the school in his carriage; she brought with her a small dressing case which she dignified by calling it a "trunk," something she never had. Col. Stone's house adjoined the school, and both seemed enormously large to Clara.

Clara's health deteriorates due to anxiety and lack of food Clara admits that her shyness was her greatest problem in her childhood, resulting in a great fear of public speaking, and that it was with her all her life:

More about Richard C. Stone

and his school, from Click the image at right.

Clara's second home

Around 1830, when Clara was around 9, her family relocated to help a family member, Susannah Learned, as her husband Captain Jeremiah Learned had died in 1829 and left her with four children and a farm. The house that the Barton family was to live in needed painting and repair. Clara was persistent in offering her assistance, for which the painter was very grateful. After the work was done, Clara felt at a loss because she had nothing else to do to help and not feel like a burden to her family.

Clara's memories of her second home, from "The Story of My Childhood" by Clara Barton:

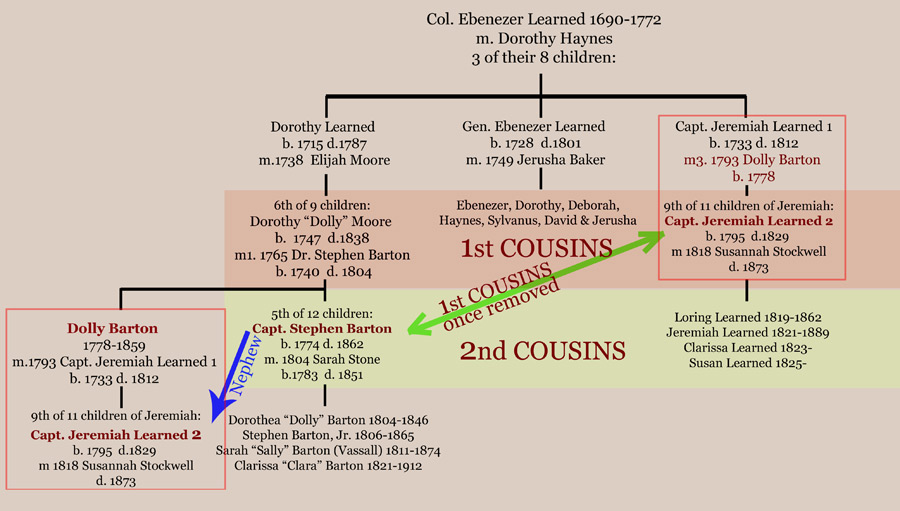

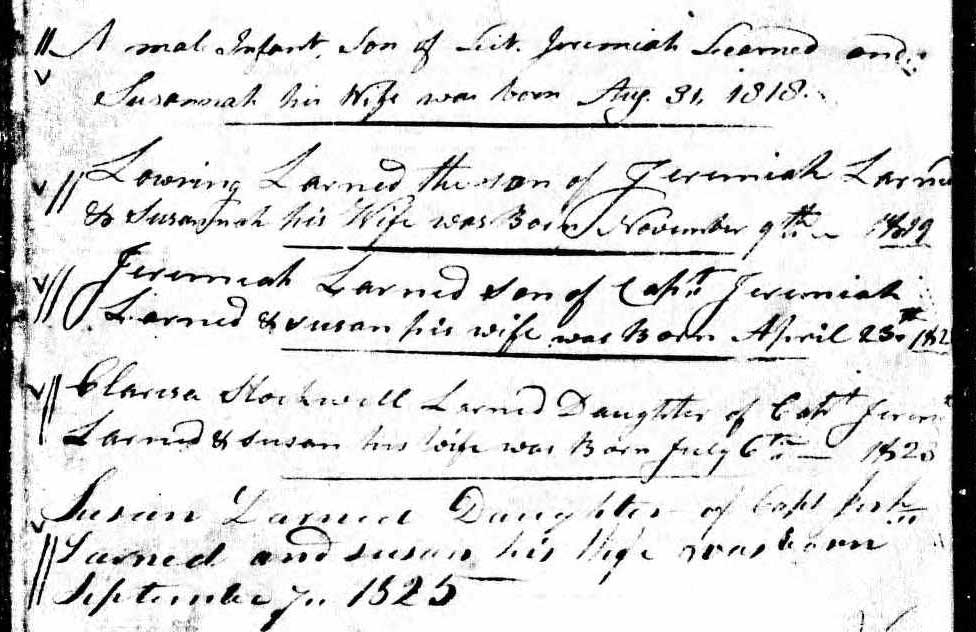

**The Jeremiah Learned whom Clara refers to actually had two relationships to Clara's father. On the Barton side, Capt. Jeremiah Learned (2) was a son of Dolly Barton Learned, Capt. Stephen Barton's sister. So Capt. Jeremiah Learned (2) was Capt. Stephen Barton's nephew. But Capt. Jeremiah Learned (2) and Capt. Stephen Barton were also 1st cousins, once removed, on their Learned side of the family. Jeremiah's father, Capt. Jeremiah Learned (1), was married four times. Jeremiah (2) was his son from his 3rd marriage. After his 2nd wife died, Jeremiah (1) married in 1793 to Dolly Barton, his sister's granddaughter (the daughter of Dr. Stephen Barton and Dorothy Moore Barton.) Dolly was 55 years younger than her husband Jeremiah Learned (1). When they married in 1793, Jeremiah Learned (1) was 60, his wife Dolly was 15. Dolly had a twin sister named Polly. Dolly died in 1799 and Jeremiah Learned (1) married one more time. See chart below. Jeremiah Learned, History of the Town of Oxford, etc. Barton Genealogies, History of the Town of Oxford, etc.

The two Learned hill farms were

sold to Clara's brothers who entered into a partnership as the well-known

firm of S & D Barton, a firm they mainly continued in throughout their

lives. Thus, Clara became the occupant of two homes; her sisters

remained with their brothers, none of whom were married. Clara takes an interest in helping to renovate the house Clara's removal to the second home was a great novelty to her. She became observant of all changes made. One of the first things found necessary on entering a house of such ancient date, was a rather extensive renovation, even for those days, of painting and papering. The leading artisan in that line in the town was Mr. Silvanus Harris, a courteous man of fine manners, good scholarly acquirements, and who, for nearly half a lifetime, filled the office of town clerk. The records of Oxford bear his name and his beautiful handwriting as long as its records exist. Clara recalled:

Clara learned how to hold her brushes, and how to take care of them. She was allowed to help grind paints, shown how to mix and blend them, how to make putty and use it, to prepare oils and dryings, and learned from experience that boiling oil was a great deal hotter than boiling water. She was taught to trim paper neatly, to match and help to hang it, to make the most approved paste.

Clara's male cousins were surprised that she was good at keeping up with such tasks as horseback riding. It was not until her late childhood after she had injured herself that Clara's mother began to question her playing with the boys and began to steer her towards more girlish activities, so she invited one of Clara's female cousins over to help develop her femininity. Upon learning from her cousin, she gained proper social skills as well. To gain her parents' acceptance, Clara began to take on traditionally feminine household tasks, embracing the strong work ethic they instilled within her.

Commissioned painting by Rose Colligan from Deviant Art website

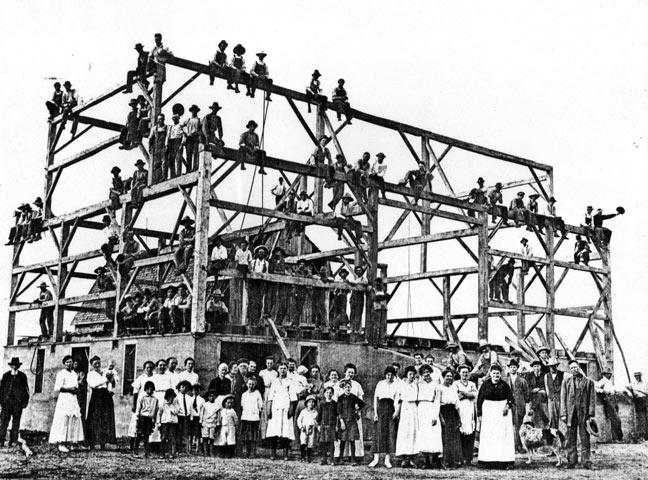

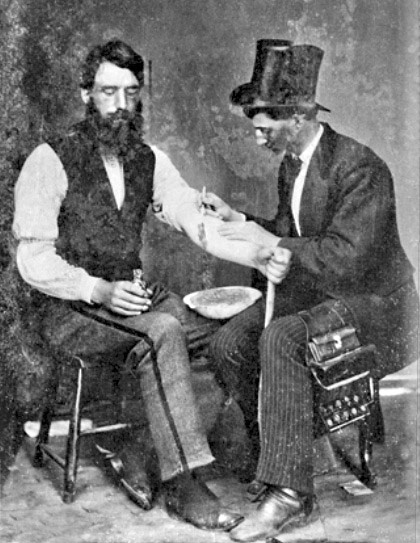

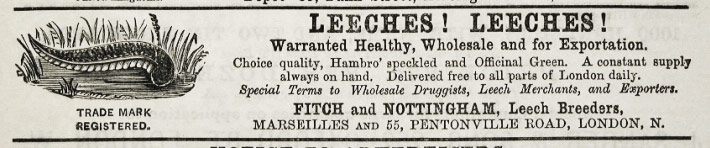

Clara's first nursing patient, her brother David In the summer of 1832, when Clara was 10, her brother David fell from the rafters at a barn-raising and soon developed complications. Clara took it upon herself to nurse him back to health. She learned how to give him the prescribed medication as well as how to place leeches on his body to bleed him. (This was a regular treatment during this time.) Clara continued to care for David with great devotion for two years. He eventually made a full recovery.

A "Steam Doctor" cures David Barton

It was at this time that a disciple of Thomsonianism, a "Steam Doctor," named Dr. Asa McCullum resided in a neighboring town and had followed David's remarkable case with interest and pity and was convinced that the right remedies had not reached been tried.

"Thomsonian Medicine" or Thomsonianism was an alternative system of medicine developed by Samuel Thomson, a self-taught American herbalist and botanist, whose system enjoyed wide popularity in the United States during the 1800s. In the first half of the 19th century his system had numerous followers, including some of his sons. Thomsoniansm was based upon opening the paths of elimination so that toxins could be removed via physiological processes. There were also many skeptics who called it quackery.

David's cure leaves a void in Clara's life Now that David was cured, Clara once again felt free. Life seemed strangely idle to her. She wondered that her father took her riding so often, and that her mother hoped she could make her some new clothes, because in the two years past she had not grown an inch, had been to school only half a day, and only gained one pound.

This period of Clara's young life had longer term effects. In some ways it served to heighten serious defects in her personality. The seclusion caused her bashfulness to increase. She grew even more timid; shrinking and sensitive in the presence of others. She wrote:

As usual, her sister, Sally, came to her rescue. She took advantage of Clara's all-absorbing love of poetry and made a weapon of it by providing Clara with poetical works of Walter Scott, whom she previously had not read, and proposed that they read them together.

The ice skating accident Directly in front of Clara's home was a small, circular, natural pond, fed by springs in the bottom and surrounded by hills forming a basin in which the little pond during the winter "becomes a thing of beauty and a joy forever to the skater." From its sheltered position it froze smooth and even and had no danger spots. The little pond was Clara's early love; the home of her beautiful flock of graceful ducks.

Her brothers were all fine skaters, and Clara wanted to skate, too, but skating had not then become customary, in fact, not even allowable for girls; and when, one day, her father saw her sitting on the ice attempting to put on a pair of skates, he seemed shocked, sending her to the house, and saying something about "tomboys." But this did not cure Clara's desire; nor could she understand why it was not as well for her to skate as for the boys; she was as strong, could run as fast and ride better, indeed they would not have presumed to approach her with a horse. Neither could the boys understand it, and this misconception led them into an error and got Clara into trouble.

Clara's desire to take dancing lessons

Clara recalled another disappointment that was also indicative of the times. During the following winter, when Clara was around 12 years old, a dancing school was opened in the hall of the one hotel on Oxford Plain, some three miles from their home. It was taught by a personal friend of her father, a polished gentleman, resident of a neighboring town, and teacher of English schools. By some chance Clara got a glimpse of the dancing school at the opening, and was seized with a most intense desire to go and learn to dance.

The ox trauma With so much land, and three large barns, there was plenty of cattle on the Barton's farm. A small herd of 25 milk cows came faithfully home at the end of each day, for their milking and their extra supper which they knew awaited them. With the customary greed that accompanies childhood, Clara laid claim to three or four of the handsomest and tamest of the herd, and believed herself to be their real owner. Every evening, Clara went faithfully to the yards to receive them and look after them, with her little milk pail in hand, and became proficient in the art of milking them.

Clara recalls the time she accidentally witnessed the slaughter of one of the farm's oxen:

Circa 1836, Clara in her early teens Great changes had taken place during the two or three preceding years. Her energetic brothers had outgrown farming, sold their two farms on the hill, and come down and bought from their father all his water power on the French River, as well as all obtainable timber land in the vicinity. Sally had married Vester Vassall in 1834 and settled in her home nearby, and Stephen Jr. had married Elizabeth Rich the year before. Mrs. Learned, the widow to whose assistance Clara's father had gone to in her early desolation, had found her children now so well grown as to make it advisable to move to one of the factory villages, where she became a popular boarding house keeper, and her children operatives in the mill. Clara wrote of these times,

Clara's memories of the mills:

Clara's education continues, at home The Barton home was located midway between the two district schools, but a good mile or so from either one. The experiment of sending Clara to school was not repeated, and accordingly, she continued to receive her education at home. Her mathematical brother, Stephen, took charge of that department, and her sister Sally, the other needed studies, while her former patient, brother David, the equestrian teacher of her early youth, continued his practical teaching.

Clara on her brother David's teaching:

Clara returns to public school Finally, a school opened in the north of Oxford that Clara could attend. It was undertaken by Mr. Lucian Burleigh, a younger member of the noted Burleigh family, and brother of William H. Burleigh, the poet. It seemed very strange to Clara to be in school again; she had so long been accustomed to governing herself that she wondered how anyone should need others to govern them. Clara had no doubt that her teacher sensed this in her, and that she seemed equally unaccountable and prudish to him, and so he treated her with the greatest consideration and kindness; advising such changes and additions as seemed suitable, and most in accord with the studies she had taken with her. The school even formed some new classes in branches outside of the customary routine of the public school; as elementary astronomy, ancient history, and the "Science of Language."

After a busy summer another stroke of good fortune came to Clara during the next winter term of school. Mr. Jonathan Dana, one of Oxford's most scholarly men and a teacher of note, commenced the winter school to the south of the Bartons. Clara considered his instruction invaluable as well as the pains he took with her as his eager pupil.

Clara's family was gratified

by her progress and deportment as a student, but still she was different,

timid, non-committal, afraid of giving trouble, and difficult to

understand. Her physical growth had not met their expectations nor

their hopes. She grew slowly and was still a "little girl" in appearance.

This went to show how positive the early check had been, and how slowly

the repairs were made, for it was said in later years that she gained an

inch in height between the ages of twenty and twenty-one.

Early Adulthood - Clara's first job In 1838, Clara wanted to work at her brother's satinet mill in town, but her parents objected. Her brother Stephen stepped forward to speak in her behalf and provided her first employment in his cloth factory as a bookkeeper and clerk when she was sixteen years old.

Satinet is a finely woven fabric with a finish resembling satin, but made partly or wholly from cotton or synthetic fiber. The process developed in Mesopotamia around 5000 BC.

Clara on the subject of getting her first job:

As Clara grew into adolescence, her parents encouraged her involvement in charitable work such as tutoring children and nursing poor families during a small pox epidemic. Unlike most persons her age, Clara chose to spend most of her free time actively assisting others by alleviating their illnesses or troubles. This was the beginning of a lifetime of work from which she would always receive her greatest satisfaction. Clara Barton, founder of the American Red Cross

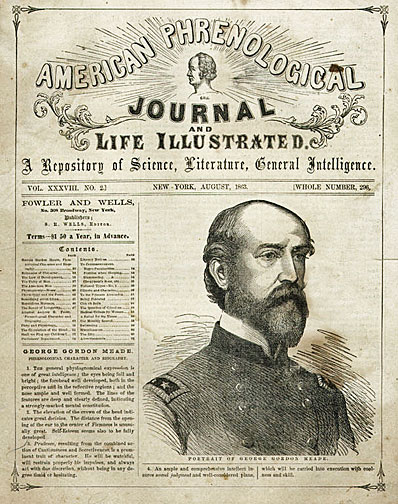

Noted Phrenologist L. N. Fowler advises a teaching career for Clara When Clara was sixteen years old, the famous Fowler brothers (Lorenzo and Orson) visited Oxford. The Fowler brothers were phrenologists--"scientists" who studied the bumps on a person's head to determine their future. After studying her, Lorenzo Fowler declared that a career in teaching would cure Clara of her painful shyness. Clara Barton Birthplace Museum

Clara Barton the school teacher In May of 1839, Clara passed examinations and began a teaching career at the age of 18, teaching at District School Number 9 in rural Massachusetts. Bordentown Historical Society

Clara on passing the exams and her first day of school as a teacher:

Clara Barton and the wedding of her brother, David, Sept. 30, 1839 One early September, Clara's brother David, who was one of the active, popular businessmen of the town, invited her to accompany him to Maine to be present at his wedding and return home with them. Clara wrote:

Clara's teaching career The 1840s found Clara embarking upon her first crusade to aid the distressed and underprivileged. She worked for 12 years as a school teacher at various schools in the area, often working without wages in poorer areas. In 1845 she established a school for the children of her brother’s mill workers.

At one school, having taught classes in a dilapidated building and finding the textbooks and supplies inadequate and the attendance inconsistent, Clara carefully drafted a plan for improvements and presented her ideas at the town meeting. Clara's efforts were rewarded when the school was reestablished in one of the area's largest central mills, equipped with maps, blackboards, and a clock for teaching purposes, per her specifications. Consequently, her 70 pupils—ages four through 24, comprised of American-born, as well as English, Irish, and French-born students—were able to attend her class regularly and receive a better education in reading, writing, and arithmetic, algebra, bookkeeping, philosophy, chemistry, and ancient and natural history.

Clara's students regarded her with respect and admiration, and her innate shyness seemed to dissipate before her attentive, appreciative audience. Her own interest in learning was infectious; her treatment of her students was judicious and fair, and she had a talent for being a disciplinarian without needing to use force. However, as much as she cared about her students and the classrooms in which she taught, the unique challenges of each school held her interest, and once overcome, she pursued new challenges elsewhere. On

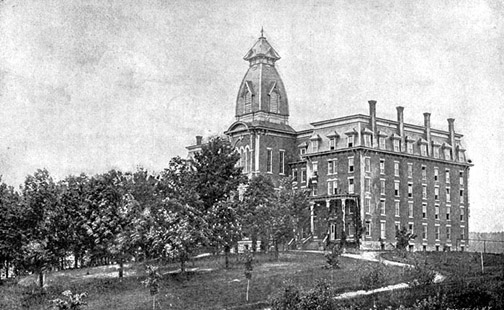

April 19, 1846, Clara's sister Dorothea (Dolly) Barton, died. Higher Education In 1849, Clara contemplated the years ahead and dreaded to think of the limitations for a woman of the time living in a milling and farming community. She needed challenges beyond teaching in a small town, and decided to further her education so she could advance her career. With few schools offering a higher education to women, in 1850 at age 29, she enrolled out of state at Clinton Liberal Institute, a well-respected, co-educational academy in Clinton, New York, run by the Universalist Church (the denomination of the church in which she had been raised). It was here that she made several new friends from all over including Mary Norton of Hightstown New Jersey. Being 10 years older than the average female student at the academy, she did not easily find friends among her peers, but her dedication to her studies in language and writing skills occupied most of her time. An even greater difficulty to overcome was dealing with her separation from home and family. For though she was adventurous and ambitious, deep inside she was still the timid girl of her childhood.

Clara leaves Clinton, establishes free public school

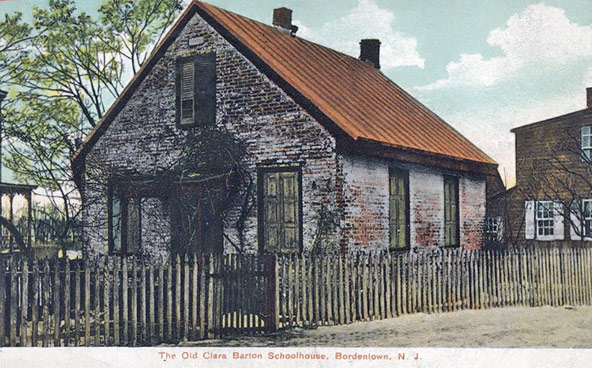

In July 1851 when her mother passed away, Clara was overwhelmed by a feeling of helplessness. With the death and financial difficulties weighing heavily upon her, Clara left Clinton regretfully, her education incomplete and her career and future uncertain. In October of 1851, Clara travelled to Hightstown, New Jersey to visit Mary Norton, a school friend from her time at Clinton, and resumed her teaching career by teaching at local schools in the area. There, she was bored and restless, and lacked privacy in the Norton household. A social visit to Bordentown made an impression on Clara; looking around the streets she saw ... “idle boys. But the boys! I found them on all sides of me. Every street corner had little knots of them, idle, listless, as if to say what shall one do when they have nothing to do?” Clara immediately sought out the chairman of the school committee and asked for an interview. Laws existed in New Jersey for free public education but were never implemented. There were plenty of private schools and pauper schools but neither alternative offered an opportunity for most of the children of the community. Clara was given a ramshackle one room school house. On the first day six children showed up for school. They spent the first few days cleaning up the school house and getting it ready for children. By 1853 there were over 600 children in the program, receiving lessons from teachers housed in locations all over the city. Fanny Childs, a friend from Oxford, came to assist Clara with the teaching. The people of Bordentown were so impressed with their new free school that they spent $4,000 to build a new and much larger brick building with 8 classrooms to accommodate 600 students. When Schoolhouse Number One opened in the fall of 1853, enrollment grew rapidly under her leadership and attendance grew to 603. Clara was stunned to learn that the school board decided that a school with so many students was beyond the administrative capability of a woman, let alone one this young. Instead of hiring Barton to to be headmaster, the board hired J. Kirby Burnham and paid him twice as much ($500) as they were paying Clara. Clara was demoted to "female assistant" with disastrous results. The teaching staff became widely divided, quarrels ensued over instructional methods, and Clara's health began to deteriorate. She grew weak and lost her voice. By February of 1954, Clara and Fanny Childs had both resigned and the Bordentown free school was in disarray. Burnham himself was dismissed at the end of the school year, and finger-pointing by the local newspaper and townspeople added to the contention.

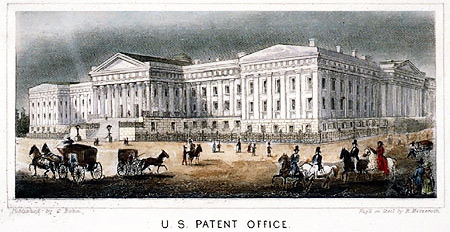

Clara goes to Washington D.C. and is hired at the U.S. Patent Office

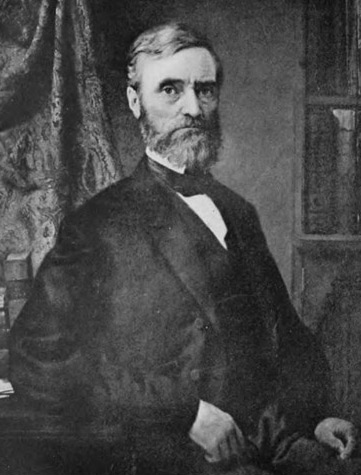

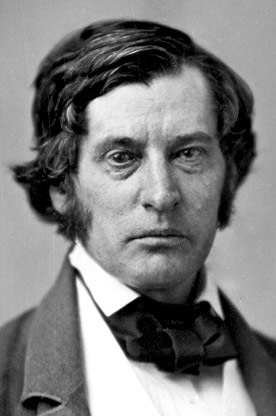

In 1854, Clara and Fanny Childs decided to journey to the nation's Capital in search of new employment opportunities. Once settled in Washington and becoming familiar with the town and how to get around, Clara sought out Alexander DeWitt, the congressman from her district in Massachusetts. DeWitt opened doors for Clara, to both the political and social worlds. Among those he introduced her to was Charles Mason, Commissioner of the Patent Office. DeWitt remained supportive of Clara as long as he was in Congress, but it was Mason who emerged as her patron. DeWitt suggested to Mason that Clara would make a valuable worker in the Patent Office. Mason was impressed with her skills as a conversationalist, fair judgment, and political awareness. He offered her the coveted job of a recording clerk-copyist where she began working in July 1854, copying patent applications, caveats, and regulations at a rate of 10 cents per 100 words copied.

Clara grew remarkably skillful at this and from it she learned a great deal about the state of developing technology in a variety of fields. In this respect, the job was part of her continuing education, something that she actively pursued all her life. To boot, she earned an average of about 80 dollars a month, enough for her to live in modest comfort. Her carefully scripted writing style and the rigorous honesty displayed in her work soon made Clara virtually indispensable to Mason. Mason was a relentless foe of corruption, whether it was the matter of a clerk-copyist selling patent information or simple carelessness due to lack of moderation or restraint. Mason relied on Clara in confidential matters that came before him, and she gave him her undivided loyalty. Clara's typical work day

Clara's day started as early as 4am. After a scripture reading and prayer of thanksgiving, she dressed and then studied French. French recitation followed breakfast and then a walk of a mile to the Patent Office. She arrived at 9am and worked until 3:30pm. When allowed, she would take work home. After dinner the copying was taken up again, sometimes in the company of Samuel Ramsay, her good friend from Clinton days who was in Washington to write a history of Virginia.

Women in the U.S Government workforce Barton's position and that of several other female copyists at the Patent Office was not a standard arrangement. The Federal bureaucracy, though small in size, was still a man's world. Mason was one of the few superintendents who was willing to hire women, even sparingly. He believed women usually made very good copyists and were more industrious than most of the male copyists. He tried to protect Clara's job for the years she worked there by not publishing her name in the official roll.

Mason's chief, Robert McClelland, Secretary of Interior, was of a different opinion. By pressuring Mason to dismiss his female workers, Barton's position was always at risk. McClelland deemed it unacceptable for men and women to work side by side. He wrote DeWitt: "there is such and obvious impropriety in the mixing of the sexes within the walls of a public office that I am determined to arrest the process." In Barton's behalf, Mason resisted the attempt to deny him his most trusted subordinate. As the controversy built up, Mason, for personal reasons, resigned his office only to resume it several months later. Clara receives equal pay but sexual harassment in the workplace Clara's prospects improved immediately upon Mason's return and for the next year and a half she was paid at an annual rate of $1,400. By the standards of the day, this was a goodly sum, Mason's salary being only $3,000. Mason once again took up the war on the corrupt issuing of patents, and Clara, working with him, developed a nose for "rotten eggs in the basket." But the consequences of her return to favor was considerable sexual harassment and she became the target of cat calls and tobacco juice. Clara was working in a masculine domain, where she believed she had every right to be, and it would take more than dirty looks and bad language to dislodge her. She was more efficient than any of her male competition; Clara knew it and so did the men. So long as Judge Mason was conducting the business of the Patent Office, she was sure her right to work would be honored. Clara's social and political life in Washington D.C.

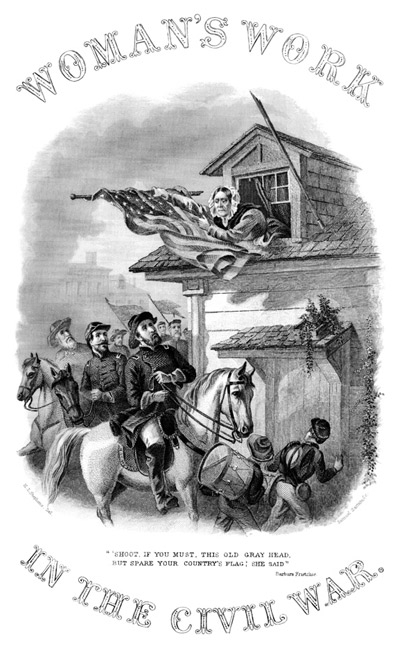

While in Washington D.C., Clara lived in a boarding house with a fellow Patent Office worker, John Fales, and his thin, jolly wife Almira Fales, whose companionship she enjoyed. Almira was a storyteller, a devotee of the jovial manner, gangly, abrupt and disconcerting. She believed strongly in the necessities of charity and pursued her private projects with a drive that would later match Clara's. Almira's enthusiasm and passionate devotion to her northern background would in later years cause her to wholeheartedly embrace relief work during the Civil War--work that was to have a direct effect on Clara's own role in that conflict. But in 1854, Almira was simply an amusing personality in Clara's gallery of friends and acquaintances, providing a nice contrast to the more sophisticated and serious society of Alexander De Witt and the Masons. See the boarding house where Barton lived, now the Missing Soldiers Office museum. More about Almira Fales from Woman's Work in the Civil War: A RECORD OF HEROISM, PATRIOTISM AND PATIENCE BY L. P. BROCKETT, M.D., Author of "History of the Civil War," "Philanthropic Results of the War," "Our Great Captains," "Life of Abraham Lincoln," "The Camp, The Battle Field, and the Hospital," &c., &c. AND MRS. MARY C. VAUGHAN. WITH AN INTRODUCTION, By HENRY W. BELLOWS, D.D., President U. S. Sanitary Commission. ILLUSTRATED WITH SIXTEEN STEEL ENGRAVINGS. ZEIGLER, McCURDY & CO., PHILADELPHIA, PA.; CHICAGO, ILL.; CINCINNATI, OHIO; ST. LOUIS, MO. R. H. CURRAN, 48 WINTER STREET, BOSTON, MASS. 1867.

Winds of change were blowing across the nation in the mid-1850s and Washington was at the center of this increasingly ominous storm. Being the daughter of Sarah Stone Barton, Clara had long deplored the evils of the slave system. With the majority of Americans, Clara was strongly opposed to the extension of slavery in the territories but she was not a fiery abolitionist. The new Republican Party appealed to Clara because of its stand against the spread of slavery westward.

Barton's attraction to politics and public life and her friendship with Congressman DeWitt often took her to the halls of Congress. In 1856 she witnessed Senator Charles Sumner of her own state of Massachusetts deliver his famous "Crime against Kansas" speech, denouncing the "Slavocrats" who were determined to make Kansas a slave state. He drove home his point for Clara. She said in retrospect, "The American Civil War began not at Sumter, but at Sumner."

Buchanan's election to the presidency brought a drastic change in government patronage appointees which had an adverse effect for Clara. Though she was unable to vote, she had made public her support for John C. Fremont, the Republican opponent of Buchanan. At one social gathering her strongly stated views caused one of her friends to plead understanding because, he said, Clara had too many cups of coffee. Fremont was defeated and DeWitt was turned out of office. With Jacob Thompson as Secretary of Interior, Judge Mason's days were numbered. There would be new faces all around the Patent Office, those of deserving Democrats. Barton's government service appeared to be at an end, and before the year was out, she found herself out of a job and heading to North Oxford, to home and family. Read a full text transcript of Charles Sumner's The Crime Against Kansas speech, delivered in the Senate of the Unites States - May 19, 1856.

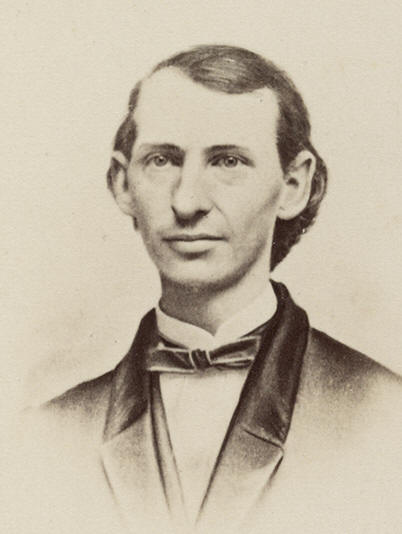

Stephen Barton, Jr., Clara's Brother

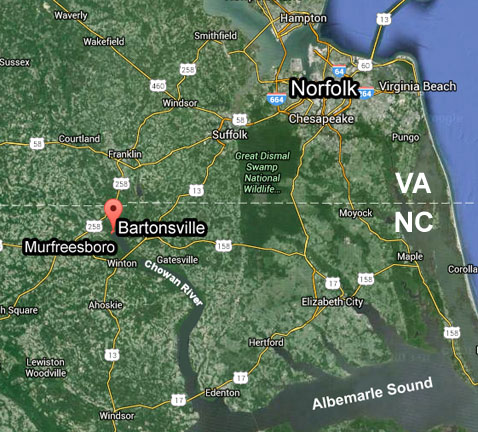

In 1856 Stephen

purchased a tract of timberland and a steam sawmill on the Chowan

River in Hertford County, North Carolina. At this site, about two miles north of the

mouth of Meherrin River, Barton and a crew of New England artisans,

including several members of his family, built another mill town,

Bartonsville. A post office was established there, along with

wharves, lumberyards, a gristmill, warehouses, and other facilities.

In 1860 he acquired North Carolina rights to machinery for making

plow-handles and plowbeams, and he had produced many thousands by

the time the Civil War broke out in the spring of 1861.

Clara's family problems back home

For the next four years Clara was

almost totally occupied by family matters, most of which were very

troublesome. Clara spent

time with friends and family in New York and Massachusetts where she

enrolled in French and art classes. But her dedication to helping others

would never desert her.

Her

brother-in-law, Vester Vassall, appeared unable to provide for her sister

Sally and their two children. This was especially troubling for

Clara because one of the boys, Irving, had long been a favorite. Born

in Oxford in 1840, at

16 he became consumptive. His mother came with him to Washington to

live with Clara for a while, hoping the milder weather would cure him.

When he showed no improvement there, Clara took him to Minnesota at no

small expense to herself, hoping the dry, cold air would help. After

some time there, Irving wrote that he was very unhappy and his health

showed no improvement. His demands for money put considerable stress

on Clara who continued to worry about his condition. But Clara

recognized that he was self-indulgent and that she by her kindness may

have helped make him so. He passed away on April

9, 1865 in Washington.

Vassall family photos courtesy of Library of Congress

Then there was Mattie Poor, a young relative studying music in Boston. Clara had paid some of her expenses, but the girl refused to take a job and continued to badger Clara for money. Worries mounted due to growing anxiety about Clara's father's advanced age and declining health. He had moved in with his son David and his wife, after the death of his own wife, Sarah. When Clara came back to North Oxford, she too stayed with David and her father, and a feeling of resentment on the part of David with his wife Julia became more pronounced the longer Clara stayed with them.

Clara rehired at the U.S. Patent Office Fortunately, it was not long before Clara was recalled to her post at the Patent Office as a copyist in the Fall of 1860, with the election of President Abraham Lincoln. Clara begins volunteer service during Civil War Clara would return to the Patent Office building again during the Civil war, when it functioned as a hospital for wounded soldiers. Her story is entwined with the history of the Patent Office Building—first in its use as a federal facility, later as a Civil War hospital, and today as the art museum that houses her portrait--the National Portrait Gallery. Miss Barton was 40 years of age when she first turned her attention to the great works of humanity which have made her name famous. She might properly be called the Florence Nightingale of America. Like her British prototype, her works of mercy were not confined to her native land, but were carried even into the eastern hemisphere.

The Civil War

On April 12, 1861, the Civil War began with the firing on Ft. Sumter, South Carolina. On April 19, en route to defend the nation’s capital, the 6th Massachusetts Infantry was attacked by mobs of southern-sympathizing Baltimoreans as the soldiers marched across town. They arrived in Washington, DC, beaten and with several members of their regiment dead. Clara found them temporarily quartered in the Senate Chamber of the U.S. Capitol and provided supplies from her own household for their comfort. The overwhelming response to her request for additional supplies for the troops marked the start of her career as the Angel of the Battlefield. Clara exuberantly assisted the Union army by gathering and purchasing provisions for the soldiers, and it wasn't long before local women and relief societies learned of her charitable activities and brought her boxes of goods to deliver to the men.

During the First Battle of Bull Run (First Manassas by the Confederates) in Fairfax County and Prince William County, Virginia in July 1861, the U.S. government—ill-prepared for an escalating war—sent scores of wounded men to the neighboring city of Washington where makeshift hospitals sprung up overnight in homes and unlikely buildings such as the Patent Office. Clara tended to wounded soldiers as they arrived in Washington, DC. and established a distribution agency after receiving additional supplies sent in response to an advertisement in the Worcester Spy.

After aiding the soldiers in Washington, she was inspired by her former landlady Almira Fales to actively administer assistance to the wounded on the battlefields. Clara soon would no longer be working at the Patent Office, but would still receive wages from the government due to her staunch support of the Union army. Stephen Barton, Jr. Clara's Brother

Caught with most of his manufactures in storage at the start of the Civil War, Stephen Barton, Jr. sent his crew north and determined to sit out the war at Bartonsville, NC, in order to protect his investment. Stephen was married to Elizabeth Rich of Charleston, Mass., and by her had three sons, one of whom was Samuel R. Barton, who assisted him in creating the mill town at Bartonsville.

Although Stephen opposed

both slavery and secession, he maintained a neutral position in the

war and local Confederate garrisons, respecting his position, left

him alone. Union gunboat officers operating on the Chowan also

understood Barton's situation and did not annoy him, although they

were sometimes able to deliver to him mail or news from his friends

and relations in the North. In the meantime, his relations,

particularly his sister Clara, plotted scheme after scheme for

bringing him out of North Carolina, only to be blocked by his

determination to maintain his lonely vigil at Bartonsville.

NCPedia

Barton, Stephen, Jr.

Death of Clara's father In late 1861, Clara's father fell ill, so she went home to be by his bedside. On his deathbed, he encouraged Clara Barton to continue her patriotic support for the Union. They talked of the war and of her work with the soldiers in Washington. She wanted to provide for the wounded on the battlefields, but as a woman, she was afraid. Her father alleviated her fears and she later confided, “As a patriot he bade me serve my country with all I had, even my life if need be; as the daughter of an accepted Mason, he bade me seek and comfort the afflicted everywhere, and as a Christian he charged me to honor God and love mankind.” Stephen Barton presented his daughter his gold Masonic emblem, asserting that she was to wear it.

Stephen Barton died on March 21, 1862 at his home in Oxford. After his death, Clara returned to Washington, D.C. and pursued a new direction for her relief work. She obtained travel passes and headed for the battlefields. Emboldened by her father's sentiments, she faced her relief efforts with a new courage. She wore her father's Masonic pin throughout the Civil War and later recalled, “My father gave it to me when I started to the front, and I have no doubt that it protected me on many an occasion.”

Clara Barton A Lifetime of Service, The National Park Service,

Clara Barton National Historic Site Clara Barton in the field of war

Clara was not heartily welcomed by army officials who initially refused her assistance and supplies, believing that she would be more of a hindrance than a helper on the field. In that day and age, society frowned upon an unmarried woman straying out of the home, believing that at best she belonged in an organization of women; certainly not alone among men. Though Governor John Andrew of Massachusetts (who was also commander-in-chief of the Massachusetts forces) supported her cause, Clara had to persist in her efforts to convince the quartermaster that she would be a valuable asset on the front lines. Finally, in Aug 1862, Miss Barton gained official permission from an officer named Rucker to transport supplies to battlefields. When supplies were delayed or suppliers were under orders not to advance for fear they would be captured by the enemy, Barton was there to assist. As she noted, “that was the point I always tried to make, to bridge that chasm, and succor the wounded until the medical aid and supplies should come up.” Despite her lack of formal training as a nurse, her

efficiency and drive had a huge impact: she assisted in surgeries, extracted

bullets, comforted the dying, and helped establish field hospitals. As her

biographer Stephen Oates noted, Barton loved associating with the common

soldiers and considered herself one of them. They, in turn, loved and respected

her. She understood more than most the terrible cost of the war, having

experienced it firsthand. In its aftermath, she turned to helping families find

lost soldiers and relatives. Clara's work at Civil War battle sites On August 2, 1862, Clara delivered her supplies to Fredericksburg, Virginia and, in her first encounter with the field hospital, was appalled by the chaos of untrained ambulances, the lack of clean bandages and fresh water, and the delay in the arrival of government issued supplies.

The Battle of Cedar Mountain (Culpepper), Virginia on August 9, 1862 was the first documented battle at which Clara Barton served in the field. She rushed to Culpepper, arriving on August 13, where wounded soldiers filled the train depot that served as a makeshift relief station. The sight that greeted Clara horrified her. Surgeons in pus and bloodstained coats routinely amputated a countless number of shattered limbs, tossing them in heaps outside the door. The filth of the hospital and conditions in which recuperating men lingered sickened her and touched her with sadness. She and a couple of friends who had accompanied her on this mission prepared food, made bandages, held hands, cleaned the hospital and men, and assisted the surgeons in any way that they could. She spent two days and nights tending the wounded. Not long afterwards, her impartial care for the sufferer would take her to a hospital of Confederate prisoners, where she brought every article of food and clothing she could obtain for the comfort of the sick or wounded.

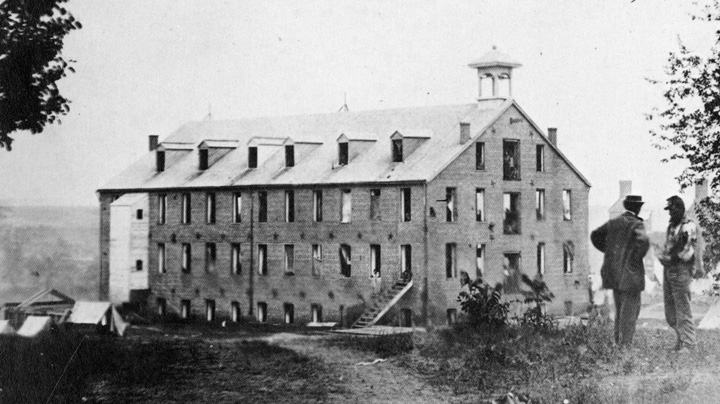

The Second Battle of Manassas (Bull Run), Virginia took place on August 28-30, 1862. The woolen mill just north of town, visited by Clara Barton in 1862, before her service during the Second Manassas campaign.. It was here that she saw her first-ever amputation. From "Mysteries & Conundrums" National Park Service

Battle of Chantilly (Ox Run) After the Second Battle of Bull Run in late August 1862, Clara arrived at Fairfax Station on Sept. 1, tended to the wounded from the Battle of Chantilly, Virginia and prepared the injured for evacuation by train to Washington, DC. Many of these men had received no food or water for two days. Dismayed to see thousands of wounded soldiers blanketing the hillside beneath the blazing sun, Clara immediately prepared them a kettle of cornmeal, and after this was gone created a concoction of what meager provisions were available: crushed army biscuits ("hardtack"), wine, water, and brown sugar. She brought them clean shirts, bound their wounds, gave them their last rites, and offered words of kindness and encouragement to the weary, working without food or rest for two days. Though she endured more than one person's share of work, she discovered that she enjoyed working alone.

Two weeks later on September 14, 1862, at Harpers Ferry and South Mountain, accompanied to the battlefields by two women, Clara found it preferable to do the work herself than delegate orders to others. Antietam (Sharpsburg) On September 17, 1862, Clara was one of few women among the Union and Confederate armies waiting for the bloody Battle of Antietam (Sharpsburg) to begin. She described the experience as

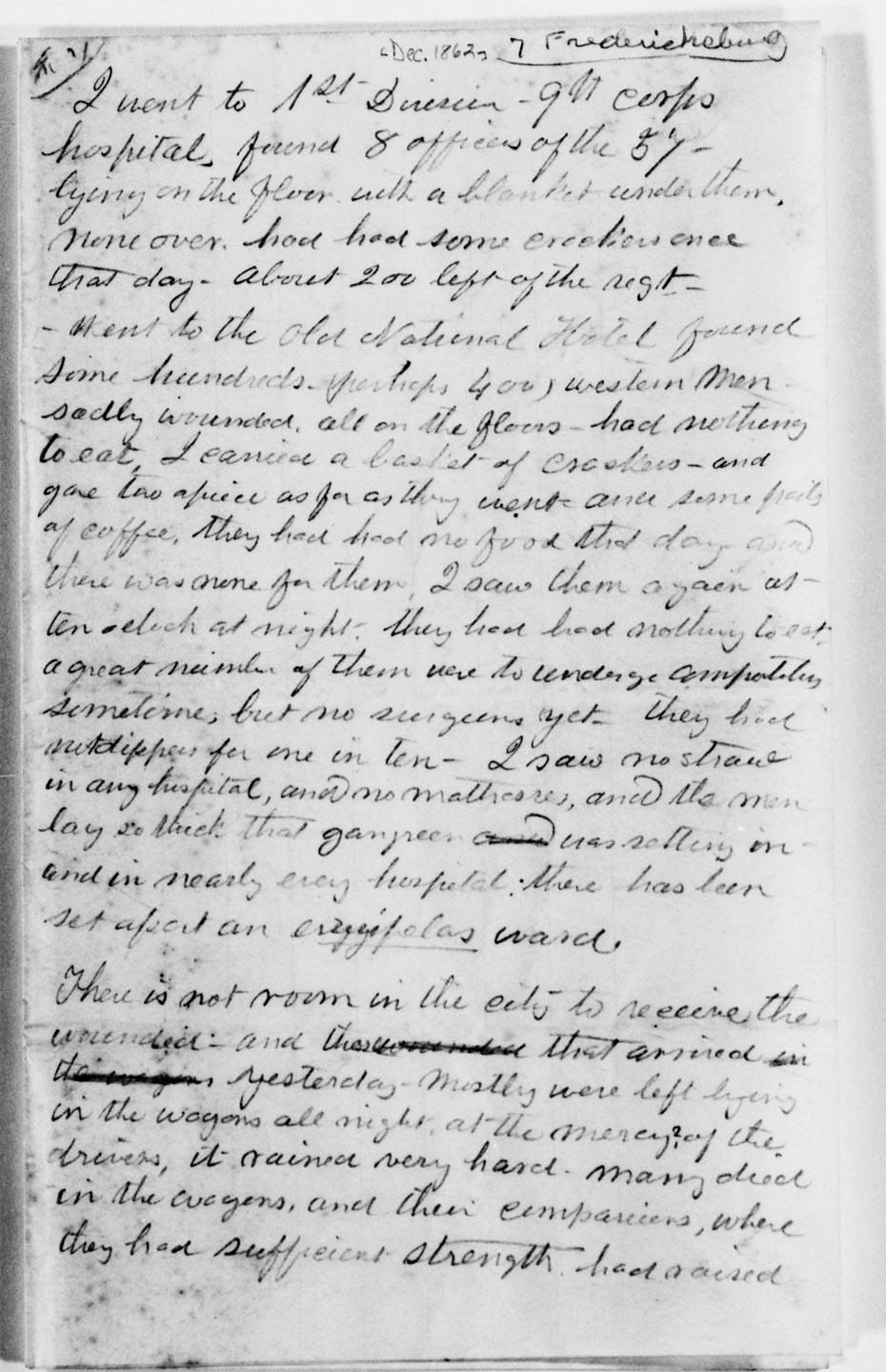

Her presence—and the supplies she brought with her in three army wagons with the Army of the Potomac prior to the battle—was particularly welcome by overworked surgeons who were trying to make bandages out of corn husks. She provided surgeons with desperately needed medical supplies. Clara provided assistance to the surgeons at the Poffenberger Farm (among them Dr. James Dunn whom she had met at Culpeper). By now, having witnessed numerous surgical procedures, Clara no longer flinched at the sight of an amputation that was performed without the use of chloroform on a patient, and neither did she cry when learning of the death of a former class pupil. Although lacking medical training, at the insistence of a wounded soldier, she extracted a bullet from his cheek, using her pocket knife, and while holding the face of another soldier to offer water, had a bullet pass through her sleeve and into the wounded victim. Barton organized able-bodied men to perform first aid, carry water, and prepare food for the wounded. Through all she endured thus far in the war, Clara had become a stronger, confident woman. The appreciation she received from those she nursed gratified her and gave her a feeling of self-worth. Watching her perform her tasks tirelessly, dutifully, compassionately, and without fear, Dr. Dunn's wife remarked that Clara was "the true heroine of the age, the angel of the battlefield." For six weeks Clara ceaselessly toiled in the field, until she was stricken ill with typhoid fever. After a month's recuperation in Washington, she Clara travelled with the Army of the Potomac as it pursued the retreating Confederates into Virginia in Sept. and Nov. of 1862. She caught up with the army at Harpers Ferry and provided aid to the wounded at several minor skirmishes and accompanied patients to hospitals in Washington, DC. Fredericksburg Clara Barton came to Fredericksburg on the eve of a major battle in December 1862 to provide supplies and nursing skills to Union medical staff. She wrote in her journal:

On Dec. 13, 1862, Clara

assisted in a hospital of the IX Corps, which was established at the Lacy

House (Chatham Manor).

Clara tended to wounded soldiers in the temporary hospital established at the Lacy plantation house, and noted in her pocket journal information about the soldiers she encountered, should loved ones want to find the soldiers after the battle. Recording the identities of soldiers in her diaries was a practice she continued throughout the war.

During the brutal battle in mid-December, she and fellow worker Walt Whitman assisted Clarence Cutter (the old regimental surgeon of the 21st Massachusetts) at the hospital set up in the Lacy House. She worked there through the last week in December 1862, living in a tent beside her wagon, and returned to the Capitol only when her supplies were depleted and most of the wounded men had either died or were sent on to Washington for treatment. It would be a long and bitter winter, with no end in sight for the war or its suffering victims. Throughout the war, Barton and her supply wagons traveled with the Union army giving aid to Union casualties and Confederate prisoners. Some of the supplies, like the transportation, were provided by the army quartermaster in Washington, D.C., but most were purchased with donations solicited by Barton or by her own funds. (After the war she was reimbursed by Congress for her expenses.) The intensity of her work in the field gave Clara

little time to dwell on any personal feelings of sorrow, but likewise there was

also little which brought her personal happiness, aside from the appreciation of

thousands of soldiers and their loved ones. The summer of 1863 would change her

fortune. Charleston, Hilton Head, and Morris Island, SC - Clara befriends Gen. John J. Elwell

In 1863, Clara traveled to the Union controlled coastal regions around Charleston, South Carolina. She arrived at Hilton Head in April of 1863 in preparation for the anticipated bombardment of Charleston. There in Hilton Head, she was pleased to be reunited with her brother David who had just been appointed quartermaster and Steven E. Barton, her fifteen year old nephew who was serving in the military telegraph office.

But it was meeting General John J. Elwell of Cleveland, Ohio, chief quartermaster for the Department of the South, that rejuvenated her spirit. She and Elwell discovered that they shared many common interests and, though he was married, became close friends. For a while Clara felt a strong connection with someone for the first time in her life. Elwell found himself mesmerized by this witty, intelligent, and courageous woman, and encouraged their relationship despite the impropriety of the situation. Albeit unconventional in her thought and demeanor, as a realist Clara knew their relationship could not go beyond friends, and did not wish to break up Elwell's marriage, so neither pursued the other once their work on the island was terminated, though they would always remain fond of each other.

There are several websites and blogs that purport the photo at left is Clara Barton and John J. Elwell. Some even claim "confirmation" of this. All are pure wishful thinking and pure imagination.

Considering that Mathew Brady's famous portrait of Clara is also believed to have been taken in 1865, differences of their facial features are obvious--Clara had a much wider, rounder face, with eyes further apart, than that of the woman at left. Also, taking into account the evidence of the circumstances that Clara met and was with John J. Elwell, never having before met until their time at Hilton Head, it is even more conclusive that this is not Clara. And finally, knowing Clara's personality--her intense shyness which was with her all her life, she never would have flaunted such a relationship by have a portrait taken of herself with Elwell. As for her dress and hair style, this was the style and fashion of just about every woman of this social class in this time period. But if all this is not sufficient enough to convince, see this photo analysis.

In May, Clara met Frances D. Gage, and together they worked to educate former slaves and prepare them for their life beyond slavery. Here, Clara developed an interest in the growing movement for equal rights among women and African Americans.

On July 14, 1863, Clara moved from Hilton Head Island to Morris Island to tend the growing number of sick and wounded soldiers - a list that would greatly expand after the failed Union assault on Fort Wagner on July 18, 1863. Later in the Morris Island campaign, working out of her tent, she would seek to address the growing problem of sickness on the island by passing out fresh food and mail to the troops in the trenches. Despite her great efforts, Barton herself would become gravely ill and would be evacuated to Hilton Head island.

At the Siege of Ft. Wagner, South Carolina, August 10 - 11, 1863, Clara helped to establish field hospitals and distributed supplies following the failed assaults. She then returned to Washington, DC from January to May, 1864 to collect supplies and to recuperate. At the Battles of the Wilderness and Spotsylvania Court House near Fredericksburg, Virginia in May 1864, Clara arranged for the opening of private homes for the care of wounded with the assistance of Senator Henry Wilson, chairman of the Military Affairs Committee.

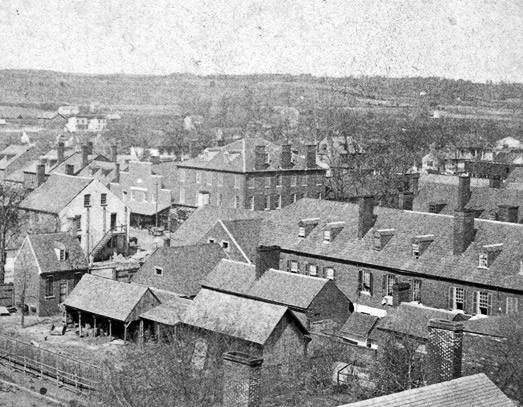

Planter’s Hotel - Planter's is the large square building in the middle distance, at the corner of Charles and George Streets.

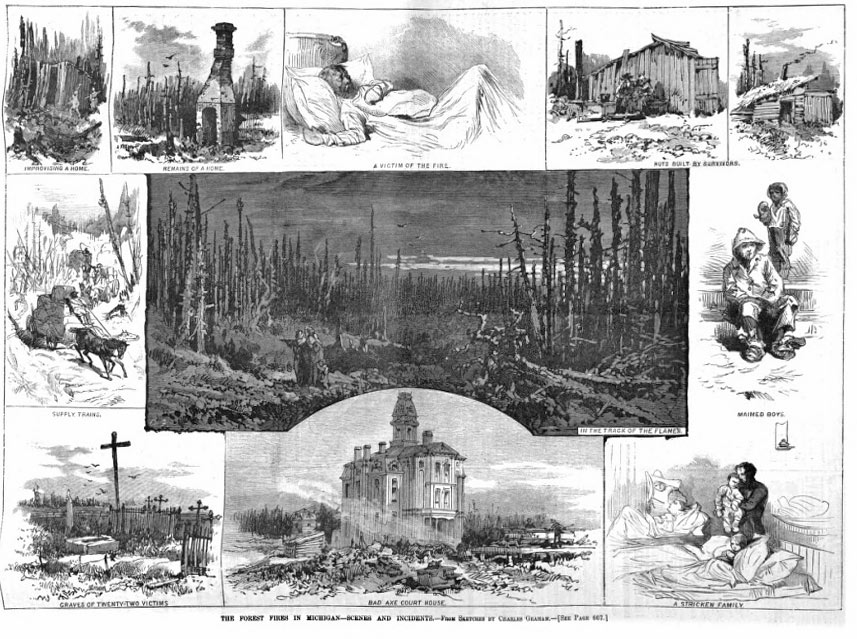

“I was struck with their fine soldierly figures and features remarkable even in terrible extremity,” wrote Barton, “and stopping by one I asked ‘where are you from—‘ ‘Michigan,’ and so on ‘Michigan,’ ‘Michigan,’ up one flight of stairs and another. Still ‘Michigan.’ At length in my surprise I said without reflection, ‘Did Michigan take up this hand and play it alone’? Yes, faintly answered a poor fellow at my feet wounded all over, who evidently understood better what he was saying than I did, ‘Yes, and got euchred.’ I thought he was correct.” From "Mysteries & Conundrums" National Park Service Fredericksburg in June 1864 continued to be an important hospital and logistical center for the Union Army, as wounded poured in from the overland campaigns advancing upon Richmond. From June 23, 1864 to 1865, Clara was placed in charge of diet and nursing at

an X Corps hospital near Point of Rocks, Virginia, appointed as superintendent of the nurses by Army of the James

Commander Major General Benjamin F. Butler The "flying hospital" served the

wounded from the almost daily fighting outside Petersburg. The International Red Cross established in Geneva, Switzerland

Stephen Barton, Jr. dies after capture and imprisonment by Union

In 1864, Clara's brother Stephen, who was standing vigil at his mill in Bartonsville, North Carolina, along with the families of Confederate soldiers in Hertford were beginning to suffer from want of supplies due to the blockade. Stephen Barton and a few sympathetic friends arranged to bring supplies from Norfolk in exchange for their own cotton. With a pass from Union officers who controlled the eastern side of the Chowan, Stephen himself made several trips by wagon into Pasquotank County, where Union agents purchased his cotton and gave him bacon and other commodities for distribution to the poor of Hertford County. On one such mission, Barton was arrested by Union authorities on suspicion of being a Confederate agent, imprisoned at Norfolk, and mistreated by prison officials. His health broke, and, by the time Clara was able to learn of his condition and have him freed, he was near death. He joined Clara at a field hospital near Richmond, and the two of them went to her home in Washington, D.C., where he died on March 10, 1865. Clara accompanied his remains to Oxford, Mass., where Stephen was buried in the Barton family cemetery. Three weeks later, on April 1, a Union cavalry patrol arrived at Bartonsville and, on the assumption that it was Confederate property, burned the entire establishment.

Clara appointed by President Lincoln to help locate missing soldiers and notify their families

In March 1865, with the assistance of Senator Wilson, Miss Barton won the approval of President Abraham Lincoln to address the problem of large numbers of missing soldiers. President Lincoln appointed her General Correspondent for the Friends of Paroled Prisoners. She reported to work on this task at the War Department in Annapolis. This department provided food, clothing, and assistance with correspondence for prisoners of war returning from Belle Isle and Andersonville, and also was responsible for recording the deaths of soldiers. Observing that the soldiers seemed the most knowledgeable on identifying the names of other soldiers—distinguishing the living from the dead—she thought to solicit their assistance. Clara published, posted, and distributed lists of the names of missing soldiers in sources such as newspapers and post offices, and at various organizations. She established The Office of Correspondence with Friends of the Missing Men of the United States Army on March 11. Recognition by the War Department followed two months later. She received an overwhelmingly positive response from the public, and helped to reunite countless soldiers with their loved ones. For four years her job was to respond to anxious inquiries from the friends and relatives of missing soldiers by locating them among the prison rolls, parole rolls, or casualty lists at the camps in Annapolis, Maryland. To assist in this enormous task, Barton established the Bureau of Records of Missing Men of the Armies of the United States and published Rolls of Missing Men to be posted across the country. Through this project, Clara was led to another project that called for the identification and formal burial of thousands of Andersonville prisoners.

End of the Civil War and Clara's involvement with the Army in identifying and burying the dead On

April 9, 1865, Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered to General Ulysses

S. Grant at Appomattox Court House, Virginia, signaling the end of the Civil

War.

In 1861 the War Department had issued orders directing the US Army Quartermaster General to assume responsibility for the burial and documentation of the nation's war dead. The first national cemeteries were established the next year in 1862. Between 1862 and 1871, the US Army Quartermaster created national cemeteries at battlefields, hospitals, and prison sites throughout the north and south. Many of these were established between April 1865 and 1871 as part of what was known as the Federal Reburial Program.

In the fall of 1865, U.S. Quartermaster General Montgomery Meigs ordered an assessment of the condition and location of graves to ensure their protection, an increasingly urgent issue in face of growing bitterness and defiance in the defeated South. Units of northern soldiers searched across the battle fronts of the war for slain Yankees, inaugurating what became over the next six years a massive federally supported reburial program. Ultimately, 303,536 Union soldiers were reinterred in 74 new national cemeteries, and Congress officially established the national cemetery system. Careful attention to the content of graves and to the documentation that poured in from families and former comrades permitted the identification of 54 percent of the reburied soldiers. Some thirty thousand of the reinterred were black soldiers. Just as they were segregated into the U.S. Colored Troops in life, so in death they were buried in areas designated “colored” on the drawings that mapped the new national cemeteries. Among these national cemeteries established by the US Army Quartermaster during the Federal Reburial Program was Andersonville. This federal effort included only Union soldiers. Outraged at the official neglect of their dead, white southern civilians, largely women, mobilized private means to accomplish what federal resources would not. In Petersburg, Virginia, for example, the Ladies Memorial Association oversaw the re-interment of 30,000 dead Confederates in the city’s Blanford Cemetery. What was to become the cult of the Lost Cause in the latter decades of the century found an origin in the rituals of Confederate reburials. The federal reburial program represented an extraordinary departure for the United States Government, an indication of the very different sort of nation that had emerged from civil war. The program’s extensiveness, its cost, and its location in the Federal Government would have been unimaginable before the war created its legions of dead, a constituency of the slain and their mourners, who would change the very definition of the nation and its obligations. The memory of the Civil War dead would remain a force in American politics and American life well into the 20th century and beyond. Civil War Era National Cemeteries: Honoring Those Who Served, National Park Service

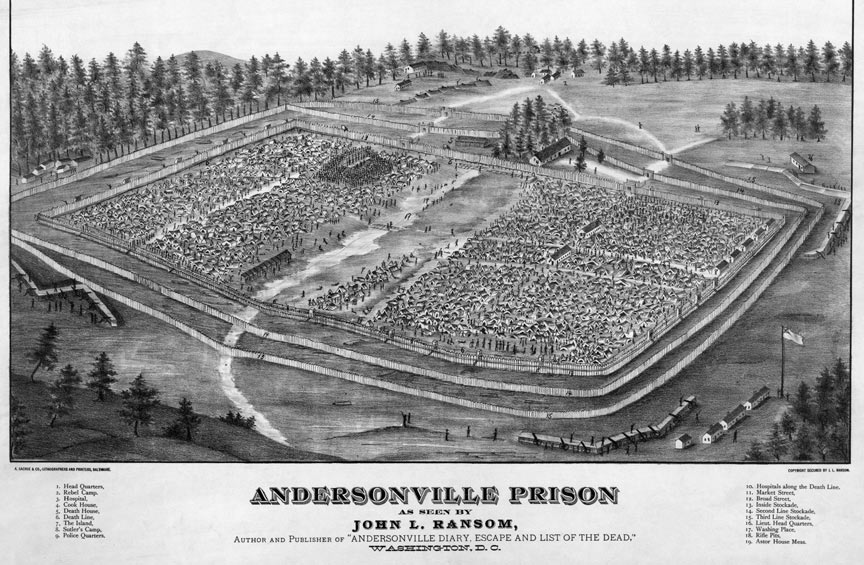

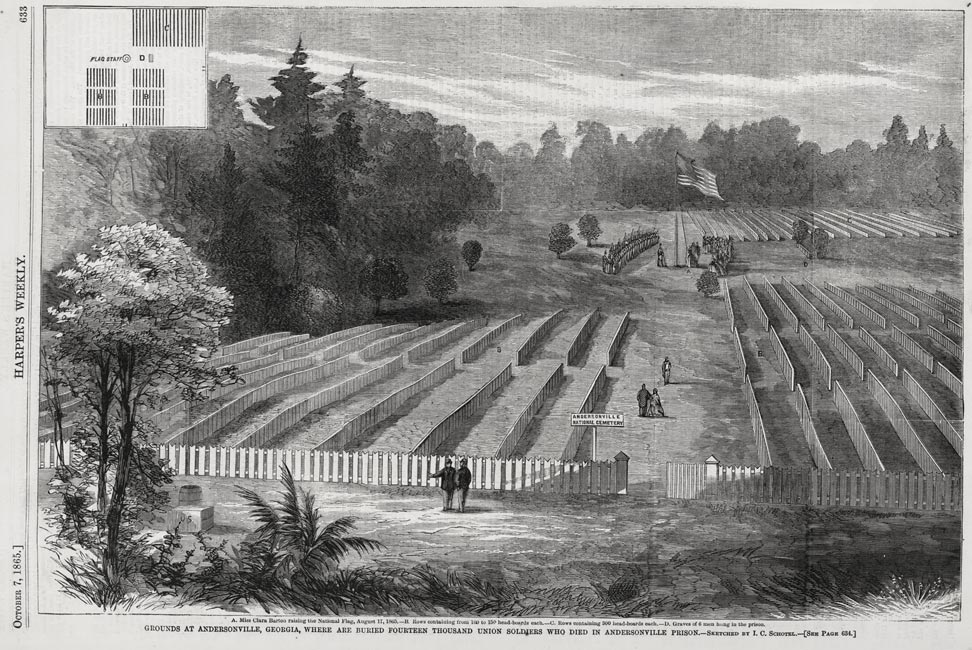

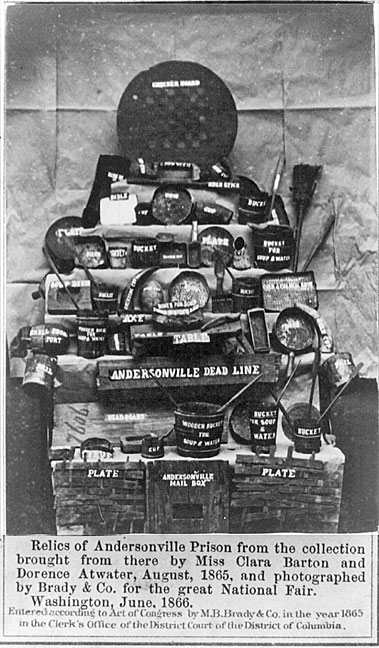

Clara Barton, Dorence Atwater, and the Andersonville Myth Andersonville, or Camp Sumter as it was known officially, held more prisoners at any given time than any of the other Confederate military prisons. It was built in early 1864 after Confederate officials decided to move the large number of Federal prisoners in and around Richmond to a place of greater security and more abundant food. During the 14 months it existed, more than 45,000 Union soldiers were confined here. Of these, almost 13,000 died from disease, poor sanitation, malnutrition, overcrowding, or exposure to the elements. Civil War Trust

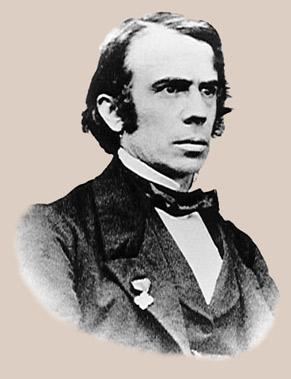

Paroled prisoners maintained lists of soldiers who died at Andersonville, and the burial crews ensured that the grave numbers on these lists corresponded with the grave number in the cemetery. Most famous among these was a young soldier from Connecticut named Dorence Atwater. When he left Andersonville in February of 1865, Atwater took copies of the burial list with him, and he turned these over to the army in the late spring of 1865. The Army Quartermaster office then used his list, combined with the Confederate copy that was captured at the prison hospital in May 1865, as the basis for documenting and identifying the graves. On June 22, 1865 Atwater wrote Barton a letter introducing himself to her, and asked for a copy of her missing soldiers lists, suggesting that he could provide information on many of those listed. Barton then contacted Secretary of War Edwin Stanton and asked that she be given access to the Atwater lists, which by this point were in the possession of the army and being copied. Granting her request for access, Stanton invited Barton to accompany the expedition, which left Washington, DC on July 8, 1865. The expedition to Andersonville was led by Captain James Moore, Assistant Quartermaster General, and veteran of the cemetery system. Moore had organized the burial efforts at Fort Stevens in 1864 and in the summer of 1865 he was assigned to lead expeditions to the Wilderness & Spotsylvania, which he did in June, and to Andersonville, which took place in late July and early August. After leaving Andersonville, Moore was assigned the responsibility for all cemeteries and burials in Virginia, and he also supervised the burial details at Antietam in preparation for the 5th anniversary of the battle. All total, Moore supervised the burial of more than 50,000 soldiers in cemeteries around the South. Moore and Barton bickered throughout the journey to and from Andersonville. For example, while staying in Augusta en route to the prison site, Barton complained that Moore refused to wait for her at dinner. Moore considered Barton a nuisance to the work, complaining, "Some people don't deserve to go anywhere. And what in hell does she want to go for?" The tension between the two combined with the popularity of Barton ensured that Barton's version of the story was what the public saw. Arriving at Andersonville on July 25th, the team worked with members of 137th USCT out of Macon, GA to physically replace the numbered headboards in the cemetery with proper headboards that listed each soldier's name, rank, unit, and date of death. By mid-August, nearly 13,000 graves were identified, with 400 graves marked "Unknown U.S. Soldier." With the help of Atwater, a total of 22,000 men would be identified before work on the missing soldiers project would come to a close. Fences and walkways were constructed and the graveyard at Andersonville was transformed into a national cemetery. Barton had access to the burial lists, and she spent much of her time responding to countless letters from loved ones. She also worked as a nurse for the work teams, several of whom became quite ill. Barton also spent a great deal of time meeting with area civilians, both black and white, discussing their thoughts about the prison and their plans for the future. On August 17, 1865 a small ceremony was held in the newly established Andersonville National Cemetery. Clara Barton was given the honor of raising the American flag during this service, which also featured the playing of the Star Spangled Banner. Barton later claimed that the expedition to Andersonville was her idea, and the Harper's Ferry illustration of her raising the flag helped fuel this perception.

Barton's work at Andersonville was important. The army had an efficient system for establishing these cemeteries, but it lacked a system for informing family members that a loved one died in service. Barton filled this role, and continued to do so long after she left Andersonville. Clara Barton collected relics at Andersonville and went on a national speaking tour raising awareness and funds for her work at the Missing Soldiers Office. National Park Service - Andersonville Myth

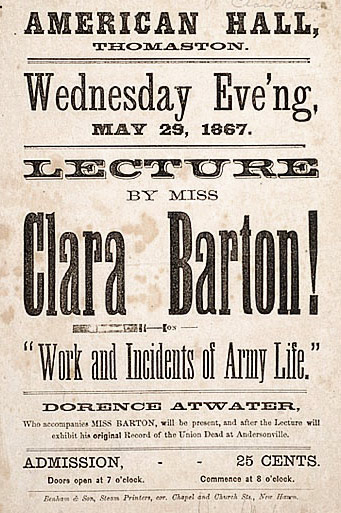

Clara Barton, the lecturer In the fall of 1866, at the suggestion of Fanny Gage, Clara embarked on an exhausting lecture tour. She began lecturing on her Civil War experiences in lyceum halls, churches, town halls and schoolrooms. Though she never felt comfortable in front of an audience, wherever she spoke she was well-received, and soon the tales of her work on the battlefields became widely known and even legendary. Clara was even asked to speak on behalf of women's rights, and at a Universal Franchise Convention in 1868 proclaimed that blacks had suffered far greater wrongs than women in their oppression. Her contemporary biographer Percy Epler wrote that “a tear-stained multitude thronged everywhere to hear her,” for she made it her mission to show, as she said, not “the glories of conquering armies but the mischief and misery they strew in their tracks; and how, while they march on . . . some one must follow closely in their steps, crouching to the earth . . .faces bathed in tears and hands in blood. This is the side which history never shows.” On February 21, 1866, Clara testified during the 39th Congress about her experience in Andersonville. On March 10, Congress appropriated $1500 (according to her obituary) to reimburse Miss Barton for expenses associated with her search for missing men.

From 1866 through 1868, Clara delivered over 200 lectures throughout the northeast and Midwest regarding her Civil War experiences. She shared platforms with other prominent figures including Frederick Douglass, Ralph Waldo Emerson, William Lloyd Garrison, and Mark Twain. She often earned $75 to $100 per lecture. It was during these lecture tours, on November 30, 1867, that Clara met Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. The resulting friendships aligned Miss Barton with the suffrage movement. Clara lost her voice in Dec. of 1868 from fatigue and mental prostration while delivering a speech. In 1869, Clara closed the Office of Correspondence with

Friends of the Missing Men of the United States Army, having received and

answered 63,182 letters and identified 22,000 missing men.

Clara in Europe - Geneva, Switzerland

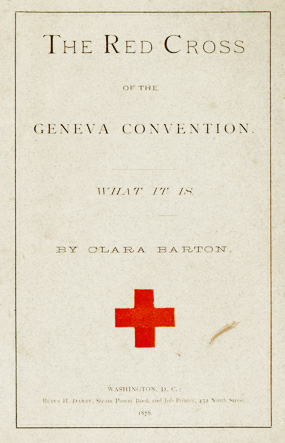

On the advice of her doctor, in September of 1869, when she was 48, Clara traveled to Europe for a much needed rest. She embarked on a whirlwind tour with her sister Sally, and remained overseas even after Sally returned home to the United States. While in Switzerland, Clara was visited by Dr. Louis Appia of the International Convention of Geneva. He had heard of Clara's work during the Civil War and hoped that she could persuade the U.S. government to acknowledge the articles of the Geneva Convention.

Twelve nations originally ratified the Treaty of Geneva. These articles—which legally bound the signatory nations to an agreement that impartial relief would be provided to the wounded, sick, and homeless during wartime—formed the basis of the International Red Cross, organized during conferences held in 1863 and established in 1864 by Swiss businessman (Jean) Henri Dunant. In 1859, Dunant had witnessed the horrors of the bloody aftermath at the Battle of Solferino, Italy, and was inspired by the compassionate acts of the peasant women who bound the wounds of their soldiers as well as the enemy's while murmuring that "all are brothers." Miss Barton was amazed to learn that the United States government had rejected the idea of the war relief organization and had not joined, even while she toiled as a private citizen to supply the needs of the wounded on the American battlefields during the Civil War. Clara was inspired to push for the adoption of both in the United States.

The Biography of Clara Barton: Birth of the Red Cross National Park Service Manuscript

Dr. Louis Appia photo and info from Wikipedia

Clara in Europe - The Franco-Prussian War

On July 18, 1870, Napoleon III declared war on Prussia and its German allies, thus starting the Franco-Prussian War. Miss Barton worked under the sponsorship of the International Red Cross and the German Red Cross. During this service, on September 17, 1870, Clara met and established a lifelong friendship with the Grand Duchess Louise of Baden (Germany), the daughter of Kaiser Wilhelm I and the Empress Augusta. She was a noted philanthropist and was credited with founding the German Red Cross, advocated women working in disaster relief, and supported the establishment of nursing schools. Their friendship had a lifelong influence on Clara.

The Grand Duchess gave Clara her first Red Cross pin, issued her a railroad pass and sent her to the besieged city of Strasbourg, France. Miss Barton wore this pin throughout her second war relief experience, the Franco-Prussian War. There in Strasbourg, under the sponsorship of the Grand Duchess, Clara met Antoinette Margot, who became her co-worker, travelling companion, and translator. In Strasbourg, they organized relief efforts and established sewing factories in order to provide clothing for the residents and employment for women.

Clara's work with the Red Cross during the Franco-Prussian War contributed to her international legacy. Kaiser Wilhelm I and the Empress Augusta recognized Miss Barton's accomplishments and honored her contributions to the war relief efforts with several awards. The Grand Duke and Duchess of Baden also accorded Miss Barton official recognition and presented her with awards and gifts.

The amethyst pansy brooch (bottom right) and smoky topaz (bottom center) brooch presented to Clara by her dear friend, the Grand Duchess Louise, became her most cherished possessions.

Clara Barton A Lifetime of Service, The National Park Service, Clara Barton National Historic Site

Bottom pin is the Red Cross of Sebia, awarded in gratitude for Balkan War relief in 1885.

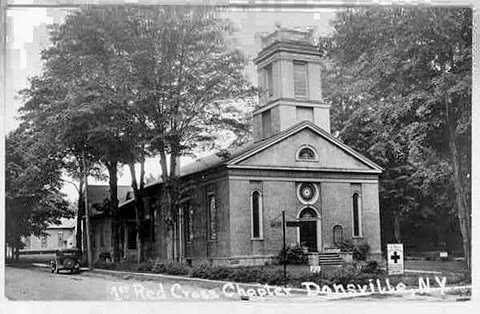

Clara directed relief work in Paris for six weeks in 1871, establishing workrooms in Lyon, and providing assistance in Besancon and Belfort. From 1872 to 1873, she suffered from nervous exhaustion and temporarily lost her eyesight. She traveled to England in an attempt to recuperate.