|

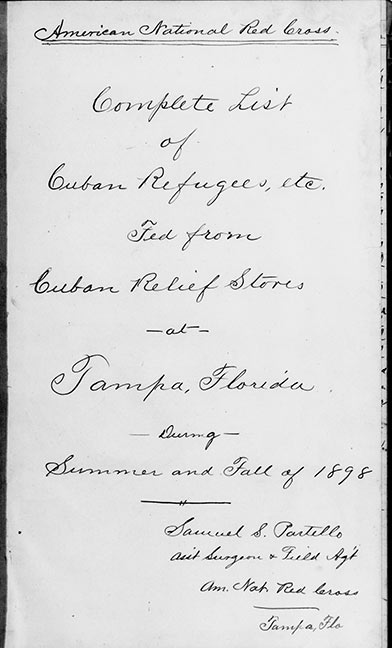

The Plight of the Cuban

Concentration Camp Prisoners

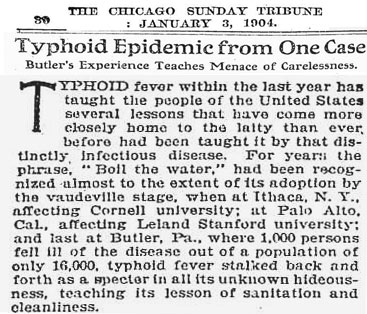

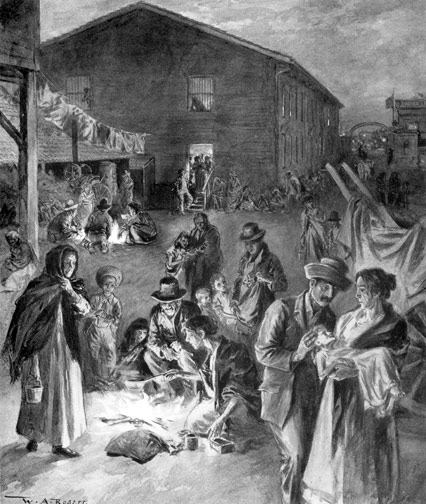

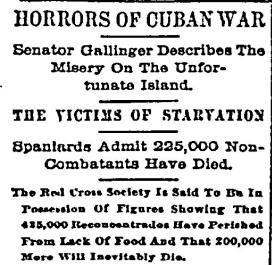

During Cuba's struggle for independence from Spain, hundreds of thousands

of Cuban peasants were forced from their homes and herded in to

concentration camps. In an 18-month period from 1896 to 1897, over

225,000 civilians died, mostly of starvation. The Red Cross was reported

to have statistics showing 425,000 perished from starvation and 200,000

more would die.

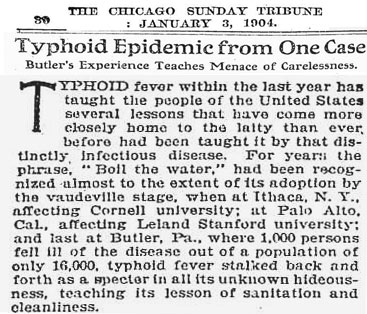

See article.

In the midst of bringing Red Cross aid to those suffering through

disasters at home and abroad, news of the Cuban reconcentrados plight

distressed Barton. She believed that the Red Cross was a “direct

servant of the government,” therefore, without President William

McKinley’s permission, Barton would not endorse any Red Cross involvement.

From The Spanish American War

Centennial Website

Links to newspaper articles from 1897 and 1898 describing the horror of

the camps. Caution: Graphic images.

Weyler's Reconcentration Policy and its Horrors

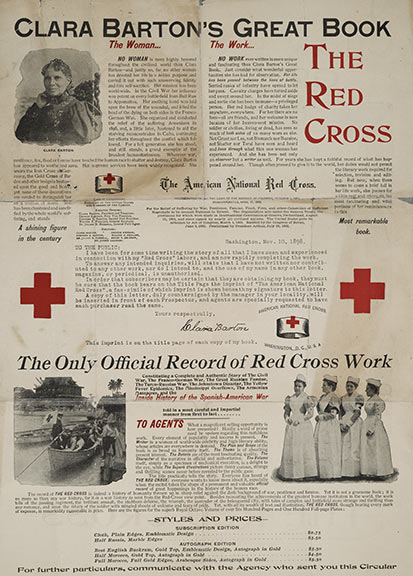

"The Red

Cross in Peace and War" on the plight of the Cubans

|

|

|

Maria Christina Henriette Desideria Felicitas Raineria von

Habsburg-Lothringen

of Austria (21 July 1858 – 6 February 1929) was Queen of Spain

from November 1885 to May 1902 as the widowed second wife of

King Alfonso XII. She was regent during the vacancy of the

throne between her husband's death and her son's birth and during

the minority of their son, Alfonso XIII.

Photo and info from Wikipedia. |

We had scarcely returned from Armenia when paragraphs began to appear in

the press from all sections of the country, connecting the Red Cross with

some undefined method of relief for Cuba. These intimations were

both ominous and portentous for the future, something from which we

instinctively shrunk and remained perfectly quiet. “The murmurs grew to

clamors loud,” and, I regret to say, not always quite kind.

Tired, heart-sore and needing rest, we were compelled to read columns of

such reports, and understanding that it was not without its political side

and might increase to proportions dangerous to the good name of the Red

Cross, we felt compelled to take steps in self-protection.

Accordingly, through the proper official authorities of both nations, we

addressed to the government of Spain at Madrid a request for royal

permission for the American Red Cross to enter Cuba and distribute,

unmolested, among its starving reconcentrado population such relief as the

people of America desired to send.

This communication brought back from Spain perhaps the most courteous

assent and permission ever

vouchsafed

by a proud government to an individual request, especially when that

request was in its very nature a rebuke to the methods of the government

receiving it. Not only was permission granted by the crown, the

government, the Captain-General at Cuba, and the Queen Regent, but to the

assent of the latter were added her majesty’s gracious thanks for the

kindly thought.

From The Red Cross in Peace and War by Clara Barton

|

|

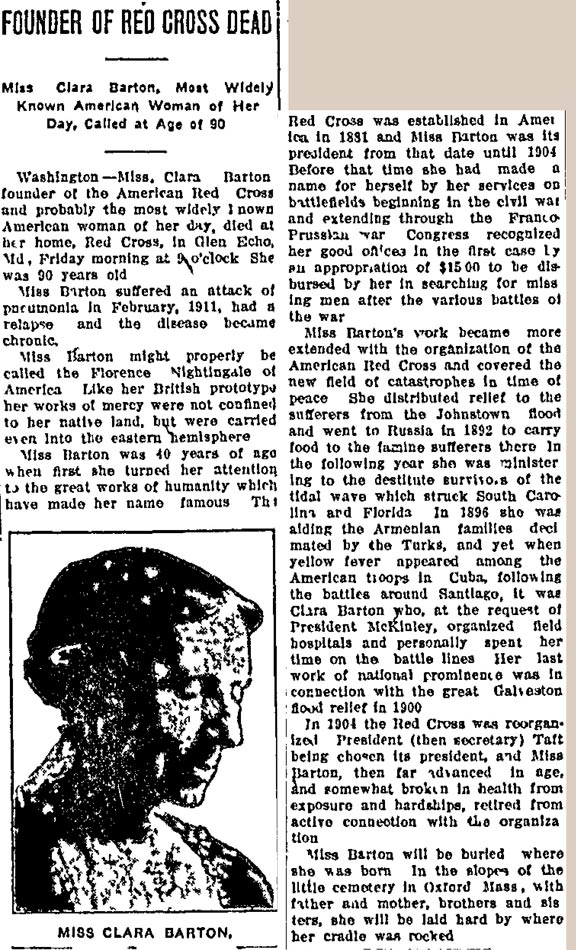

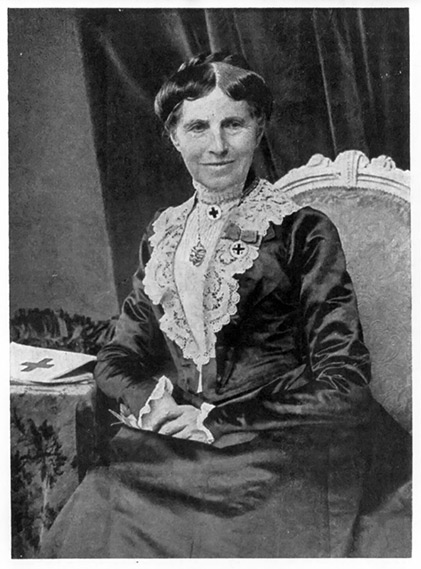

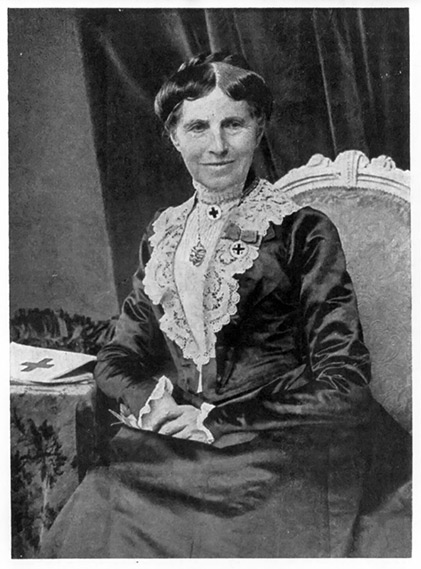

Clara

Barton, 1897 |

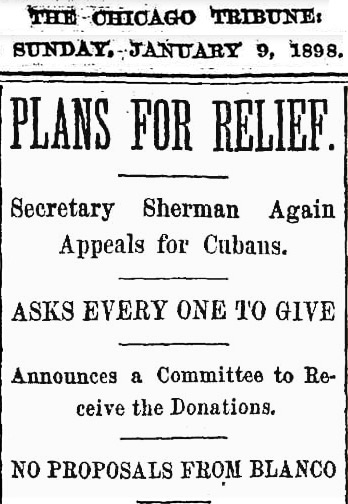

Formation of the President's Committee for Cuban Relief

Those who were impatient for Red Cross action included Cuban patriots. In

a gripping letter, they attacked Barton and the Red Cross for inhumanity

towards the reconcentrados. As the summer of 1897 wore on, no longer able

to quietly bear the reports, Barton requested that “the Red Cross take

steps on its own in direct touch and with the cooperation of the people of

the country.” Illustrating her ease of communication with the President,

she called on him at the White House and joined the conference in progress

with his Secretary of State.

From The Spanish American War

Centennial Website

Clara wrote in "The Red Cross in Peace and War"

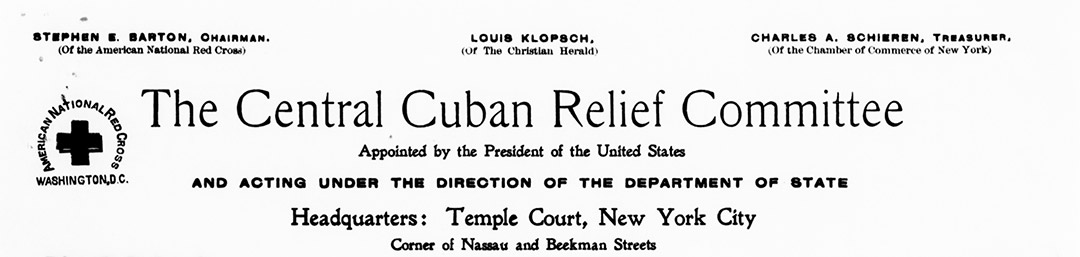

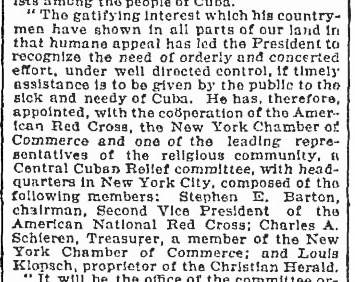

The conference was then held. It was decided to form a committee in New

York, to ask money and material of the people at large to be shipped to

Cuba for the relief of the reconcentrados on that island. The call would

be made in the name of the President, and the committee naturally known as

the “President’s Committee for Cuban Relief.” I was courteously asked if I

would go to New York and assume the oversight of that committee. I

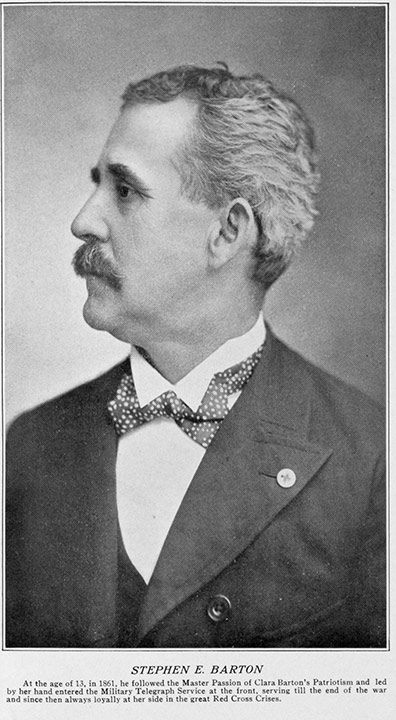

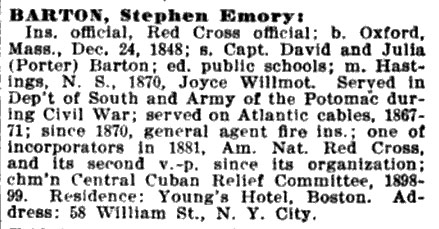

declined in favor of Mr. Stephen E. Barton, second vice-president

of the National Red Cross, who, on being immediately called, accepted; and

with Mr. Charles Schieren as treasurer and Mr. Louis Klopsch,

of the Christian Herald, as the third member, the committee was at once

established; since known as the Central Cuban Relief Committee.

The committee was to solicit aid in money and material for the suffering

reconcentrados in Cuba, and forward the same to the Consul-General at

Havana for distribution.

|

|

|

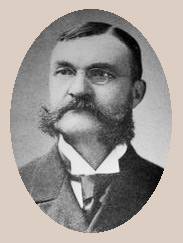

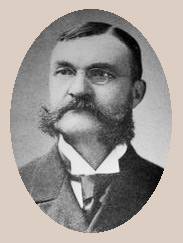

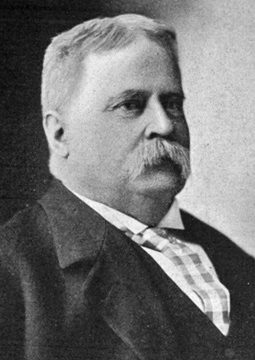

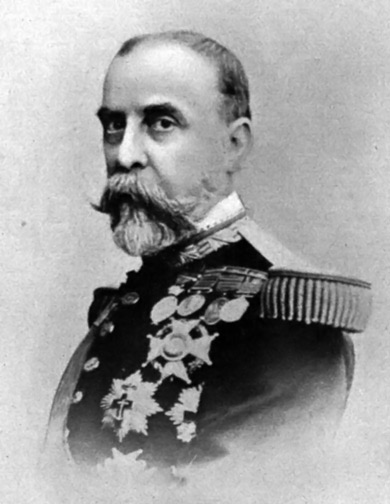

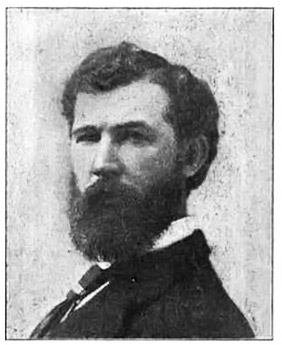

Charles Adolph Schieren

He had served as Mayor of the City of Brooklyn from 1894 through

1895 and was a successful businessman in the leather

belting industry. |

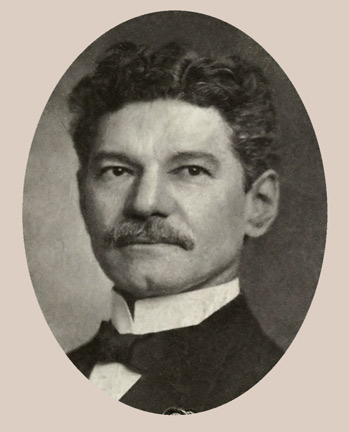

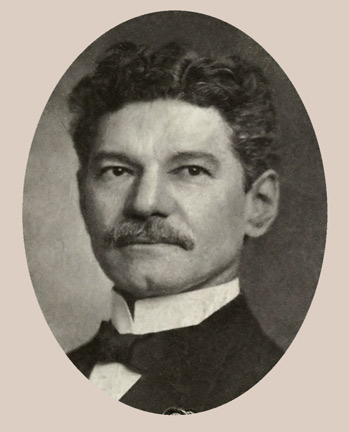

Louis Klopsch, editor of the Christian Herald, is credited for

conceiving the idea of printing the words of Jesus in the Bible

in red in 1899 and publishing the first red-letter New Testament

the same year. |

My consent was then asked by all parties

to go to Cuba and aid in the distribution of the shipments of food as

they should arrive. After all I had so long offered, I could not

decline, and hoping my going would not be misunderstood by our

authorities there, who would regard me simply as a willing assistant, I

accepted. The Consul-General had asked the New York Committee to

send to him an assistant to take charge of the warehouse and supplies in

Havana. This request was also referred to me, and recommending Mr. J.

K. Elwell, nephew of General J. J. Elwell, of Cleveland,

Ohio, a gentleman who had resided six years in Santiago, Cuba, in

connection with its large shipping interests, a fine business man and

speaking Spanish, I decided to accompany him, taking no member of my own

staff, but going simply in the capacity of an individual helper in a

work already assigned.

From The Red Cross in Peace and War by Clara Barton

Clara heads to Cuba from Washington, via

Jacksonville, Tampa & Key West, finds appalling conditions

Clara's diaries & journals at the Library of Congress

record for this period before she left for Cuba, entries from Sept. 10,

1897 to Jan. 29, 1898--her time in New York, Washington DC, and her home

in Glenn Echo, MD. Her last entry on Jan. 29th reads:

Cold,

windy day. Coldest day. Had to go to town again to get my

tooth set right. Dr. Chase ill, Dr. Wolf set my tooth in place.

Took with me checks to cash.

(In different handwriting)

Too late for bank, closed at 12 Sat. Could only go to dentist and come

home. Did not know what to do or say about S.P.

See journal entry

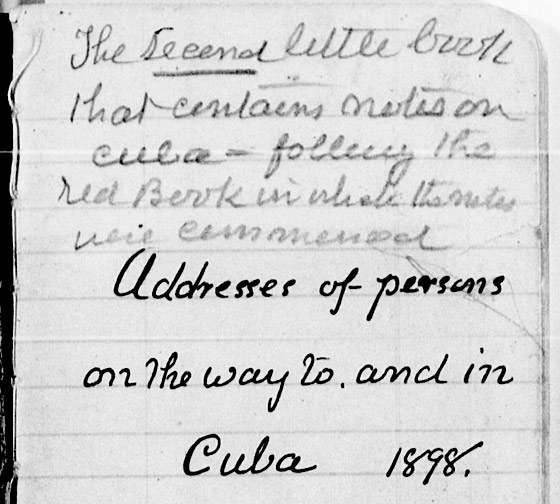

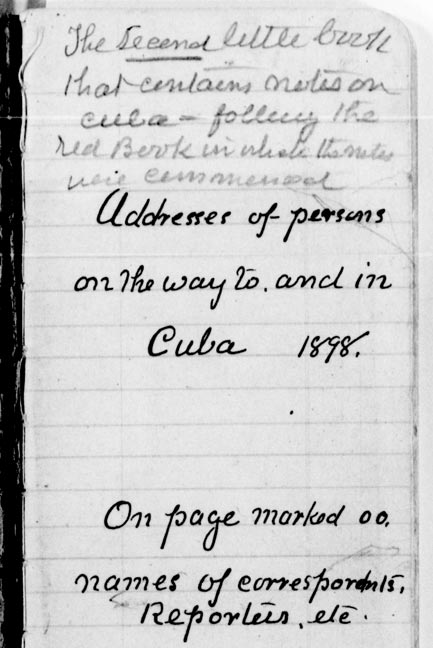

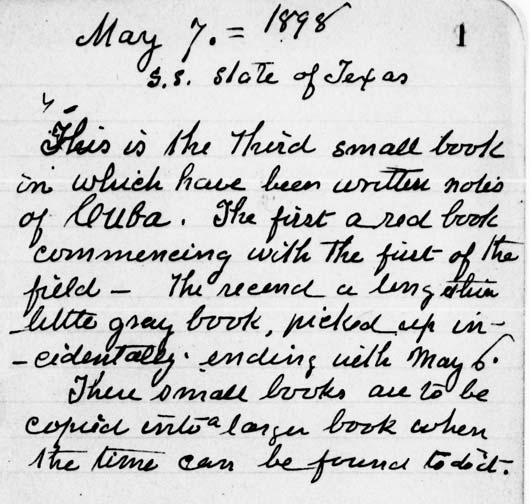

The first journal covering involvement in Cuba

The journals covering

Clara's involvement in Cuba are numbered, but No. 1 has not been located.

There is a gap in dates from Jan. 30 to Feb. 25, 1898, the period between

the previously mentioned journal and the journal marked "2" which begins

with Feb. 26, 1898. On the first page of this No. 2 book, she

refers to the previous book as her red book in which her notes on Cuba

commenced. It is assumed that this No. 1 book would contain Clara's notes

on her trip from Washington to Cuba, through Tampa, her arrival

in Cuba, and the events of the battleship Maine explosion.

Bruce Kirby, a reference

librarian in the manuscript division at the Library of Congress, recently

viewed the original books in the collection and confirmed that the journal

covering the dates February 26 to May 6 is numbered “2," the journal

beginning May 7 is numbered “3," and so on through the volume ending March

31, 1901, which is numbered “7.” There is no indication in the box

of the whereabouts of "No. 1” which presumably would cover the missing

dates January 29 to February 26, 1898.

Mr. Kirby also said, "It

is possible, though not likely, that the volume could have been mistakenly

placed among the Spanish-American War subject files in the series

“American National Red Cross” in boxes 116 to 148 of the Barton papers in

the Manuscript Division. In addition, the volume might be among the

official records of the Red Cross that are held by the National Archives

and Records Administration. One of Barton’s biographers, Elizabeth

Brown Pryor, found a reference to the lunch with Captain Sigsbee in a

Barton letter now located in the Red Cross records at NARA. See

Clara Barton: Professional Angel, (Philadelphia, University of

Pennsylvania Press, 1987), p. 303.

Finally, one Library of

Congress historian hypothesized that the volume may have been used during

the investigation into the sinking of the U.S.S. Maine on 15 February

1898, and may now be part of the investigation files.

"The

second little book that contains notes on Cuba -

following the red book in which the notes were commenced"

The Red

Cross Correspondence Books

Though her first journal

(No. 1) containing information on her first trip from Washington to Cuba

has not been located, it is possible to determine when Clara passed

through Tampa for the first time. These letters from the collection of

Red Cross correspondence books of 1898 at the Library of Congress

discuss Clara's travel arrangements with the Plant System.

Even before Clara

travelled to Cuba through Tampa, the committee for relief of Cuban

concentration camps was already seeking help from H. B. Plant and his

transportation system for their supplies to Cuba.

See this Jan. 27, 1898 letter from Plant

to Stephen Barton, Committee Chairman, declining his request for free

transportation of supplies on the Plant System.

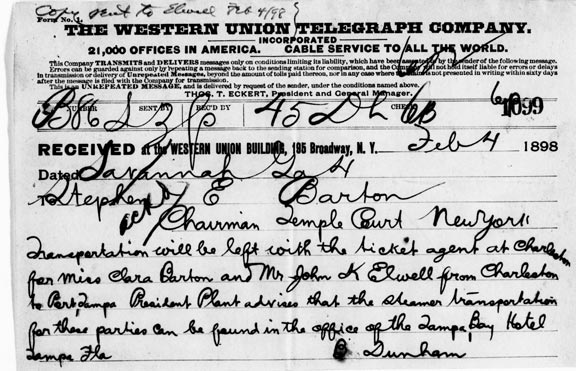

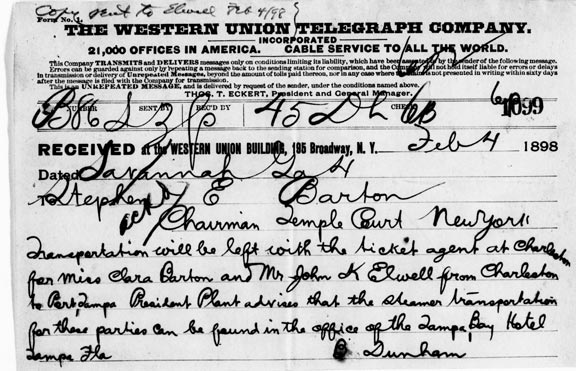

Feb. 4, 1898 Telegram to

Stephen E. Barton confirming that transportation will be left with the

ticket agent at Charleston, SC, for Miss Barton and John Elwell from

Charleston to Port Tampa. President Plant advises that the steamer

transportation passes for these parties can be found in the office of the

Tampa Bay Hotel.

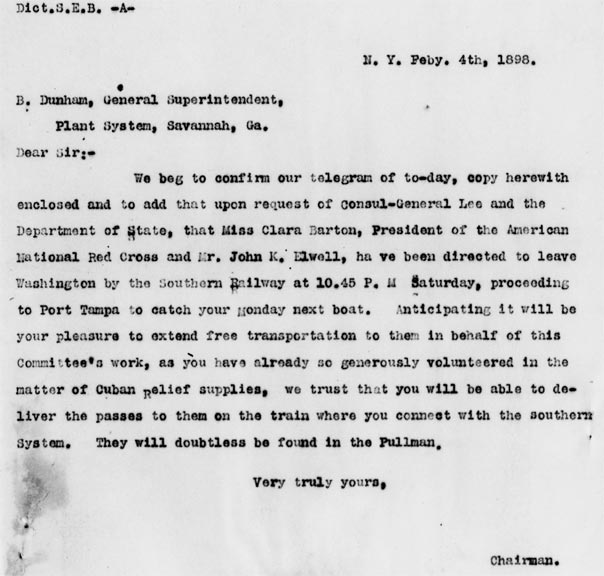

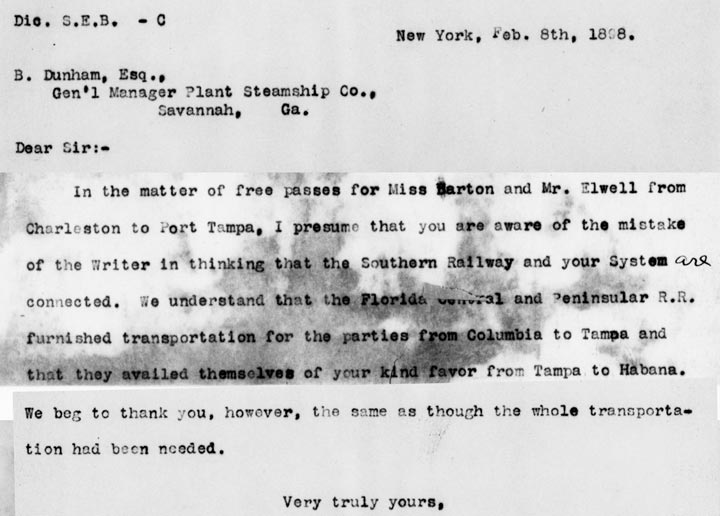

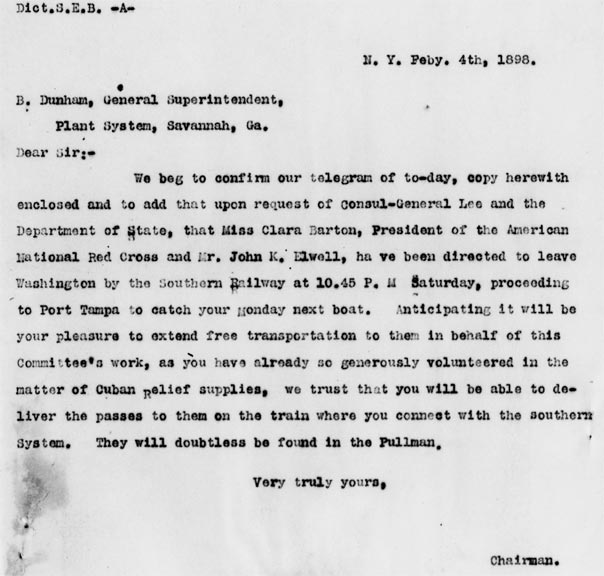

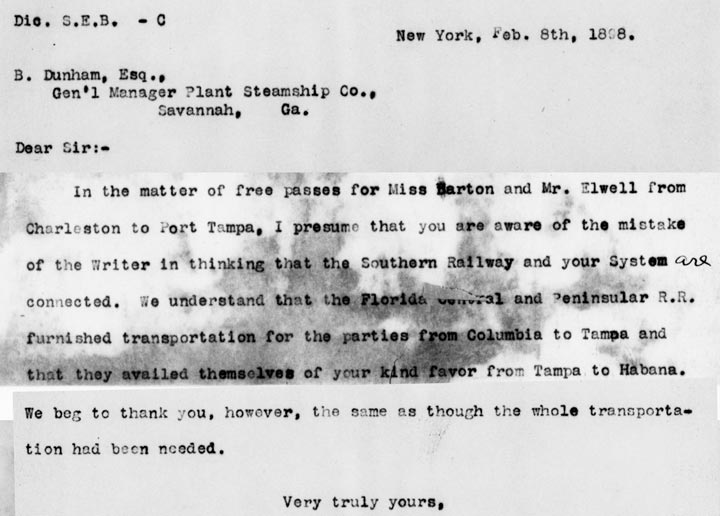

This letter, dictated by

Clara's nephew, Chairman of the committee for Cuban Relief, Stephen E.

Barton, states that Clara and John Elwell were leaving Washington DC on

the Southern Railway at 10:45 pm Saturday. (Feb. 5), proceeding to Port

Tampa to catch a boat on Monday (Feb. 7.)

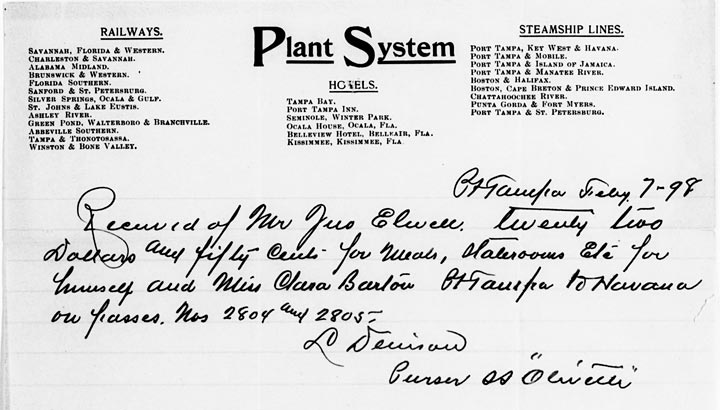

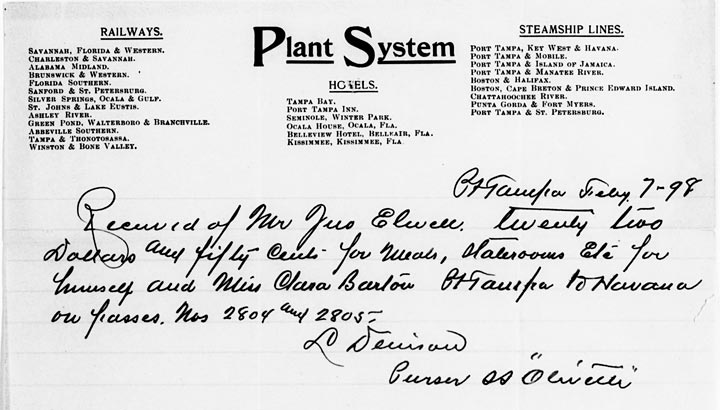

This receipt for $22.50 on

Feb. 7, 1898 is for payment to the purser of the SS Olivette for John

Elwell and Clara Barton's meals, staterooms, etc. in passage from Port

Tampa to Havana.

This letter dictated for

telegram by Stephen E. Barton to the general manager of the Plant

Steamship Co., condensed from 2 pages and edited to remove

irrelevant information, shows SEB assumed that the Plant System railroad

would have carried Clara and Elwell all the way to Port Tampa with Plant's

free passes, but in fact this was not so. They had to ride the C&S

Line from Charleston to Savannah, then the Florida Central and Peninsular

Railroads from Savannah to Tampa--an indication that the trip would have

taken a full two days and there was no time spent overnight in any hotels.

Southern Railway and the Plant System in the

late 1890s

|

|

|

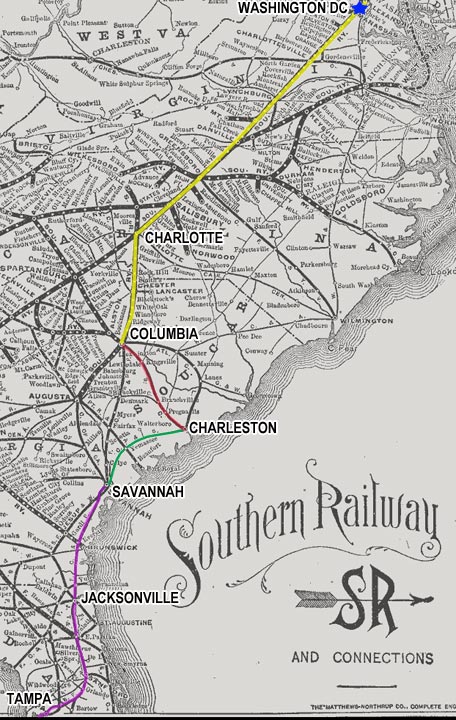

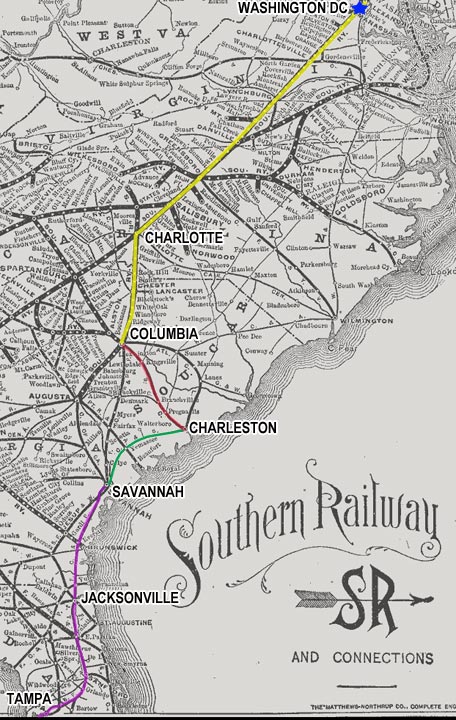

This 1895 Southern Railway map shows the most probable route Clara

would have taken. The yellow marks the route from Washington,

DC to Columbia, SC on the Southern Railway System.

The red on

the South Carolina Railway** from Columbia to Charleston, SC

where she and Elwell picked up their tickets for the route from

there to Tampa. Then the Charleston & Savannah line (green), and

from Savannah to Tampa, the Florida Central & Peninsular Railroad

(purple.)

|

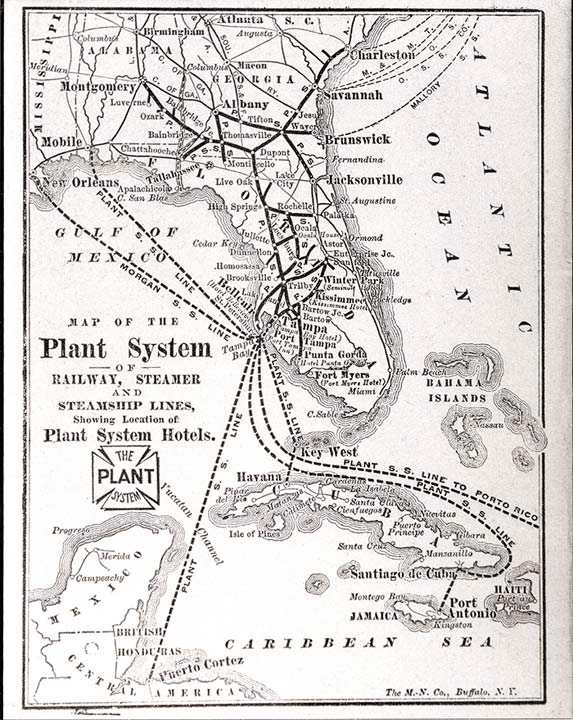

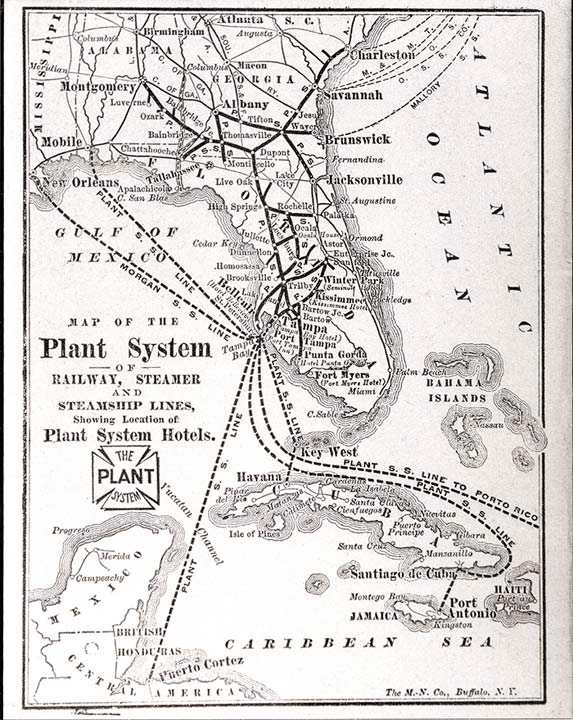

The Plant System in 1896,

courtesy of

Cigar City Magazine.

Plant’s transportation system included both trains and steamships

for passenger transport. Hotels were a logical extension of this

system. The shallow draft of Tampa Bay made Tampa's main port

inaccessible for the larger ships of the day, so Plant built a new

port several miles away on the west coast of Tampa's Interbay

peninsula. When Plant extended his railroad tracks to Port Tampa, he

also built in 1885, an inn at the wharf for passengers since there

were no previously existing hotels nearby. Not to be confused with

the Port of Tampa, Port Tampa City was the lands west of today's

Manhattan Avenue to Tampa Bay and everything south of the old

east-west railroad track north of McCoy Street.

|

The absence of any receipts or or other communications

regarding stays in hotels, it appears that Clara Barton and John Elwell arrived in

Tampa at the Tampa Bay Hotel train station on Monday, Feb. 7, picked

up their Plant System steamer passes for the Olivette and promptly

boarded it in Port Tampa for their trip to Cuba, most likely via Key

West, as the Plant System steamer lines typically did.

**Special thanks to the

South

Carolina Railroad Museum on Facebook

for identifying this railway line. |

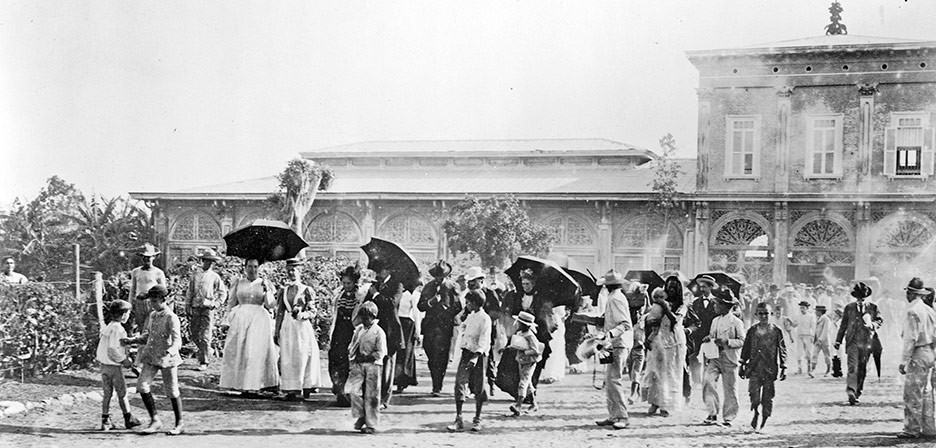

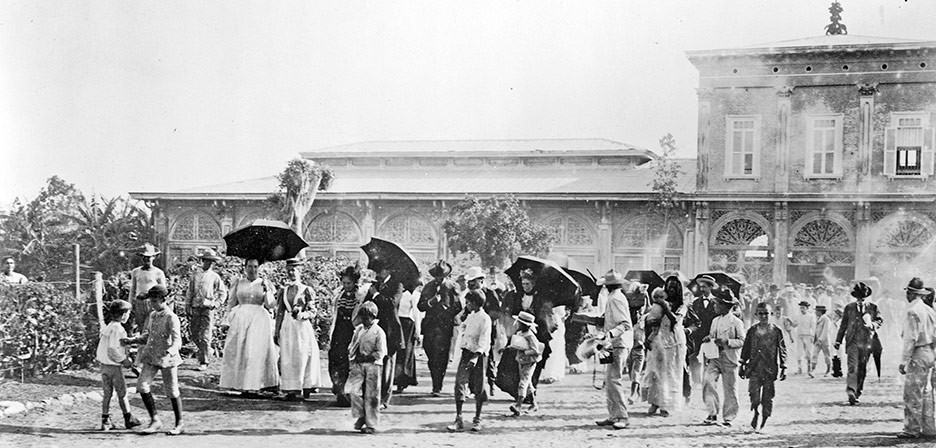

Clara arrives in Cuba

Later in her

book,

The Red Cross in Peace and War, on page 520 she would write:

"We reached Havana

February 9, five weeks ago, and in all the newness of a strange

country with oriental customs, commenced our work." The above

entry I find in my diary.

In speaking of conditions

as found, let me pray that no word shall be taken as a criticism upon

any person or people. Dreadful as these conditions were, and rife as

hunger, starvation and death were on every hand, we were constantly

amazed at the continued charities as manifested in the cities, and

small, poor villages of a people so over-run with numbers, want and

woe for months, running into years; with all business, all

remuneration, all income stopped, killed as dead as the poor, stark

forms around them, it was wonderful that they still kept up their

organizations, municipal and religious, and gave not of their

abundance, but of their penury; that still a little ration of food

went out to the dens of woe. That the wardrobe was again and again

parceled out; that the famishing mother divided her little morsel with

another mother’s hungry child; that two men sat down to one crust, and

that the Spanish soldier shared, as often seen, the loaf—his own half

ration—with the eager-eyed skeleton reconcentrado, watching him as he

ate. In another instance the recognition might have been less kind it

is true, for war is war, and all humanity are not humane.

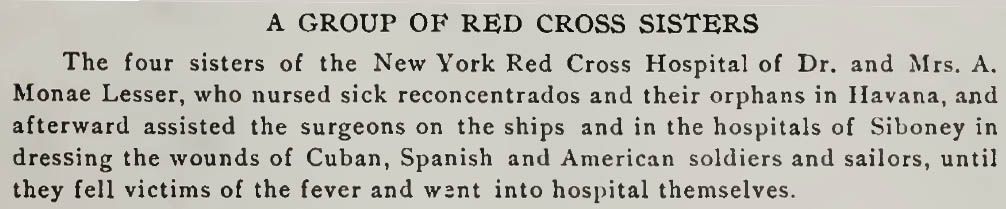

Clara set to work visiting

sites where the Red Cross could arrange distribution centers. The Red

Cross hospital’s chief nurse Bettina Hofker-Lesser, Dr. Adolph

Monae-Lesser and four nurses from the then-closed Red Cross Hospital

followed Barton to Cuba to support her work.

The Red Cross in Peace and War by Clara Barton

The Spanish American War

Centennial

Clara Barton with Red Cross

nurses and staff on a street in Cuba, 1898

Place your cursor on the photo to see enlargement and Clara identified by

a +

Photo

courtesy of Library of Congress

Clara

Barton onboard the battleship USS Maine

|

|

|

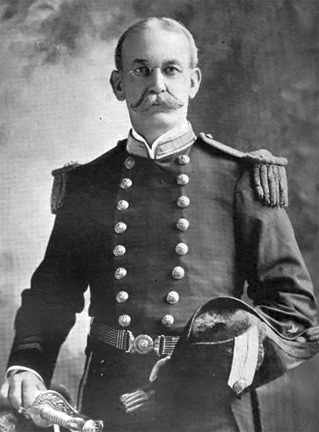

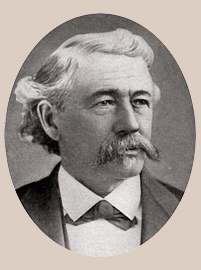

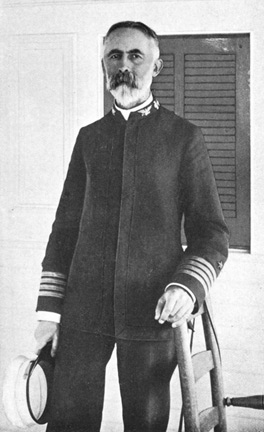

Fitzhugh Lee, Gen.

Consul to Cuba. Photo from Library of Congress

|

Because of propaganda from the U.S. newspapers and the Cuban insurgents,

the situation in Cuba was not fully understood in Washington DC. The U.S.

Consul in Havana,

Fitzhugh Lee, was also somewhat out of touch with the country in which

he was living. President Grover Cleveland had appointed him consul general

in 1896, a position he retained even after the election of President

McKinley.

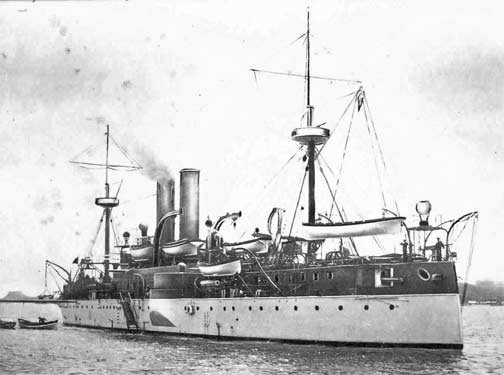

In response to a small protest by Spanish officers, not affecting the

United States, Washington sent the USS Maine, under the command of Capt.

Charles Sigsbee, to Cuba on a "friendly" visit. A few hours after

the President ordered the USS Maine to Havana Harbor, Lee telegraphed his

advice not to send such a ship.

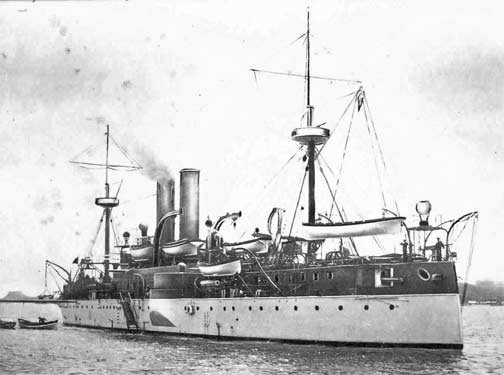

The Maine arrived in Cuba's Havana harbor on January 25, 1898 at which

time Captain Sigsbee found the city relatively quiet.

The Spanish American War

Centennial

The battleship USS Maine

entering Havana Harbor, Jan 25, 1898.

Photo from Wikipedia.

On Sunday, Feb. 13, 1898,

Captain Charles D. Sigsbee invited Clara to come aboard. Born in

1845, Sigsbee was a full generation younger than Barton, but he knew her

story very well, as did most Americans. Sigsbee had served in the

Civil War after graduating from the Naval Academy at Annapolis in 1863,

and he knew that Barton had been one of the most instrumental figures of

the great conflict. Clara accepted Sigsbee's invitation and sometime

in the afternoon, she went aboard the Maine.

Later in 1899, in her book "The

Red Cross in Peace and War," Clara wrote:

A

cordial invitation from Captain Sigsbee to visit the "Maine" that

afternoon had been received. His launch courteously came for us;

his officers received us; his crew, strong, ruddy and bright, went

through their drill for our entertainment, and the lunch at those

polished tables, off glittering china and cut glass, with the social

guests around, will remain ever in my memory as a vision of the "Last

Supper."

|

|

|

Stern view of the Maine - Photo from Wikipedia

|

There were no photographs taken nor any record made of their conversation.

Clara's journal which contained her notes on the Maine explosion may have

been confiscated for use in the investigation.

Sigsbee may have given Clara a tour of the clean, swept deck of the Maine,

but probably not one of its grimy, soot-infested hold. Although she

had spent a lifetime in the service of sick and wounded soldiers, Clara

often confessed a weakness for some of the trappings of military and naval

power. The Maine, with its turrets, guns and engines, must have made

a strong and positive impression. Few Victorian ladies went on board

battleships in those days, and Clara may well have savored the moment.

They probably discussed the condition of the people of Havana. Clara

had arrived only four days earlier and did not know all of the details,

but she was convinced that the reconcentrados had suffered the most as a

result of the Spanish-Cuban war. Captain Sigsbee may have been

sympathetic to their plight, but as a Navy officer, his mission was to

keep the peace in Havana Harbor, not to assist the victims of the war.

All that is known for certain is that Clara spoke with another officer,

the second-in-command of the Maine, and offered him and his men her

assistance if anything should happen to them. The officer's response

is not recorded, but he probably smiled, for what danger could befall the

Maine? Going ashore, Clara returned to her work.

Two days later, on the evening of Feb. 15, Captain Sigsbee had retired to

his cabin to write a letter. He wrote to his wife that he heard the

bugler play Taps. Then at 9:40 pm, the force of an explosion

startled him.

Maine officers, 1896. Library of Congress Control #: 2016795115.

The

Explosion on the USS Maine

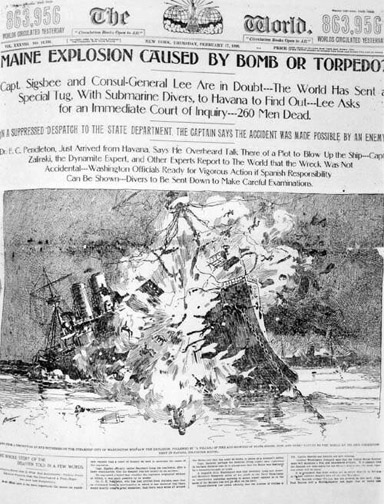

On the

evening of February 15, 1898, the American battleship Maine exploded

while sitting in the Havana harbor, killing two officers and 250

enlisted men. Fourteen of the injured later died, bringing the death

toll to 266. Sent to protect U.S. interests during the Cuban revolt

against Spain, she exploded suddenly, without warning, and sank

quickly.

In 1898, an

investigation of the explosion was carried out by a naval board

appointed under the McKinley Administration. The consensus of the

board was that the Maine was destroyed by an external explosion from

a mine. However, the validity of this investigation has been

challenged. Release of the board’s report led many to accuse Spain

of sabotage, helping to build public support for war.

|

|

|

|

American

propaganda postcard showing Union and Confederate soldiers

shaking hands in front of a female personification of Cuba

with broken shackles, circa 1898. The rallying cry of

"Cuba Libre" originated with the Cuban independence movement

and became wildly popular in the United States as well. Photo

from Library of Congress. |

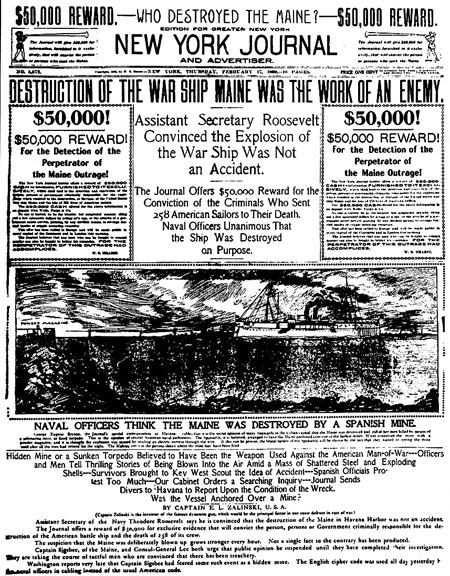

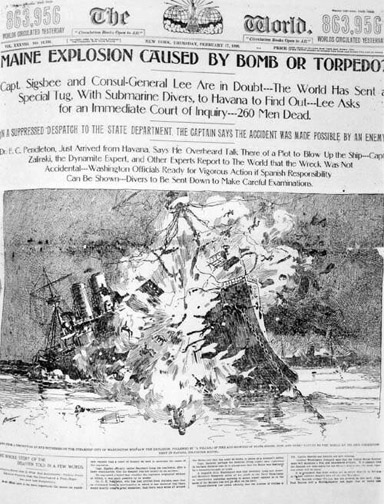

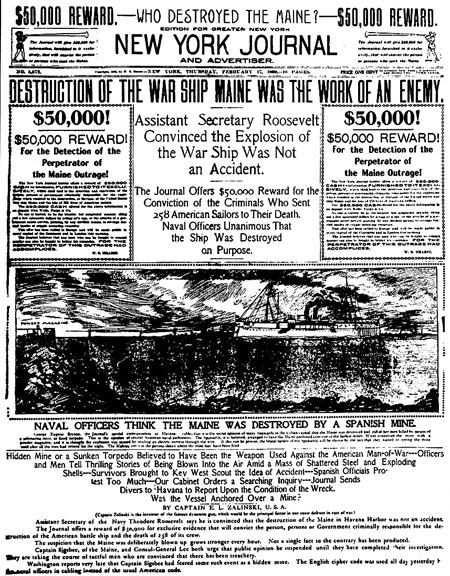

Yellow Journalism &

The Yellow Press

Yellow journalism, or the yellow press, is a type of journalism

that presents little or no legitimate well-researched news and

instead uses eye-catching headlines to sell more newspapers.

Techniques may include exaggerations of news events,

scandal-mongering, or sensationalism. By extension, the term yellow

journalism is used today as a pejorative to decry any journalism

that treats news in an unprofessional or unethical fashion

Popular opinion

in the U.S., fanned by inflammatory articles printed in the "Yellow

Press" by William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer's newspapers,

blamed Spain. The phrase, "Remember the Maine, to hell with Spain",

became a rallying cry for action, which came with the

Spanish–American War later that year. While the sinking of the Maine

was not a direct cause for action, it served as a catalyst,

accelerating the approach to a diplomatic impasse between the U.S.

and Spain. The cause of the Maine's sinking remains a subject of

speculation.

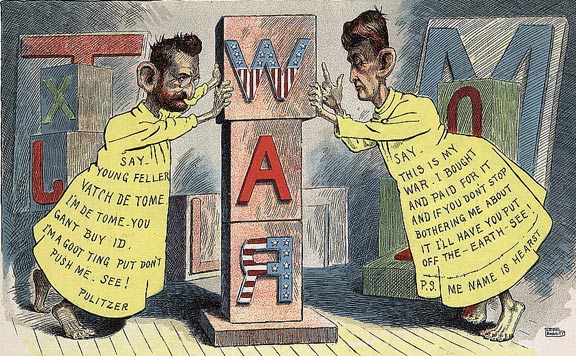

Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph

Hearst, full-length, dressed as the Yellow Kids, a satire of their

role in drumming up USA public opinion to go to war with Spain.

Most famous of the Anti-Spanish

yellow journalism was the "Olivette Incident." On February 12, 1897,

the Hearst's New York Journal reported that as the American

steamship Olivette was about to leave Havana Harbor for the United

States, it was boarded by Spanish police officers who searched three

young Cuban women, one of whom was suspected of carrying messages

from the rebels. The Journal ran the story with the headline, “Does

Our Flag Protect Women?” It was accompanied by a dramatic

sketch by Frederic Remington across one half a page showing Spanish

plainclothes men searching a nude woman. The Journal went on to

editorialize, “War is a dreadful thing, but there are things more

dreadful than even war, and one of them is dishonor.” This report

shocked the country and prompted Congressman Amos Cummings to

announce intentions to launch a congressional inquiry into the

incident.

Soon, however, the story unraveled.

Pulitzer's New York World quickly produced one of the young women

who contested the Journal’s version of the incident. Eventually the

Journal was forced to correct the story. The search had been

appropriately conducted by a police matron with no men present.

Among the most popular stories often cited as evidence of the

meddling influence of Hearst and Pulitzer is the story of

Remington's attempt to return from Cuba because there seemed to be

not much going on. As the story goes, when Remington telegraphed to

his boss to report that conditions in Cuba were not bad enough to

warrant hostilities, Hearst allegedly cabled back , "Please remain.

You furnish the pictures and I'll furnish the war." In reality,

yellow journalism probably had little influence outside of New York.

Much of the pro-war reporting came out of the American Midwest.

Authentic History - The Spanish American War

|

Captain Sigsbee on the

explosion:

It was a bursting, rending, and crashing sound or roar of immense

volume, largely metallic in its character. It was succeeded by a

metallic sound--probably of falling debris--a trembling and lurching

motion of the vessel, then an impression of subsidence (sinking of

land level), attended by an eclipse of the electric lights (the

Maine was one of the first American warships to have electric lights.)

Captain Sigsbee stumbled out of his cabin and headed for the deck.

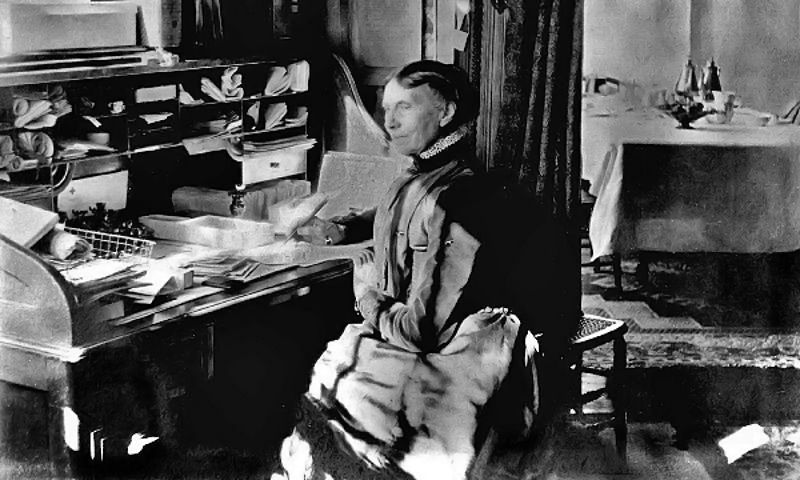

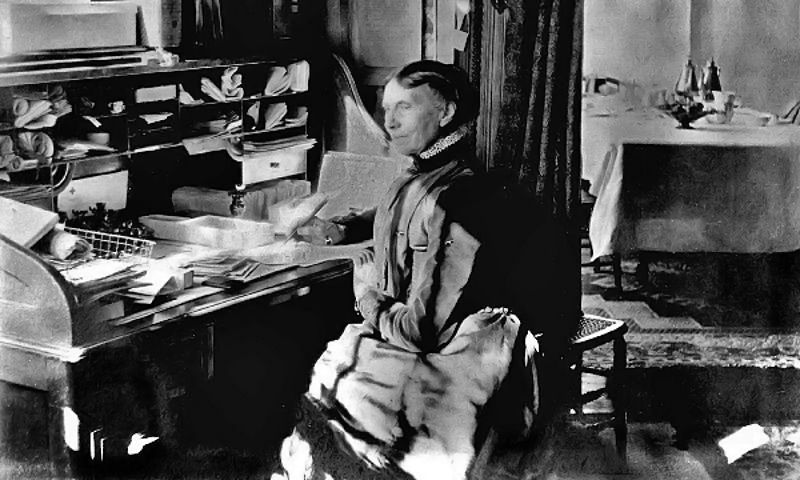

Back ashore, Clara Barton was hard at work

at her desk overlooking Havana Harbor. The 77-year old president and

founder of the American Red Cross pondered over her relief effort to bring

aid to displaced Cubans—the reconcentrados. She and a fellow American J.

K. Elwell, who was a member of the Cuban International Relief Committee,

were going over papers, expenses and receipts. These had always been

the bane of her existence; like many other high-strung and excitable

people, she was far better in the heat of a conflict than in dealing with

clerical matters.

We were busy at our writing tables until late at night. The house

had grown still; the noises on the street were dying away, when suddenly

the table shook from under our hands, the great glass door opening on to

the veranda, facing the sea, flew open; everything in the room was in

motion or out of place--the deafening roar of such a burst of thunder as

perhaps never one heard before, and off to the right, out over the bay,

the air was filled with a blaze of light, and this in turn filled with

black specks like huge specters flying in all directions. Then it

faded away. The bells rang; the whistles blew, and voices in the

street were heard for a moment; then all was quiet again. I supposed it

to be the bursting of some mammoth mortar or explosion in some magazine.

A few hours later came the terrible news of the "Maine." Mr.

Elwell was early among the wreckage, and returned to give me the news.

George

Bronson Rea, another American observer on shore that night, was a

journalist for Harper's Weekly. He had been in Cuba for almost two

years at the time. He was at a Havana cafe when he heard the mighty

blast. George

Bronson Rea, another American observer on shore that night, was a

journalist for Harper's Weekly. He had been in Cuba for almost two

years at the time. He was at a Havana cafe when he heard the mighty

blast.

Suddenly the sounds of a terrific explosion shook the city; windows were

broken, and doors were shaken from their bolts. The sky towards

the bay was lit up with an intense light, and above it all could be seen

innumerable colored lights resembling rockets.

Rea and another journalist hastened to the waterfront where they found

barricades. They told the Spaniards that they were officers of the

Maine, a lie that helped Rea and the other American to get into a boat

with the Havana chief of police. Rea described the scene:

"Great masses of twisted and bent iron plates and beams were thrown up

in confusion amidships; the bow had disappeared; the foremast and smoke

stacks had fallen; and to add to the horror and danger, the mass of

wreckage amidships was on fire. The Maine was clearly sinking, but

what happened to its crew?"

The Sinking of the USS Maine: Declaring War

Against Spain

|

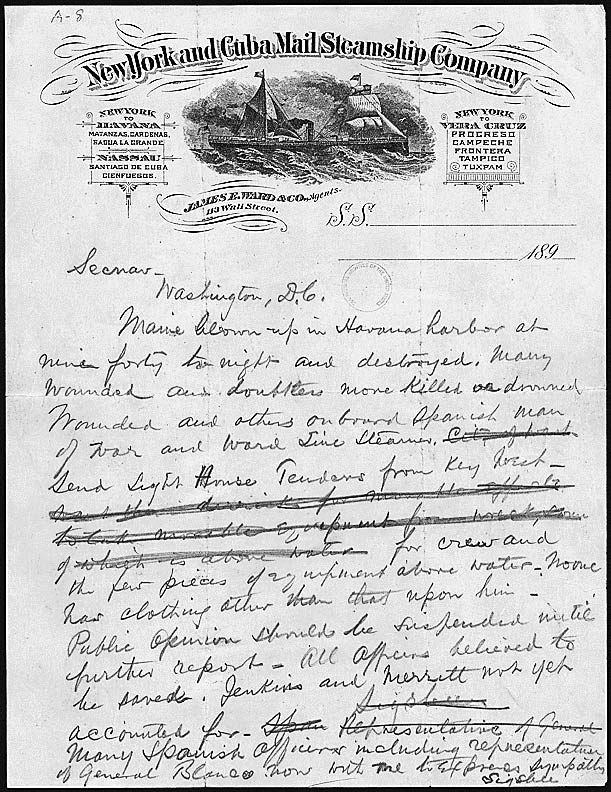

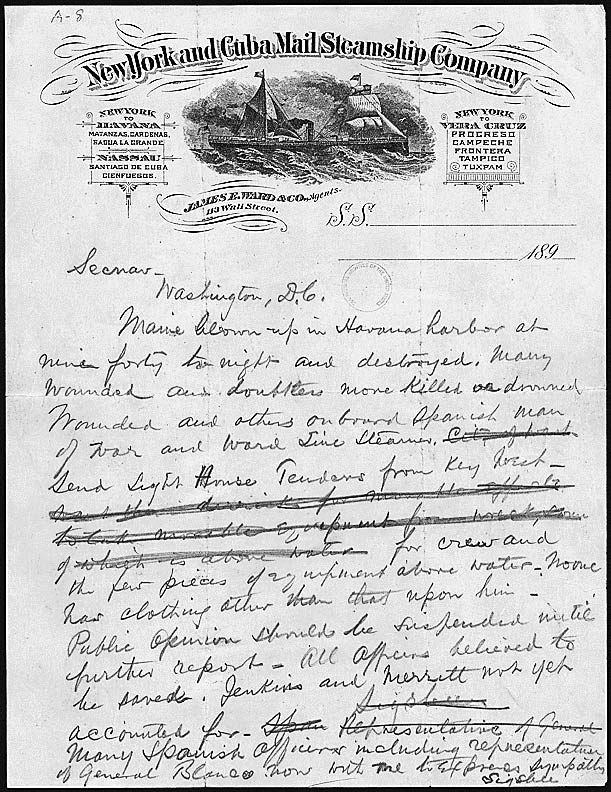

Telegram from

Captain Charles S. Sigsbee, Commander of the USS MAINE, to the

Secretary of the Navy, 02/15/1898 (National

Archives Identifier: 300266); Naval Records Collection of the

Office of Naval Records and Library, 1691 - 1945; Record Group 45;

National Archives. |

|

|

| |

Following

the explosion on the Maine, Fitzhugh Lee returned to Washington. On May

5, 1898 he was made a major general in the army and put in command of

the Seventh Army Corps. Although the unit trained thoroughly in

Jacksonville, Florida, it never saw combat. (Library of Congress -

Fitzhugh Lee)

U.S. Navy

diving crew at work on the ship's wreck, in 1898, seen from aft

looking forward. From

Naval Historic Center, Department of the Navy.

See Destruction of the Maine by Louis Fisher, The Law Library of

Congress.

"Wreck of the

U.S.S. Maine, June 16, 1911" The photograph shows the raising and salvage

operation of the ship, 13 years after it sank. After the salvage operation

was completed, the ship was resunk offshore. The image was taken by the

American Photograph Company of Havana, Cuba, and measures 34" x 9".

Photo from NARA.gov, National Archives and Records Administration.

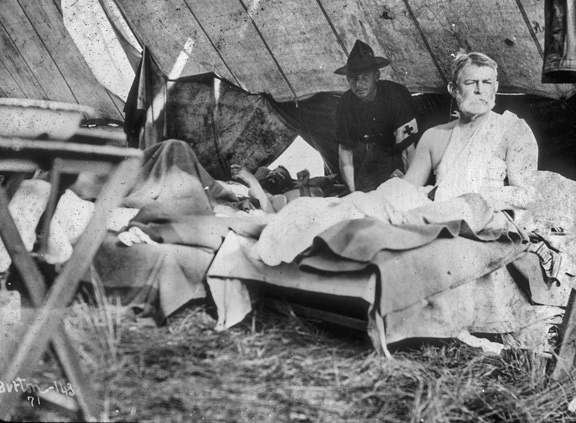

Clara tends to the wounded

Clara was late to the scene because she

thought that the great explosion had been on land, or that it had been

some sort of demonstration of military power. Although she was not present

when the Maine went down, she did reach the Spanish Military Hospital, San

Ambrosia, in time to give aid and comfort to the wounded. Most of

the officers were dining out, and thus saved. On her way from her hotel to

the hospital, she met the second-in-command officer of the Maine, who

sadly asked if she remembered her pledge of two days earlier: that she

would be available to the crew in case of disaster. She certainly

did recall, and the memory pushed her on to the Ambrosia Hospital where

she found...

"...thirty to forty wounded--bruised, cut, burned; they had been crushed

by timbers, cut by iron, scorched by fire, and blown sometimes high in

the air, sometimes driven down through the red-hot furnace room and out

into the water, senseless, to be picked up by some boat and gotten

ashore. Their wounds are all over them; heads and faces terribly

cut, internal wounds, arms, legs, feet, and hands burned to the live

flesh."

Survivors of the U.S.S. Maine explosion pose

for a picture at the Marine Hospital where Clara Barton ministered to them

on Feb. 21, 1898.

Photo from The Sinking of the U.S.S. Maine:

Declaring War Against Spain by Samuel Willard Crompton

Although she was familiar with disaster, Clara had not witnessed a scene

like this before. The Civil War wounded that she tended had experienced

bullet wounds and shrapnel from cannon fire, but not the searing flames

that come from explosions and electrical fires. Barton did what she

could for the men, sending telegrams on their behalf and staying with them

that night. Sometime during that night she sent a telegram of her

own to President William McKinley, who had urged her to go to Cuba in the

first place. Her words were simple and to the point:

"I am with the wounded."

Many Americans probably were cheered to learn that the Civil War heroine

was in action once more, tending to the wounded as she had done before.

A major poet of the day took her brief five-word telegram and converted it

into a song that newspapers reprinted from coast to coast:

"I am with the wounded," flashed across the wire

From the Isle of Cuba, swept with sword and fire.

Angel sweet of mercy, may your cross of red

Cheer the wounded living; bless the wounded dead.

"I am with the starving," let the message run

From this stricken island, when this task is done;

Food and plenty wait at your command,

Give in generous measure; fill each outstretched hand.

"I am with the happy," this we long to hear

From the Isle of Cuba, trembling now in fear;

Make this great disaster touch the hearts of men,

And, in God's great mercy, bring back peace again.

If there was going to be

war, it would be a new type of war. Americans, however, were

thrilled to learn of the continuity Clara Barton would provide between the

Civil War and what might now become the Spanish-American-Cuban War.

77-year-old Clara Barton had proved her worth once more.

The Sinking of the U.S.S. Maine: Declaring War Against Spain by Samuel

Willard Crompton

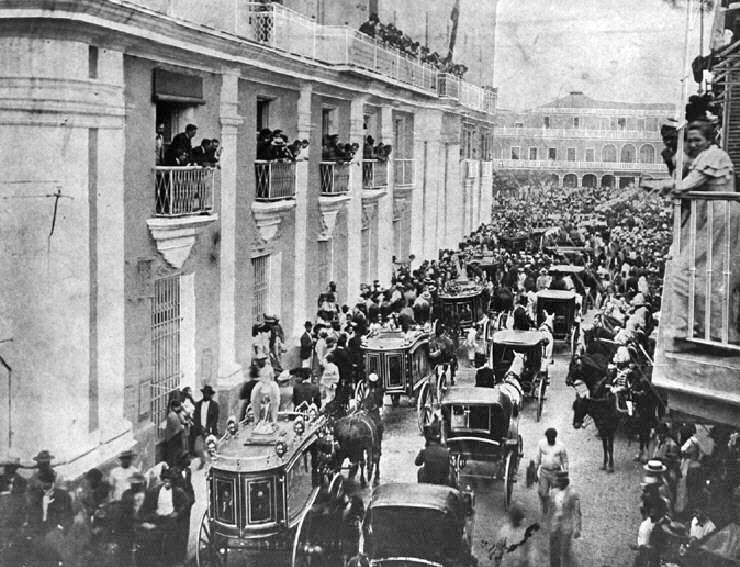

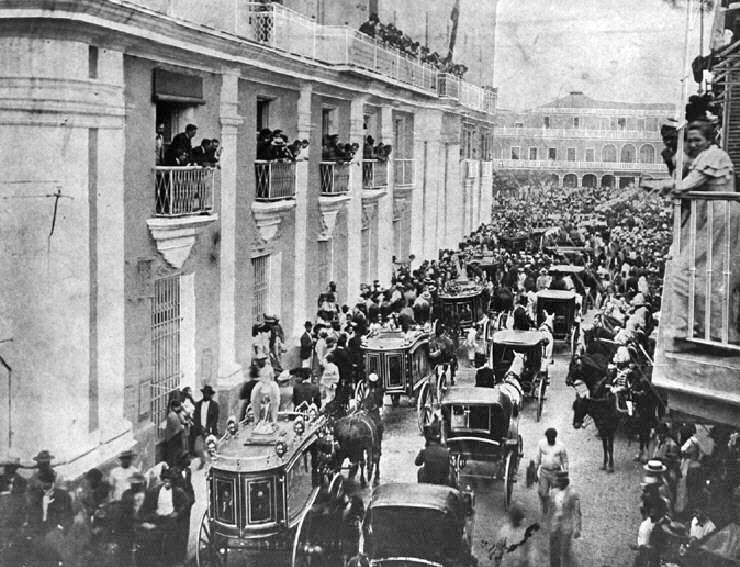

15 February 1898. Funeral

procession in the streets of Havana, Cuba, for crewmen killed when the

Maine exploded. Retouched halftone photograph, copied from Uncle Sam's

Navy, Volume IV, Number 3, 19 April 1898. U.S. Naval Historical Center

Photograph.

From Naval Historic Center, Department of the Navy.

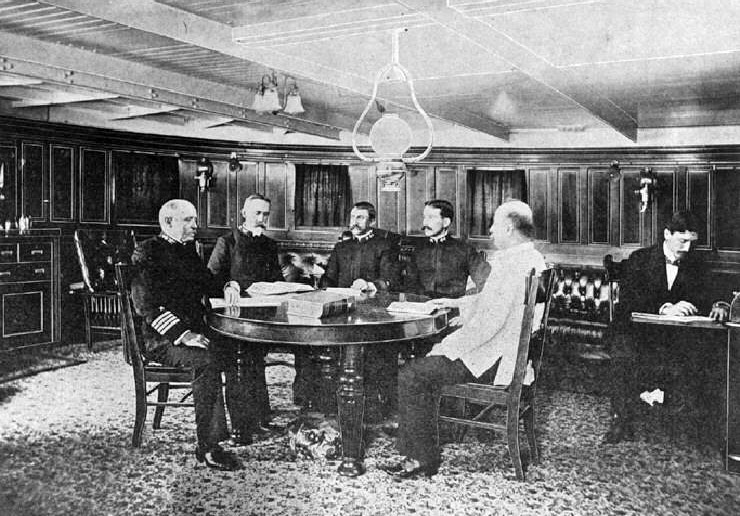

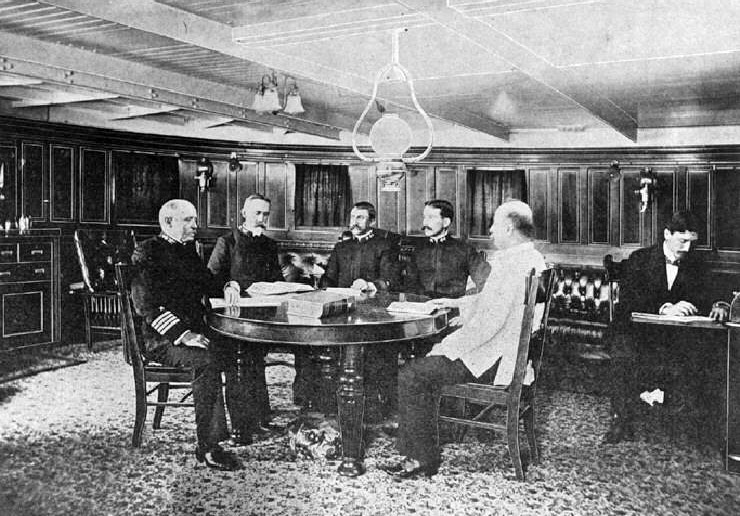

Members of the Navy Court

of Inquiry examining Ensign Wilfrid V. Powelson, on board the U.S.

Lighthouse Tender Mangrove, in Havana Harbor, Cuba, circa March 1898.

Those seated around the table include (from left to right): Captain

French E. Chadwick, Captain William T. Sampson, Lieutenant Commander

William P. Potter, Ensign W.V. Powelson, Lieutenant Commander Adolph

Marix. Photograph copied from Uncle Sam's Navy, 12 April 1898.

Tampa

reacts to the news of the Maine explosion; H.B. Plant exerts his influence

|

|

|

Tampa

Mayor Myron E. Gillett

Term: June 5, 1896- June 5, 1898

Photo from "Men of the South" (where his and his son's photos

are displayed in incorrect order to the caption) |

After the explosion on the

Maine, Tampa's mayor and congressman promptly petitioned Secretary of War

Russell Alger for protection against the Spanish Navy. Leading

citizens and the Board of Trade demanded a military presence and the

funding of coastal defense sites. But from the armchair generals in

Washington, there was no response. Then on March 22nd, Henry Plant

wrote Secretary Alger personally, calling attention to his multi-million

dollar investment in Port Tampa. On March 25th, Alger sent his Chief

of Engineers to begin fortifications on Egmont and Mullet Keys.

With that,

Florida, Tampa and H.B. Plant were in the still-undeclared war. The

Olivette had already made one run for Assistant Secretary of the Navy,

Theodore Roosevelt, delivering ammunition to Key West. Local papers began

boosting Tampa as the obvious supply point for operations in the

Caribbean. At the end of March, a real-life seagoing admiral checked

into the Port Tampa Inn. On behalf of the Plant System, Henry

Plant's second in command, Franklin Q. Brown, gave "Fighting Bob" Evans a

tour of the harbor. The admiral passed the word to the press corps.

In the event of war, make way for the Navy! Fifty thousand troops

would be embarked from Port Tampa.

From Henry Plant - Pioneer Empire Builder

Clara continues her relief work

Amid the speculation of the cause of the Maine’s blast, Barton continued

with her relief effort. She traveled on to the small towns and

villages where she found deplorable conditions. Calling for a battle

against the “enemies,” of “dirt and filth,” Barton rallied for volunteers

to thoroughly clean and whitewash a hospital, for example. Once enlarged,

a freshly supplied hospital could accommodate more patients. Local

physicians anguished by lack of resources, spurred to action with Red

Cross support.

Clara kept the public alerted

to the progress of the Red Cross relief effort. Highlighting its humanity

and neutrality, she reported about her cooperation with the Spanish

authorities. Spain was one of the original founders of the International

Red Cross and Barton fostered a rapport with General Ramón Blanco y

Erenas. She reported that, “General Blanco was glad of this relief

and sorry for the condition of the people.” She explained that her

cooperation with the Spaniards was through the international recognition

that the Red Cross operated as a neutral humanitarian body.

Clara disregarded any gender

inequality. Rather, she met the Spaniards on equal terms. “I meet you

gentlemen not as an American and you as Spaniards but as the head of the

Red Cross of one country greeting the Red Cross men of another,” she

affirmed. “I do not come to speak for America as an American, but from the

Red Cross for humanity.” Throughout her stay, she noted that General

Blanco and his staff’s unfailing “kindly spirit” prevailed. She

wrote, “I was begged not to leave the island through fear of them.” They

promised to extend “every protection in their power” to the Red Cross.

The Spanish American War

Centennial

Stephen

Barton correspondence May 1883 - Jan 1901

Clara's No.

2

Journal on Cuba

Journal images from the Library of Congress collection of Clara Barton

scrapbooks, journals and diaries |

The journal numbered "2" with Clara's notes on Cuba at the Library

of Congress picks up when she has been there for about two weeks;

she wrote in "The Red Cross in Peace and War" that she arrived on

Feb. 9th. Her entries in her No. 2 journal cover

Feb. 26, 1898 to July 1, 1898.

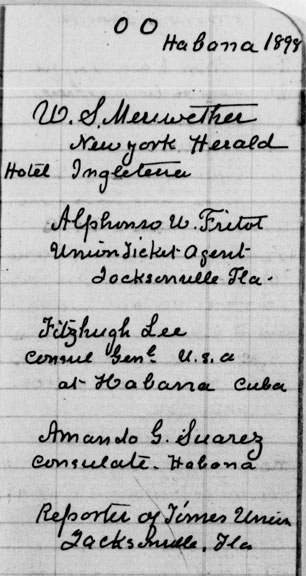

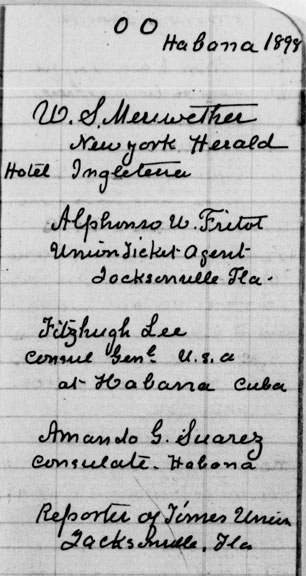

Clara records addresses of persons she met on the way to and in Cuba

1898.

On page marked 00, names of correspondents, reporters, etc.

She

then records Mr. & Mrs. Plant of Plant System, Tampa, Fla.

Afterward she records several names of persons from the northeast,

and then Mrs. Scovill on boat from Tampa to Cuba. She

then names people she met in Key West, and then Havana.

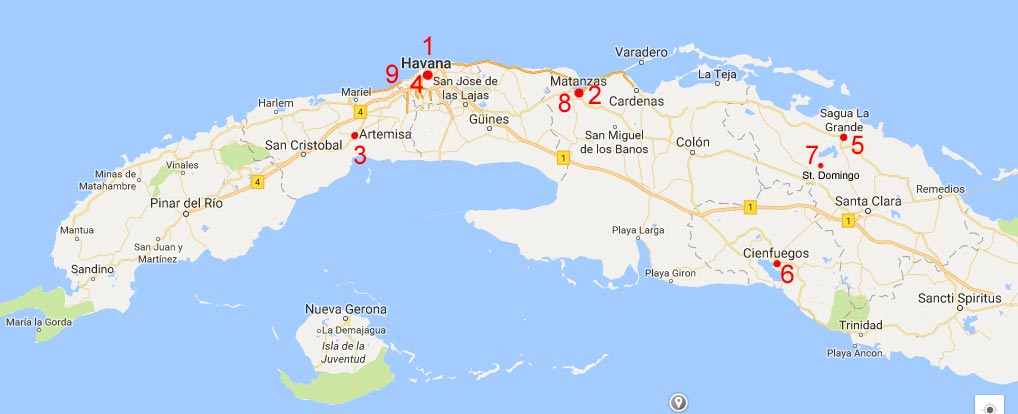

In Cuba,

on Saturday, Feb. 26 she records her first dated journal entry:

Staff arrived. Warehouse and on the 27th, Cleaned hospital.

Successive dates document her travels and relief work from town to

town in Cuba. All are brief entries with short statements as

to what was done and who she encountered.

.jpg)

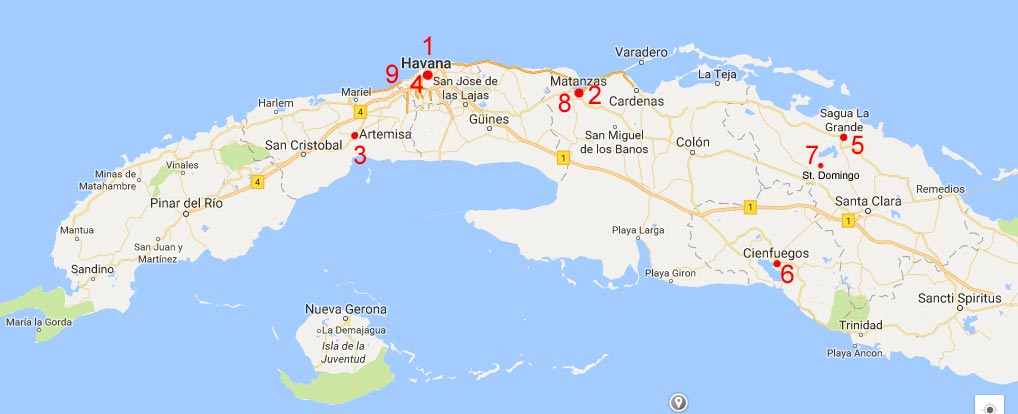

Within

a span of 9 days, she travels from Havana to Matanzas, Artemisa,

back "home" to Havana, Sagua La Grande, Cienfuegos, Santo Domingo,

back to Matanzas and back to Havana.

Her

comments on General Blanco above were referring to her visit

recorded in her journal on Tuesday, March 17 "At 10am went to

call on Gen. Blanco." |

|

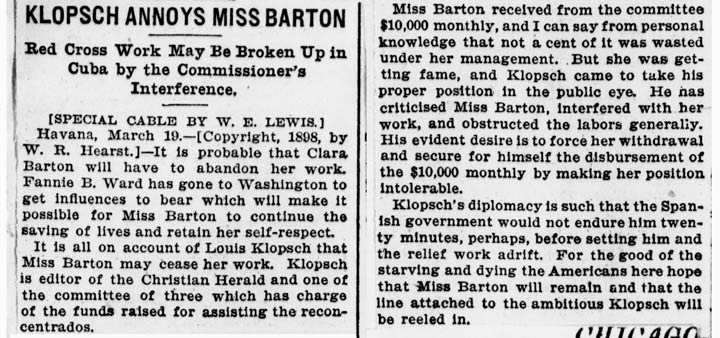

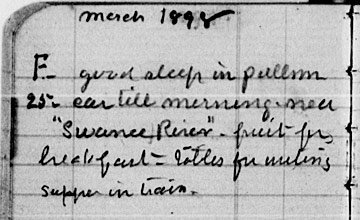

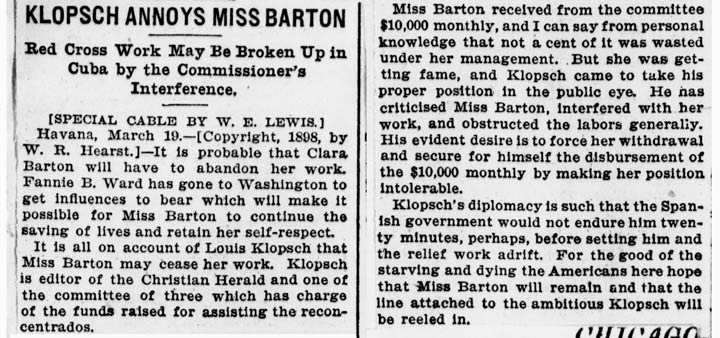

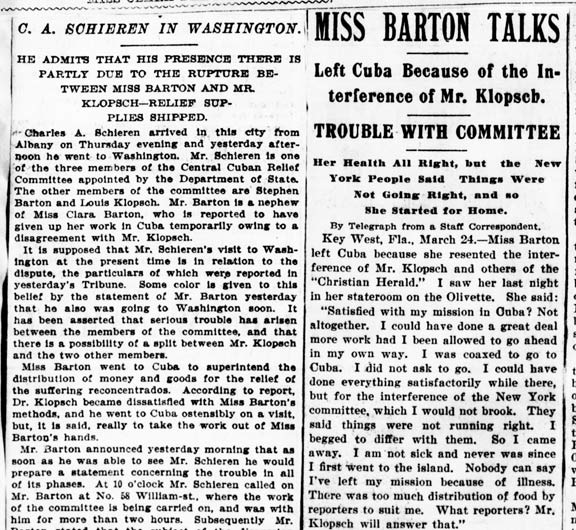

Apparently, some friction

developed between Barton and Louis Klopsch, editor of the Christian

Herald, over stories he was printing about the Red Cross' problems

in Cuba. March 19, 1898. |

|

Newspaper clippings from the Library of Congress collection of Clara

Barton scrapbooks, journals and diaries

Tuesday, March 22, 1898

Decided to go home to take Egan & Cotrell. Mr. Sexton came from

Matanzas. Got ready for Archbishop at Havana, did not come. Decided

to go to Washington, Egan & Cotrell, packed, drew checks, saw Consul

(Fitzhugh) Lee.

Clara departs Cuba

Wed., March 23, 1898

Archbishop came, blessed the hospital. Started for Washington --

boat -- Cotrell can't go - Off -- seaside to Key West, arr 9+

night--letter, got up, saw reporters. Went on to Port Tampa,

pleasant sail till next day.

The article

below, dated March 24, Key West, indicates Clara was interviewed in her

stateroom on the Olivette on the night of the 23rd.

Newspaper stories on reasons why Clara left Cuba

|

Clara arrives in Port Tampa

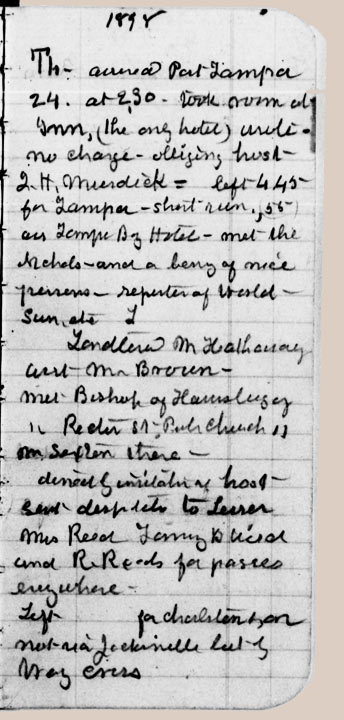

Journal images from the Library of Congress collection of Clara

Barton scrapbooks, journals and diaries

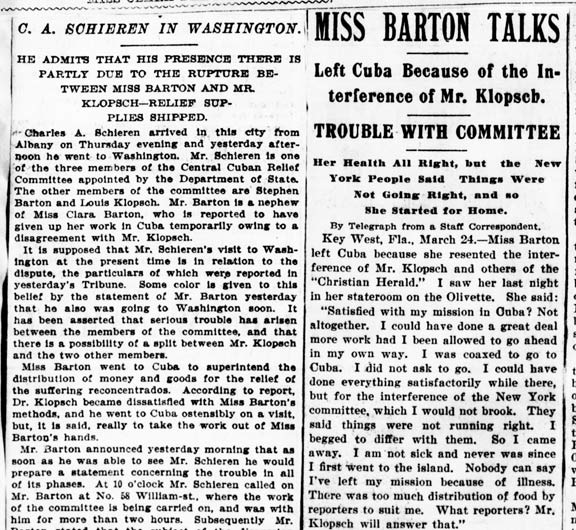

Thu, March 24, 1898

Arrived Port Tampa at 2:30 - took room at Inn (the only hotel),

wrote, no charge - obliging hush - Q.H. Murdick - left 4:45 for

Tampa - short run, (55) arr Tampa Bay Hotel - met the Nichols - and

a bevy of nice persons - reporter of World - Sun, etc.

[Illegible] M Hathaway, met Mr. Brown, met Bishop of Harrisburg,

met Rector St. Paul church - M Sexton there - dined by invitation of

host - sent desk sets (?) to Lesser - Mrs. Reed

[illegible] and R Reeds for passes everywhere. Left for

Charleston on next - via Jacksonville [illegible].

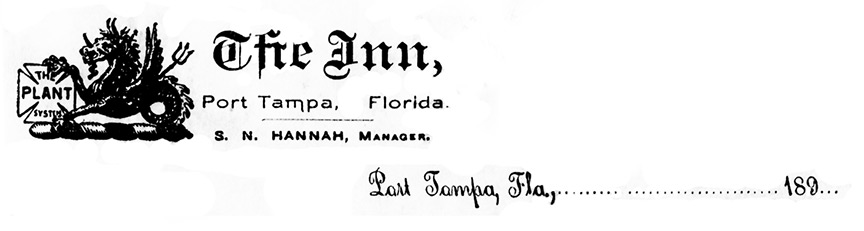

Clara's

reference to the "Inn" and in parenthesis "the only hotel" indicates

she took a room at H. B. Plant's Port Tampa Inn, did some writing,

and her notation "no charge -- obliging hush - Q.H. Murdick." would

seem to indicate the name of the desk clerk and that he allowed her to

stay for free because she was only there for 2 hours and 15 minutes,

having left for Tampa at 4:45 pm (which would explain why she

wasn't charged for the room.)

Back then,

Port Tampa was a separate town from the city of Tampa. An H.B. Plant

railroad connected the two, with the Tampa end being at the Tampa Bay

Hotel. Clara took this train to the Tampa Bay Hotel where she met

various people. She had dinner by invitation, and left for

Charleston on the next train via Jacksonville. No notation was made

of staying overnight at the Tampa Bay Hotel. In fact, her journal

entry for the next day indicates she spent the night on a train from Tampa

to Washington DC.

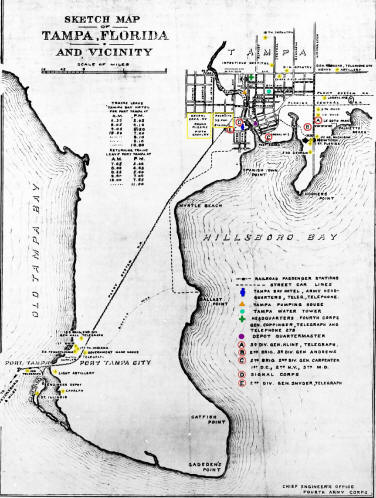

This

1898 map of Tampa shows the Spanish American War camps with Port

Tampa at lower left and Tampa at upper right.

Click map to open in new window, then click again to enlarge.

|

|

|

The Port Tampa

Inn on the left, the St. Elmo on the right, 1900.

Photo from Shorpy, Detroit Publishing Co.

The Tampa Bay

Hotel was not Plant's first hotel in the area. In 1889, he

opened the Port Tampa Inn near his newly opened shipping piers

and port on the shores of Tampa Bay. Perhaps the most

interesting feature of the Port Tampa Inn was that hotel

guests could fish from their rooms — the hotel was built on

stilts over the bay — and the kitchen staff would prepare

their catch and serve it to them in the dining room. Tampa

residents would have preferred that Plant build a port on the

Hillsborough River, but dredging a ship channel in

Hillsborough Bay was prohibitively expensive. Old Tampa Bay

had a natural deepwater channel and Plant decided to build his

"Port Tampa" on the west side of the Interbay Peninsula. Upon

completion of the rail extension to Port Tampa, Plant built a

wharf, warehouses, and a resort called Picnic Island. Port

Tampa City received a state charter in 1885, a direct result

of Plant's port facility. After the city completed a bridge

across the Hillsborough River at Lafayette Street (now Kennedy

Blvd), Plant began construction of the Tampa Bay Hotel. He no

doubt wanted to outdo the efforts of his friendly rival, Henry

Flagler, who had just finished the $2 million Ponce de León

Hotel at St. Augustine.

(From "Grand Hotels" by Rodney Kite-Powell, Tampa Bay History

Museum) |

Other wartime notables who

passed through Port Tampa included Teddy Roosevelt and the Rough Riders,

the Buffalo Soldiers, Richard Harding Davis, Stephen Crane, and Frederic

Remington. Port Tampa became less important when several dredging projects

made the Port of Tampa accessible to all shipping.

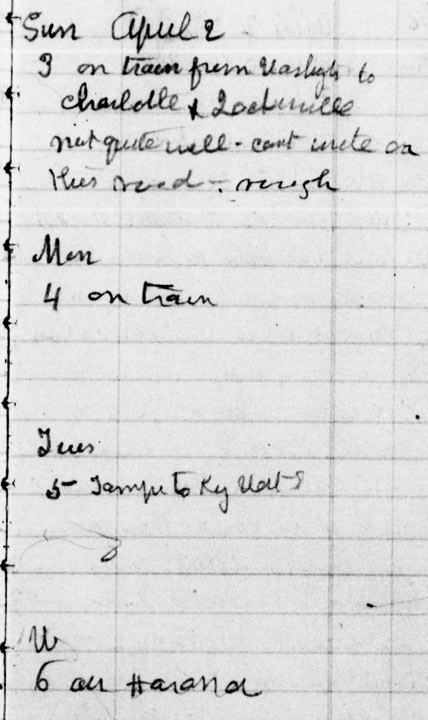

March 26 through April 2 --Washington DC - Clara

makes notations for her various dealings with the State Dept. and

other Red Cross business dealings.

Clara

heads back to Cuba

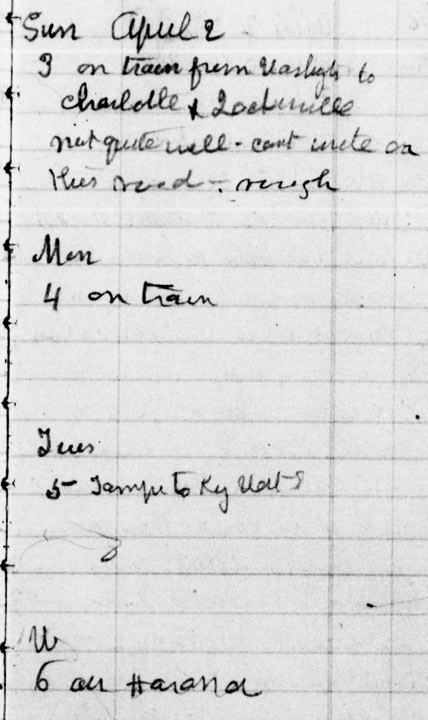

Sunday, April 3 - Clara is on a train from Washington to

Charlotte, then Jacksonville.

Monday, April 4 - On train is all she records

Tuesday, April 5 - Only writes Tampa to Key West

Wednesday, April 6 - On Havana (a steamer.)

|

|

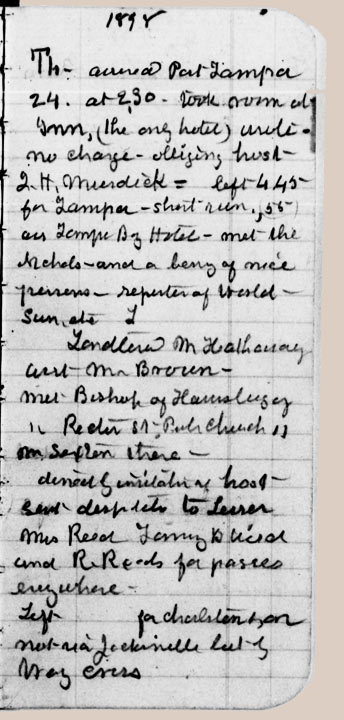

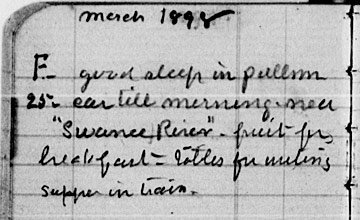

Friday, March 25, 1898

Good sleep in Pullman car till morning, near Suwannee River, fruit

for breakfast..

|

|

The Inn at Port Tampa, guest note paper image from Red Cross

Correspondence file, Spanish American War - Cottrell

|

|

Close

up of previous photo, Port Tampa Inn,

from Shorpy Close

up of previous photo, Port Tampa Inn,

from Shorpy

Port Tampa and Port Tampa City, located to the west of present-day

MacDill Air Force Base, were established in the late 1880s, and for a

number of years Port Tampa was the natural deepwater port for Tampa. Then,

in the early 1900s the port was dredged at the mouth of the Hillsborough

River in downtown Tampa, and most of the port business moved there.

(Starting in 1904 the Federal government, in part, funded the dredging of

the channels in Tampa and Tampa Bay, opening it up again to be a

significant port. Tampa quickly rebounded and boomed. In 1909, the channel

up the Hillsborough River was deepened to 12 feet from Tampa Bay to Jean

Street Shipyard.) Today, the port at Port Tampa City is still in operation

but on a much smaller scale than that at the bustling Port of Tampa. The

two ports are about ten miles apart.

At right, close up of the

St. Elmo Inn, from

Exploring Florida

Clara

is back in Cuba

Thurs., April 7 -

First day back, trunks came up, strong talk of

war. Clara mentions concern by authorities for her safety, "the

lawless element, the mob, the rioters" but one official says he would take

her to his home to protect her with his life.

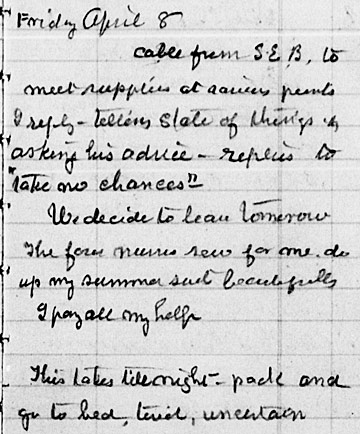

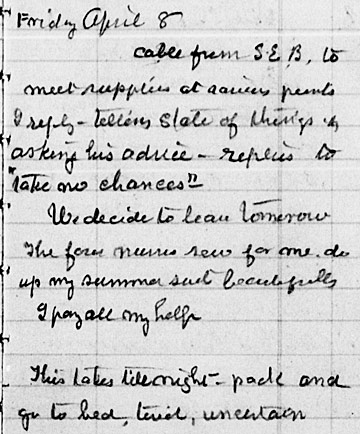

Friday, April 8 - Clara sends a telegram to her nephew, S. E.

Barton, telling him of the state of affairs in Cuba and asks his advice.

He replies to "take no chances."

We decide to leave tomorrow. The four nurses sew for me, do up my

summer suit beautifully. I pay all my help. This takes all

night, pack and go to bed, tired, uncertain.

|

Declaration of War forces Clara to leave Cuba; sets up

Red Cross headquarters in Tampa

Due to the coming war, the

order was given for all American citizens to leave Havana. Clara was

forced to abandon her relief work and she accepted Blanco’s farewell and

blessing and in her words, she left those “poor, dying wretches to their

fate.” One newspaper reported, “The whole system of caring for and

giving aid to the starving Cubans is for the time being brought to a

complete standstill.”

On April 9th, she packed her bags and headed to Tampa, where she set up

the American Red Cross headquarters.

In her book, The Red Cross

in Peace and War, Clara wrote:

Having made the best possible arrangement for the maintenance of the

institutions we had brought into being and had fostered in Havana; and

with the saddest regrets that we should have to abandon a work so well

begun, we boarded the ship “Olivette” on April 11th*

[9th], and started for the United States. After a great deal of

discomfort, caused by the overcrowding of passengers and the heavy seas,

we reached Tampa, Fla., on April 13th*

[11th].

After a day or two of rest, Miss Barton proceeded to Washington with

Drs. Hubbell and Egan, the remainder of the party stopping in Tampa.

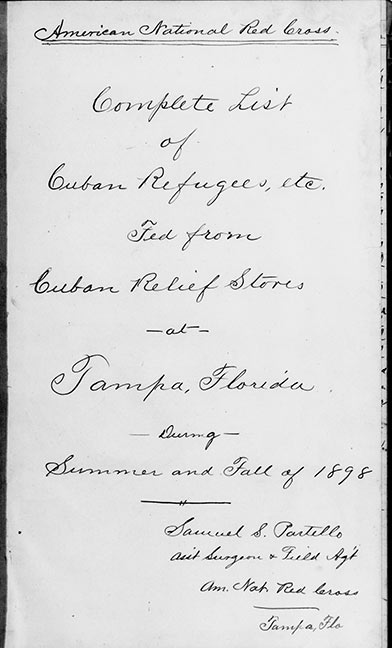

There were at that time

probably about fifteen hundred Cuban refugees in Tampa and eight or nine

hundred in Key West, who were entirely dependent. The Red Cross took

upon itself the task of maintaining these poor people, and for a period

of seven months its agents provided for them. It should be said,

however, that the citizens of both these cities appointed committees and

did all they could to relieve the necessities of these large bodies of

indigent people.

*Clara

wrote incorrect dates of April 11 and April 13. The dates were

actually April 9 and April 11 as indicated in Clara's journal. In another

of her books, The Red Cross, a History of.., she wrote:

And the ninth of April saw us again on ship board, a party of twenty,

bound for Tampa. We would not, however, go beyond, but made headquarters

there, remaining within easy call of any need there might be for us.

|

|

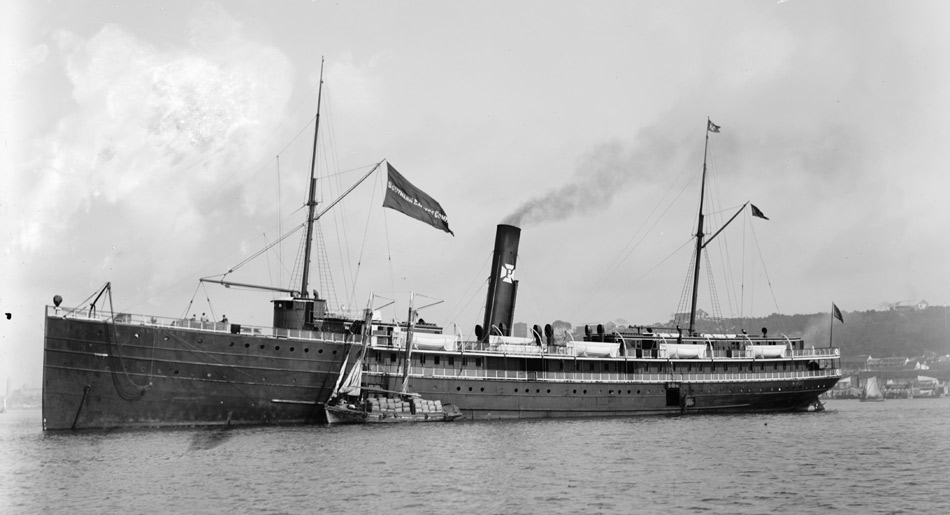

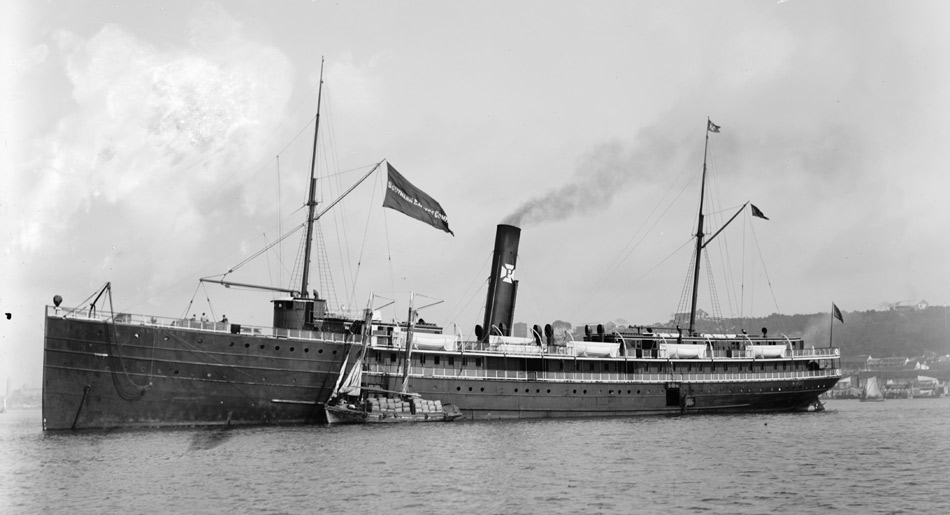

The

Olivette in Havana harbor, circa 1880-1901. It was the

second steamer used by the H. B. Plant System and made regular runs

between Tampa, Key West and Cuba. It joined his first steamer

on these runs, the Mascotte, a smaller steamship. Both were

named after comic operas by

Achille Edmond Audran (1840-1901), a French composer best known

for several internationally successful operettas, including

Les Noces d'Olivette (1879),

La Mascotte (1880), Gillette de Narbonne (1882), La Cigale

et la Fourmi (1886), Miss Helyett (1890) and La Poupée (1896).

Photo from Library of Congress

Close up

of flag showing "Southern Express Company"

|

Clara

arrives in Tampa and stays at the Arno one night, then the Towne residence in Hyde

Park

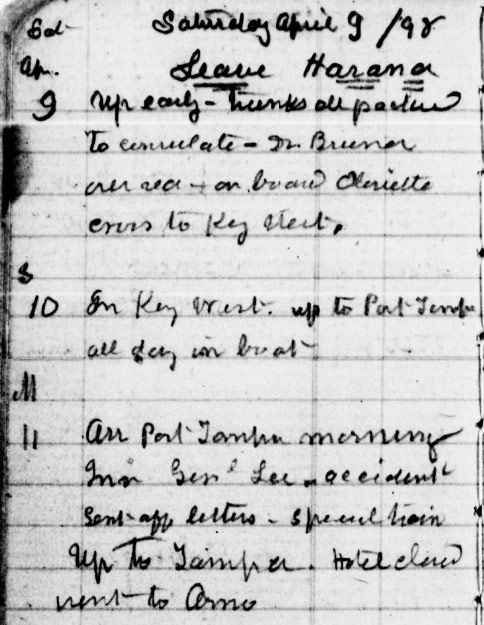

April 9, 1898 - April

11: Havana to Key West to Tampa - Clara was up early on

April 9, 1898 to pack her trunks and head to the consulate, Dr. Bruner.

She left Havana onboard the Olivette and arrived in Key West on April 10.

From Key West she sailed all day to Port Tampa where she arrived in the

morning on April 11. There she met Gen. Lee by accident, sent

off some letters, and took a train into Tampa. She made a notation

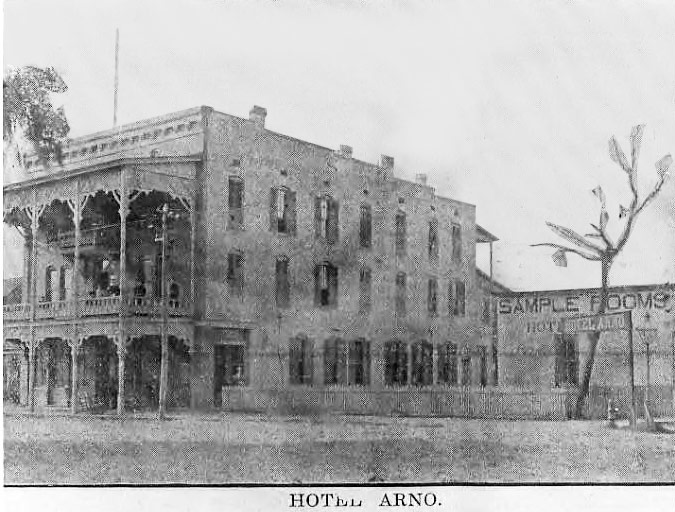

"Hotel closed" which may refer to the Tampa Bay Hotel. Then she notes

"went to Arno."

|

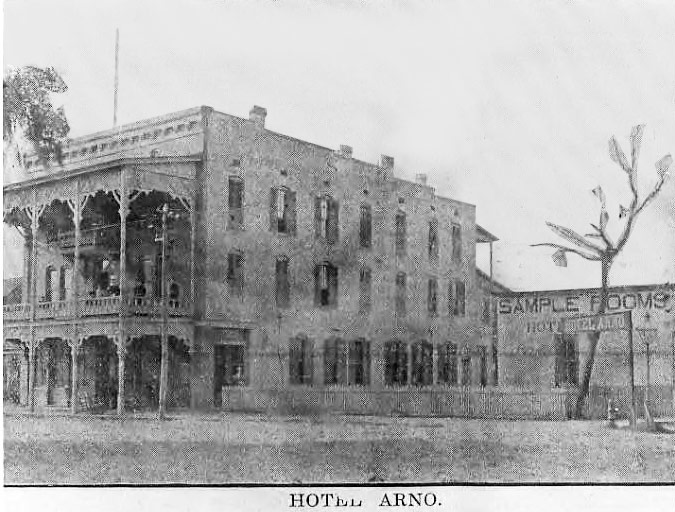

| Hotel Arno at 508-510

Tampa Street, circa 1900.

Burgert Bros. photo is a photo of a newspaper photo, courtesy of

the Tampa-Hillsborough County Public Library.

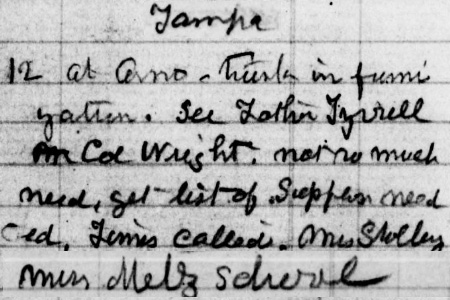

On April 12 at

the Arno, her trunks were in fumigation. She saw Father Tyrell

and Col. Wright. "Not much need, get list of supplies needed."

"Times called" may be a reference to a reporter stopping by.

She mentions a Mrs. Shelly and Miss Metz's school. |

Two styles of Hotel Arno guest paper, image from Red Cross Correspondence

file, Spanish American War - Cottrell

Fumigation was a method used in the

19th century to disinfect clothing and cargo. It was usually used

for immigrants and passengers arriving from foreign countries.

Clothing was placed in an apparatus that produced a partial vacuum, then

superheated steam was introduced, fully disinfecting the clothing.

Afterward, a partial vacuum was recreated to quickly dry the clothes.

The process was often destructive, damaging clothing and goods.

Some steamship lines fumigated passengers' baggage with sulfur fumes for

no less than 6 hours.

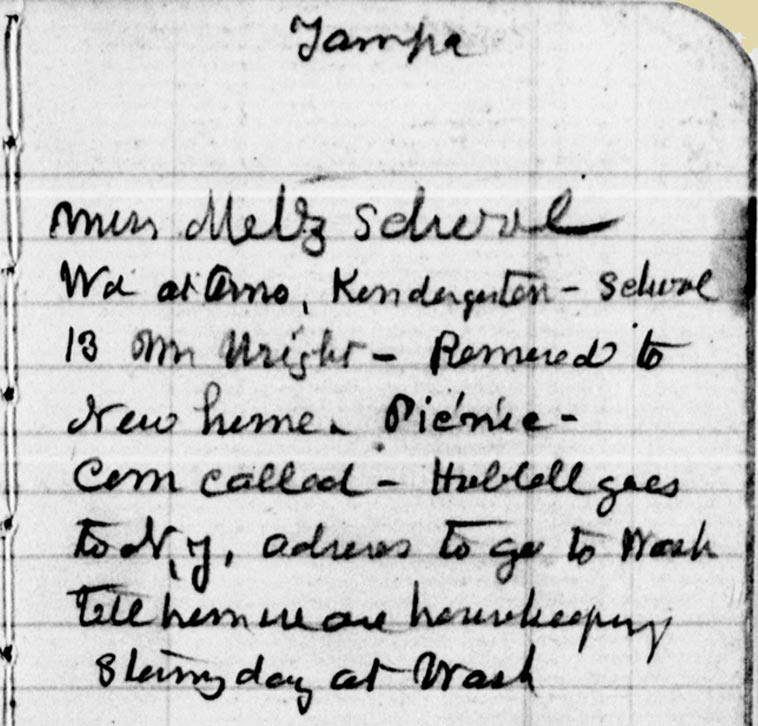

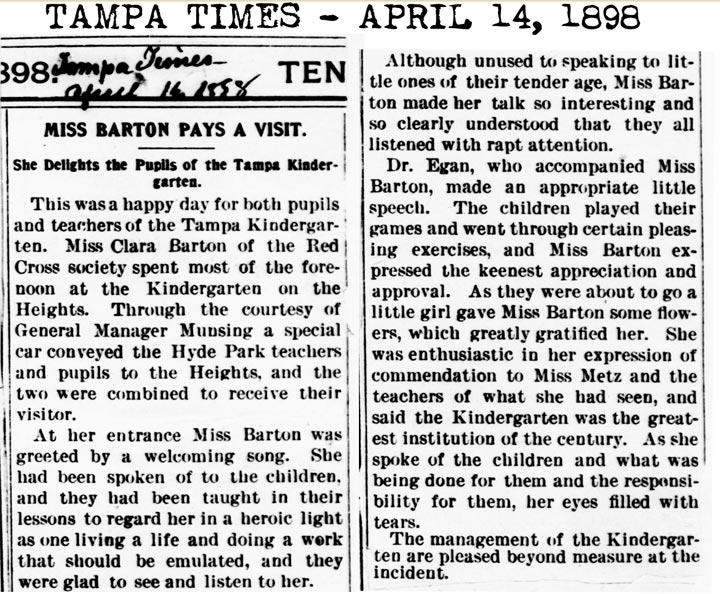

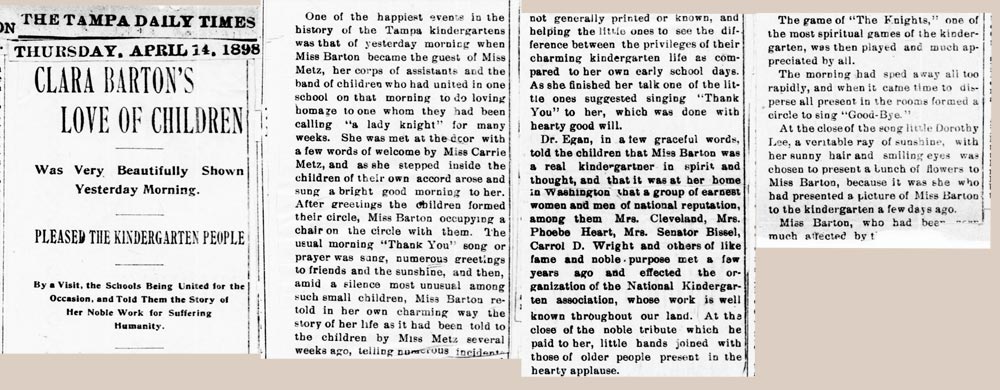

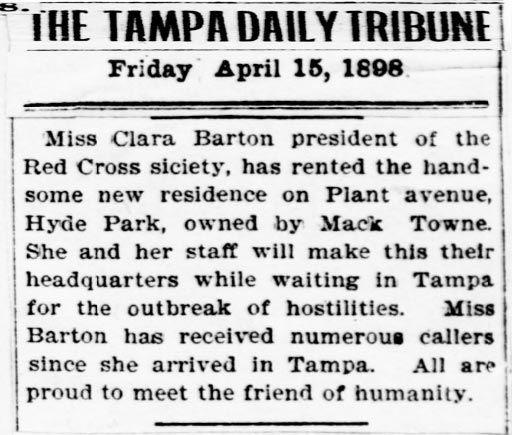

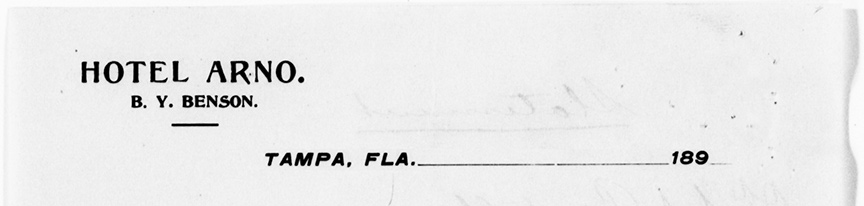

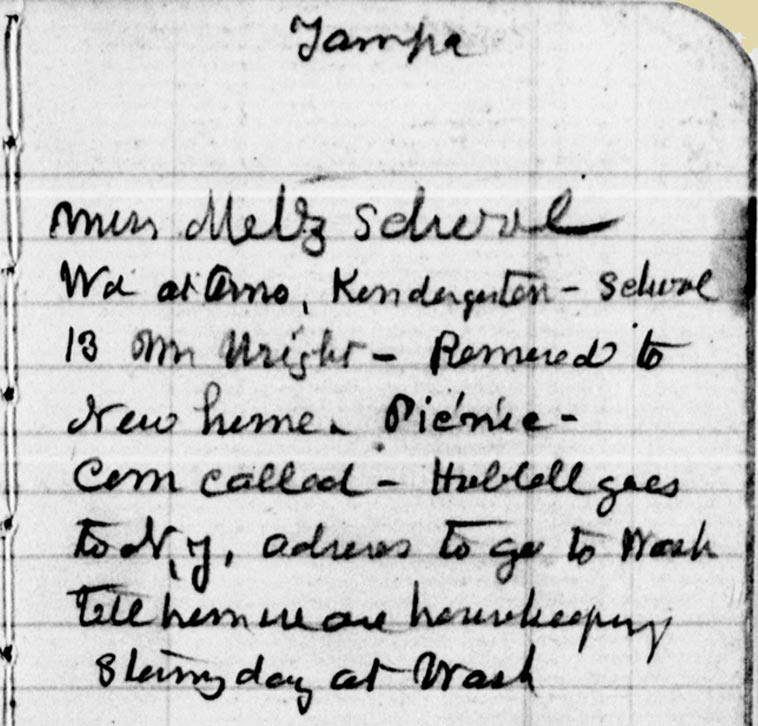

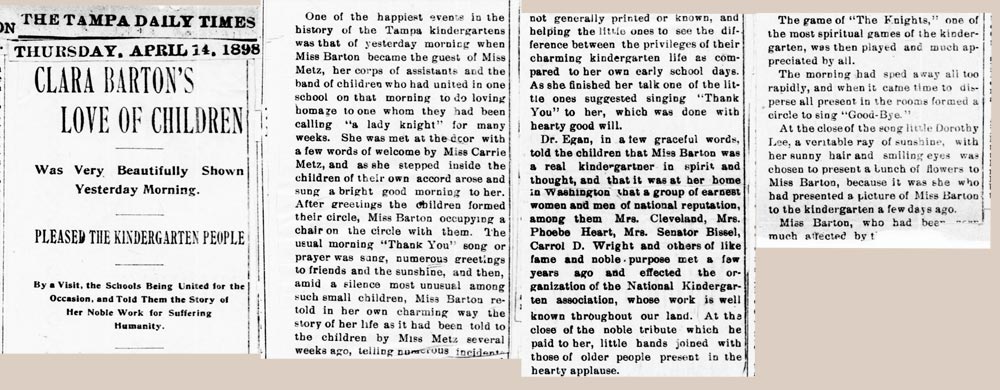

On Wed.

April 13,

at the Arno, Clara mentioned Mrs. Metz school and a kindergarten.

The next day, the Tampa Tribune had a story about Clara's visit to

the kindergarten in Tampa Heights.

|

She met with Mr. Wright

and "removed to a new home" (a reference to leaving the Arno and

staying at the home of J. Mack Towne in Hyde Park. See April 14th.)

She also mentions a picnic (the one shown below) and "Com called -

Hubbell goes to NY, advises to go to Wash. Tell him we are

housekeeping (probably a reference to getting the Red Cross affairs

organized and situated), stormy day at Wash. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

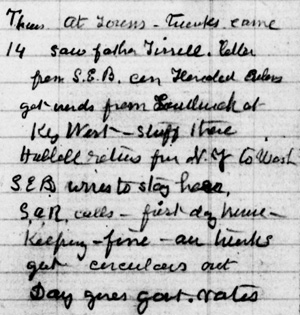

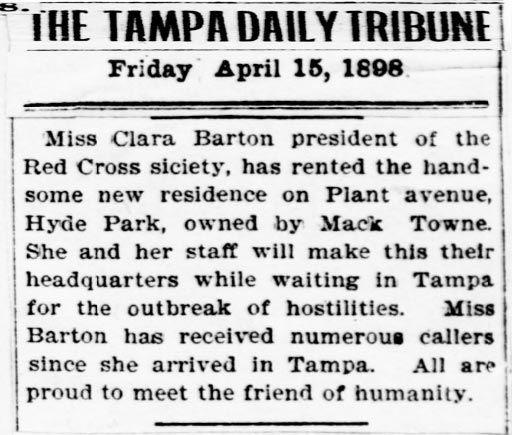

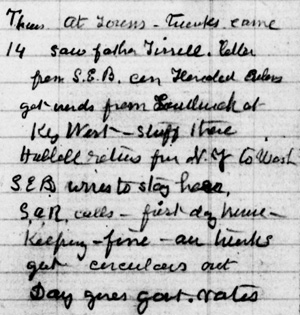

On Thursday,

April 14,

Clara wrote that she is "at Towns" (the home of J. Mack Towne at 350

Plant Avenue) and her trunks have arrived. "S.E.B. wires to

stay here" is a reference to her nephew, Stephen E. Barton, a son of

her brother David Barton & his wife Julia. Stephen was 2nd

V.P. of the American Red Cross and Chairman of The Central Cuban

Relief Committee.

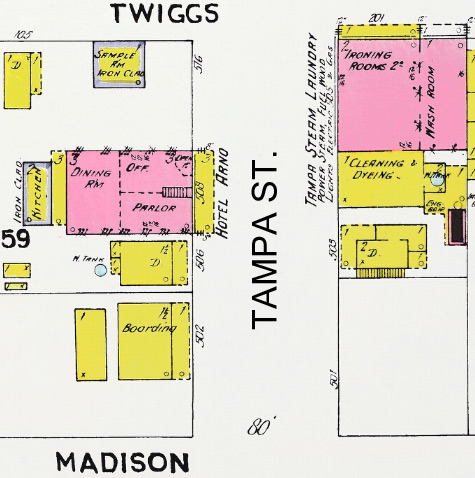

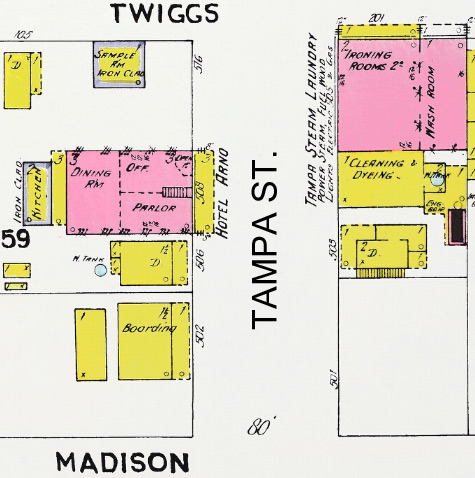

The 1903 Sanborn fire insurance map from the UF

digital map collection shows the Arno was located across Tampa St.

from Townes' Tampa Steam Laundry. This is probably how she

came to be invited to stay at the Towne's home.

Zoomable view of Clara's journal from April 9 though April 14,

1898

|

|

Below: Towne's Tampa Steam

Laundry as seen from the intersection of Tampa St (right) and Twiggs

(left.)

Photo from "Tampa

Illustrated" at Internet Archive, compiled and published by C.

E. Bissell and Roy Dougherty in 1903. Photo by Fred Barker.

The 1903 Sanborn map below shows the vantage point from which the

above photo was taken.

Not only is this the location of NY

Pizza, it appears to be the same building.

|

|

Clara

Barton Picnicking in Tampa

|

By Hampton Dunn:

This rare photograph was made in 1898 by Mrs. E. B. Drumright (then

Miss Annie Laurie Dean) and is one of the few known portraits of

Miss Barton of this era. Miss Barton (striped neckpiece) is seated

to the right of the coffee urn. The other women are not

identified, but the men are (left to right) Mr. McDowell, Dr.

Egan, and Dr. Elwell. Miss Barton at first was stationed in

the plush hotel, but moved to more modest quarters over on Plant

Avenue.**

**As

indicated by her journal entry, Clara stayed at the Arno, not at the

Tampa Bay Hotel. Barton was extremely frugal with Red

Cross's funds and unless she was given a room for free (which is

highly doubtful H. B. Plant would have done) she would have never

stayed at the TBH. She moved into the J. Mack Townes home the next

day. |

Clara

Barton, founder of the American Red Cross, picnicking at the

Hillsborough River's edge on the grounds of the Tampa Bay Hotel.

Recorded in her journal as April 13, 1898.

The photo above was part of Hampton Dunn's

personal collection in 1982 and at the time was only one of two

known in existence. The other was in the Smithsonian in

Washington DC. Dunn was honored by the University of South

Florida in 1982 at which time he donated the bulk of his

approximately 30-year collection to the university, including this

photo. |

|

Clara

in Tampa, urged to go to Washington DC

|

|

Clara spent Friday, April 15, 1898

writing a letters and sending 2 telegrams to her nephew, Stephen E.

Barton. It was "another windy day." She spent the

evening chatting in the parlor with Mrs. Townes and Mrs. Porch (her

neighbor) and went for a ride with Miss Metz of the kindergarten.

"Elwell left for Key West that night." |

Saturday, April 16, was a "fine day."

She mentions "War News" and a report that troops are coming to Tampa

and that "Tampa will be a center." (War on Spain had not yet

been declared.) A telegram from her nephew, S.E.B. urges her

to come to Washington and leave her staff in Tampa. She wrote

letters to various Red Cross personnel, "men do banking, get passes.

A busy afternoon." She packs her satchel in minutes, makes no

change (of clothes?) leaves Cotrell $50 (he had previously drawn a

check for $200) and she leaves for the train station at 7:30

pm. "Wait at train station until 9pm, after having driven at a

gallop to get there. Took train and berth."

Zoomable view of Clara's journal from April 15 to April 17,

1897 |

|

Tampa to Jacksonville and Washington, DC.

|

|

Sunday, April 17 - Clara arrived in Jacksonville a half hour

too late and missed the next train which left 20 minutes earlier.

She didn't go to a hotel, instead she had breakfast in the

restaurant at a table in the corner and wrote and read all day until

4 pm when she met a friend of Egan's and took a long ride.

Numerous notes on sending dispatches to NY, Wash. & Tampa and

comments on various Red Cross activity concerning authority.

Her train to Washington left at 8pm. |

Monday, April 18 - Notes about her

activity on the train ride from Jacksonville to Washington DC,

beginning at 7 am.

Zoomable view of Clara's journal from April 17 to April 19

Tuesday, April 19

through Thursday April 21 - Clara writes about many things from

her home in Glen Echo, MD.

On April 21 she notes that "War news gets bad." |

| |

|

| |

|

|

This is not typical of Clara's

handwriting,

which is typically quite illegible. |

This

is the page numbered "00" at the top which Clara referred to at the

beginning of this No. 2 book of notes on Cuba--Names of persons she

met on this trip. The

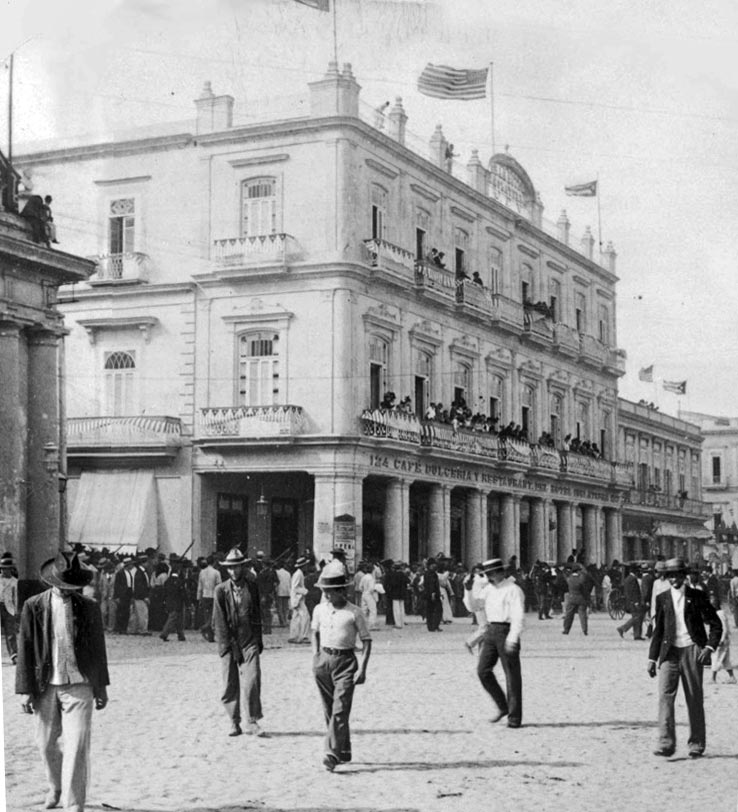

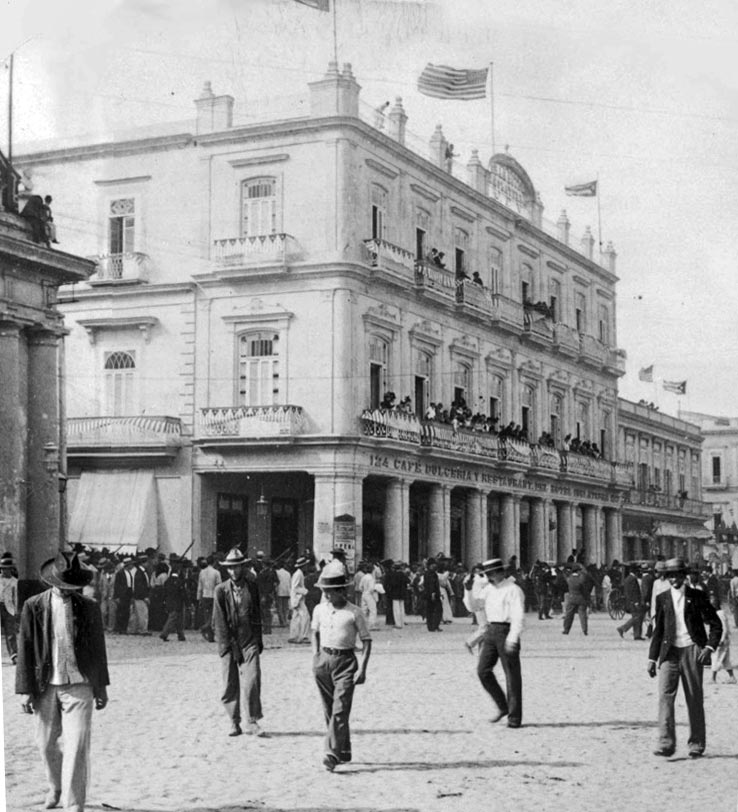

Hotel Inglaterra (Spanish for "England") still stands in Havana

today.

The Hotel Inglaterra, as it would have

looked when Clara was there

seen here, ca. 1900

Photo from Secrets of Cuba Culture Forum

(This site has many rare, old photos of Cuba from this time period) |

|

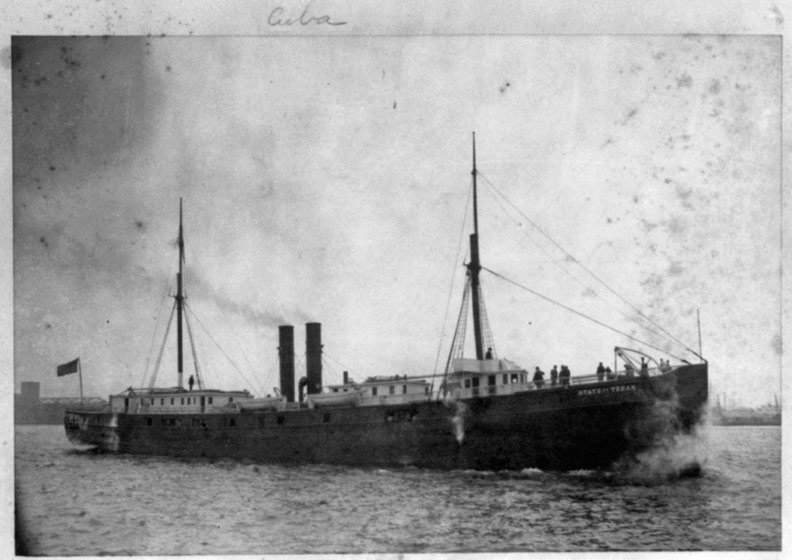

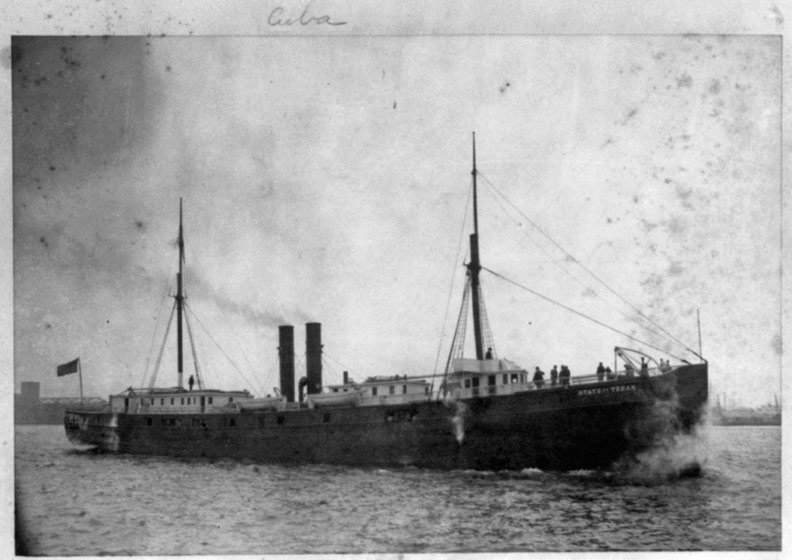

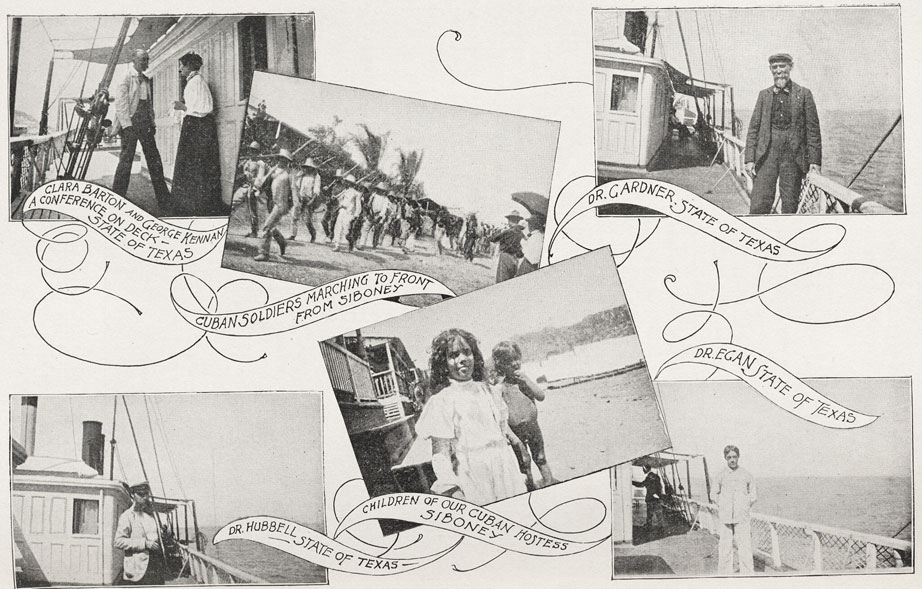

Red

Cross relief ship "State of Texas"

Early in April it had been decided to charter a steamer in New York

and to load her with supplies and send her to different ports in

Cuba, where her cargo could be unloaded in such quantities as might

be required. Accordingly, the steamer "State of Texas," of about

eighteen hundred tons burden, was chartered from Messrs. Mallory &

Co., of New York, and notwithstanding the fact that our party had

been obliged to leave Havana, and that subsequently war had been

declared, the preparations for sailing were kept up, and the steamer

was loaded with a cargo of fourteen hundred tons, which embraced a

fine assortment of substantial and delicacies, and many household

articles, medicines and hospital stores. When she was finally loaded

in the latter part of April, the "State of Texas" sailed for Key

West in charge of Dr. J. B. Hubbell, with Captain Frank Young as

sailing master, arriving there on the twenty-eighth of that month.

From

The Red Cross, A History of this Remarkable International

Movement in the History of Humanity

Red Cross relief ship "State of Texas"

Photo courtesy of Library of Congress |

|

Friday, April 22 - Clara is at home in Glen Echo having

arrived on the train at 7:30 am. Numerous notes regarding

several people. |

Saturday, April 23 - Clara mentions "Ship sailed 8 1/2

(8:30) a reference to the Red Cross relief ship "State of Texas"

leaving NY for Key West. |

|

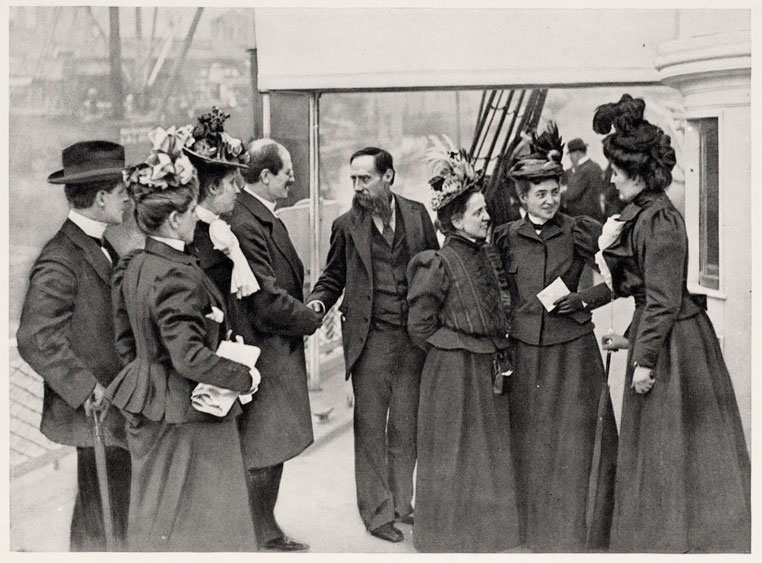

The State of Texas

relief ship leaves New York for Key West and Cuba

Departure of the Red Cross relief ship State of Texas from

New York to Cuba on April 23, 1898.

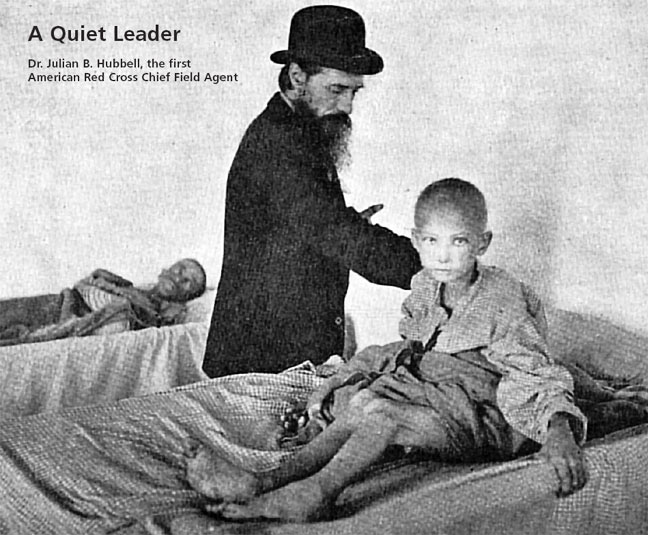

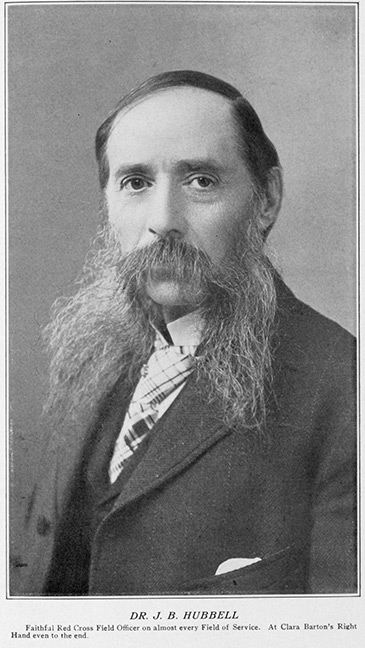

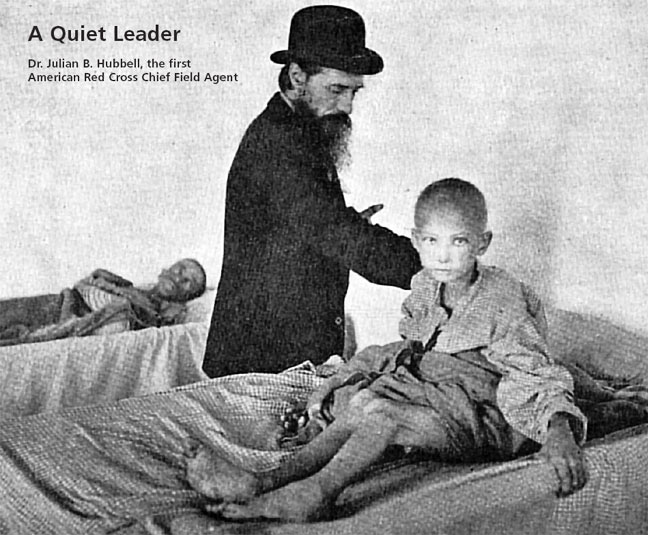

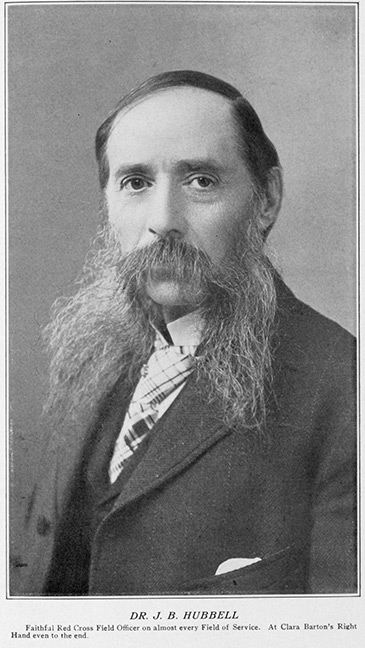

Dr. A.M. Lesser of the Red Cross Hospital bids farewell to Dr. Julian B.

Hubbell (bearded), Field Agent of the Central Cuban Relief.

Photo from the National Park Service Museum

Clara Barton described

the qualities of the ideal American Red Cross field agent:

“The ideal

field agent should possess: the ability to view a situation

broadly without scorning details, an objective mind mellowed by

sympathetic understanding, a liking for hard work, willingness to

cooperate with others, belief in what the Red Cross stands for,

executive talents, but willingness to subordinate his/herself.”

Read about Dr. Hubbell at

A Quiet Leader, Dr.

Julian B. Hubbell, the first American Red Cross Chief Field Agent

Image from "In Memoriam" Clara Barton Tribute, 1912 |

|

Sunday, April 24 - Glen Echo - Clara mentions the ship

"State of Texas having left yesterday and expects to arrive in Key

West on Thursday and she plans to leave Glen Echo tomorrow (Monday.) |

|

U.S.

declares war on Spain

|

|

|

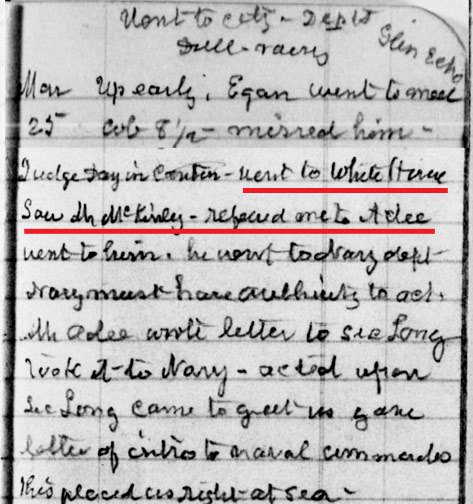

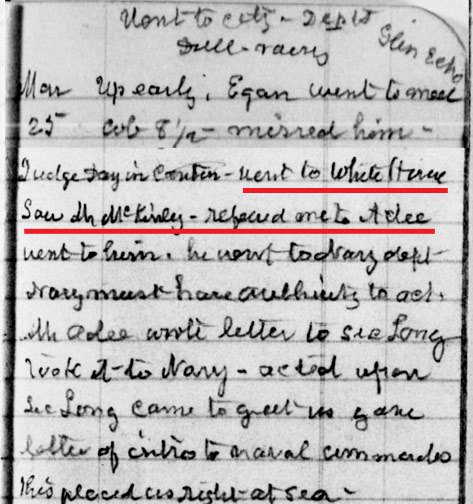

Monday, April 25 - Clara goes to the White House and meets

with Pres. McKinley and Sec. Alvey Adee regarding getting letters of

authority so she and the Red Cross can pass through the US blockade

of Cuba. Adee writes a letter to Sec. Long. This is the

day the U.S. declared war on Spain.

At the declaration of war on April 25th, the American Red Cross in

Tampa was ready to offer immediate war service, and in spite of war,

Barton hoped that her relief work would continue. Two days before

the outbreak of war, the Red Cross relief ship, the State of

Texas, left New York harbor laden with 1,400 tons of supplies

for the reconcentrados. Barton was anxious that the Geneva

Convention did not cover naval warfare at this time. Moreover, in

war, the Red Cross was supposed to have an active role with the

military. She appealed to military leaders to follow the Geneva

accords, but she found the same prejudices against her and “her”

organization as she had in the Civil War. The generals believed that

volunteer committees were unnecessary and that the military should

take care of its own medical needs. |

| |

Before the “State of Texas”

arrived at Key West, war had been declared between the United States and Spain,

and soon after the prize ships, schooners, steamers and fishing smacks, captured

off the Cuban coast began to come in, in tow, or in charge of prize crews. The

Navy worked rapidly and brought in their prizes so quickly that the government

officials were not prepared to feed the prisoners of war. On the ninth of May

the United States Marshal for the southern district of Florida made the

following appeal:

Miss Clara Barton,

President, American National Red Cross:

Dear Miss

Barton: On board the captured vessels we find quite a number of aliens among

the crews, mostly Cubans, and some American citizens, and their detention here

and inability to get away for want of funds has exhausted their supply of

food, and some of them will soon be entirely out. As there is no appropriation

available from which food could be purchased, would you kindly provide for

them until I can get definite instructions from the Department at Washington?

Very respectfully,

John F. Horr,

U.S. Marshal.

From The Red Cross in Peace and War by Clara Barton

|

Clara heads back to

Tampa and Key West to join the relief ship State of Texas

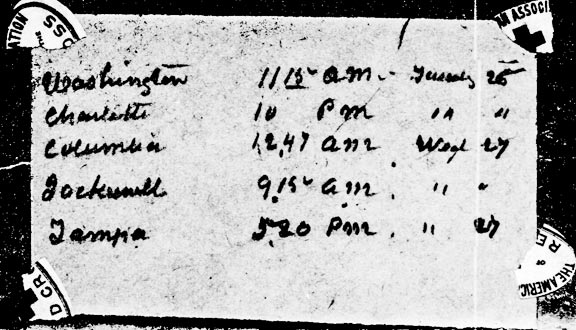

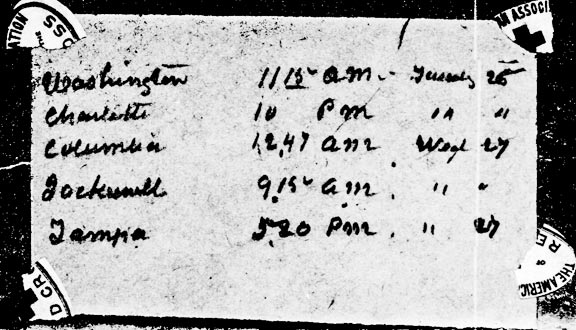

Clara made note of her itinerary for this

trip and affixed it to the cover of her No. 2 journal of her notes

on Cuba.

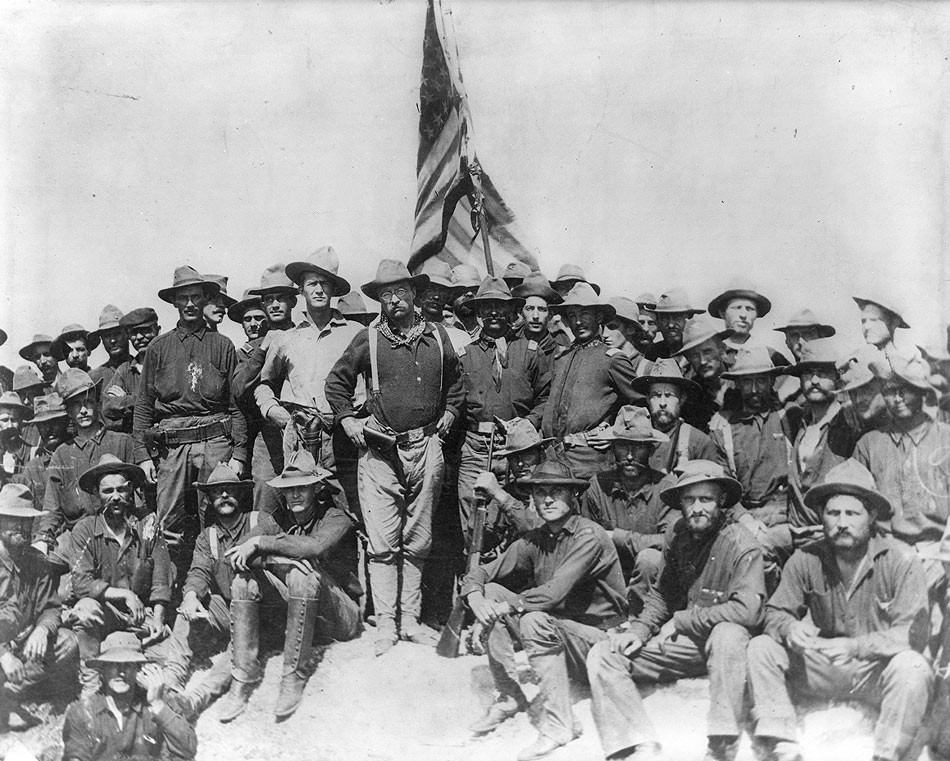

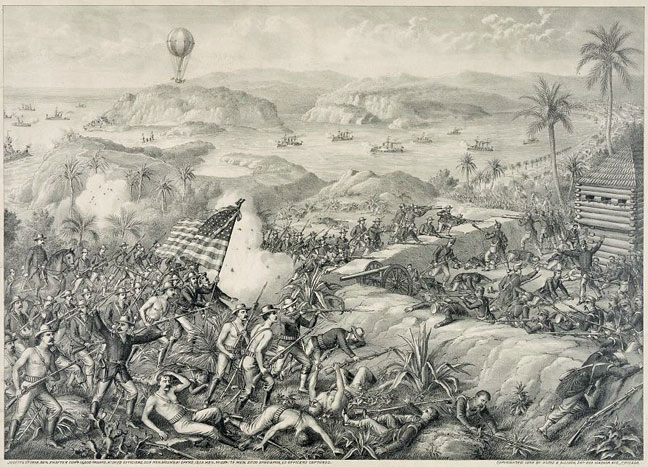

The Scene at the Tampa Bay Hotel

In 1898 H. B.

Plant's Tampa Bay Hotel became headquarters for the top brass of

the U.S. Army during the Spanish American War as Tampa was the

debarkation point for troops going to Cuba. A young relatively

unknown officer named Theodore Roosevelt camped nearby with his

"’Rough Riders" but his wife stayed at the "big hotel".

Generals Joe Wheeler, John B. Gordon, Fitzhugh Lee and Nelson A.

Miles were some of the brass who mapped strategy from the

verandahs of the hotel.

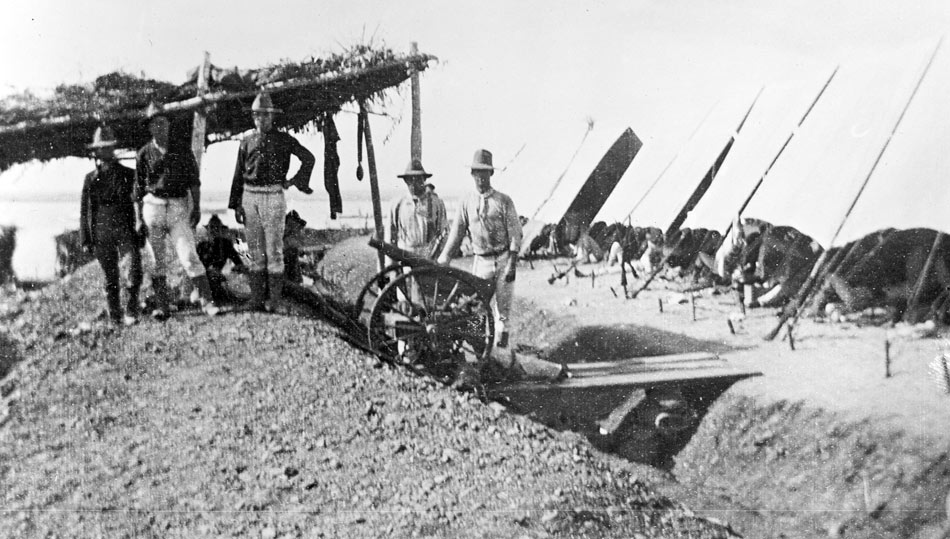

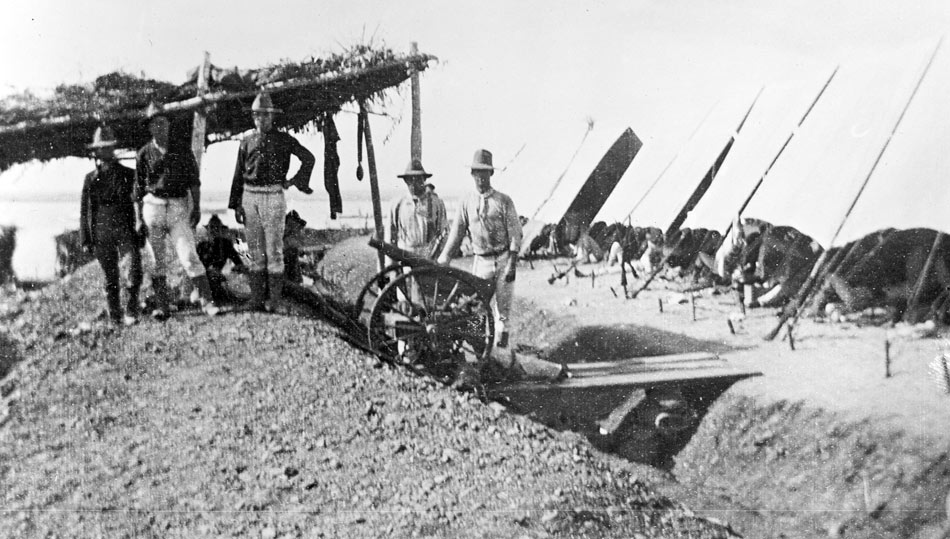

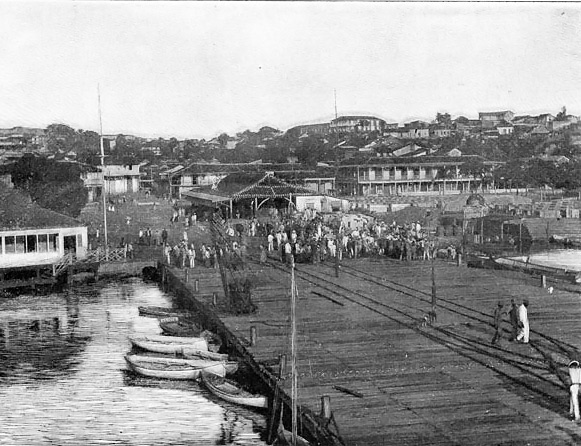

Generals Nelson A. Miles, Joseph Wheeler and

staff in front of officers quarters on Picnic Island: Port Tampa

City, Fla.

Gen William Ludlow,

April 1898

Photo courtesy of the Harvard University Library, Dwight L.

Elmendorf Spanish-American War photographs

|

|

|

|

March 27, 1898 -

Burial of the "Maine" victims, taken at Key West.

First comes a detachment of sailors and marines in the left

foreground, while at the right is seen a crowd of small

colored boys, which preceded any public procession in the

South. Then follow the nine hearses, each coffin draped with

the flag. At the side of each wagon walk the pall bearers,

surviving comrades, their heads bowed in attitudes of grief.

Next come naval officers and marines, and lastly a

procession of carriages, followed by a large crowd on foot. |

May 20,

1898 Tampa - Military camp at Tampa, taken from train

From Edison films "war extra" catalog: A wide plain, dotted

with tents, gleaming white in the bright sunshine. Soldiers

moving about everywhere, at all sorts of duties. In the

background looms up a big cigar factory; giving the prosaic

touch to the picture needful to bring out in sharp contrast

the patriotism with which the scene inspires us. The camera

was on a rapidly moving train, so the panoramic view is a

wide one, and remarkably brilliant. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

May 1,

1898, Ybor City. Hurrah--here they come! Hot, dusty,

grim and determined! Real soldiers, every inch of them! No

gold lace and chalked belts and shoulder straps, but fully

equipped in full marching order: blankets, guns, knapsacks

and canteens. Train is in the background. Crowds of curious

bystanders; comical looking "dude" with a parasol strolls

languidly in the foreground. Small boys in abundance.

The column marches in fours and passes through the front of

the picture. More small boys--all colors. The picture is

excellent in outline and full of vigorous life. |

May-June, 1898

Tampa - Shows the wonderful intelligence of these

Troop F, 6th U.S. Cavalry, horses. At a command they lie

down promptly, and at another order scramble to their feet.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

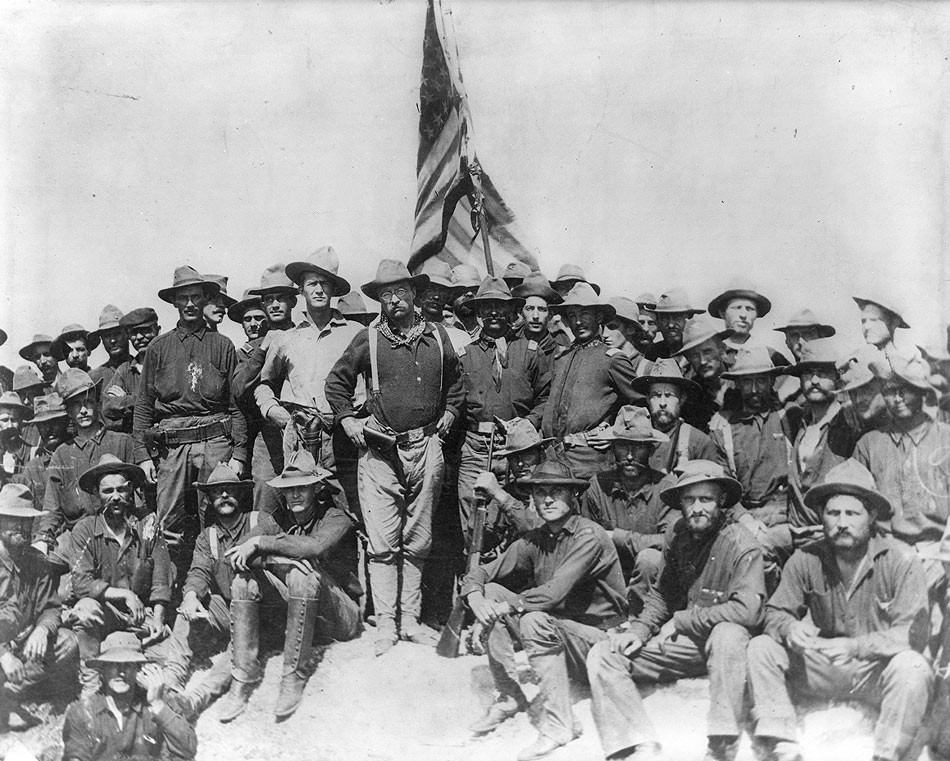

Circa April 1898

in Tampa - Roosevelt Rough Riders. A charge full of

cowboy enthusiasm by Troop "I," the famous regiment, at

Tampa, before its departure for the front. Roosevelt

and his Rough Riders were encamped in West Tampa in the area

that is now between Ft. Homer Hesterly Armory and Kennedy

Blvd, along Howard Ave. See

Ft. Homer Hesterly Armory at TampaPix.com

|

The transport

Whitney leaving Port Tampa for Cuba, May 20,1898 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Jun 8, 1898 - Roosevelt's

Rough Riders embarking for Santiago, Port of Tampa -

Soldiers in Spanish-American War uniforms moving boxes

towards a steamship on the dock |

January 1, 1899,

in Havana, Cuba.The troops are turning into the Prado from a

side street, where stands a triumphal arch erected by the

Cubans; but which Gen. Brooke, the Military Governor of

Cuba, would not permit to be finished, as he allowed no

demonstrations of any kind. The soldiers are the First Texas

troops. The streets are crowded with people. Many typical

Cubans are seen lounging in the foreground, with here and

there a Spaniard, if one may judge by sour looks and solemn

demeanor. The buildings are all low stone structures, with

heavy barred windows, from which are displayed small Cuban

flags. An excellent picture of life in Havana. |

Library of Congress Channel at YouTube

Spanish American war period films shot in Tampa

on Library of Congress Website

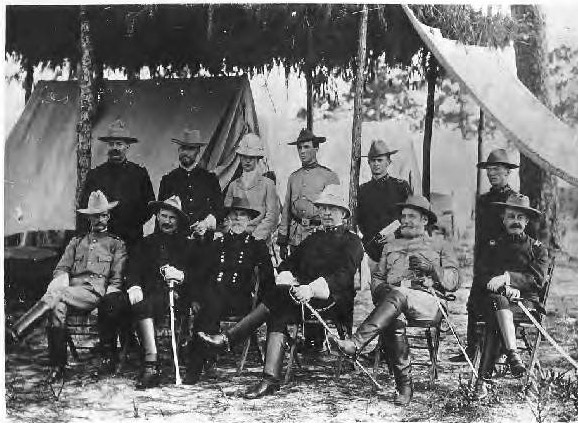

Generals James F. Wade,

McClure, and Ramsey on the verandah of the Tampa Bay Hotel, April

1898.

Photo courtesy of the Harvard University Library, Dwight L.

Elmendorf Spanish-American War photographs

|

|

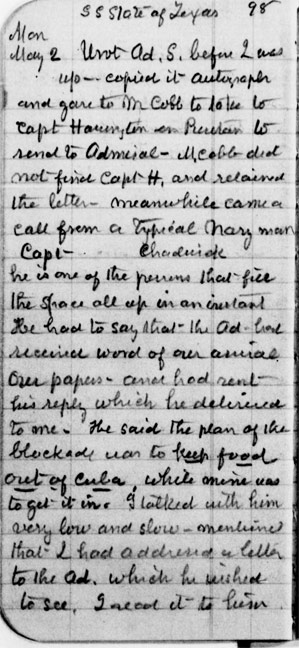

Tuesday, April 26 -

Clara takes the 9:30 train from home

to catch the 11:15 from Washington for Jacksonville. Rainy,

dull day all the way to Jacksonville.

Wednesday, April 27 - Tampa

- She meets the Taliaferros of

Jacksonville onboard. Clara arrives in Tampa at 5:30 pm and

home in time for supper.

|

CLARA BARTON IN TAMPA

New York Times, April 28, 1898. TAMPA - Apr. 27 - Miss Clara

Barton of the Red Cross Society arrived here to-night from

Washington, and she, with the entire Red Cross force, will leave

Tampa to-morrow for Key West.

New York

Times, April 29, 1898.

TAMPA - April 28 - Gen. Wade and his staff made an official call to-day on

Miss Clara Barton and they had an important conference of half an hour.

The exact nature of it is not known, but Miss Barton admitted that her

future movements were concerned in it. To-night Miss Barton and those of

the society who were with her left on the steamship Mascotte for Key West.

|

|

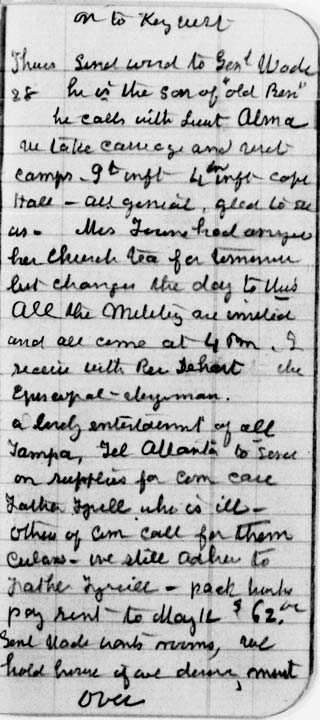

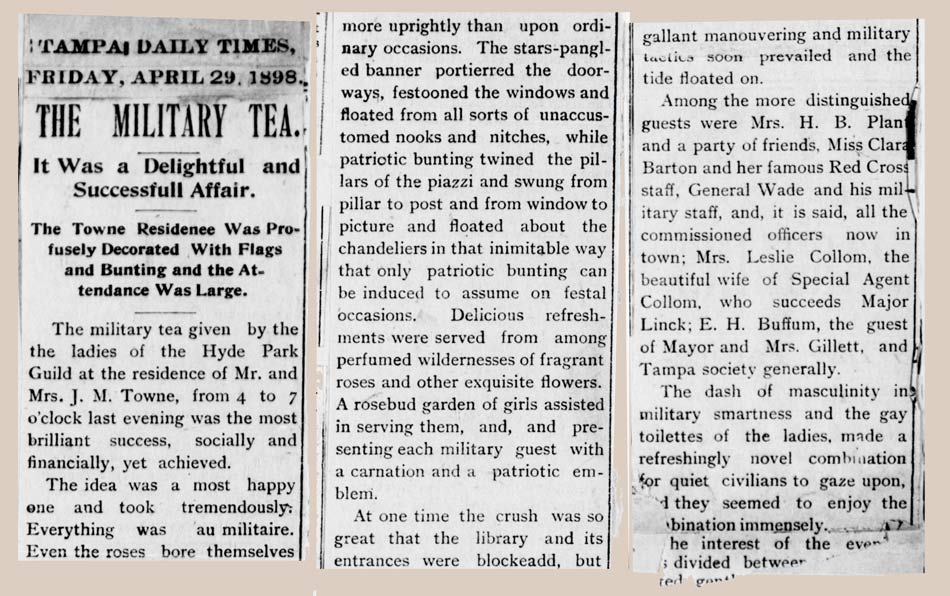

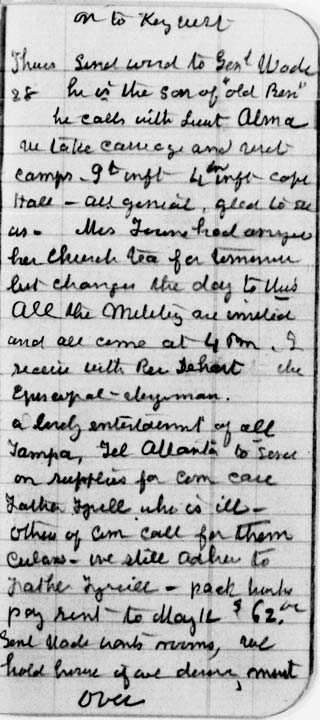

Thursday, April 28 - Tampa - Sent

word to Gen Wade he is the son of "old Ben" he calls with Lieut

Alma We take carriage and visit camps 9th inft - 4th inft Capt

Hall - all genial, glad to see us. Mrs Towne had arranged her

church tea for tomorrow but changes the day to Wed. All the

Military are invited and all came at 4 pm. I receive with Rev

Dehart he [illegible] - clergyman. A lively

entertainment of all Tampa. Tel [telephone] Atlanta [?]

to send on supplies for com ca.. Father Tyrell who is ill - others

of com call for them Cubans - we still adhere [?] to Father

Tyrell - pack trunks pay rent to May 12 $62. Gen Wade wants rooms,

we hold ...[ illegible]

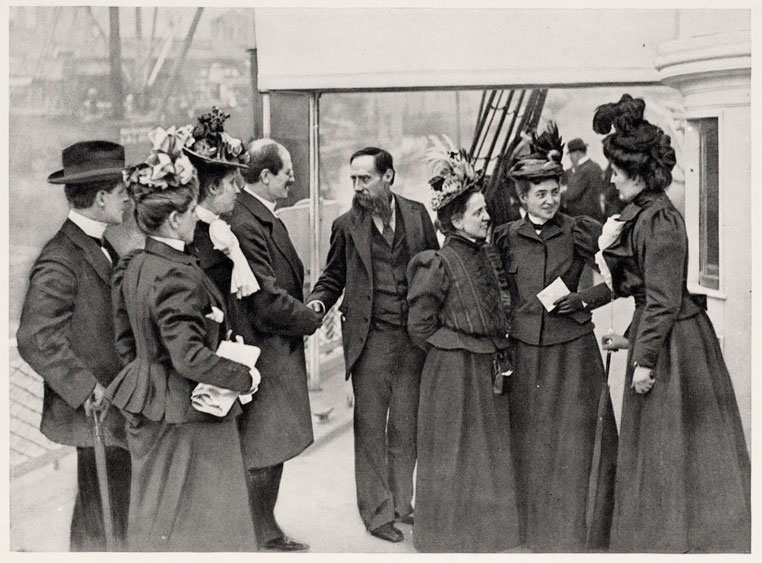

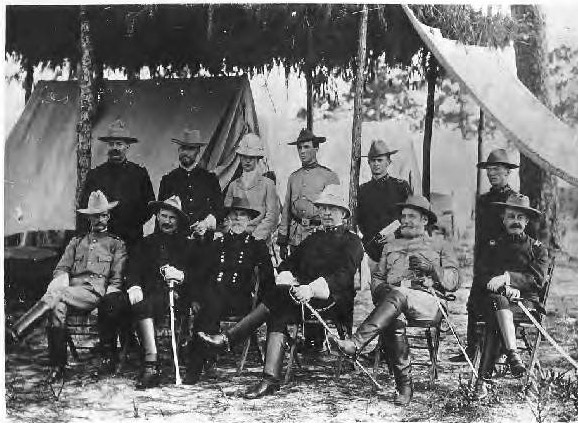

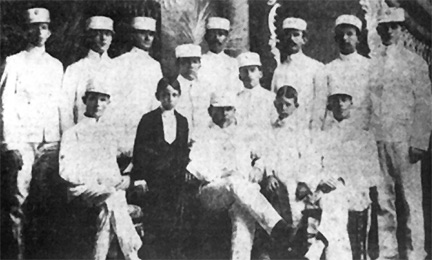

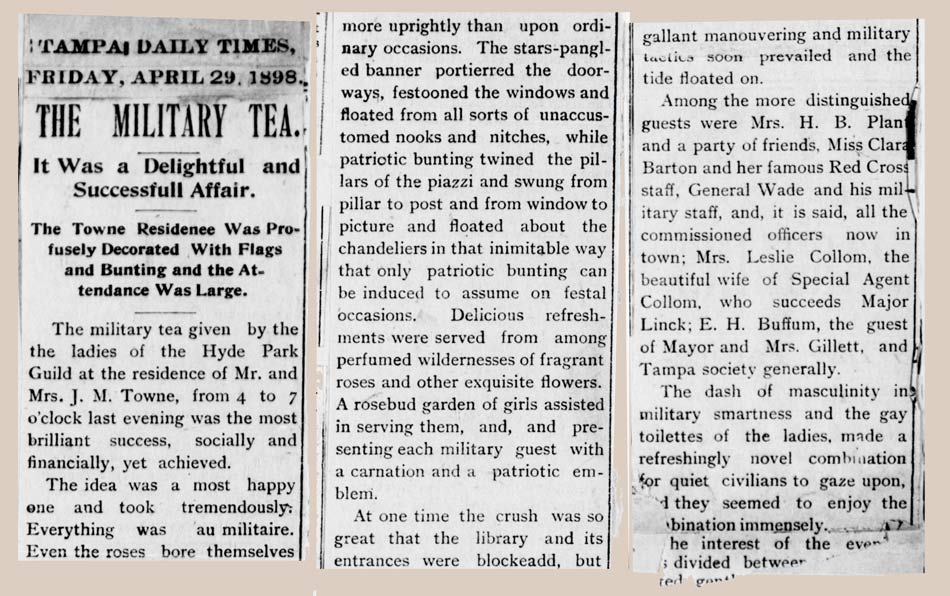

The

photos below

were taken at the Towne residence at 350 Plant Avenue on Thursday,

April 28, at a "Military Tea" given by the ladies of the Hyde Park

Guild. It is the day she spent in Tampa on her way to meet

the State of Texas in Key West. Clara mentioned the next

day, those who were on the train to Port Tampa to board the

Mascotte: Dr. Joseph Gardner and his wife Enola, Miss Lucy

Graves, four nurses, Dr. E.Winfield Egan (Red Cross Surgeon), Mr.

C.H.H. Cottrell (Red Cross Financial Secretary), J.K. Elwell, and

J.A. McDowell. The photo is most likely those persons.

Notice the four nurses in the photo, along with two other women

(Enola Gardner and Miss Graves) and 6 men (only one not named.)

Photo from

American Red Cross Blog |

|

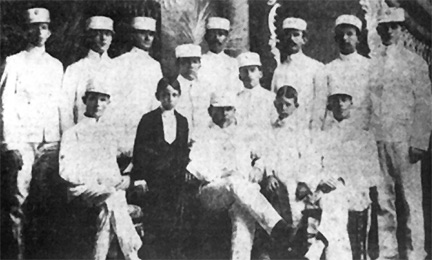

Photo

below from "The

Red Cross in Peace and War" - A PART OF THE RED CROSS CORPS

that was working with the Reconcentrados in Cuba before the

declaration of war, waiting at Tampa, Florida, for the Red Cross

Relief Ship “State of Texas,” to carry them back to Cuba to resume

their work. The address of the house can be seen just above

the small U.S. flag on the wall behind the nurse.

Military tea in honor of Gen. Wade and staff at

the home of Mr. & Mrs. J. Mack Towne in Hyde Park, Tampa, Fla.

Miss

Clara Barton is seated in the center of the group.

Place your cursor

on the photo to see persons identified compared to picnic photo.

L to R: J.K.Elwell, J.A. McDowell, nurse1, Dr. Jos. Gardner,

unknown man1, nurse2, Miss Barton seated, unknown man2, nurse3, unknown

man3 (may be David L. Cobb, Red Cross Counsel), Enola Gardner, nurse4,

Lucy Graves.

The four nurses appeared in

another photo (see further down) and are identified by Miss Barton in a

letter she wrote on March 22, 1899.

They are Miss Isabelle Olm, Miss

Annie McCue, Miss Blanche MacCorriston, and Miss Minnie Rogall. (not

necessarily in order here.)

Photograph by Gevit Parlow.

Other photos by Gevit Parlow

See Clara's journal for April 27 & 28

Towne was the owner

of Towne's Tampa Steam Laundry. Photo at right shows

J. Mack Towne seated at center with his staff and his son, D. P.

Towne dressed in black, standing next to him, 1903.

Another photo was taken at the same occasion on

the front porch of the Towne residence.

Clara Barton (at center) and some of the same Red Cross volunteers

outside the home of J. Mack Towne located at 350 Plant Avenue.

Clara Barton and her Red Cross volunteers outside the

home of J. Mack Towne at 350 Plant Avenue.

Photo from Tampa Tribune Online article by Paul Guzzo, credit to Tampa

Bay History Center.

Below: The Towne residence in 1903.

From "Tampa

Illustrated" at Internet Archive, compiled and published by C. E.

Bissell and Roy Dougherty in 1903.

Photo by Fred Barker.

Below, from the

Clara Barton/Red Cross scrapbooks online at the Library of

Congress.

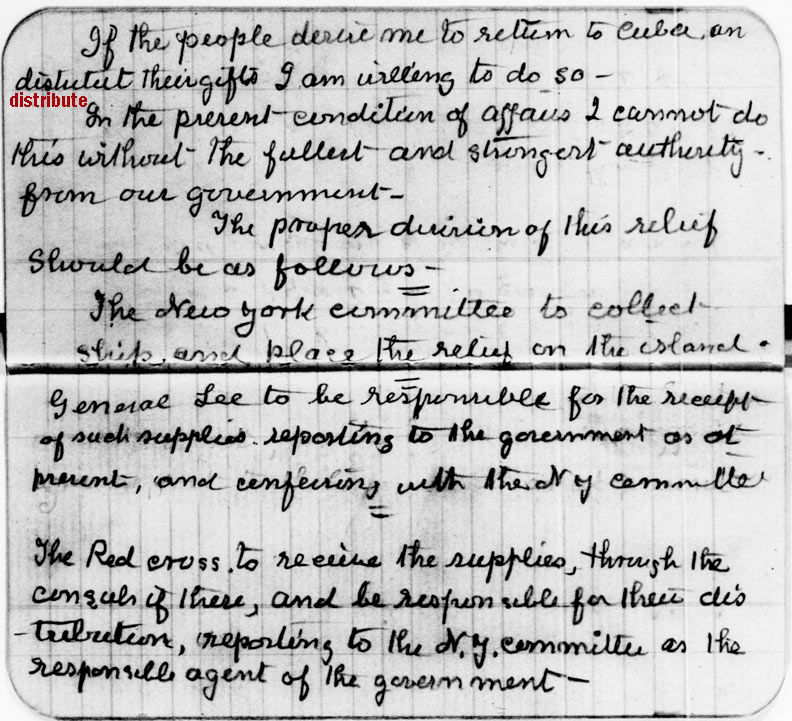

On the next two pages, Clara turned her

journal sideways and wrote the following:

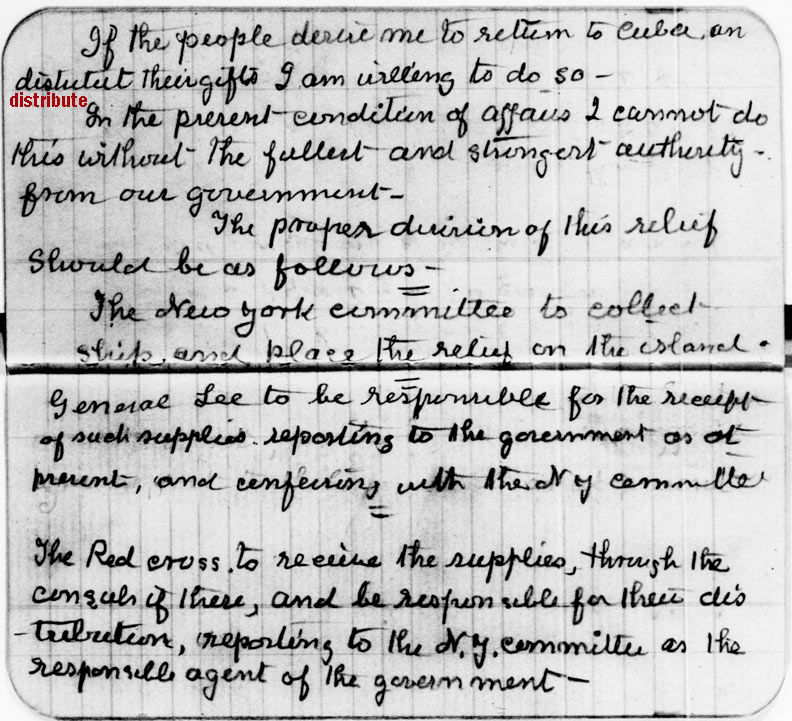

If the people desire me to return

to Cuba and distribute their gifts, I am willing to do so.

In the present condition of affairs I cannot do this without

the fullest and strongest authority from our government.

The proper division of this relief

should be as follows:

The New York committee to collect, ship and place the relief

on the island. General Lee to be responsible for receipt of

such supplies, reporting to the government as at present, and

conferring with the NY committee.

The Red Cross to receive the

supplies, through the consuls if there, and be responsible for

their distribution, reporting to the NY committee as the

responsible agent of the government.

|

|

|

| Thursday, April 28

(continued)

Tampa

to Key West to join the relief ship "State of Texas"

In her book, The

Red Cross, A History of this Remarkable International Movement in

the History of Humanity, Clara wrote about this day:

In the meantime, Dr. Jos. Gardner and

wife, of Bedford, Ind., had joined our party at Tampa; and

soon after Miss Barton, Dr. Egan, Mr. D. L. Cobb* and Miss Lucy

M. Graves came along, and it was arranged that the entire

party was to leave Tampa on the evening of April 28, to go aboard

the steamer "State of Texas," at Key West, and remain on her until

the army had made a landing in Cuba, when it was expected that we

should be able to resume our work there. The day of the evening we

were to leave Tampa, Mrs. J. M. Towne, the lady at whose house our

party was stopping, gave a reception in honor of Miss Barton, to

which General Wade and the army officers who were then stationed

there, and many ladies and gentlemen of that fine little city,

were invited. It was a most brilliant and enjoyable occasion, the

uniforms of the officers and the lovely toilettes** of the ladies

making a picture that will long remain in the memories of those

who saw it.

*David

Lewis Cobb was counsel to the National Red Cross.

**Toilette - Dress, attire; costume.

|

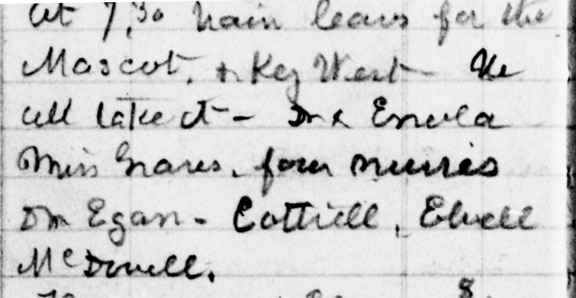

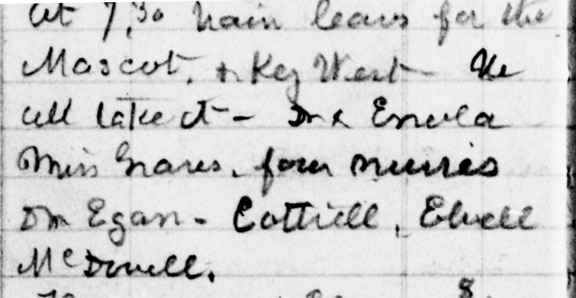

In her journal, Clara wrote: ..."at 7:30

train leaves for the Mascot to Key West. We all take it,

Dr. & Enola [Dr. Joseph Gardner and his wife Enola], Miss

Graves [Lucy], four nurses, Dr Egan, Cotrell, Elwell,

McDowell. Mr. and Mrs. [H.B.] Plant came out to see us

at hotel and came to reception. We reach boat and leave

at 10. o'clock.

(Before Enola

Lee's marriage to Dr. Gardner in 1888, she was Clara's friend

and secretary. When Enola announced to Clara that she

was to marry Dr. Gardner, she promised that she and her

husband would continue to work with her anywhere they might be

needed.)

|

|

|

Lawrence County Museum of History |

|

Clara and her entourage leave Tampa to join the relief

ship State of Texas in Key West

Friday, April 29

-

SS

Mascotte to Key West

- After landing in Key West she meets Hubbell and passengers of the

State of Texas, Captain Young, "she is far off." Gives papers

to Commander Forsyth who refers her to Capt. Harrington of the

Puritan who came on to her tug. Delivered papers and went onto

the ship. "A nice ship, well manned. Supper. Mr.

Mann historian, Mr. Bangs, Mr. Duncan, supper, room, bed.

See journal pages for April 28 & 29

Waiting

in Key West for clearance from the US Navy to enter Cuba

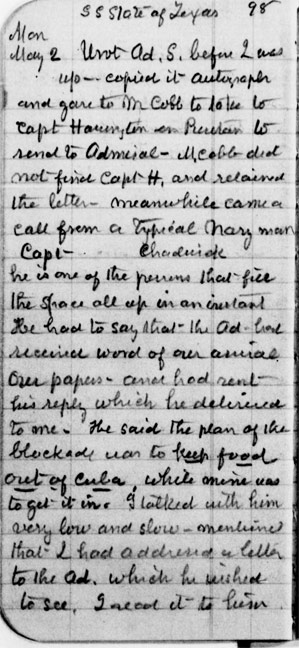

Saturday, April 30 - Onboard the State of Texas, Key West harbor

- Clara spends much time on the ship docked in Key West, waiting for

the Navy to allow the State of Texas to pass through the blockade

with their supplies. She writes about many things in the

oncoming weeks. The events of the war, the business of the Red

Cross, banking activities, shore excursions, etc. She uses up

the pages in her 2nd book on her activities concerning Cuba and

starts a new book where her handwriting vastly improves. On

May 10 she goes in to detail about the "Prize ships"--ships that the

U.S. has captured and brought to Key West with their crew.

Clara records the names of some ships and tells about

distributing food and supplies to them. All this goes on for

about a month.

While we were lying at Key West there

was scarcely a day passed that some of our vigilant blockading

squadron did not bring in from one to three captured prizes;

sometimes large steamships, and from that class through the

various grades of shipping down to fishing smacks; and in the

course of a couple of weeks there were between thirty and forty of

these boats lying at anchor in the harbor, with their crews aboard

under guard. Somehow it was forgotten that these poor foreigners

must eat to live; or else perhaps somebody thought that somebody