A BRIEF HISTORY OF

SOME OF TAMPA'S WATERWORKS & SPRINGS

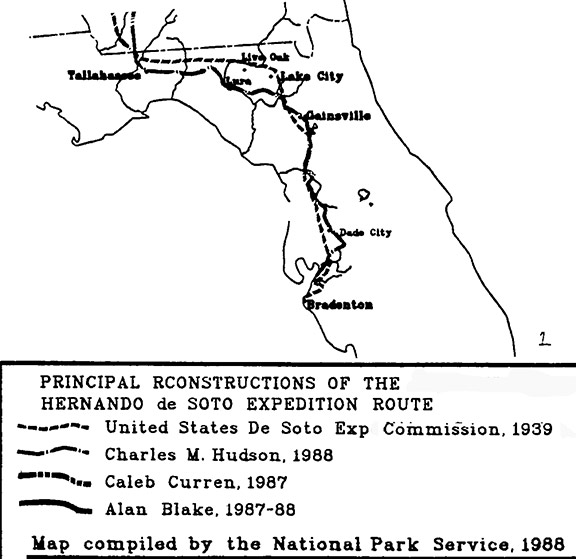

THE GOVERNMENT SPRING

A historical marker formerly located near 5th Avenue and 13th

Street, erected by the Ybor City Rotary Club, commemorated the

site of a historic spring which served as the earliest source of

water for

Fort Brooke and an Indian encampment. It read:

Tampa's oldest and most romantic landmark.

For centuries the ancient Timuquan Indian Tribes used this

spring as a shrine to their water-gods. The Spanish

Conquistadores tarried here, and the early pioneers found

sustenance from the magic waters. For more than 60 years this

spring supplied water for Fort Brooke. During the Seminole

Indian Wars famous history making men planned their campaigns

here. Among them were: General Winfield Scott, General Zachary

Taylor, General David E. Twiggs, General Edmund P. Gaines,

General Thomas H. Jessup, and General Abraham Eustis. In 1896

Florida's first brewery was erected here. For many years the

pure water from this famous spring was used to brew La

Tropical Beer.

The

first road connecting Fort Brooke to Fort King near present-day

Ocala, about one hundred miles away, was constructed by the U.S.

army in 1825 and ran through the heart of the wilds of today's

Ybor City, with two offshoots leading to the spring. The

first road connecting Fort Brooke to Fort King near present-day

Ocala, about one hundred miles away, was constructed by the U.S.

army in 1825 and ran through the heart of the wilds of today's

Ybor City, with two offshoots leading to the spring.

The road was built from Ft. Brooke (now the Channelside area)

through the salt marshes of what was the Ybor Estuary (the Port of

Tampa area) to the large spring at the present site of Fifth

Avenue and Thirteenth Street.

Since the spring was located on government land, the spring was

named Government Spring. This two-mile strip of road was the first

to be built in South Florida, and provided a shortcut from the

fort to the spring. The water was transported in barrels on

mule-drawn wagons. Many notable military men and scouting parties

stopped at this historic spring to fill their canteens and water

their horses before leaving on expeditions into the forest.

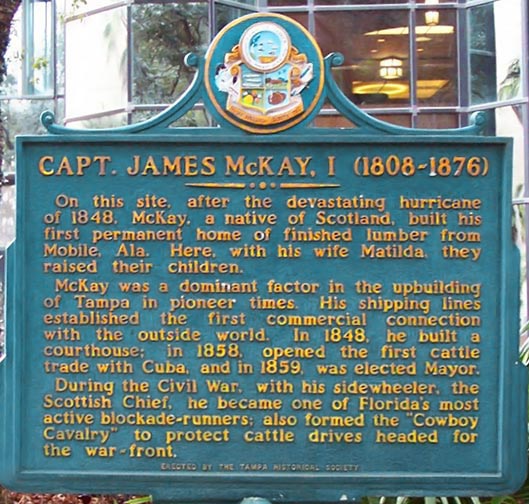

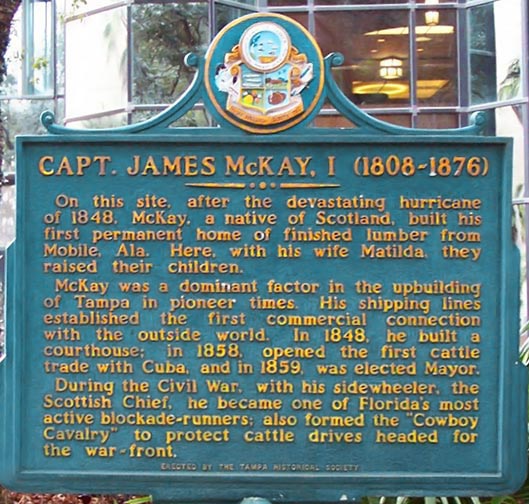

In

the closing days of July, 1846, an intrepid young Scottish sea

captain, James McKay, with his expectant wife Matilda, their four

children, his spirited mother-in-law, Madam Sarah Call, their

eleven slaves, and household goods, all set sail on his schooner

from Mobile, Alabama, toward the wild frontiers of Florida and the

village of Tampa. This was the beginning of the McKay heritage in

Tampa, an illustrious family which has played a prominent part in

the development of Tampa for more than 130 years. In

the closing days of July, 1846, an intrepid young Scottish sea

captain, James McKay, with his expectant wife Matilda, their four

children, his spirited mother-in-law, Madam Sarah Call, their

eleven slaves, and household goods, all set sail on his schooner

from Mobile, Alabama, toward the wild frontiers of Florida and the

village of Tampa. This was the beginning of the McKay heritage in

Tampa, an illustrious family which has played a prominent part in

the development of Tampa for more than 130 years.

After Tampa was platted in 1847, Captain McKay began purchasing

land here. Old records show some of his early purchases – two

blocks from Jackson to Whiting Street, between Franklin Street and

Florida Avenue, the Knight and Wall block on Franklin and Kennedy,

and a large tract on the river which became the site of the Tampa

Waterworks in the late 1880s, and later became the police station

in the 1960s. On this site, now known as Tampa Heights,

McKay erected a large sawmill – the first mill in Tampa. The

sawmill on the “outskirts” of the village supplied the material

for building, and was an indispensable aid to the early settlers.

On July 12, 1884, Cyrus Snodgrass built the first ice plant on the

west coast of Florida at the spring site. The plant supplied ice

for the several fish companies which had moved to Tampa with the

coming of the railroad.

One fine spring day in 1885 the sleepy village of Tampa woke up.

That was the day, May 7th, when a body of inspired citizens

organized an enthusiastic Board of Trade which set about to

transform a tiny fishing hamlet into a productive metropolis. The

citizens were no longer content to reside in a faded military

outpost by the water, an isolated spot with deep sandy streets, a

few board sidewalks, frame buildings and no industry or commerce

to speak of.

Much of the success of the early days of Tampa's Board of Trade

undoubtedly was due to the enlightened leadership furnished by

that human dynamo, Dr. John P. Wall. This incredible man, a former

editor of the Sunland Tribune, a former mayor of Tampa, and

pioneering doctor in the research of the mosquito as the cause of

Yellow Fever, was in the forefront of every progressive move,

reached the climax of his colorful public service career in that

year 1885.

|

|

|

Capt. John T. Lesley

Vice-chairman of the Board of Trade |

THE

BEGINNING OF TAMPA'S WATERWORKS

During the winter of 1884-85, a series of disastrous fires

convinced everyone that a dependable water supply was essential.

In 1885, when the population of Tampa numbered 2,376, City

officials considered a system of waterworks for the community.

At its first session, the Board of Trade named a committee to "do

all possible for the success of the election on the City Water

works" and planned a public meeting to promote the project.

Captain John T. Lesley, former Tampa Mayor and vice chairman of

the Board of Trade, delivered an eloquent and forceful address in

support of the water works. They planned to use the water supply

from Government Spring, since the army for many years used the

water from this spring in preference to rain water. Laboratory

tests showed the spring water to be the purest and healthiest in

South Florida.

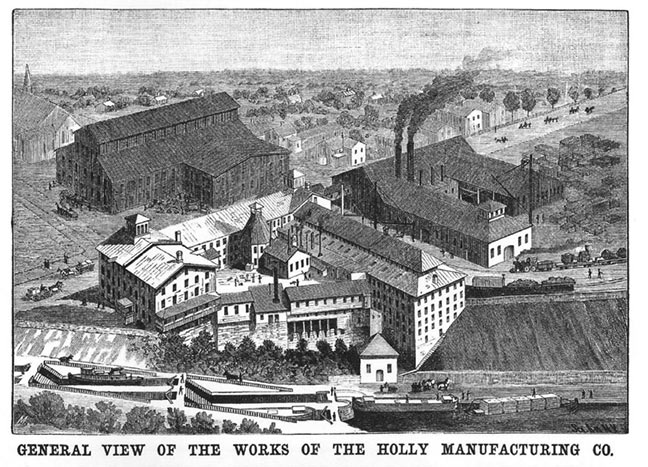

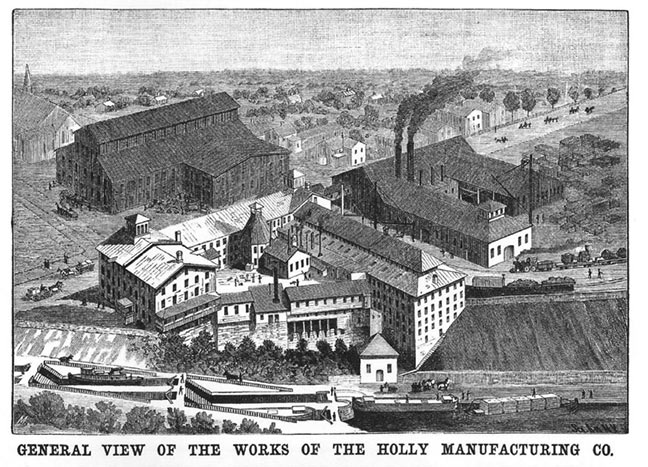

On July 28, 1885, the council awarded a franchise to the

Holly

Manufacturing Company, of Lockport, N.Y. The company agreed to

provide enough water for a town of 10,000 and install fifty fire

hydrants without charge. Water rates were fixed at $8 a year for

homes and from $15 to $50 a year for business places.

Postcard image from VintageMachinery.org

After getting the contract, the Holly officials lost their

enthusiasm. Making a house-to-house check to learn how many

families would take the "city water," they learned they could not

expect to get a gross revenue of more than $4,000 a year. That was

not enough to pay operating expenses, to say nothing of giving a

return on the initial investment, so the concern understandably

proceeded to forget the franchise.

Repeated attempts were made to interest other companies but

all failed because Tampa, then incorporated as a town, could not

obligate itself to pay for water hydrants.

That obstacle was

removed July 15, 1887, when Tampa was incorporated as a city. On

September 13 the new city council awarded a franchise to the

Jeter-Boardman Waterworks Company and agreed to pay $4,500 a year

for 110 hydrants.

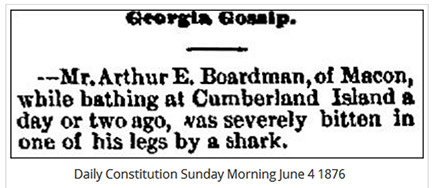

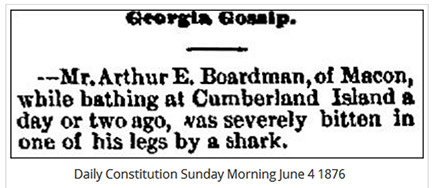

Arthur Edwin Boardman,

President of the Macon (Georgia) Gas, Light & Water Co., had been

elected city engineer in Macon in 1872. Arthur Edwin Boardman,

President of the Macon (Georgia) Gas, Light & Water Co., had been

elected city engineer in Macon in 1872.

William Augustus

Jeter was a man of many endeavors. He established mills,

factories, built a steamboat and ran a steamboat line, and

organized the Hawkinsville Brick Manufacturing Co. He

had contributed so much to the development of Hawkinsville, GA,

that in 1885 he was elected mayor.

In 1886, Jeter and

Boardman formed the Jeter & Boardman Gas & Water Co.

|

City of Tampa's

Incorporation History

|

-

January

25, 1849 - Village of Tampa elected 5 trustees with M.G.

Sikes elected president.

-

October

10, 1852 - Citizens voted to abolish the village

government.

-

September 10, 1853 - Citizens voted to organize as the

Town of Tampa with a Board of Trustee form of government.

-

September 15, 1855 - Citizens voted to abolish the Town

government and establish a City Charter.

-

December 15, 1855 - Governor Broome signed Special Act of

the Florida Legislature granting a charter for the City of

Tampa.

-

February 22, 1862 - The City Government was suspended by

Confederate Military Authorities during Civil War.

-

October

25, 1866 - Elections were held per Florida State

Legislature to reorganize the Incorporation of the City of

Tampa.

-

March

11, 1869 - The citizens of Tampa voted for the No

Corporation People's Ticket to disenfranchise the City

government.

-

August

11, 1873 - Citizens held a town meeting and voted to

re-incorporate as Town of Tampa.

-

July

15, 1887 - City of Tampa organized under a special act of

the Florida Legislature abolishing the governments of the

Town of Tampa and Town of North Tampa and establishing the

charter for the City of Tampa.

From City of Tampa Website

|

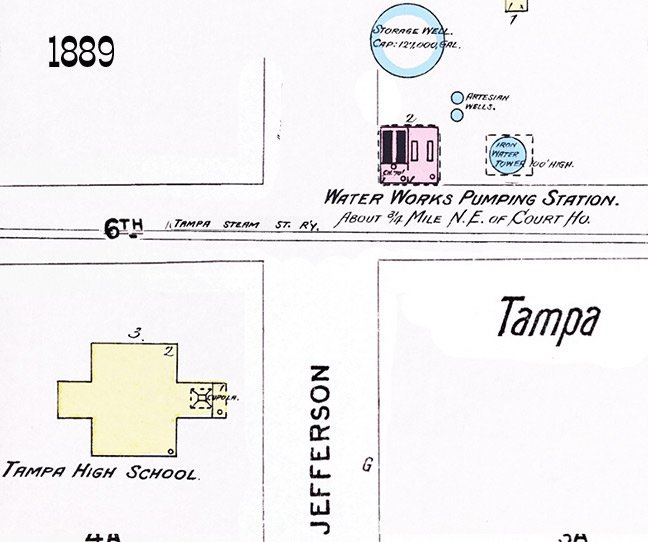

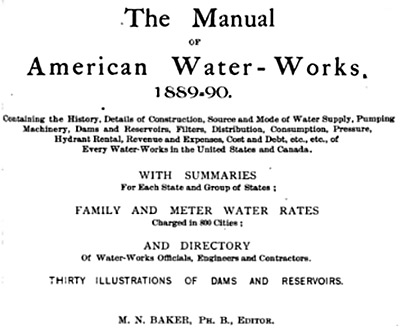

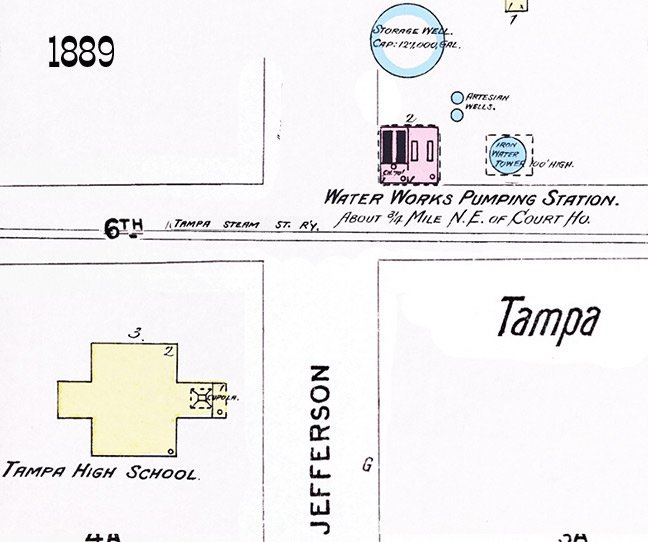

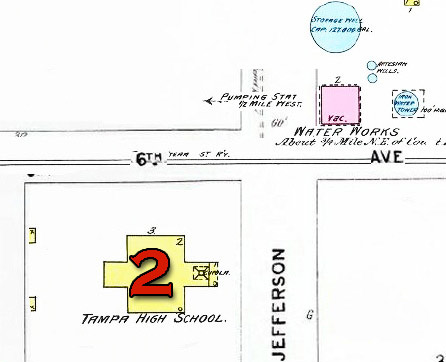

In

1888, the Jeter-Boardman Waterworks built

Tampa's first pumping station

at 6th Ave (a.k.a. Henderson St.) and Jefferson St, caddy-corner from the

2nd home of Hillsborough County High School which was

established there in 1886. Completion of the water system

made possible an effective fire fighting organization. Prior to

that time Tampa's firemen had been seriously handicapped by lack

of an adequate water supply.

|

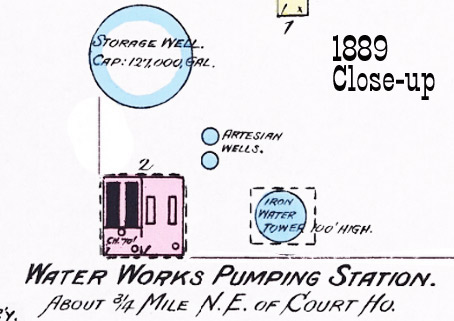

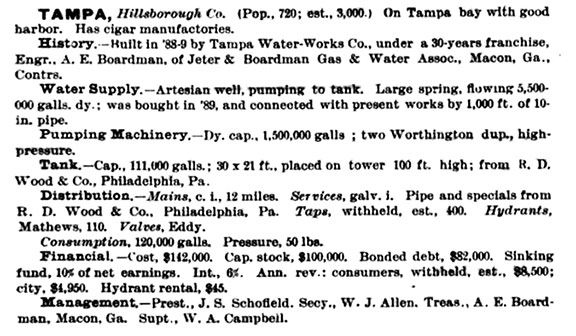

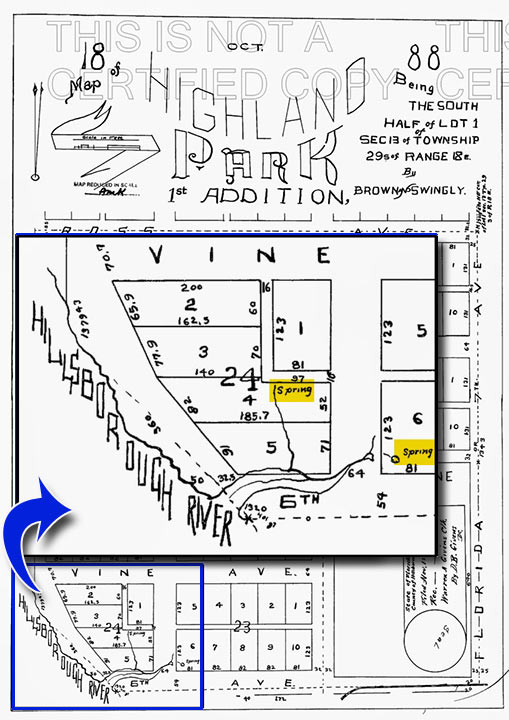

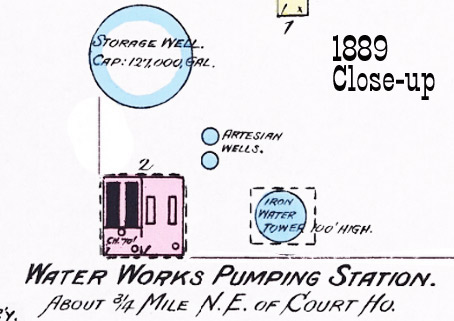

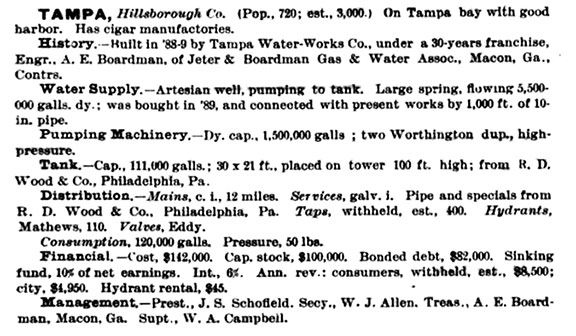

The 1889

maps above

(with 1899 streets added)

show Tampa's

first pumping station.

It consisted of a deep storage well and an iron

storage tank on a 100 ft. high tower. A detailed

description of the equipment is provided below.

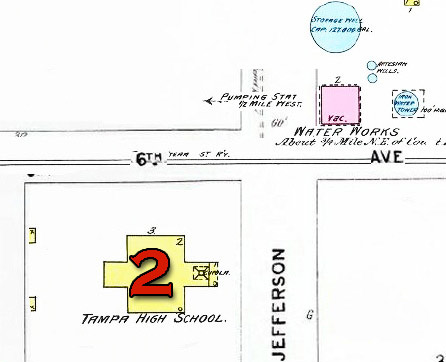

Manual of American Water-Works, Vol. 2, 1889-90

|

|

|

This 1892 map at left (with 1899 streets added) shows this first

pumping station as already vacant ("vac.") because by this

time, Tampa's second pumping station had already been built

"Pumping stat. 1/2 mile west" of there at

the Magbee Spring.

|

|

Jeter-Boardman

would eventually build several pumping stations and a total

of 45 wells, but there would be trouble ahead for them and

the City. |

This 1898 photo shows

Hillsborough County High School's second home--at 6th Avenue

& Jefferson Street. The photo was taken about 5 years after

the high school had moved out and the building became the

location of only the the grade school.

|

|

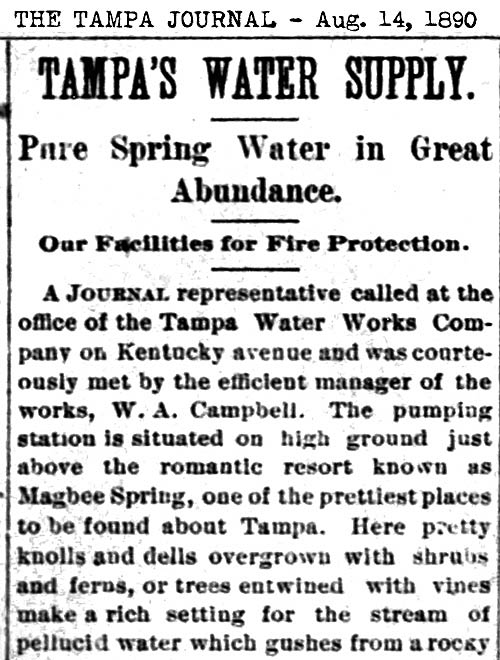

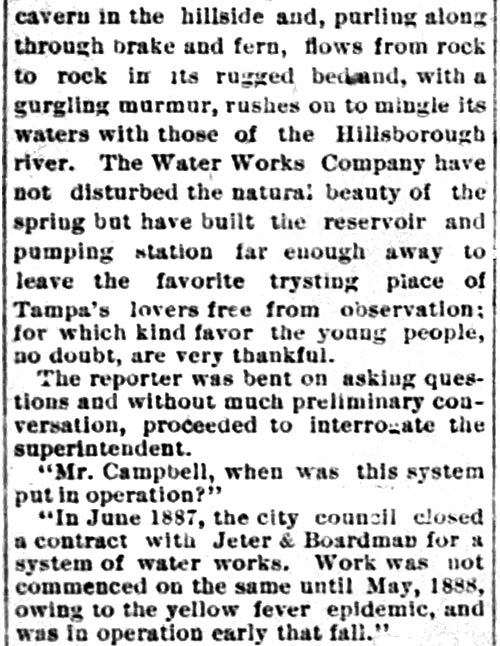

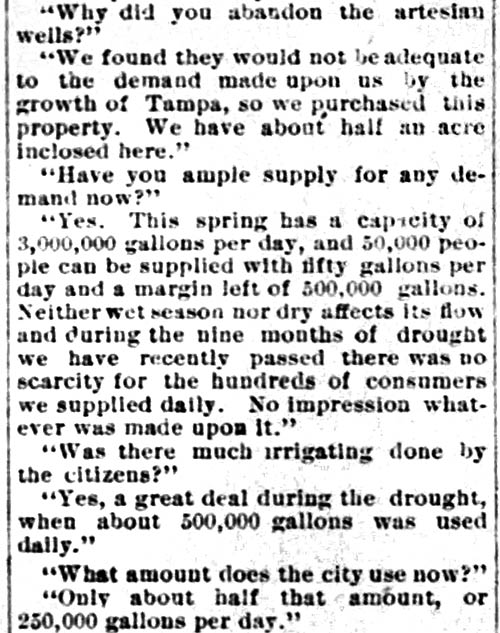

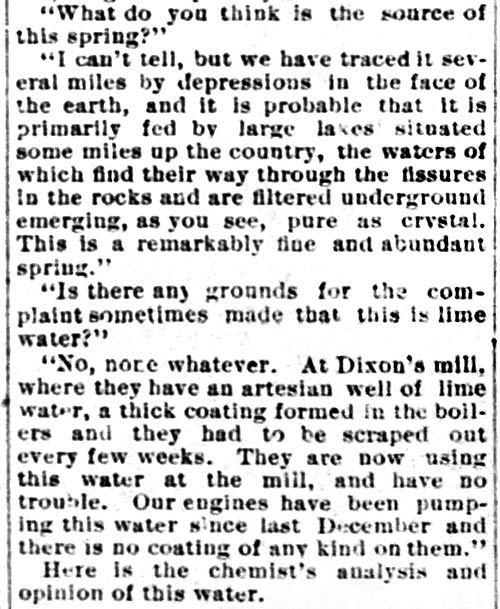

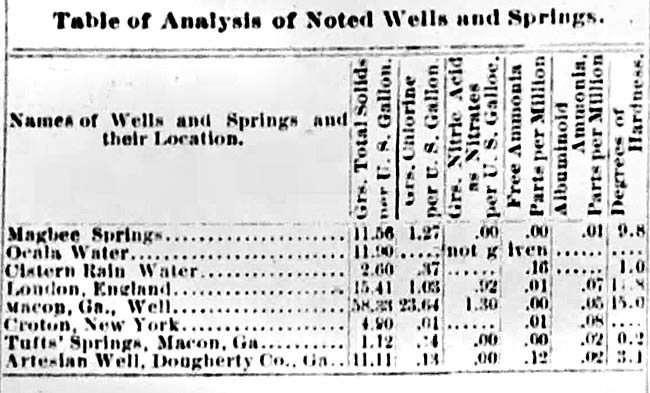

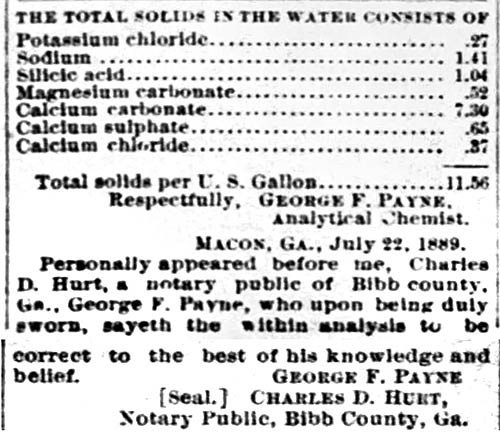

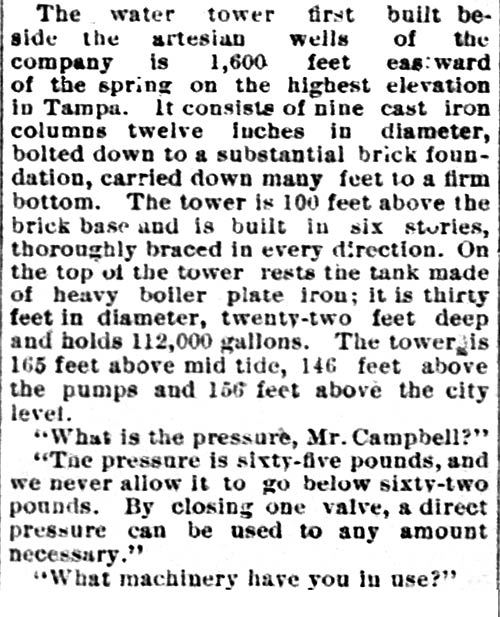

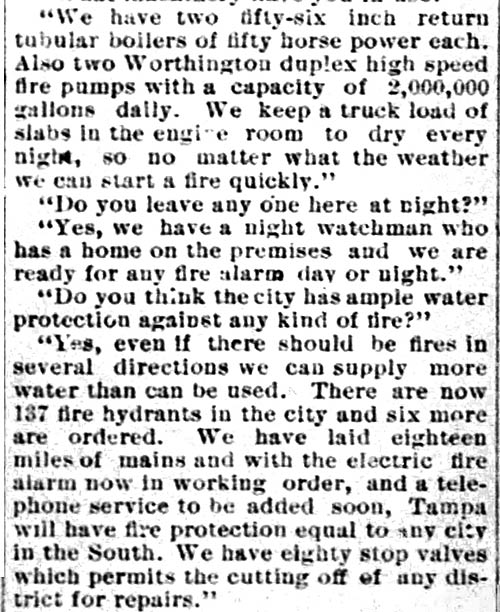

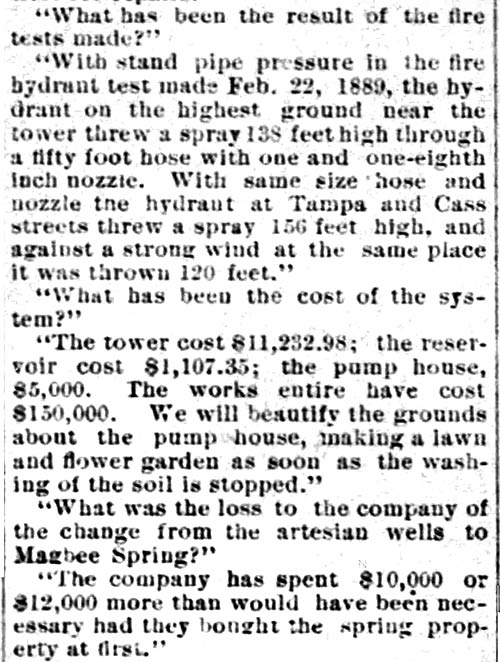

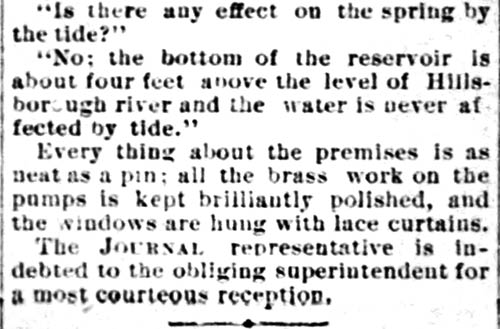

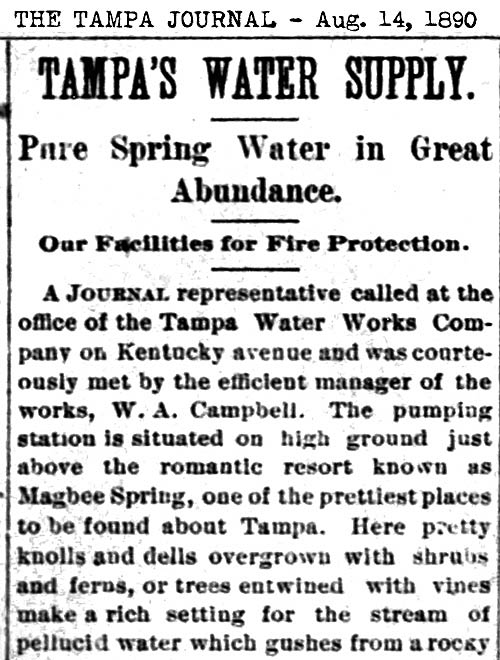

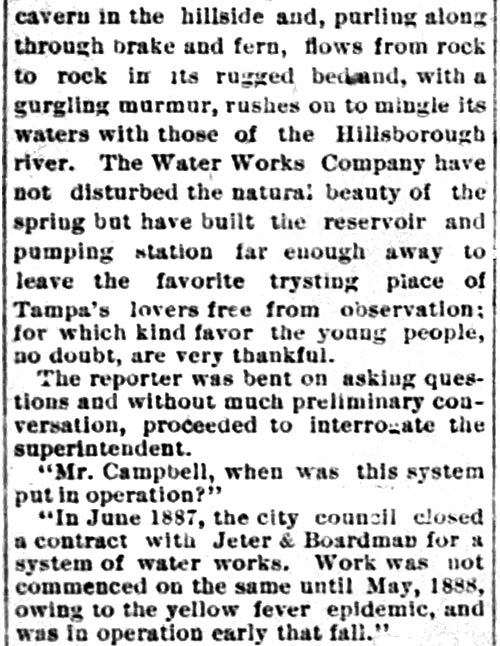

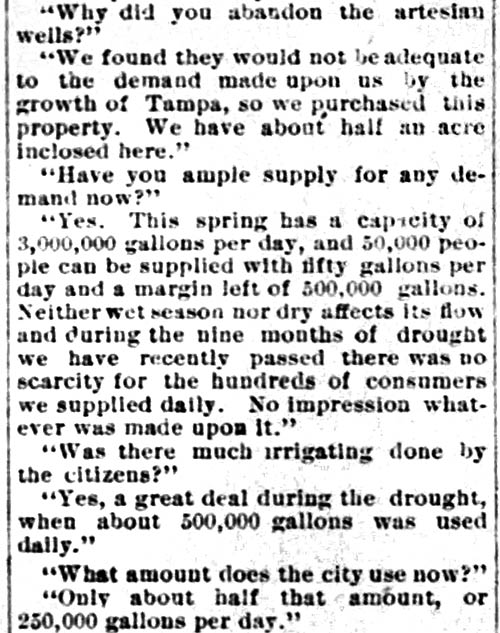

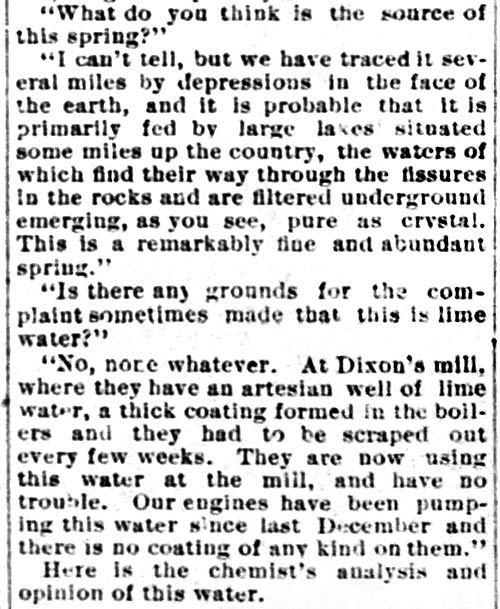

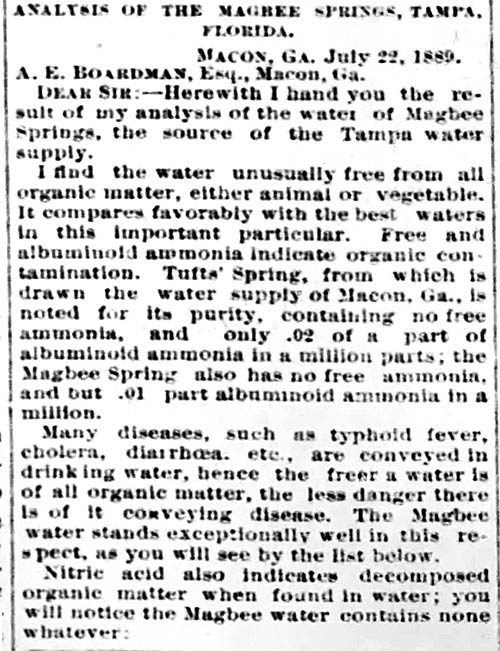

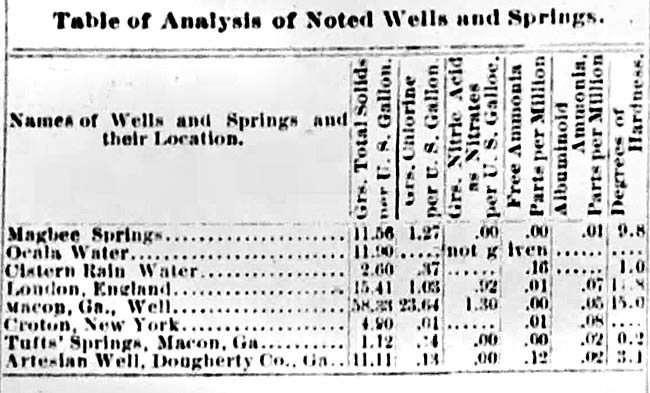

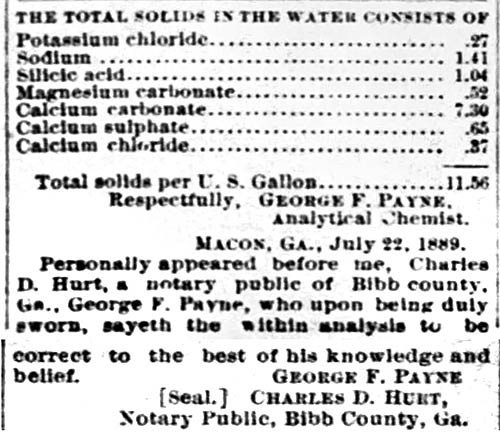

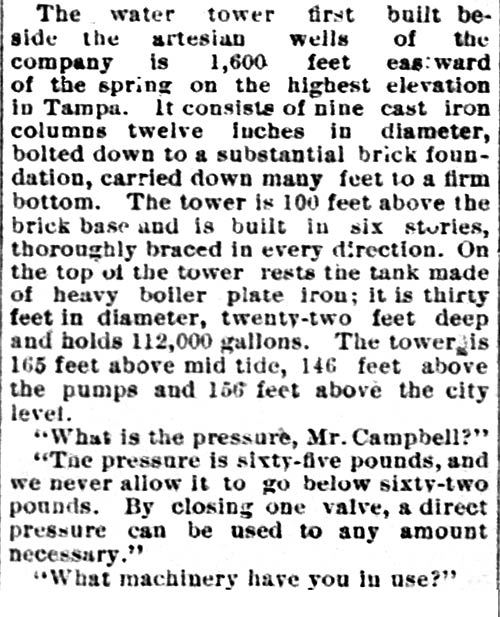

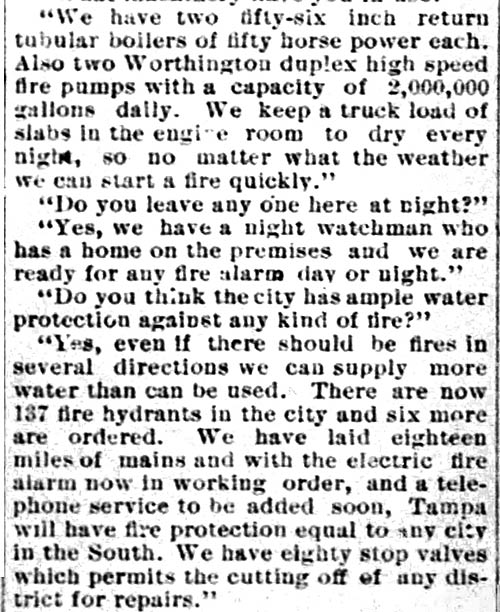

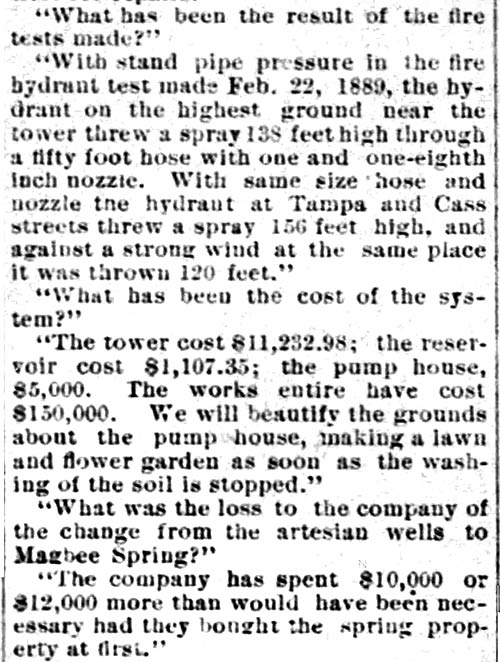

This

1890 article in the Tampa Journal covers the city's

waterworks in every detail. The manager was quite

knowledgeable with specifications and other statistics

concerning the spring.

For

each row, read the left image, then the right image.

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

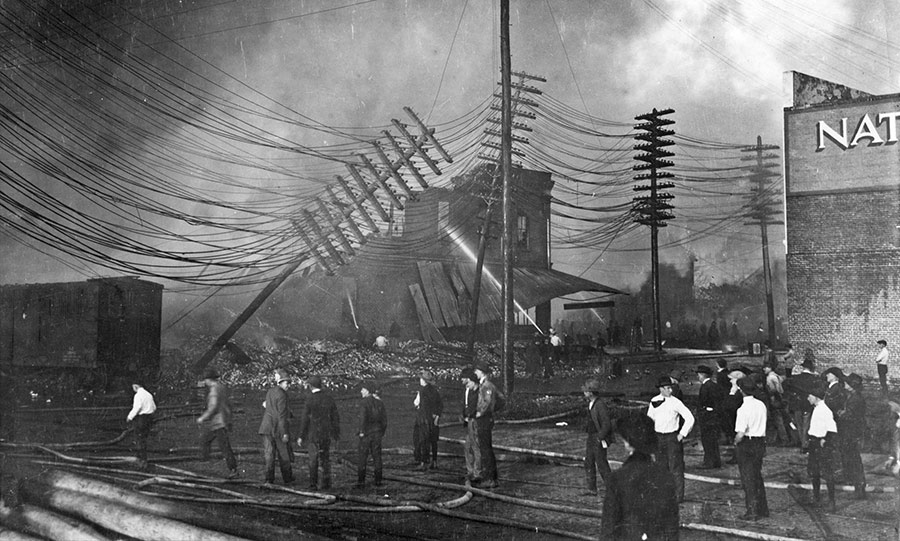

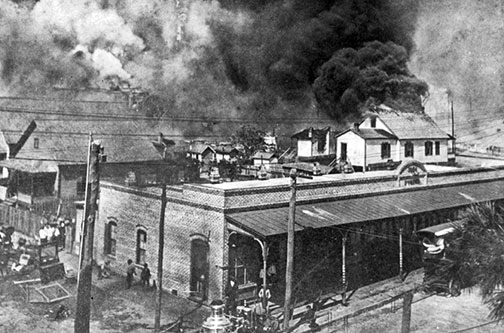

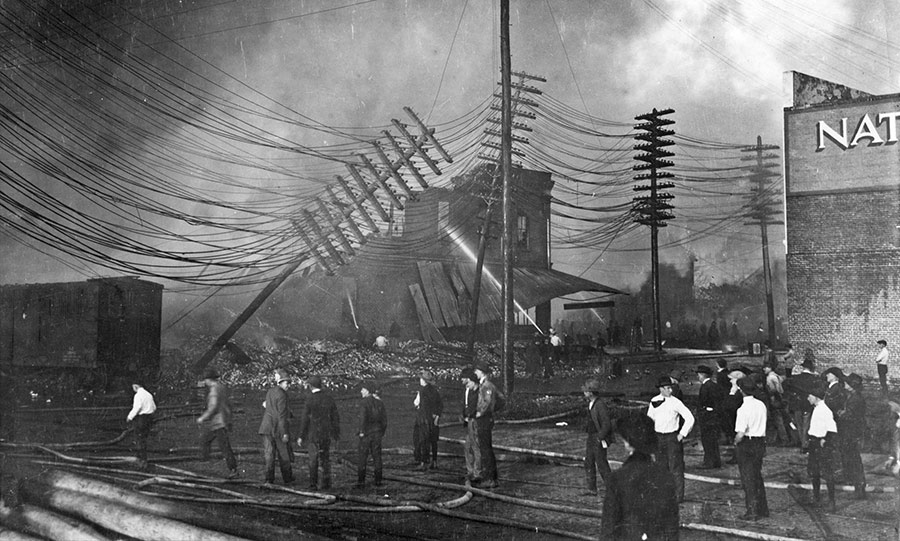

DEVASTATING FIRES

Tampa suffered

a series of disastrous fires during 1894. In addition to

seven homes and three small business places, the Tampa

Lumber Company's plant was completely destroyed on July 27

causing a loss of $40,000. The fires emphasized the

fact that Tampa's volunteer fire department and obsolete

fire fighting equipment were entirely inadequate to provide

proper protection.

|

|

|

Robert Mugge

From the personal collection of his

great-grandson, Robert Mugge. |

By the first decade

of the 1900s, the Jeter Boardman Company and the city were

inundated by complaints about hard water, inadequate expansion

planning, high rates, and demands for improved service.

Damage from several fires was blamed on low water pressure.

A fire on May 23rd, 1905 destroyed a building on the northwest

corner of Franklin and Caro [sic] (Carew) streets, belonging to

noted Tampa businessman, Robert Mugge. Mugge, who was

primarily a liquor dealer, brought suit in the Circuit Court of

Hillsborough County against Tampa Waterworks for failing to

provide adequate fire protection, due to low water pressure,

through a system that was supposed to be "First Class":

"...with a

reservoir capable of holding 100,000 gallons of water,

sufficient to give a pressure on the mains from a hydrant

located at the intersection of Washington and Franklin

streets, and through 100 feet of fire hose and a 1-inch

nozzle, to throw a stream of water vertically to a height or

distance of 50 feet, giving a first-class fire protection..."

The county court

dismissed the suit, in favor of the Tampa Waterworks. But

Mugge took the case all the way to the Supreme Court of Florida,

where the judgment was reversed, "Error to Circuit Court,

Hillsborough County, Joseph B. Wall, Judge.

Read about the details of the case.

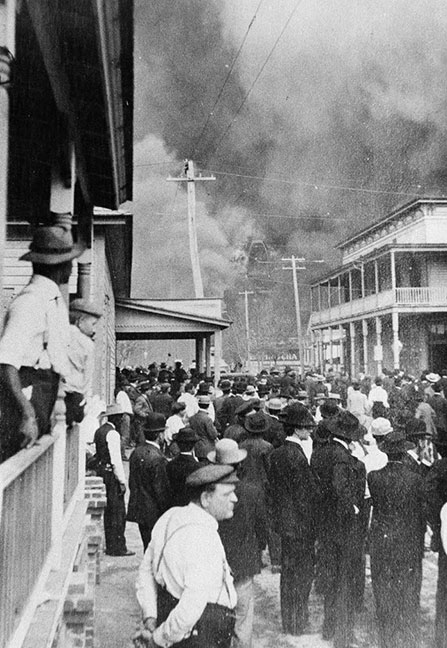

The largest

fire in Tampa's history occurred on March 1, 1908 in Ybor

City. The massive fire was most likely caused by a

carelessly tossed cigarette at the Antonio Diaz

boardinghouse at 1914 12th Ave.

Due to some

confusion in the 1908 blaze, firefighters didn't arrive for

45 minutes. The inferno destroyed 171 homes and 42 business

including five cigar factories over 18 1/2 blocks. Losses

from the 1908 fire exceeded $1 million, half of the losses

were covered by insurance. Firefighters were hampered by low

water pressure from the Tampa Waterworks. This problem

became an issue in the aftermath, with critics questioning

whether the private Tampa Waterworks utility favored its

other customers at the expense of Ybor City. It was

suspected that the waterworks had cut the water pressure

because they felt they couldn't meet the demands of its

paying customers.

Many

residents who lost their homes and or their jobs, relocated

to Key West to work in the cigar factories there.

Ironically, many had just left Key West to relocate in

Tampa.

This history of Tampa's water supply continues further down

below at the

MAGBEE SPRING after the

following sections on the the Ybor Ice Works, the Florida

Brewery at the Government Spring, and the Ybor "No Name" Spring.

|

|

THE YBOR ICE WORKS AND THE FLORIDA BREWERY AT GOVERNMENT

SPRING

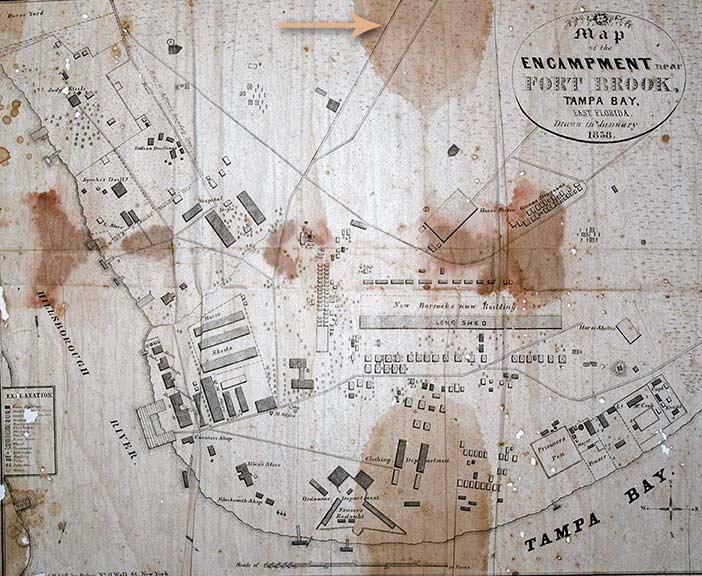

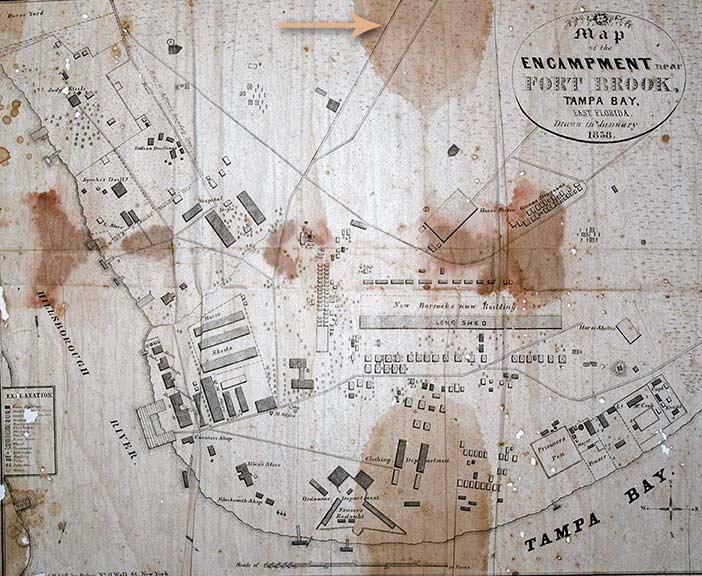

This 1852 map

of Fort Brooke from the National Archives clearly shows the

location of the Government Spring. Mouse over it to

see it larger.

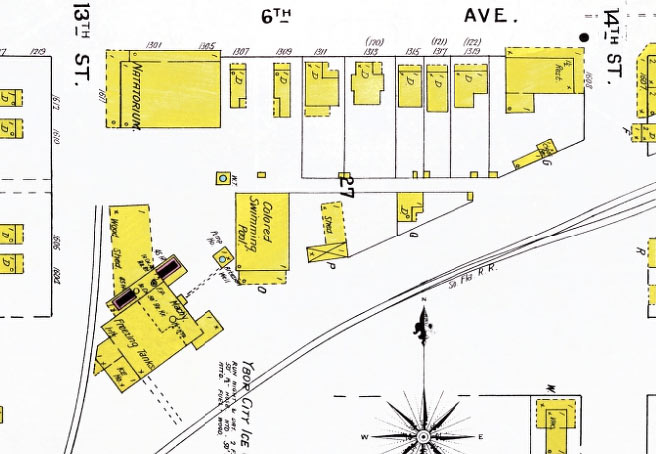

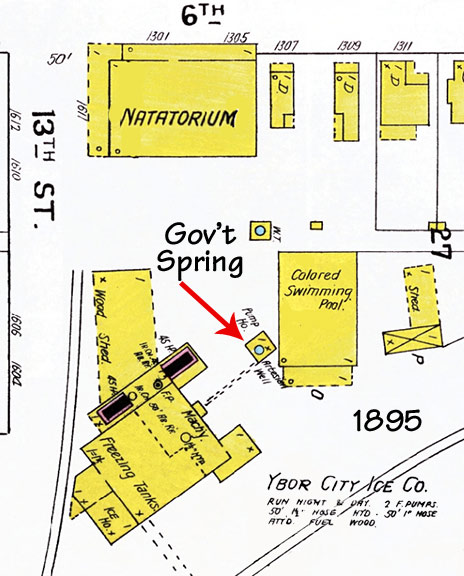

In 1894, the Ybor City Ice Works built two natatoriums (swimming

pools) at the Government spring - one for whites and one for

blacks. The pools were supplied with 10,000 gallons of spring

water per hour.

|

|

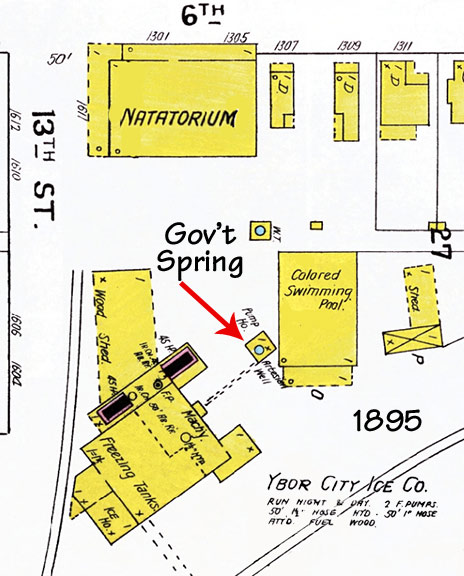

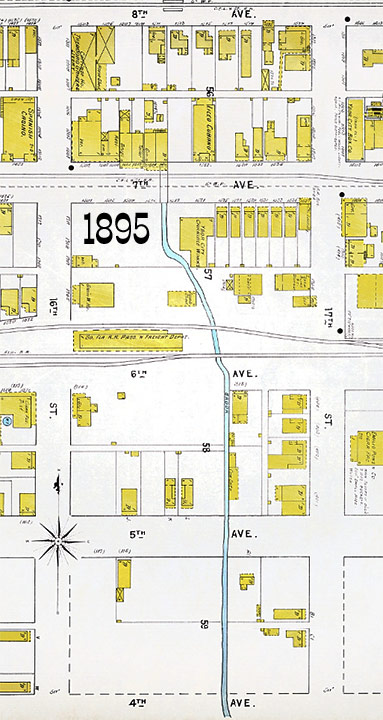

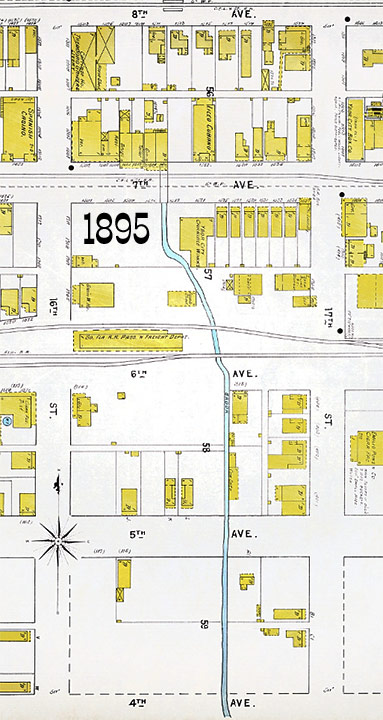

These 1895 maps show the Ybor City Ice Co. with the newly

added swimming pools, and the location of the Government

Spring (label and arrow added to the map) in a pump house

and marked "Artesian well."

Notice that the ice factory was a wood frame structure

(yellow.)

Sanborn Map

Collection at the University of Florida Digital Collection |

|

| |

|

|

|

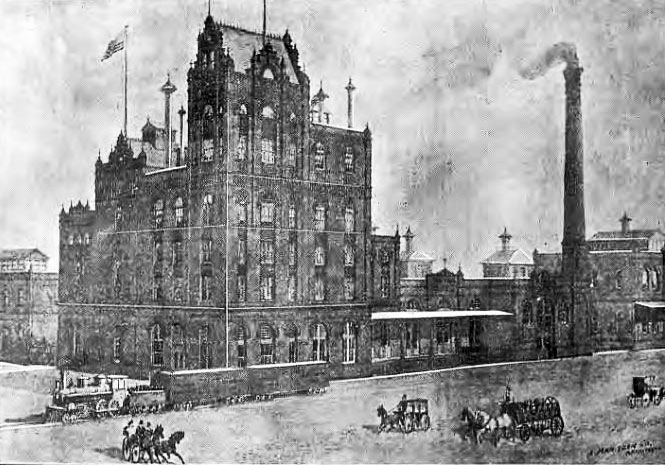

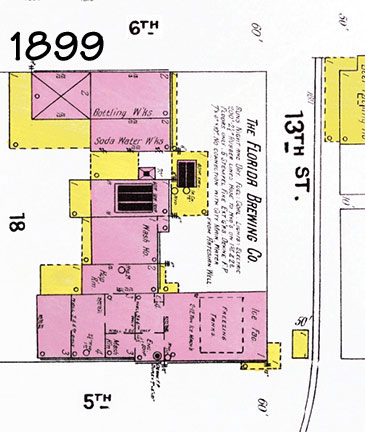

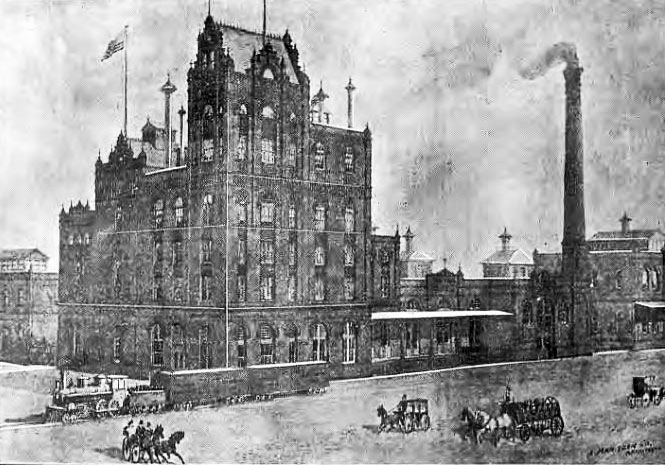

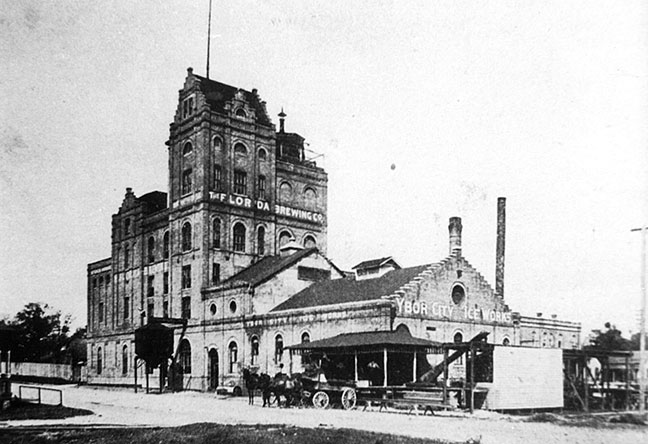

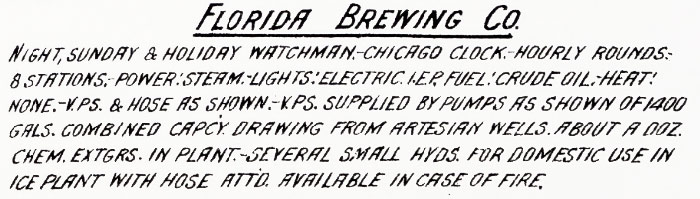

In 1896, with a capital stock of two hundred thousand dollars,

Florida Brewing company was organized by Ybor City cigar

industrialist and entrepreneur Eduardo Manara (who also organized

the Exchange Bank of Tampa in 1894), E. W. Codington and Hugo

Schwab.. The brewery building’s design

was based on the plans of the Castle Brewery in Johannesburg,

South Africa. In addition, Manara underwrote the formation of the

Tampa Gas Company which became Peoples Gas.

The two acre site chosen, at 5th Avenue and 13th Street in Ybor

City, was near to the Government Spring on the east side of 13th

St. across from the ice factory.

At this site, Indians had performed sacred rituals, generals had

planned strategies for the Seminole Indian War, men were hanged

there, and it even had served as a swimming and health resort.

|

|

Factory of the Florida Brewing Company at 1223 5th Avenue and

13th Street, copied from Tampa Tribune Midwinter Edition 1900:

Tampa, Fla.

Burgert Brothers photo from the HCPLC

|

|

The pure spring water was a major influence in the purported

excellent taste of the brewery's product. The site was also

important in that it was next to the railroad which provided

excellent shipping capabilities. |

|

Image courtesy of the Swope Rodante law firm which now occupies

this site.

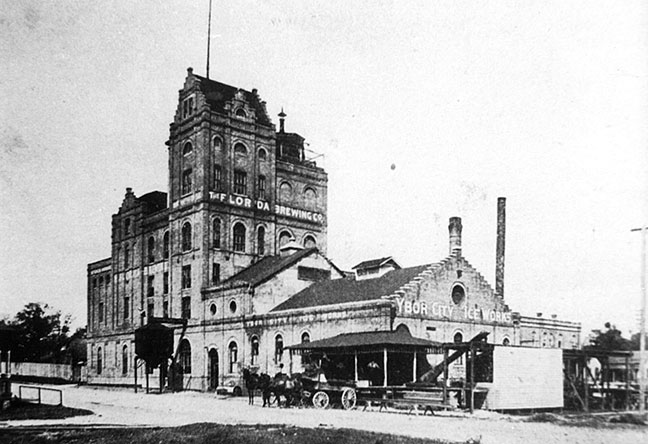

The Ybor City Ice Works seen in these turn-of-the-century photos

is not the original wood frame structure started by Snodgrass in

1884. These photos show this ice works building was part of the

new brewery, made of brick or block, entirely on the west side of

13th St (the face with the ice works signage) and physically

oriented in line with the brewery, parallel and perpendicular to

the street grid.

The satellite image below shows the buildings of the 1895 map

overlaid on the current area. The site of the pump house for the

Government spring is now located near to and under the edge of a

parking lot on the east side of the new 13th Street, about 140

feet northeast of today's intersection of 5th Avenue and the

streetcar tracks.

Also shown is the Swope Rodante law firm in the old brewery

outlined in red. The site of the original 1884 ice factory

is under the blue arrow.

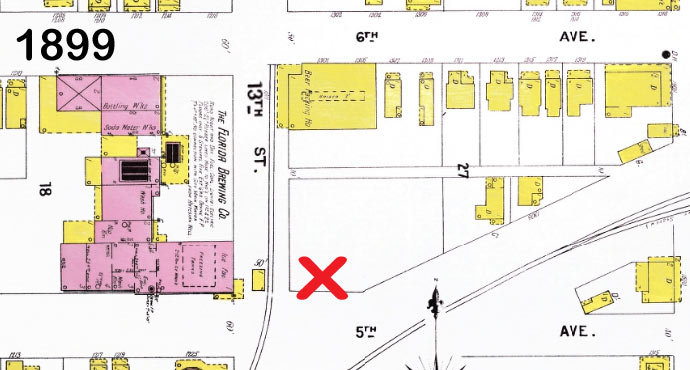

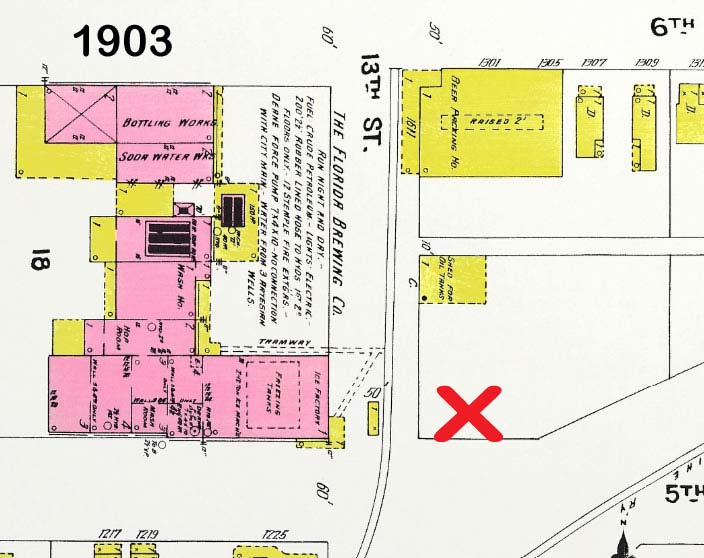

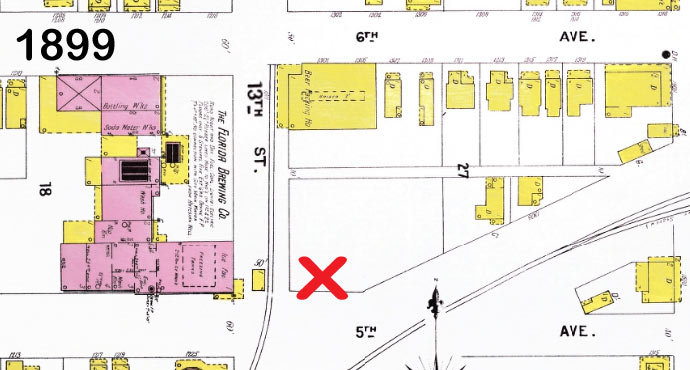

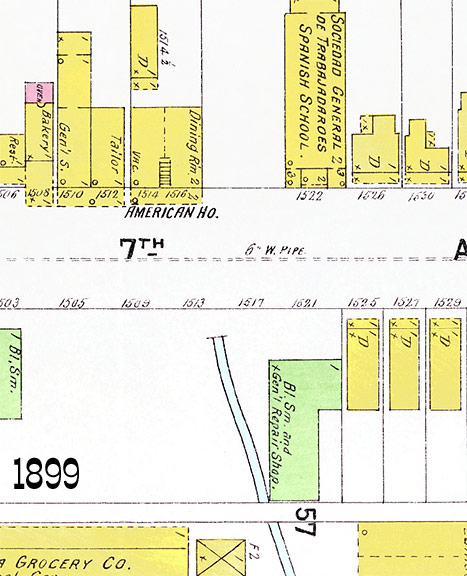

Sometime

between 1895 and 1899, the old wood frame ice factory and the

pools were removed. The "natatorium" became the site of a

beer packing facility. The red X shows where the ice factory

was.

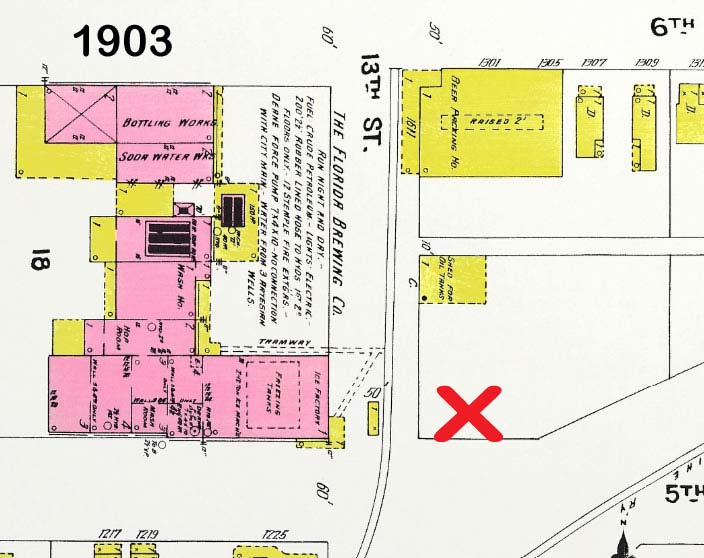

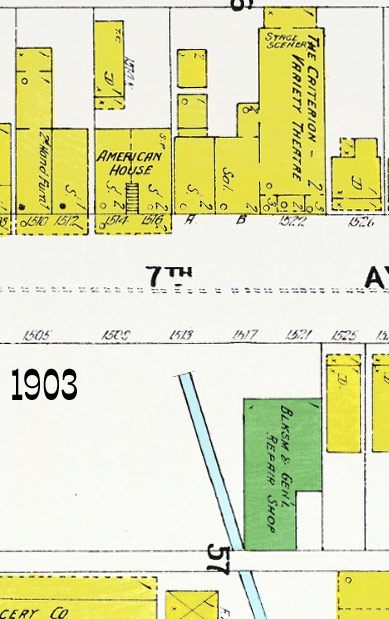

On the 1903 close up below, You can see the ice factory operations

of the new brewery were carried on in the southeast area of the

building at 13th St. and 5th Ave. Notice the train tracks

that came up from the south on 13th St. and between the

brewery and former site of the ice factory.

|

|

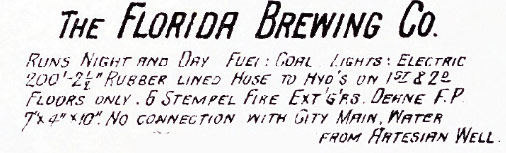

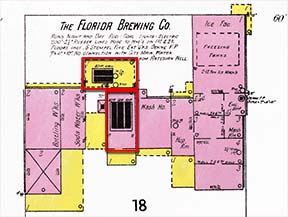

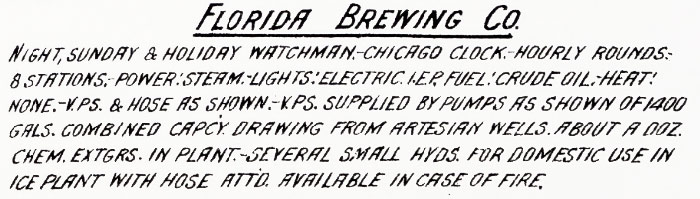

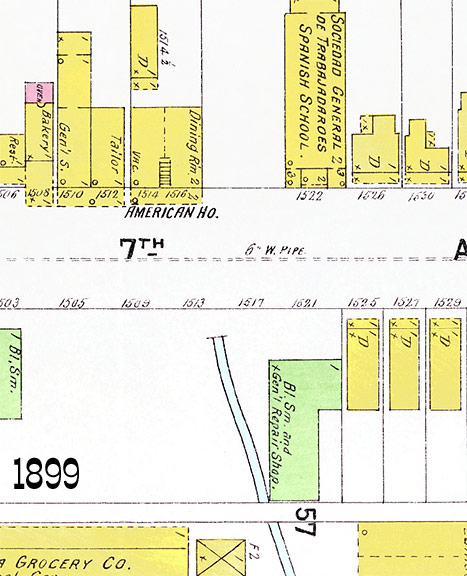

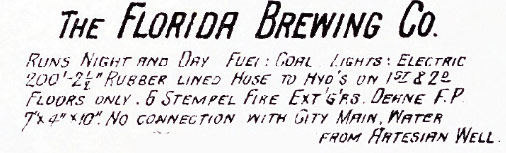

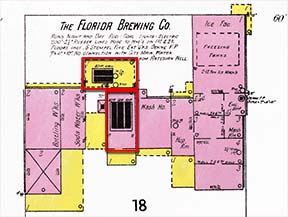

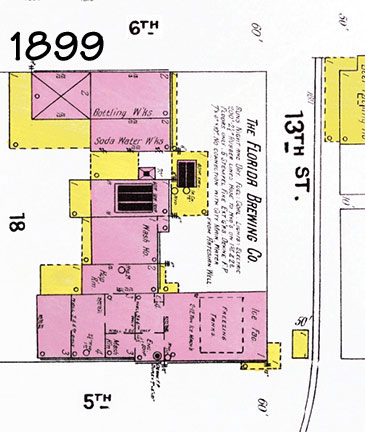

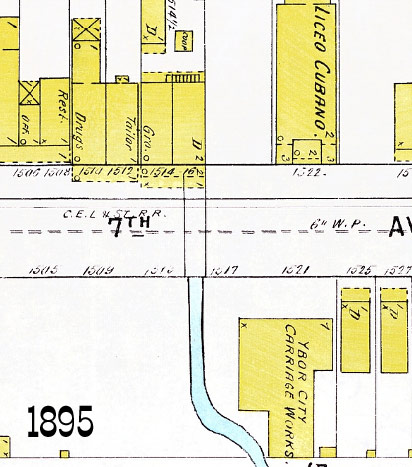

The

1899 map doesn't show the location of the Government spring

but the description of the brewery states "No connection

with City main, water from artesian well." The

1899 map doesn't show the location of the Government spring

but the description of the brewery states "No connection

with City main, water from artesian well."

This sheet (18) of the map was drawn with north to the left,

so the image at the right is rotated to view with north to

the top. Click the image at left to see a larger

layout in the original orientation.

|

|

|

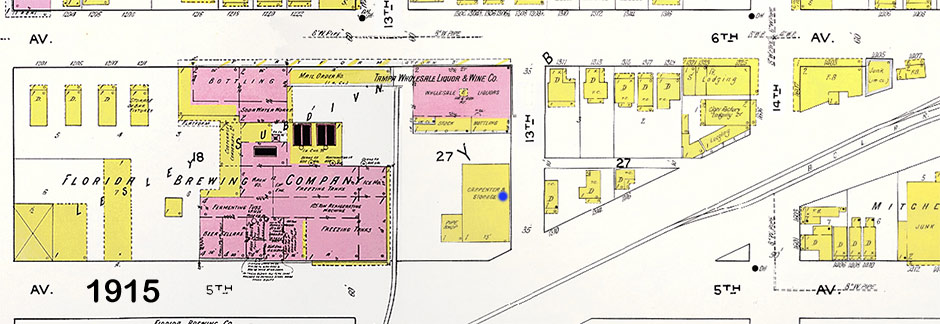

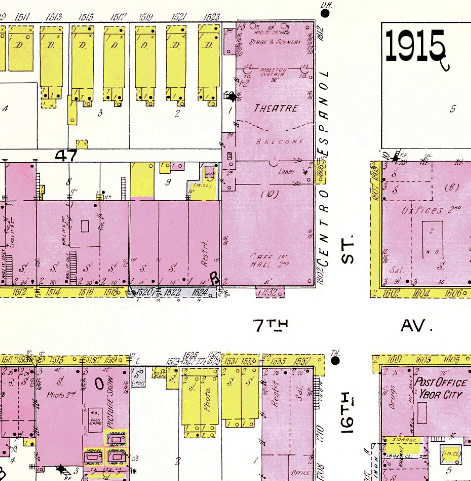

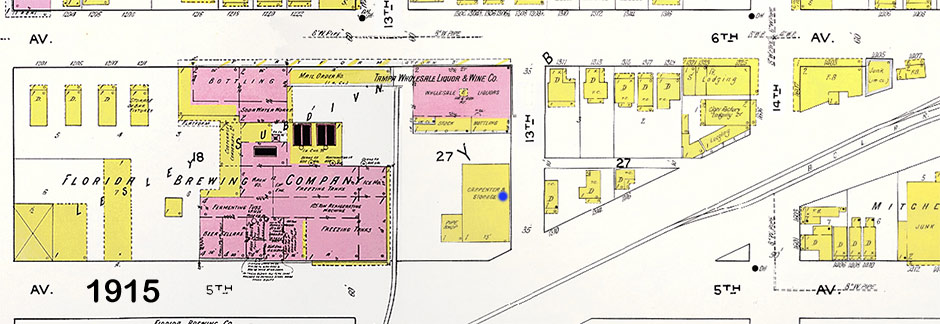

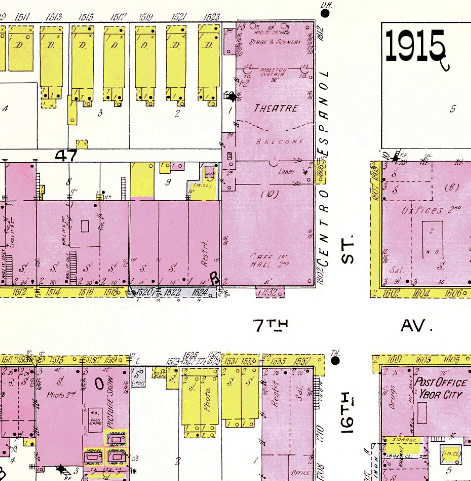

The 1915 map below shows how 13th Street was shifted from

its original location at the tracks between the new brewery

and the old ice factory, at some time between 1903 and 1915.

The beer packing house now has become Tampa Wholesale Liquor

& Wine Co., a brick building. The blue dot indicates

the general area of the former artesian well pump house

originally used by the old ice factory. Now in 1915

this area is a wooden carpenter & storage building.

|

|

Present view of

former site of the original ice factory and Government

Spring artesian well.

Place your cursor on the image to overlay labels

The street runoff water drain may have been placed to use

the same drain as the spring.

|

THE "NO NAME" SPRING

Colonel

Brooke referred to another spring a short distance from the

Government Spring, but the name of this one is unknown. This

small spring was said to have been at 10th Avenue and 16th

Street. Its waters were visible until the late 1970s to early

1980s at 4th and 5th Avenues as it trickled toward the Ybor

Estuary. Two magnificent buildings, El Centro Español and La

Logia del Aguila de Oro, later known as the Labor Temple, were

erected over the creek fed by this spring. Don Jose Acosta built

his home over the spring’s source. Through the ensuing years the

sidewalk and the street in front of the house continued to sink,

a condition which forced Acosta to reinforce the foundations to

his home with annoying frequency. Colonel

Brooke referred to another spring a short distance from the

Government Spring, but the name of this one is unknown. This

small spring was said to have been at 10th Avenue and 16th

Street. Its waters were visible until the late 1970s to early

1980s at 4th and 5th Avenues as it trickled toward the Ybor

Estuary. Two magnificent buildings, El Centro Español and La

Logia del Aguila de Oro, later known as the Labor Temple, were

erected over the creek fed by this spring. Don Jose Acosta built

his home over the spring’s source. Through the ensuing years the

sidewalk and the street in front of the house continued to sink,

a condition which forced Acosta to reinforce the foundations to

his home with annoying frequency.

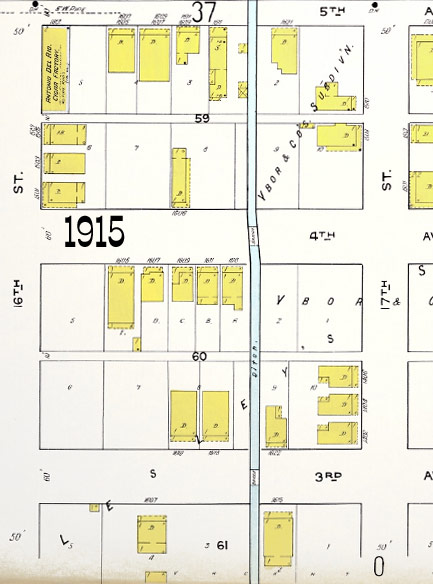

The first Sanborn map to show evidence of this spring is the

1895 map seen at right. There is no indication of a spring

source on any of the section details north of this section, up

to the section that shows 10th Avenue and 16th Street, nor is

there any indication of the creek north of this section.

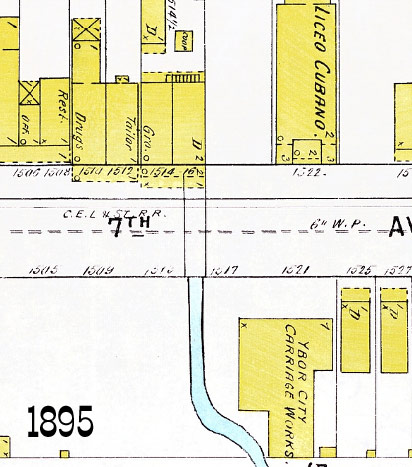

1895 Close up - The creek appears to start under 7th Ave. in

front of a grocery store and dwelling at 1514-1516 7th Ave.

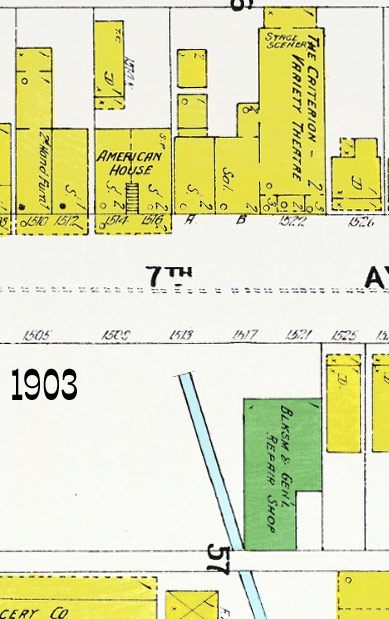

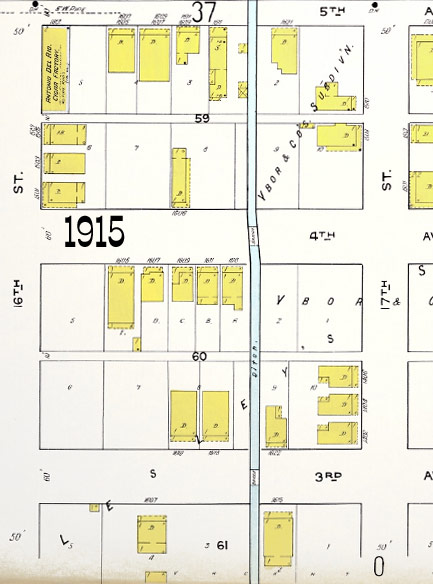

1899 - On the map at right, the creek is again indicated as a

"small stream," starting in the undeveloped property on the

south side of 7th Ave, 1516 7th Ave. is labeled "American

House," apparently a dining room. No other section north

of here show a spring or stream in 1899.

1903 - At left, still indicated as a "small stream" and starting

at the same general area.

1915 - At right, the stream is no longer indicated at 7th Ave.,

nor at 6th Ave. Instead, it appears as a "ditch" at 5th

Ave. southward. 1915 map below.

Neither the stream or ditch appear on the 1931 Sanborn maps.

|

TAMPA WATER WORKS AT MAGBEE SPRING

(continued from "The Beginning of Tampa's

Waterworks" above.)

This spring was named for a local judge named James T. Magbee, who

used to own much of the property in Tampa Heights in this area.

Born in 1820 in Georgia, he came to Tampa in the late 1840s. He

was a lawyer by profession, and in August 1868 Governor Harrison

Reed appointed him judge of the Sixth Circuit Court. As a

Republican official during Reconstruction, he often aroused public

wrath by compelling white men to serve on the same juries with

blacks. Judge Magbee resigned his office in 1874 after

impeachment proceedings for various charges were brought against

him in the Florida Legislature.

Read more about Magbee and his escapades.

The Jeter-Boardman

Waterworks Company also made use of the Magbee Spring at Highland

Ave and Henderson St.

|

|

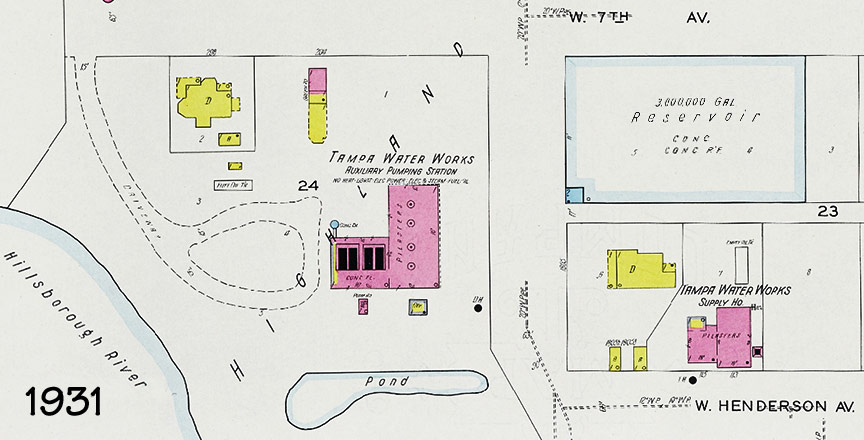

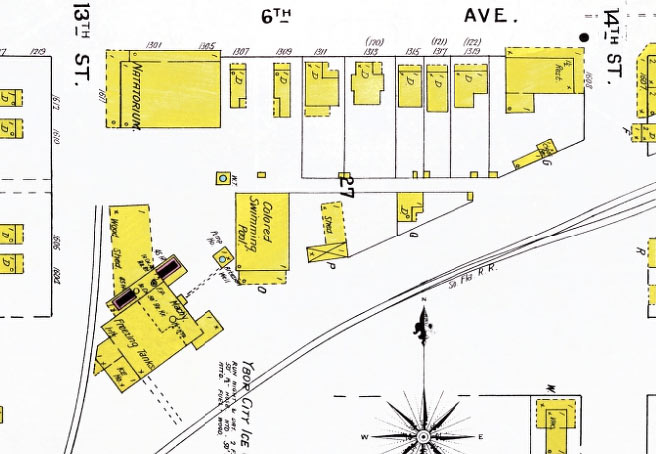

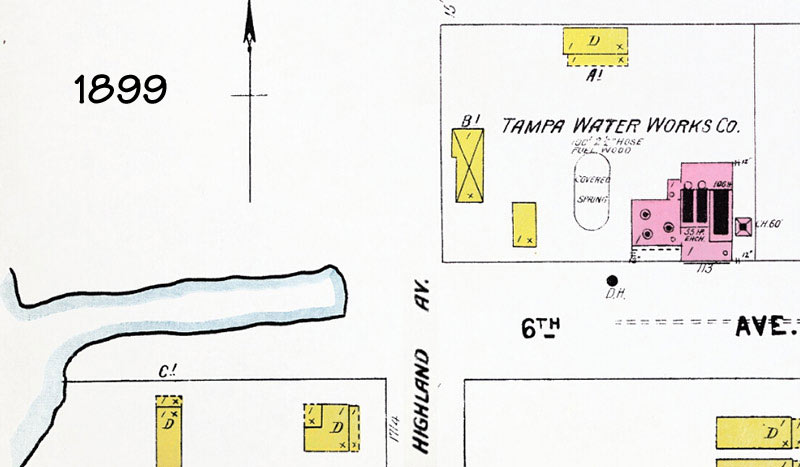

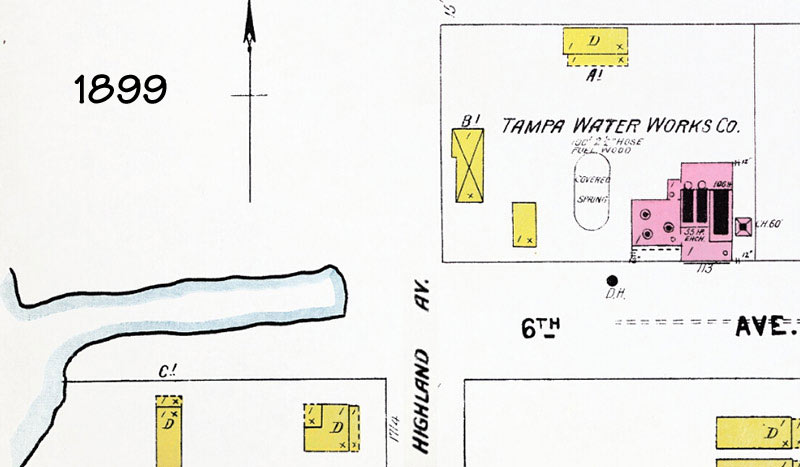

This 1899 map shows the City of Tampa's second pumping

station which was located 1/2 mile west

of Tampa's first pumping station. Since the first

station at Jefferson & Henderson was no longer in use, this

one at the Magbee Spring on Highland and 6th (also known as Henderson Ave.)

became Station #1.

Notice the oval marked "COVERED SPRING" to the left of the

pumping station Apparently, the spring source was on

the east side of Highland Ave. The unmarked inlet from the river at the left was where the Magbee Spring emptied into the river. |

| |

|

|

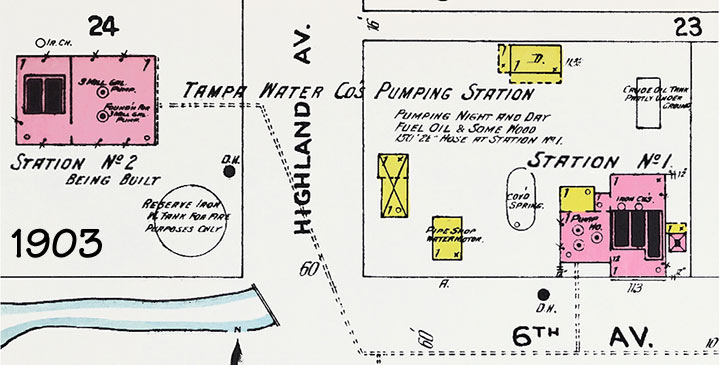

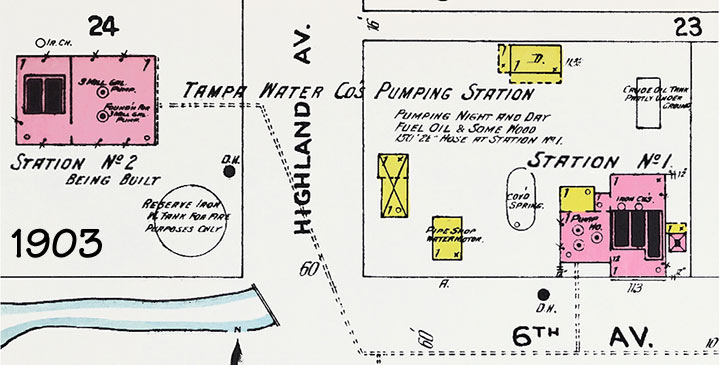

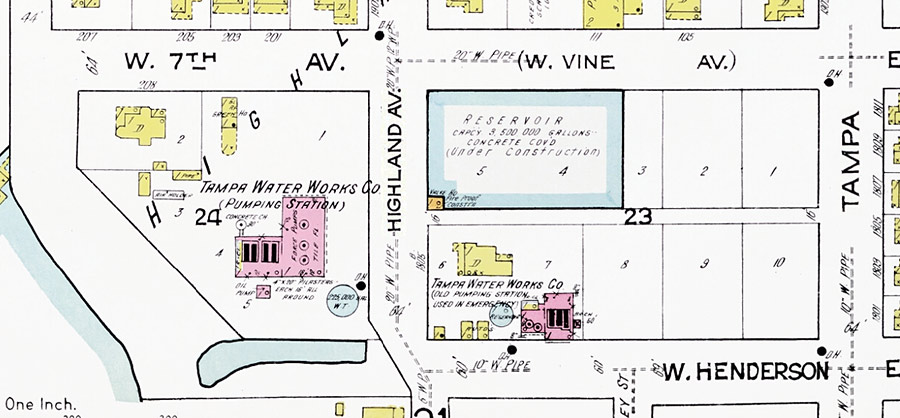

The City of Tampa was very progressive in its construction

of steam powered pumping stations to bring fresh water to

its citizens, as seen on this 1903 map. Construction of

Tampa's third water works (#2) was already in progress,

allowing the City to continue utilizing the water of Magbee

Spring, and increasing capacity to four million

gallons per day over the second pumping station (#1).

|

|

| |

|

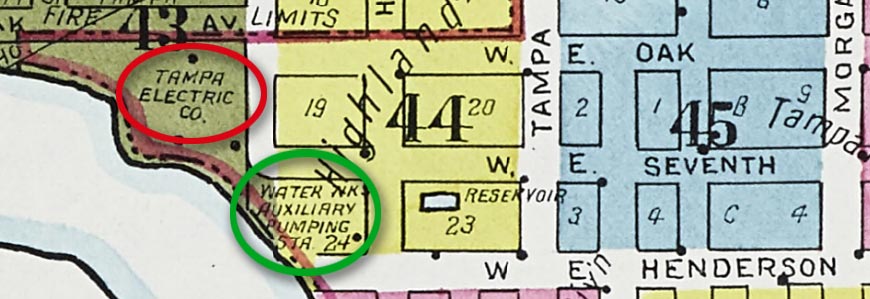

In 1910 the Tampa Electric Streetcar Company built the hub of

Tampa’s streetcar system just northwest of the area and this

beautiful stretch of river quickly filled in with heavy industrial

uses.

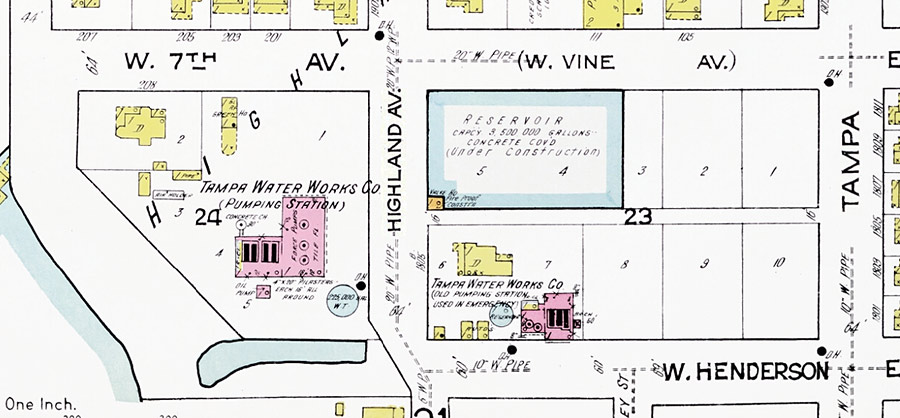

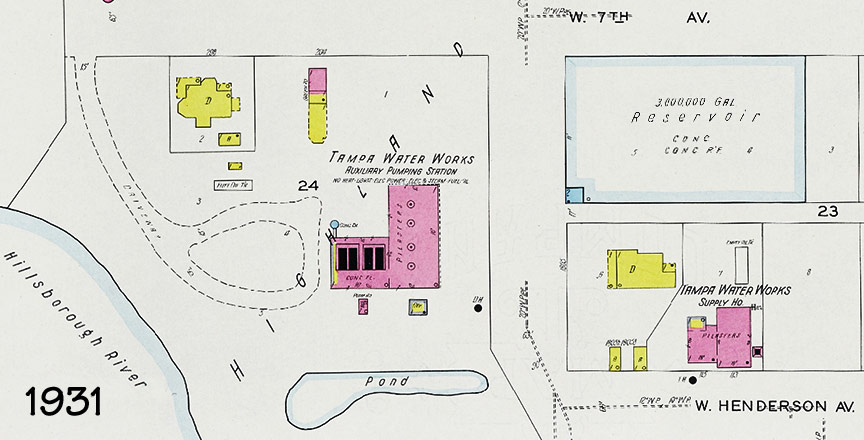

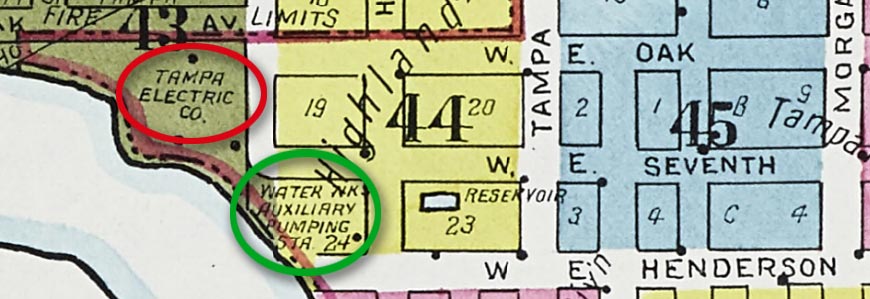

This

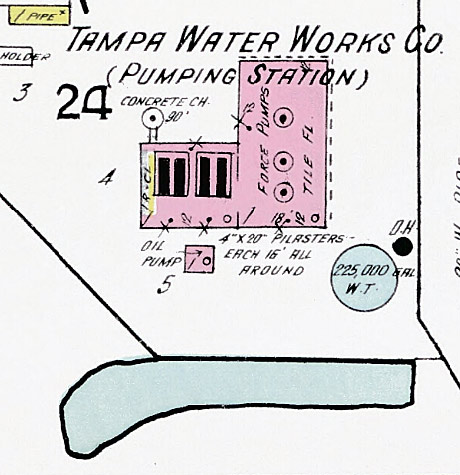

1915 Sanborn map above shows the location of the Tampa Water Works Co. pumping

station in pink on the left with the

spring pool (unlabeled) just below it. Across Highland Ave.

was the old pumping station which was then used in emergencies.

Notice the large 3.5 million gallon, concrete-lined rectangular

reservoir under construction. This

1915 Sanborn map above shows the location of the Tampa Water Works Co. pumping

station in pink on the left with the

spring pool (unlabeled) just below it. Across Highland Ave.

was the old pumping station which was then used in emergencies.

Notice the large 3.5 million gallon, concrete-lined rectangular

reservoir under construction.

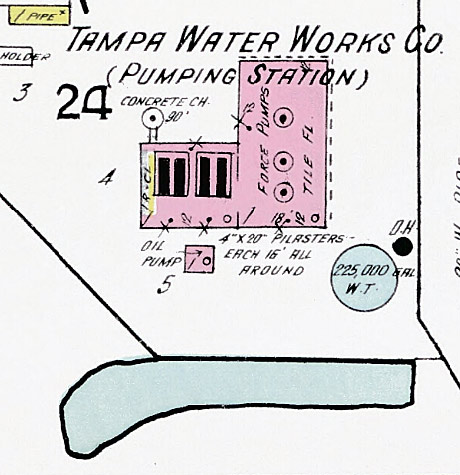

At right, close up from same map above. Notice the small circle with a

dot to the right of "24", a 30-ft. tall concrete chimney which can be

seen in the photo below.

Map images courtesy of the University of Florida

Smathers Library Sanborn Map Collection

The Tampa water works pumping station at 1804 Highland Avenue between

7th Avenue and Henderson Street, 1918.

The small structure to the

left of the main building can be seen on the map close up above; it was

an oil pump house.

Burgert Bros. photo from the digital collection of the

Tampa-Hillsborough County Public Library.

Ornamental landscaping and gravel paths at the Tampa water works pumping

station on 1804 Highland Avenue between 7th Avenue and Henderson Street,

1919.

Burgert Bros. photo from the digital collection of the

Tampa-Hillsborough County Public Library.

|

|

In December of

1919 a devastating fire destroyed much of Tampa's waterfront

along the Hillsborough River in the area of Washington St.

Burgert Bros. photo from the digital collection of the

Tampa-Hillsborough County Public Library.

|

|

1919 Waterfront

Fire -

Photo from USF Digital Collection, Burgert Brothers

(The collection has this photo incorrectly titled "Ybor City

Fire") |

| |

|

In the 1920s, the Magbee spring was surrounded by a lily pond that was a

fashionable spot for Sunday picnics.

Al Severson and Maudie in a rowboat at Tampa Water Works Park,

1925.

Severson

was a photographer for the Burgerts

Burgert Bros. photos from the digital collection of the

Tampa-Hillsborough County Public Library.

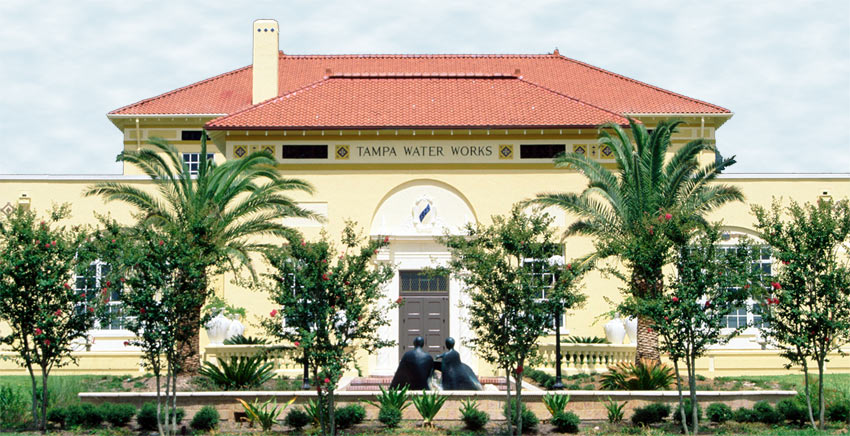

THE

WATERWORKS ON THE HILLSBOROUGH RIVER

Even though the Tampa

Waterworks Company continued to provide services for the entire

length of their contract, in 1922 the city

obtained the services of Nicholas S. Hill, Jr., an engineer from

New York, to evaluate options for the future.

|

|

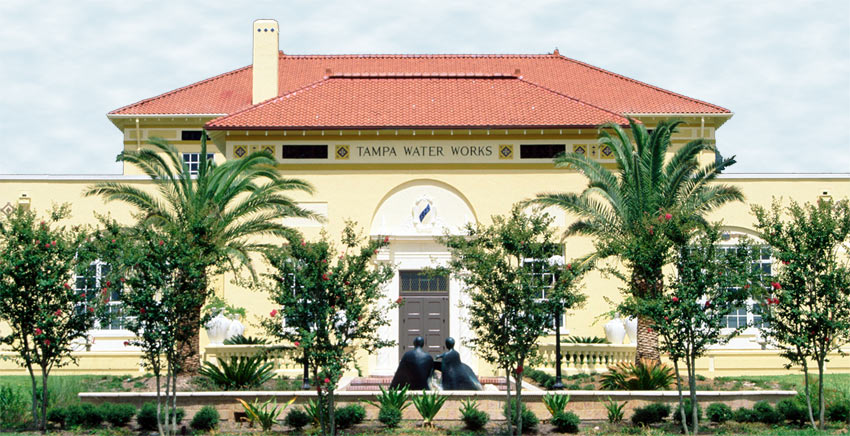

The original

Water Works filter house, completed in 1925, housed the core

of the facility’s treatment process.

Burgert Bros. photo from the digital collection of the

Tampa-Hillsborough County Public Library. |

After studying

the matter for more than a year, Hill recommended that the city

construct a modern filtration plant on the Hillsborough River, to

be situated just upstream of Tampa Electric's power-generating

dam. The construction began in 1924.

Construction of this facility at 30th Street in Sulphur Springs

(the area, not the water source) replaced Tampa's third pumping

station at the Magbee Spring but allowed the City to continue to

utilize its water. It was built at the height of the Florida 1920s

real estate Boom Times in 1925 and reflects the Mediterranean

Revival style associated with the period.

Local Historic Designation:

2004

Architect: Nicholas S. Hills, Jr.

Builder: Gauger-Korsomo

The

building is now part of the David L. Tippin Water Treatment

facility, a 55-acre facility still in full operation. This

facility houses Florida’s only municipally-owned drinking water

laboratory. Today, the plant produces approximately 90% of the

roughly 65 million gallons of water that is consumed per day by

Tampa residents.

Most

of Tampa's drinking water is treated surface water from the

Hillsborough River. The river begins in the Green Swamp and winds

its way through Tampa to Hillsborough Bay. In Tampa's Sulphur

Springs area, the river reaches the Hillsborough River Dam. The

Hillsborough River Reservoir, the stretch of river between the dam

and the 40th Street Bridge, impounds more than 1 billion gallons

of water. The reservoir holds Tampa's primary drinking water

source, which is treated at the adjacent David L. Tippin Water

Treatment Facility. Most

of Tampa's drinking water is treated surface water from the

Hillsborough River. The river begins in the Green Swamp and winds

its way through Tampa to Hillsborough Bay. In Tampa's Sulphur

Springs area, the river reaches the Hillsborough River Dam. The

Hillsborough River Reservoir, the stretch of river between the dam

and the 40th Street Bridge, impounds more than 1 billion gallons

of water. The reservoir holds Tampa's primary drinking water

source, which is treated at the adjacent David L. Tippin Water

Treatment Facility.

Treating Tampa's Water at TampaGov.net

The

yellow rectangle at left marks the original waterworks filter

house. The red rectangle marks the original pumping station

below.

|

Today, the

original structure remains the core of a modern, high-tech

water production facility that ensures a safe, reliable

drinking water supply for Tampa residents, visitors and

businesses.

TampaGov.net - Our Water Plant |

|

To continue the

history of the dam, see the video below, narrated by Jack Harris,

starting at 17:10 time. Some of the above history of the

Jeter-Boardman Waterworks in Tampa comes from this City of Tampa

video.

BACK TO THE MAGBEE SPRING WATERWORKS

By 1931 the original pumping station #1 at Magbee Spring had become a supply house for

storage.

Elise Frank School of Art students painting at Water Works Park, 1804

Highland Avenue, 1948.

Burgert Bros. photo from the digital collection of the

Tampa-Hillsborough County Public Library.

A fish processing plant, a shipyard, a dredging operation and the

City of Tampa’s Police Station and Maintenance Facility in the

1960s ultimately choked off access to the Hillsborough River for

the surrounding neighborhoods and filled in the natural spring

run.

The Magbee Spring at the Tampa

waterworks site, 1950s

Photo from University of South Florida Robertson & Fresh

collection

The

city had turned to other water sources and the

neighborhood languished. By the 1970s, vagrants were living in the

park and bathing in the spring, so the city fenced and padlocked

the property.

| The Dam Story: the story

of the Hillsborough River Dam

City of Tampa video hosted by

Jack Harris

Tampa's waterworks history

starts at 14:56. |

|

| |

|

MAGBEE SPRING RENAMED ULELE

In

February of 2002, after several years of political maneuvering,

the Tampa Water Works building at 1805 N. Highland Ave. was

designated a historically significant city landmark, saving it

from demolition and qualifying the structure for rebuilding

grants.

Photo from City of Tampa Government website - Local Historic

Landmarks, Tampa

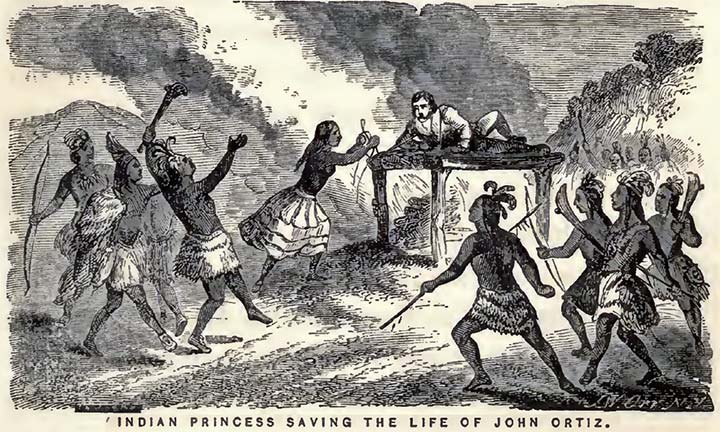

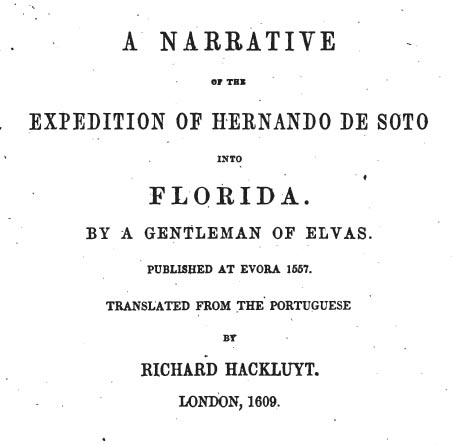

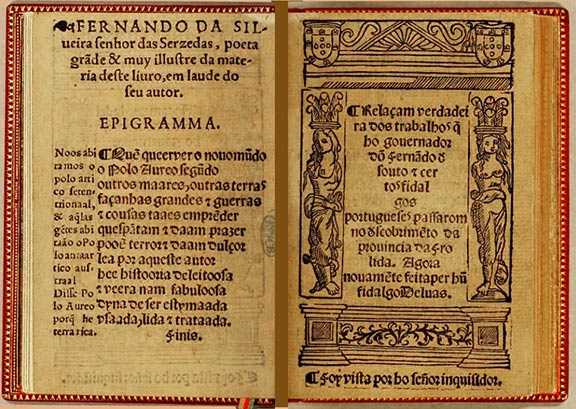

| In November of

2006, Chris Longo, a 17-year-old Plant High School senior

presented research on the Ulele/Ortiz history and Judge James T. Magbee,

namesake of the spring at the water works, for his Eagle Scout designation

project. His goal was to

get the name of the Magbee Spring changed to Ulele Spring in honor

of the daughter of the Timucuan tribal chief who lived during the

1500s.

“Ulele is a name people are becoming familiar with,” said

Judge Chris Altenbernd of the 2nd District Court of

Appeal, who inspired Chris Longo to lobby the city to name

the spring in Ulele's honor. “It's a fun part of Tampa's

history.”

As with the legend of the swashbuckling Jose Gaspar,

historians differ on how much of Ulele's story is fact, how

much is fiction and whether she existed at all. “It

seems clear this is a story passed on, possibly through many

people, before it was written down,” Altenbernd said. “So

who knows?” |

|

The spring’s first namesake was not as dignified as the

Ulele story: James T. Magbee, a circuit judge who presided

from 1868 until his forced resignation in 1875. Magbee owned

the spring property and adjacent land, but the judge had a reputation for public

drunkenness and other less-than-honorable deeds.

.

|

|

|

|

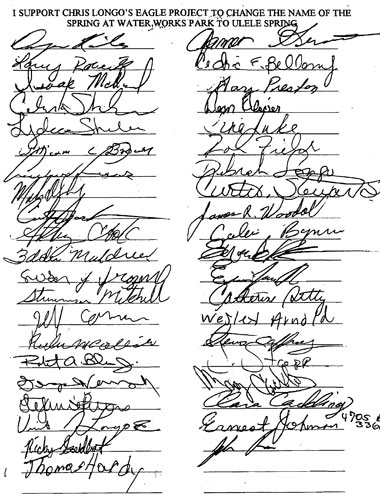

Images are excerpts from Chris's

reports.

“Should the

alcoholic judge have his name remain on the lifeblood of Tampa’s

first water source?”

Longo wrote to the Tampa City Council.

“Changing

the name from Magbee Spring to Ulele Spring would put dignity back

into the spring and would also establish the Spanish-American

Indian connection in early America.”

The city council

agreed and voted to rename the spring.

|

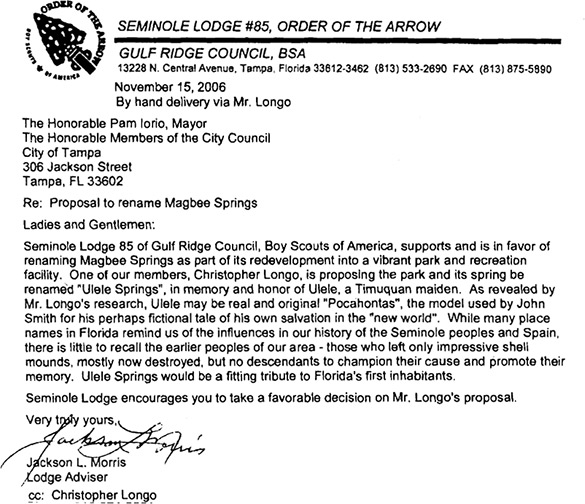

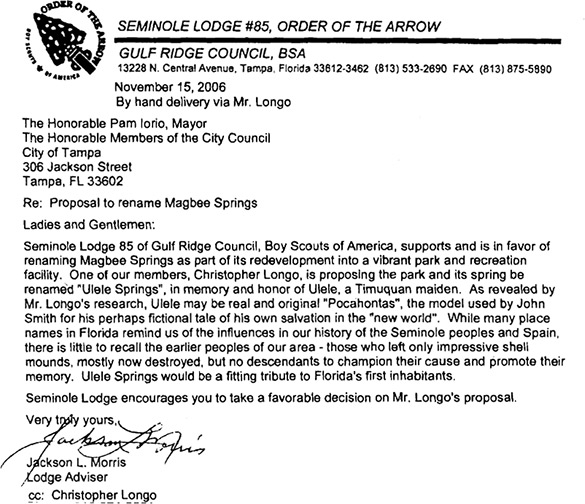

Nov. 15, 2006 letter from Boy Scouts of America Seminole

Lodge #85, Order of the Arrow Lodge Adviser Jackson L.

Morris to Mayor Pam Iorio urging her to take a

favorable decision on Chris Longo's appeal.

"...While many place names in Florida remind us of the

influences of our history of the Seminole peoples and Spain,

there is little to recall the earlier peoples of our

area--those who left only impressive shell mounds, mostly

now destroyed, but no descendants to champion their cause

and promote their memory. Ulele Springs would be a

fitting tribute to Florida's first inhabitants."

Seminole Lodge #85 Website

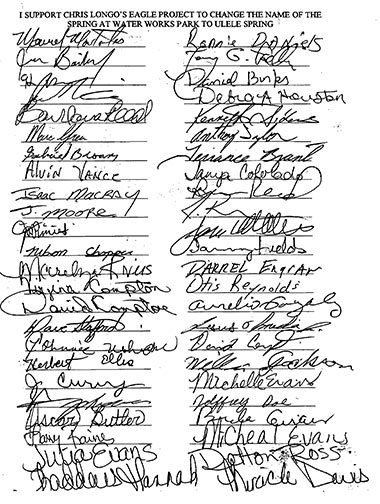

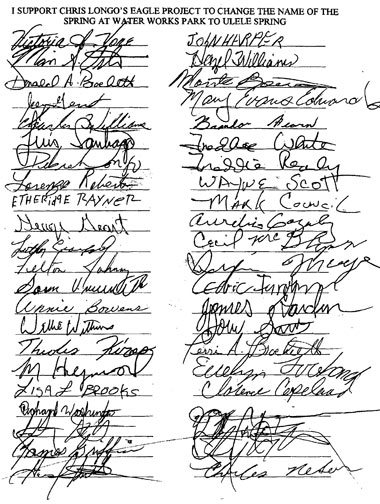

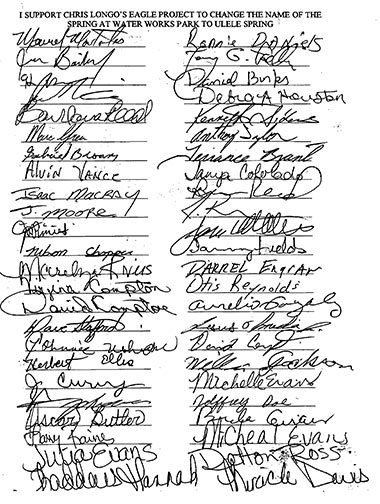

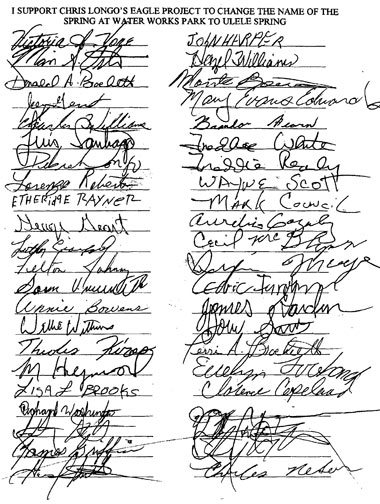

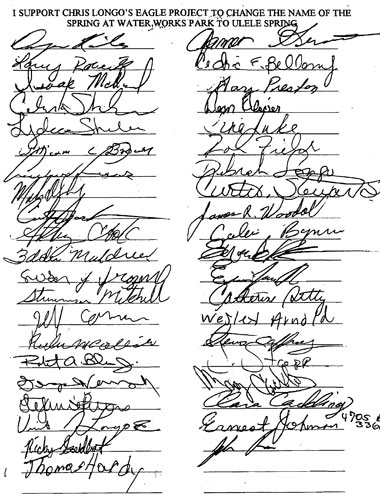

133 signatures

supporting Chris's project

|

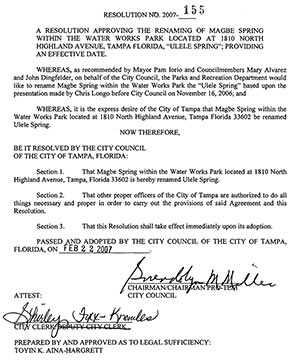

On Feb. 22, 2007,

Tampa City Council changed the name of the spring from

Magbee to Ulele Springs with the passing of this resolution,

#2007-155, as

proposed by Chris Longo's petition.

Click image to see

it larger.

More about Judge Magbee here at TampaPix

See a video and read more about Ulele Restaurant at the TBO.com article

by Jeff Houck.

Here's more about

Christopher Longo. He is a very talented young man!

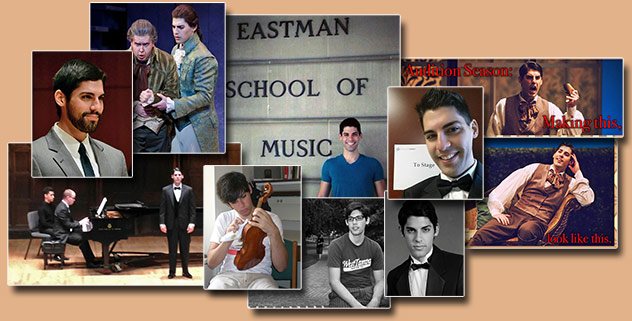

Christopher Longo is an American tenor from Tampa, Florida, where

he originally pursued a career in violin before switching to voice

studies at Florida State University. Along with this season’s

chorus work, he will sing in a number of concerts at the Sarasota

Opera House and other venues performing in ensemble scenes as an

Apprentice Artist.

Most recently, he

was a

Bonfils-Stanton Apprentice Artist with Central City Opera in

Colorado, where he performed as Alfredo in Verdi’s La Traviata

and covered the role of Padre in Wasserman’s Man of La Mancha.

With Eastman Opera Theatre he performed in the award-winning

production of Poulenc’s Dialogues of the Carmelites as

Chevalier de la Force, and covered George in Rorem’s Our Town.

Of his Chevalier portrayal, the Democrat and Chronicle

recognized that his "unperturbed purity of tone and precise pitch

placement sharpened a strong dramatic presence.”

Mr. Longo holds a Master of Music degree in Performance and

Literature for Voice from the Eastman School of Music, and a

Bachelor of Music degree in Voice Performance from Florida State

University. At FSU his roles included The Prince in Rusalka,

Nemorino in L'elisir d'amore, Frederick in Pirates of Penzance,

Herr Vogelsang in Der Schauspieldirektor, and Orphée in

Orphée aux enfers. His upcoming engagements include singing in

the chorus and covering Alfredo in Verdi’s La Traviata in

June 2018 for St. Petersburg Opera.

Bravissimo,

Christopher, bravissimo!

RECREATING THE SPRING

and REVIVING THE WATER WORKS BUILDING AS ULELE RESTAURANT

Tom Ries, President of the nonprofit

Ecosphere Restoration Institute, would work diligently for

years to recreate a natural landscape for the spring to enter the

river.

When Ulele Spring was "re-discovered" next to the Tampa's old

Water Works in 2006, Tom Ries of the Ecosphere Restoration

Institute had to see it for himself. Hacking through dense growth

that had gone unchecked for years, Tom discovered the spring boil

just feet off North Highland Avenue near the heavy traffic of

I-275. The spring dropped into a lower pool full of lily pads that

surrounded a small island of palm trees and then the water

disappeared. Marching in a straight line from where the run ended

to the Hillsborough River, Tom found a pipe where the outflow

entered the river. He looked down at the river, and he saw a

manatee looking up, drawn by the crisp, clear water flowing from

the spring. And that's when Tom started working on a plan to

restore the spring, located within shouting distance of downtown

Tampa.

Photos and info from Old Florida - blog by Rick Kilby

|

|

|

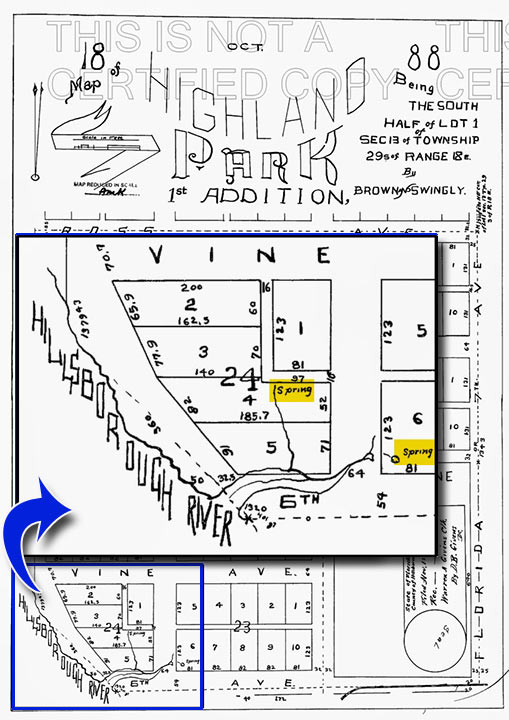

The main source

of the spring seems to be under Highland Ave. according to

this map. A secondary spring can be seen just

northwest of the main spring flow.

|

Tom Ries found another spring on this 1888 plat map of the area

and found that it was located under the water works building and

was being piped into the bay. It's now being piped into the

Ulele run, adding to the flow rate.

In 2010, a project was initiated by the Ecosphere Restoration

Institute to recreate this natural spring run. Money to restore

the spring came from a $50,000 federal grant, $50,000 from the

Southwest Florida Water Management District and $50,000 from the

city. The engineering and design portion of this project was

funded, in part, through the Southeast Aquatic Resources

Partnership’s NOAA Community-based Restoration Program. The water

from the spring pool at that time was piped to the river,

according to city parks spokeswoman Linda Carlo. The restoration

eliminated the pipe and created a basin where water could

pool as it flowed to the river. Approximately 500 feet of

stream was restored and the spring ‘boil’ and associated ecosystem

was also expanded in size and enhanced.

Below is a

before/after view of the spring's cascade from the source pool

leading to the basin.

Place your cursor on it to change it.

In April of

2011 Bob Buckhorn took office as Tampa’s 58th mayor after

winning a runoff election with almost 63 percent of the vote.

Among his goals was to build on the success of the new Tampa

Museum of Art and Curtis Hixon Waterfront Park, bringing more

residents downtown and building cultural attractions in and around

the downtown core.

On September 13, 2011, the newly-elected city council

released a Request for Proposals (RFP) for the acquisition

(long-term lease or lease with option to purchase) and

redevelopment of a portion of the Water Works Building as a café

or restaurant. Columbia Restaurant Group, Ella’s Americana Folk

Art Café, The Straz Center for the Performing Arts, and Water

Works Enterprises all submitted a proposal for review. The

responses

were due Oct. 13, 2011 and can be viewed

online at

www.tampagov.net/pao. A renovation of the building, along with a

planned upgrade of the neighboring Water Works Park, was expected

to energize Tampa Heights.

|

|

|

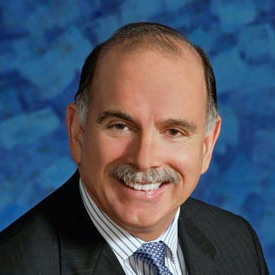

Richard

Gonzmart

President & CEO of

Columbia Restaurant Group |

The bid in

January 2012 eventually went to the Columbia Restaurant Group,

owner of seven Columbia restaurants in Florida, including the

iconic founding location in Ybor City. The group bought a 20-year

lease for $1 a year, with three subsequent renewable 20-year

options.

Richard

Gonzmart, president and CEO, argued passionately for his

company’s proposal, drawing on his family’s ties to Tampa Heights.

Among four other bids, the only other serious contender was from

the owners of Ella’s Americana Folk Art Cafe in Seminole Heights.

More importantly,

the Columbia bid won the support of the mayor, who believed the

waterfront was underutilized and in need of restaurants.

Portions of the

above are from

Ulele, a restaurant for the next century, by Tribune Staff

writer/photographer Jeff Houck, Aug. 10, 2014

Place your cursor on the old photos above and below to restore it

into the beautiful Ulele Restaurant

| On August

24th, 2017, the week of Ulele's 3rd anniversary,

Ulele Restaurant shared this post and these photos on their

Facebook page:

With only a few days until we celebrate our third

anniversary on Saturday, it seems fitting to look back five

years ago to the summer of 2012, when Ulele was more of an

idea in fourth-generation Columbia Restaurant Group

President and CEO Richard Gonzmart's mind than a restaurant

and new riverfront gathering place for Tampa.

In 2012, the

red-brick building of Water Works No. 3 was still being used

by the city of Tampa as a makeshift garage and storage

facility. The roof was dilapidated. Windows were either

malfunctioning or boarded to prevent intruders from living

inside.

A burn mark

scarred the concrete footer inside from where someone had

made a campfire. The Tampa Riverwalk stopped just south of

Kennedy Boulevard with a promise of extending north. Ulele

Spring was choked with weeds and spilled tens of thousands

of gallons of fresh into the Hillsborough River through an

earth-covered pipe instead of the lagoon that stands today.

The Water

Works building had to be gutted to the shell and rebuilt

from the inside out if it was to become Ulele.

Overgrown

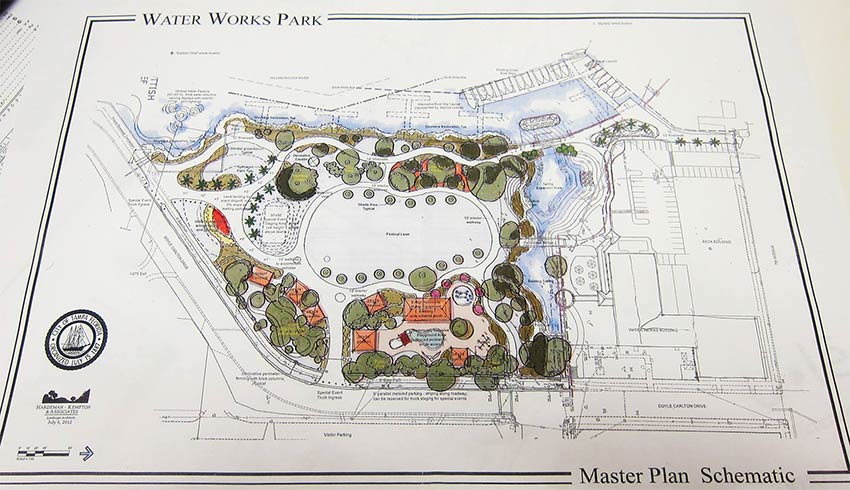

and deserted land next door had yet to be remade into Water

Works Park with a stage, boat docks, dog park and a public

splash park for children.

A 2012 view of the park at the west end of the waterworks building

- Photo by Tom Ries from the Southeast Aquatics website.

Area top of photo where the new spring basin would be constructed.

The City also solicited bids on a project to extend the Riverwalk

at the park north to Seventh Avenue and south to Doyle Carlton

Drive. Work started in the first quarter of 2012.

City officials also worked on plans to add lighting and decorative

fencing and restore Ulele Spring.

Five years

later, the award-winning, native-inspired restaurant and

craft brewery located in Tampa Heights on the northern end

of the Riverwalk is open for lunch, dinner and private

events. In 2014, Ulele earned a prestigious

Golden Spoon

Award from Florida Trend magazine. Earlier in 2017,

OpenTable named it among the Top 100 U.S. Hot Spots for

2017. Ulele's success has become a catalyst for the revival

of the historic Tampa Heights neighborhood where brothers

Richard and Casey Gonzmart were born. |

|

|

A view of the offices of the Beck Group, architects and

construction team of the waterworks building.

Ulele Spring will soon will be a feature in Water Works Park, a

stop along the Tampa Riverwalk.

By Elisabeth Parker, Times Staff Writer, photo by Skip O'Rourke -

Friday, February 21, 2014

Feb. 2014 Tampa's old Water Works Building slowly transforms to

Ulele restaurant - Tampa Bay Times

Construction on the new spring basin, April 2014

Old Florida blog - Ulele Spring 2.0

Construction on the new spring basin, April 2014

Old Florida blog - Ulele Spring 2.0

The Ulele Spring run to the Hillsborough River under restoration

and soon ready for planting native plants later that month or in

early June. Rains earlier in the month delayed the project.

Once-forgotten spring may soon flow again - BY LENORA LAKE Special

Correspondent Published: May 21, 2014

Volunteers helped on May 10, 2014 with the removal of invasive

species of plants and the planting of native ones at Ulele

Springs,

Another planting was to be held in late May or early June.

Once-forgotten spring may soon flow again - BY LENORA LAKE Special

Correspondent Published: May 21, 2014

Plan Hillsborough - River board supports Ulele Springs restoration

On August 12, 2014,

the city celebrated the newly completed Water Works Park in

historic Tampa Heights with a formal ribbon cutting at followed by

a large festival in the park including commemorative fireworks on

Saturday, August 16, 2014.

The 5-acre Water

Works Park includes a play area modeled after a ship, splash pad,

8,500 sq. ft. dog run, performance pavilion, and open lawn for

events. The Tampa Riverwalk was also extended to run throughout

the park along the Hillsborough River. A kayak launch, eight boat

slips and a water taxi stop will be installed once the permits are

approved. Ulele Spring, formerly called Magbee Spring, was

restored and opened to river. In addition to the park improvements

and spring restoration, the City of Tampa leased the historic

Water Works Building adjacent to the park to the Columbia

Restaurant Group. Ulele represents a $5 million renovation of the

former city pumping station.

Oct. 2015

Photo by TampaPix

Today, Ulele's spring shines as the focal piece of the City of Tampa’s

new Water Work’s Park along the Riverwalk and is a natural feature that

is drawing visitors world-wide to the area and enhancing, not only the

habitat for fish and wildlife, but providing positive economic and

recreational opportunities for years to come.

Oct. 2015

Photo by TampaPix

Oct. 2015

Photo by TampaPix

Photo by Tom Ries at SARP website below.

See the Southeast Aquatics Resources Partnership website for a detail

and timeline of the whole project.

The Ulele Spring source, Oct. 2015

Photo by TampaPix

Oct. 2015

Photo by TampaPix

Oct. 2015

Photo by TampaPix

Oct. 2015

Photo by TampaPix

|

|

|

|

Oct. 2015

Photos by TampaPix |

Oct. 2015

Photo by TampaPix

Oct. 2015

Photo by TampaPix

Oct. 2015

Photo by TampaPix

Feb. 11, 2017

Photo by TampaPix

The Beck Group office

building, Feb. 2017

Photo by TampaPix

Looking west towards the spring

basin and the Hillsborough River, Feb. 11, 2017

Photo by TampaPix

Feb. 11, 2017

The pedestrian bridge over the spring run and the event pavilion.

Photo by TampaPix

Click map to view larger

Image from

Old Florida blog - Ulele Spring 2.0

|

Ulele is a native-inspired restaurant and brewery, using fresh

fruits, vegetables, seafood and other proteins from Florida when they

are available, just as my ancestors did. Open since August 2014, Ulele

sits on the banks of the Hillsborough River next to the Ulele Spring. It

is adjacent to the Water Works Park, which has been transformed into a

family-friendly park thanks to our Tampa Mayor and City Council.

Ulele is a native-inspired restaurant and brewery, using fresh

fruits, vegetables, seafood and other proteins from Florida when they

are available, just as my ancestors did. Open since August 2014, Ulele

sits on the banks of the Hillsborough River next to the Ulele Spring. It

is adjacent to the Water Works Park, which has been transformed into a

family-friendly park thanks to our Tampa Mayor and City Council.

Arthur Edwin Boardman,

President of the Macon (Georgia) Gas, Light & Water Co., had been

elected city engineer in Macon in 1872.

Arthur Edwin Boardman,

President of the Macon (Georgia) Gas, Light & Water Co., had been

elected city engineer in Macon in 1872.

Colonel

Brooke referred to another spring a short distance from the

Government Spring, but the name of this one is unknown. This

small spring was said to have been at 10th Avenue and 16th

Street. Its waters were visible until the late 1970s to early

1980s at 4th and 5th Avenues as it trickled toward the Ybor

Estuary. Two magnificent buildings, El Centro Español and La

Logia del Aguila de Oro, later known as the Labor Temple, were

erected over the creek fed by this spring. Don Jose Acosta built

his home over the spring’s source. Through the ensuing years the

sidewalk and the street in front of the house continued to sink,

a condition which forced Acosta to reinforce the foundations to

his home with annoying frequency.

Colonel

Brooke referred to another spring a short distance from the

Government Spring, but the name of this one is unknown. This

small spring was said to have been at 10th Avenue and 16th

Street. Its waters were visible until the late 1970s to early

1980s at 4th and 5th Avenues as it trickled toward the Ybor

Estuary. Two magnificent buildings, El Centro Español and La

Logia del Aguila de Oro, later known as the Labor Temple, were

erected over the creek fed by this spring. Don Jose Acosta built

his home over the spring’s source. Through the ensuing years the

sidewalk and the street in front of the house continued to sink,

a condition which forced Acosta to reinforce the foundations to

his home with annoying frequency.

This

1915 Sanborn map above shows the location of the Tampa Water Works Co. pumping

station in pink on the left with the

spring pool (unlabeled) just below it. Across Highland Ave.

was the old pumping station which was then used in emergencies.

Notice the large 3.5 million gallon, concrete-lined rectangular

reservoir under construction.

This

1915 Sanborn map above shows the location of the Tampa Water Works Co. pumping

station in pink on the left with the

spring pool (unlabeled) just below it. Across Highland Ave.

was the old pumping station which was then used in emergencies.

Notice the large 3.5 million gallon, concrete-lined rectangular

reservoir under construction.

Most

of Tampa's drinking water is treated surface water from the

Hillsborough River. The river begins in the Green Swamp and winds

its way through Tampa to Hillsborough Bay. In Tampa's Sulphur

Springs area, the river reaches the Hillsborough River Dam. The

Hillsborough River Reservoir, the stretch of river between the dam

and the 40th Street Bridge, impounds more than 1 billion gallons

of water. The reservoir holds Tampa's primary drinking water

source, which is treated at the adjacent David L. Tippin Water

Treatment Facility.

Most

of Tampa's drinking water is treated surface water from the

Hillsborough River. The river begins in the Green Swamp and winds

its way through Tampa to Hillsborough Bay. In Tampa's Sulphur

Springs area, the river reaches the Hillsborough River Dam. The

Hillsborough River Reservoir, the stretch of river between the dam

and the 40th Street Bridge, impounds more than 1 billion gallons

of water. The reservoir holds Tampa's primary drinking water

source, which is treated at the adjacent David L. Tippin Water

Treatment Facility.