|

|

The Lafayette

Street Bridge -

Part 2 of 4 |

|

|

|

The Lafayette

Street Bridge -

Part 2 of 4 |

|

|

THE SECOND LAFAYETTE STREET BRIDGE

|

|

|

Bridges are designed to meet the conditions of the time when they are built

and are rarely designed for what future conditions might be. Tampa’s leaders

did not consider things like electricity and streetcars when the first Lafayette

Street Bridge was built, nor the probable extent of suburban development across

the river.

The first Lafayette Street Bridge did not hold up well. In September 1892, city engineer J.H. Neff reported to the mayor that the west approach of the bridge was in a dangerously poor condition, and recommended that all of the pilings should be replaced. Neff regarded the bridge approach’s design to be a “very inferior plan.” That same month the electric company’s cable at the bridge burned out, causing the electric company to use a switch connection to connect wires. Every time the drawbridge opened at night, Hyde Park’s lights went out until the bridge closed.

|

The city council passed an ordinance authorizing the issuance of $350,000 in

bonds to take care of the city’s outstanding debt, and to pay for street paving,

bridge repairs, and other infrastructure needs. However, some citizens felt that

it was imprudent for Tampa to be issuing bonds at this time.

Opponents of the bonds, led by F. A. Salomonson, filed an injunction, whereupon Judge Barron Phillips found that the ordinance had been drawn illegally. The city then appealed the decision to the state supreme court. Although the city incurred an additional expense of $2,000 in legal fees to fight the suit, Salomonson claimed that he had only acted upon his patriotic duty as a citizen. |

|

|

Financing Becomes a Campaign

Issue Salomonson, the former mayor, was once again a mayoral candidate. Therefore, the bridge and the bonds became an issue in the campaign of March 1895, a heated contest between Salomonson and M.B. Macfarlane. Matthew Biggar Macfarlane, a native of Scotland educated in the northern United States, was a lawyer and later served as Collector of Customs for the District of Tampa. M. B. and Hugh Macfarlane were brothers. M.B. Macfarlane was also quite prominent in Florida’s Republican Party, and would be an unsuccessful mayoral candidate in 1895 and unsuccessful gubernatorial candidate in 1900 and 1904. |

|

|

Frederick Salomonson was born in Almelo, Netherlands and in 1882, arrived in New York as a representative of a Dutch syndicate that had purchased vast tracts of land in Florida. After completing his business, Salomonson decided to remain in Florida and moved to Jacksonville where he worked two years for a railroad company. In late 1884, Salomonson relocated to Tampa where he attempted to establish himself in the real estate business and married Florence A. Newcomb on Jan.1, 1885. He realized that railroad access to Tampa and the expansion of its harbor facilities would greatly increase the value of town’s real estate. However, it was not until 1887, when he met John Henry Fessenden, with whom he co-founded the Tampa Real Estate and Loan Association, that Salomonson met with success. Salomonson was the manager of the Tampa Real Estate & Loan Association, and in 1892, he built a home on the bay’s shore at the foot of Hyde Park Avenue and sold the surrounding lots. This area is now condos, offices and the Hyde Park Avenue overpass of Bayshore for access to Davis Islands. By 1895, he had served three terms as city councilman. Salomonson won the mayoral race by a margin of 50 votes in 1893, and the Tribune editorialized: “It is a triumph of the people over the monopolists, over the wreckers, obstructionists, taxeaters, and politicians.” F. A. Salomonson served three terms as Mayor of Tampa, 1893-94, 1895-96, and 1904-1906. Following Henry B. Plant’s death in 1899, the holding company couldn’t get out of the hotel business quickly enough. The showplace, once the jewel of Tampa, had become known as "Plant's Folly" and had been profitless for some time, so it was put up for sale. F. A. Salomonson, made a ridiculous offer of $125,000 and it was snapped up. His first callers turned out to be City tax collectors who presented a large bill for delinquent and current taxes. Salomonson, claiming the property was sold to him free of encumbrances, backed out of the deal. So for $90,000 and the cancellation of tax bills, the City of Tampa in 1906 became the owner of a world-famous hotel. See "Tampa

Bay Hotel is 90 Years Old" by Hampton Dunn, The Sunland

Tribune, Nov. 1981. |

||

|

THE FIRE AT ROTTEN ROW Tibbetts Corner, Lafayette and Franklin St. |

|

|

|

|

|

Franklin St. between Lafayette and Jackson, 1884

Above and to the right are Sanborn fire insurance maps showing almost all the structures on this block were made of wood (yellow buildings.) Stone buildings were colored blue, brick structures pink. The Tibbetts brothers owned a confectionery on this block, and if they were around in 1884, they may have been at Franklin and Lafayette's southeast corner where you see "Bakery Restaurt" in the 1884 map. A "1" or a "2" indicates 1-story or 2-story structure. |

Franklin St. between Lafayette and Jackson, 1887

Place your cursor on the map to see this area in 1889 Notice that by 1889, there were trolley tracks on Franklin St. and Lafayette which did not exist on the 1884 or 1887 maps, and many of the new spaces have not yet been occupied ("Vac."). A red dot on the 1889 map marks the location of the Tibbetts shop, adjacent to the barber shop. |

|

A

fire destroyed this block in August of 1887. By 1889, the block

was rebuilt with all brick buildings.

TAMPA SCORCHED

Tampa Journal August 4, 1887 THE FIRE |

|

|

|

|

|

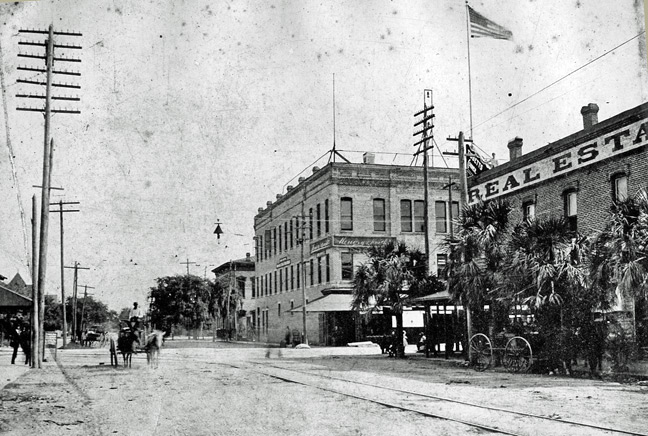

Tibbetts Corner in

1888-89, looking southwest. Notice the barber pole on the street,

left of center of photo.

|

|

A view of Tibbetts Corner in the 1890s, looking east along Lafayette. The progress is apparent: Trolley tracks on Lafayette curve northward and merge with Franklin St. tracks, telephone poles, street lights, flag pole and trees. Detail below shows close up of the man on the roof by the Tibbetts Corner sign.

|

||||||

|

|||||||

|

Cartter, Milo & Hosea Cartter (M. S. Cartter & Co., St. Louis, Mo.) 127,564 Jun. 4, 1872 Howe truss configuration. One-piece shoe to receive the timber end post, timber. Timber top chord and crossed diagonals. Wrought-iron bottom chord and verticals. Special shoe connects bottom chord, end post, vertical rod, and timber diagonal. |

Florida

Dredging Company Selected to Build the Bridge In late February 1895, the city council had authorized a loan of $45,000 to build a new bridge across the Hillsborough River at Lafayette Street. Mayor Easley and the bridge committee had hired the Florida Dredging Company.

The Florida Dredging Company,

based in Jacksonville, specialized in river and harbor improvements. Milo

S. Cartter (also of M.S. Cartter & Co., which supplied the iron work for

the bridge) was President of Florida Dredging Company. In 1894,

Cartter, along with Capt. James A. Bryan, and others, organized The

Florida Dredging Company, with Bryan as General Manager in Tampa.

James E. and Alexander R. Merrill and Arthur Stevens of the

Merrill-Stevens Engineering Company were the directors. Bond Issues Settled Less than two weeks after his re-election as mayor, Salomonson spoke to the city council about the city’s financial state. The outstanding bonded indebtedness of the city was $100,000, and the funded indebtedness was also $100,000, for a total debt of $200,000. Property in Tampa was assessed at approximately $5 million, but the city’s script was selling slowly. Salomonson recanted his prior ardent stand against the sale of bonds, while acknowledging his continuing concern about faults in the city charter and inequities in how the funds would be distributed. He recommended that the city first draw up a new charter, then vote a bonds issue, then install a sewer system and build a new bridge at Lafayette Street. The council agreed, and instructed the city attorney to draw up a new charter authorizing a Board of Public Works and changing mayoral elections from annual to biennial events. |

|

Construction Begins The Florida Dredging Company began building the second Lafayette Street Bridge on June 1, 1895. At the same time, workers built a footway 100 feet upstream from the old bridge as a temporary crossing. Although there were as many as twenty-five men at a time working on the bridge, Tampans urged the contractors to use more workers and finish the bridge more quickly. Meanwhile, construction became a public spectacle, and the builders asked rubberneckers to stay out of their way, because bridge building was a complicated undertaking. Workers cleared old bridge timbers out of the river and the Water Works Water Company re-laid mains on both sides of the river at the bridge. Crews drove pilings for retaining walls, and laid timbers on the pilings. Masons covered the tops of the timbers. Divers built cofferdams around pier emplacements. |

104,110 Jun. 14, 1870 Howe truss configuration. Timber upper chord and diagonals. Lower chord of interlocking iron plates. Single iron shoe to receive both diagonals at panel points. |

|

More Controversy--Mayor Salomonson

Questions Decisions |

|

| On May 23, 1895, the Tampa Morning Tribune announced that the City had awarded Captain John Angus McKay a contract to fill the Lafayette Street Bridge abutments, at a cost of 45 cents per cubic yard. On May 28, the city council met in a special session. One issue brought up by Mayor Salomonson (who had taken office in March 1895 for his second term, after Mayor Robert Easely), was the question of how McKay had been given this abutment contract for 45 cents when a Mr. Black was doing the same type of work for only 20 cents. Secondly, the city had closed the Lafayette Street Bridge without proper public notice (the contract for city printing was awarded to one paper, but the notice appeared in the other). Thirdly, partial demolition had rendered the bridge unusable. Salomonson’s opinion was that the only thing to do was finish the work as quickly as possible. | Bridge issues were only part of a long litany of mayoral complaints about how the city’s business was being handled: the contracts for city improvements were not on file at the city archives, the contracts had not been signed by the mayor (as required), proper public notices had not been filed for work to be done, correct public approval of paving projects as specified by state law had not been obtained, various city departments had not been filing required reports, there were no records of what lots had been sold in the city cemetery, etc. While some of these issues are minor and others more significant, together they paint the picture of a small-town government overwhelmed by growth. |

|

The McKay Family in Tampa John Angus McKay was the third son of Captain James McKay, Sr. and Matilda Cail McKay. James was a native of Scotland who was one of Tampa's early pioneers, arriving here in 1846 with considerable means and rapidly added to his wealth; soon becoming the leading citizen in financial affairs. He engaged here in the mercantile business, advancing supplies and money to the farmers to grow their cotton crops. He also engaged largely in shipping, his vessels increasing fast in number, and making profitable voyages to many southern ports, foreign and domestic. During the Civil War, he was one of the primary blockade runners of Tampa Bay against the Union navy. McKay, who had not relinquished his British citizenship when he came to this country, ran his blockade-running ships under the English flag, until he was captured by the Union Navy and imprisoned at Ft. Taylor in Key West. He served as the 6th Mayor of Tampa and municipal judge in 1859-1860 without holding American citizenship, which may be a real oddity in American politics. He also owned much real estate and cattle in Tampa and surrounding areas. The McKay family home was located at Franklin St. and Jackson St., where today's 1 Tampa City Center skyscraper sits. See The Final Battle for Fort Brooke at Tampapix |

|

|

Capt. James McKay, Sr. |

James

McKay's oldest son, James McKay, Jr., was elected State Senator in

1881. After the arrival of the railroad to Tampa in 1884, McKay, Jr.

became the commander of the H. B. Plant Steamship Line which plied the

Caribbean Sea. During the Spanish-American War, Captain McKay, Jr.

headed the expeditionary fleet which took General Shafter’s Army to Cuba.

He showed great skill and ability in the loading of troops and materials

at Port Tampa, and the unloading on the coast of Cuba. The former rebel

received laudable praises from many in high office in Washington for

bravery and his excellent performance in the war effort. James McKay, Jr.

served as Tampa's 34th mayor from June 5, 1902 to June 5, 1904. James

McKay's oldest son, James McKay, Jr., was elected State Senator in

1881. After the arrival of the railroad to Tampa in 1884, McKay, Jr.

became the commander of the H. B. Plant Steamship Line which plied the

Caribbean Sea. During the Spanish-American War, Captain McKay, Jr.

headed the expeditionary fleet which took General Shafter’s Army to Cuba.

He showed great skill and ability in the loading of troops and materials

at Port Tampa, and the unloading on the coast of Cuba. The former rebel

received laudable praises from many in high office in Washington for

bravery and his excellent performance in the war effort. James McKay, Jr.

served as Tampa's 34th mayor from June 5, 1902 to June 5, 1904.

Capt. John Angus McKay the 3rd son of James McKay, Sr. and Matilda, like his father and brother James, also became a sea captain. He commanded several of his father’s ships, and served the Confederate army throughout the war. After the war he served as deputy collector of customs at the port of Tampa for several years, and in 1870, was elected as a delegate to the State Conservative Convention. In 1876, he was elected to serve as chairman of the County Commission. In the latter part of the 1870s he purchased the Orange Grove Hotel, the most popular hostelry in pioneer days.

|

One of his lasting contributions to Florida is the preservation of Florida history through his "Pioneer Florida" series which appeared in the Sunday Tribune for approximately 15 years. The Tampa Historical Society honors his memory with the yearly D. B. McKay Award for outstanding service in the cause of Florida history.

|

|

Read much more about the entire McKay family

at:

James McKay, I, the Scottish Chief of Tampa Bay by Tony Pizzo and James

McKay, II by Edwin Dart Lambright

Also see

Genealogical Records of

the Pioneers of Tampa and some who came after them and

13th

Judicial Circuit - Courthouse History. Here at TampaPix, see the

McKay family tree. |

|

|

Tampa City Hall, Police Dept. and Tampa's Oldest Existing House |

|

|

|

Tampa City Hall and Tampa Police Dept.

Headquarters at 315 Lafayette, 1905. Florida Avenue is on the

left, Lafayette St. is on the right. At the far left edge can be seen

a small portion of what is now the oldest house in Tampa -- the Stalnaker

house. |

|

Construction Halted Due To Funding

Cut Off In June 1895, the municipal government enacted the new city charter, and almost immediately, the city council approved an ordinance calling for the sale of $350,000 in bonds. Construction work at the Lafayette Street Bridge halted on December 7, 1895, when the city cut off funding pending the results of the bond issue. The election results were a resounding 451 yeas versus 10 nays, showing an electorate strongly in favor of the bonds. At the January 1, 1896, city council meeting, Councilman Wall proposed a resolution that the unfinished bridge across the Hillsborough river be turned over to the commissioners of Public Works with instructions to finish said bridge, and that an appropriation of $15,000 be and the same is hereby made out of the $25,000 raised by bonds for general municipal improvements, and that said commissioners be requested to finish said bridge as soon as possible out of the first money coming in to their hands from the sale of bonds. Councilmen Ramirez and Pons,

of the Fourth Ward, adamantly opposed Wall’s resolution, Ramirez asserting

that it was unfair to set a large amount aside for an improvement that

would only benefit two wards (the first and the third). Pons added that he

felt it unfair to take money from one ward and spend it in another,

skeptically adding that there was no guarantee that the bridge would not

end up costing $100,000. |

|

|

|

Councilmen Holmes, Dorsey, and Wall countered Ramirez and Pons, arguing that the bridge would indeed benefit the entire city; additionally, if the “ward plan” of appropriations were to be followed, no improvements would ever be made anywhere in the city. Regardless of whether finishing the new Lafayette Street Bridge would benefit the rest of the city, Hyde Park residents were certainly anxious for its completion. For them, the temporary footbridge was “an eyesore and a necessary evil.” The footbridge was a jinx for the towboat Mabie, which ran into it not once, but twice in a single week. The optimism felt in City Hall and Hyde Park after the resounding approval of the bonds quickly evaporated. |

| H. B. Plant Declines To Provide Funding Tampa city councilmen had yet to hear anything from W. N. Coler & Company, the New York bankers who had agreed to sell Tampa’s bonds. As of January 30, 1896, the city had received no money and no explanation from Coler & Co. The city council approached Henry B. Plant asking the Plant Investment Company to loan the $15,000 needed to finish the bridge; Plant turned them down. Plant rarely contributed money towards utility construction or public works in cities served by his railroads or where he had hotels, and avoided political or close personal associations in those cities.

|

|

|

Funding Arrives - Construction Resumes In mid February 1896, the city received its first installment from the bonds of $11,000, and the bridge builders resumed work. Unfortunately, Tampa’s struggles with Coler & Co. continued for some time. The Tribune railed against Coler for months, accusing the company of hampering Tampa’s growth: “Instead of muddy streets and gloomy countenances, the people would be buoyant with bright anticipation of great improvements.” In December 1897, Pinnel & Co. of Chicago offered to take the entire issue, but the Board of Public Works rejected the offer because the deal would make it impossible to finish the proposed sewage system before quarantine regulations against excavations were to be enforced the following spring. Finally, in early 1898, the city announced that Rudolph Kleybolte & Co., of Cincinnati, through New York bankers and brokers Pierson & McCutcheson, had purchased the remainder of the bonds.

|

|

|

The Second Lafayette Street Bridge Opens At the end of February 1896, Councilman Brengle of the bridge committee reported that the new bridge should open within a week. Brengle’s estimate proved to be a little optimistic, but on March 21, 1896, the second Lafayette Street Bridge did open to the public. In the middle of a Saturday morning, with little ceremony, workers cast aside the barriers at the feet of the bridge. The first carriage to cross was that of Mr. Hathaway, Manager of the Tampa Bay Hotel, who was accompanied by F. de C. Sullivan, Henry Plant’s private secretary. Together Hathaway and Sullivan drove to Mayor Salomonsen’s office, where City Engineer Neff and councilmen Brengle, Wall, and Beckwith joined them. These men then went to the Tampa Bay Hotel for an elegant lunch. Although few people were present at the bridge’s opening, word quickly spread and that afternoon a solid stream of wagons, carriages, and pedestrians flowed across the river. |

|

|

Formal Dedication Ceremonies A few days later, city leaders formally dedicated the bridge, with many flourishes. The Fifth Battalion Band played as eighteen mounted policemen and three carriages of dignitaries neared the bridge. Crowds of spectators filled the approaches. The hose wagon, engine, and hook and ladder truck from Station One added to the festive atmosphere, as Fire Chief Harris’ daughter Leslie waved to the crowds from amidst a mass of flowers. Precisely at the center of the bridge, the parade halted, as Reverend W. W. DeHart rose in his carriage, uncovered his head, and spoke: “In the name of the commonwealth of Tampa I now declare this bridge open on this the 24th day of March, 1896, and call on you one and all to join in giving three cheers and a tiger.” And so the parade continued to the grounds of the Tampa Bay Hotel where DeHart spoke from a balcony, heralding the bridge as tangible evidence of Tampa’s manifest destiny. |

|

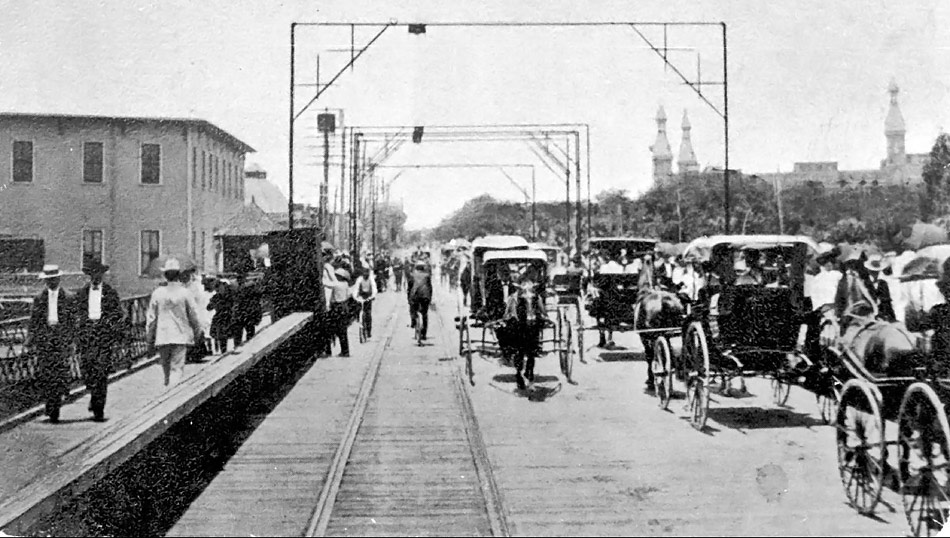

| On March 28, 1896, the first streetcar crossed the bridge. Mrs. Chester W. Chapin,

owner of the Consumers Electric Light and Street Railway Company ("Consumers"), gathered a

party in her custom-made parlor coach, which traveled from Ballast Point, to

Hyde Park, then across the bridge, to Franklin Street and thence to Ybor City. By time the car turned to go back, dusk had fallen and the partygoers shot Roman

candles from the trolley. On board the Chapin coach that day were Mr. and Mrs.

Chapin, their two daughters, F. Ward Chapin, Mayor Salomonson, J.A. Rummell, T.

C. Taliaferro, Peter O. Knight, H.C. Cooper, and G.D. Munsing.

|

|

| Crowds gather

on the 2nd Lafayette Street bridge for a parade, possibly for the grand

opening in 1896. (Source claims date of 1898) Note the temporary footbridge upstream on the right, in the process of being dismantled. |

|

|

The

Evolution of Tampa's Early Street Railway Systems |

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Ballast

Point

|

|

The

park had amusements for adults and children. There was a Ferris wheel

and playground equipment. Animals were enclosed within a fence that

surrounded the banyan tree. The grounds provided ample space for

families to lay tablecloths and spread lavish picnics from baskets. The

park had amusements for adults and children. There was a Ferris wheel

and playground equipment. Animals were enclosed within a fence that

surrounded the banyan tree. The grounds provided ample space for

families to lay tablecloths and spread lavish picnics from baskets.

Jules Verne Park at Ballast Pt. was thus named by Mrs. Chapin, with her streetcar line carrying picnickers to the park for gala outings. Many romances blossomed under the moonlight as dancers partied on the handsome pavilion at the pier. Consumers went broke in 1899 and was sold to the Tampa Electric Co. This event caused the loss of one of the city's most unusual sights: the private trolley car of Mrs. Chapin. She had used the private car to sally forth to do her shopping, visit friends and run other errands; now this privilege was denied her. The Chapins soon moved from Tampa.

In 1897, at a cost of $150,000 an electrical dam was built on the river by Consumers Electric Light and Street Railway Company. The dam was located halfway between present-day 40th Street and 56th Street on the Hillsborough River (today's Temple Crest neighborhood.) On December 13, 1898 the dam was dynamited by cattle barons angry at the loss of grazing land. They tried three times in the years to follow. The first on January 8, 1897, shortly after construction was completed. When the water is low, remnants of the dynamited dam can be seen. In 1899 TECO bought the Consumers Electric Light and Street Railway Company and built a new electric generating dam downstream of the original site, north of Sulphur Springs. This 1899 Sanborn fire insurance map shows the Consumers Electric Light & Street Railway Company's power house upstream on the Hillsborough River, 5 miles northeast of the courthouse.

In 1933, 24 hours of torrential rains

caused the 2nd TECO dam to fail and flood the lower portions of the

river, including Josiah Richardson's already suffering resort at Sulphur

Springs. Richardson had mortgaged the entire resort ($180,000 at

the time) to finance the construction of the water tower. Damage

to the resort was heavy, as well as to his shopping mecca, the Sulphur

Springs Arcade. Already in the midst of the Great Depression, the

businesses in the arcade failed, the Sulphur Springs Bank failed, and

Richardson lost everything.

The fire insurance map detail shows the plant operated night and day, and steam power from the coal and wood boilers generated the electricity only 3 months of the year. The boilers can be seen in pink (brick) with the brick chimney to the left. The rest of the year, the power from the water rushing through the turbines (blue - stone structure) generated power. The turbine shafts were connected by belts running into the building from the top, which turned the shafts connected to the dynamos, the small black squares along the dotted line at the top of the yellow structure. See this image larger.

Photouring Florida, "Jules Verne Park", by Hampton Dunn

Ballast

Point, Cow Pastures to Condominiums by Patty Dervaes

|

|

| The City Benefits by Contract with Consumers Many of the new homes being built were elegant mansions for Tampa’s elite, and the streetcar made it possible for them to escape the city. The streetcar line benefited greatly from the Lafayette Street Bridge, and was of particular interest to the Chapins, who lived in a mansion on the Bayshore. Consumers had a contract with the city allowing the streetcar line to use the bridge, and requiring the company to pay a portion of the cost to repair the approaches. The contract dated March 13, 1896, provided for payment of $100 per year rental. |

|

A view from the Tampa Bay Hotel,

1898

This image is cropped from a larger image, see

full size

|

||||

|

The second Lafayette

Street bridge and Tampa Bay Hotel in 1902

|

A Tampa Electric "Birney" streetcar crossing the

2nd Lafayette St. bridge, 1902

Read about the resurrection of Tampa's Birney streetcars that currently run in

Tampa, and see photos of them at Tampapix's feature

"Tampa Streetcar Fest 2004"

|

The Honeymoon Is Over The bridge had not been long open before public opinion turned from “crowning achievement” to something less favorable. On April 9, 1896, the Weekly Tribune reported that a well-known local architect had said the approaches to the bridge were dangerous -- dangerous for the bridge.

Mr. Knight, a civil engineer with South Florida Railroad, reported to the City Council a month later that the bridge was sound. But evidently the sand was a problem, and in the summer of 1896, the Board of Public Works hired W. H. Kendrick to pave the approaches. This was the first brick pavement laid in Tampa. As a local contractor, one of Kendrick’s best-known construction projects was the Hillsborough County courthouse. A third-generation Tampan, Kendrick was also involved in the city’s early streetcar companies. At the time, most Tampa streets were either unpaved or covered with cypress wood blocks. The blocks were poor pavers, as they rotted and had to be removed after a few years. The Good Road Movement was beginning to take shape nationwide, and many Tampa city council meetings discussed the cost/benefit aspects of paving streets with cypress, crushed rock, clay, or brick. |

|||||

|

|

Repeated Bridge Failures

The second Lafayette Street Bridge

failed repeatedly. At times, it froze in the open position, blocking automotive

and streetcar traffic; other times it refused to open, disrupting river traffic.

Either way, it was a constant nagging source of irritation. One late summer

Sunday morning in 1898, the Lafayette Street Bridge broke when a small metal

piece, a yoke only four inches across, cracked just as the draw opened to let a

steamboat pass. Hyde Park residents were compelled to use rowboats to cross the

river, or to venture into West Tampa to cross the Fortune Street Bridge. Frank

Bruen was notified as soon as the

bridge stopped in the full open position, and set out to find City Engineer Hazelhurst. Mr. Hazelhurst was

ill, but his assistant was available. Perhaps

tongue in check, the Tampa Morning Tribune reported: “Knowing that quick work

was needed he soon drafted the plans for a new steel yoke, and sent the same to

the Merrill-Stevens Engineering Company, of Jacksonville, by mail Sunday night,

with an order to make the same at once.” |

| The next day Bruen pointed out to

the engineers that Shea & Krause of Tampa could make the piece just as easily

and much more quickly. Until the bridge was fixed, which was accomplished by the

end of the week, a naval reserve cutter ran as a ferryboat. Unfortunately, the

repair lasted only until October, when the same small piece of metal again gave

way.

Mayor Bowyer came to the rescue, rushing to the Tampa Fish and Ice Company

and requisitioning two boats for a free ferry service. This time, it took Shea &

Krause about five days and $500 to fix the bridge. Shea & Krause

were fated to have many struggles with the recalcitrant bridge. What had once

been a front-page story became merely a mention deep into the paper, as bridge

failures became commonplace. Metal bridges require frequent

maintenance, for example, painting, to stay in good operational condition. One

advantage to the concrete bridges that became popular in the twentieth century

was a reduction in maintenance costs. Frank C. Bowyer, a native of West Virginia, came to Tampa in 1890. He worked as a broker and was the Tampa Steamship Company’s South Florida manager. Bowyer served as mayor from June 1898 to June 1900, including the Spanish-American War. Like so many of Tampa’s mayors, Bowyer was challenged by the growing city’s insufficient public works and municipal budgets too small to correct the shortcomings. Bowyer later served on the Chamber of Commerce and the Tampa Board of Trade. In 1900, Hillsborough County commissioners awarded a contract to the Virginia Bridge Iron Company to build a span across the Alafia River between Peru and Riverview, and the new drawbridge used the old Lafayette ironwork. |

|

|

Hyde Park and Bayshore Residents Want a New Bridge When the second bridge proved inadequate and unreliable, Hyde Park and Bayshore residents and real estate agents claimed that construction of a new bridge would benefit the whole city. Yet it took years to get the new bridge. Tampa’s government was strongly conservative when it came to fiscal matters, as were the voters, and bond issue after bond issue for public improvements was rejected or never even came to vote. |

|

|

Tampa

During the Spanish-American War, 1898

The Generals planned the war campaigns from the hotel. Officers and war correspondents stayed here in relative luxury, rocking on the veranda, sipping iced tea and planning and reporting strategies. Colonel Teddy Roosevelt and the Rough Riders trained in the camps near the hotel during the day. Clara Barton gathered supplies for the Red Cross and frequented the hotel. The enlisted men camped in tents around Tampa and other Florida cities, fought off mosquitoes, endured stifling temperatures, wool uniforms and boredom while waiting for the signal to start the war.

Encampment at Port Tampa

Col. Teddy Roosevelt, 1898

Cuban volunteers performing target practice in West Tampa

Troops at Port Tampa getting ready to board their ships

Troops charging through the water at Port Tampa

You can see hundreds of photos taken in Tampa during the Spanish American War at the Harvard Collection. Do a "Quick Search" for Tampa at the upper right of this page. Some hits will be photos not taken in Tampa, but part of a collection that includes "Tampa" in the title.

See more

about the Spanish American War here at TampaPix's feature about the

Burgert Brothers |

|||||||||||||

|

TEDDY ROOSEVELT "SPEAR FISHING IN 1898" There are photos all over the web claiming to be Col. Roosevelt spear fishing "devil rays" in 1898 while in Tampa before or after battle in Cuba during the Spanish-American war. THESE ARE NOT FROM 1898, THEY ARE FROM 1917, EIGHT YEARS AFTER HE WAS PRESIDENT.

June 17, 1918 - Theodore Roosevelt stands with Russell J. Coles. Both are dressed in commencement ceremony regalia, having received honorary degrees from Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut. The picture's verso states that this is Roosevelt's personal copy of the photograph, and that it was presented by his son, Archibald Roosevelt, to Murray H. Coggeshall, a graduate of Trinity, in 1947 This is what Col. Roosevelt looked like in 1898.

Punta Gorda History Center Blog |

|||||||||||||

|

Thomas Edison Film shot in Tampa, March

1898 From Edison films "war extra" catalog: A wide plain, dotted with tents, gleaming white in the bright sunshine. Soldiers moving about everywhere, at all sorts of duties. In the background looms up a big cigar factory; giving the prosaic touch to the picture needful to bring out in sharp contrast the patriotism with which the scene inspires us. The camera was on a rapidly moving train, so the panoramic view is a wide one, and remarkably brilliant.

The Library of Congress, American Memory Collection - Motion Pictures |

|||||||||||||

|

Robert Mugge - A Tampa Success Story This section about Robert Mugge has moved to a separate page, here.

|

First Lafayette St. Bridge Second Lafayette St. Bridge Third Lafayette St. Bridge The Bridge Today - Kennedy Blvd.

Sources

"Tampa's Lafayette Street bridge: Building a New South City" by Lucy D. Jones, University of South Florida

Leo Stalnaker: Fearless Fundamentalist, For Whom Life was “High Adventure", by Morrison Buck

Robert Mugge, Pioneer Tampan by Margaret Regener. Hurner, granddaughter of Robert Mugge

"Abstracts and Chronology of American Truss Bridge Patents, 1817-1900" by David Guise

Duval County GenWeb Biography of Capt. James A. Bryan

Streetcars in Tampa and St. Petersburg by Robert Lehman

In Search of David Paul Davis, by Rodney Kite-Powell

A Guide to Historic Tampa, by Steve Rajtar

Tampa, the Early Years, by Robert Kaiser

U.S. Patent and Trademark Office

Historic photos courtesy of

USF Special Collections Digital Archives

University of

Florida Digital Collections, George Smathers Library

Florida Memory Project Photograph Collection, State Archives

Burgert Brothers Collection, HCPLC

Library of Congress Digital Collections