|

RMS Majestic

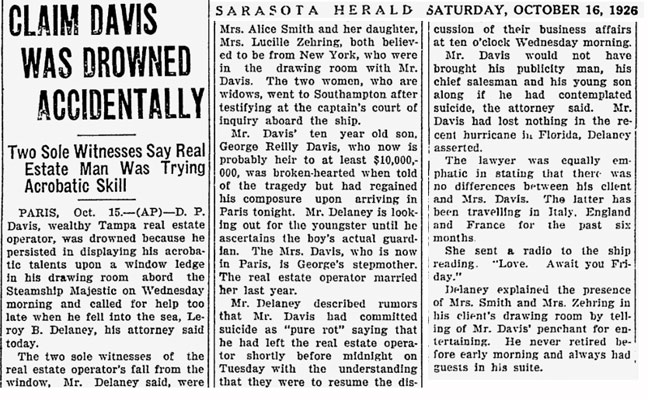

"Lowry's findings regarding Davis' death did not assuage all doubts on the subject. Many felt that Davis leapt overboard to end his life. Chief among this theory's proponents was the captain of the Majestic. Another who thought Davis killed himself was Jerome McLeod, who had joined D. P. Davis Properties in 1925 as assistant publicity director after a stint at the Tampa Daily Times. "He got drunk," McLeod told a later interviewer, and when he got drunk he got maudlin. A third story comes from a steward who stood outside Davis' room and overheard an argument between Davis and Zehring. The Majestic's employee claimed Davis said, "I can go on living or end it. I can make money or spend it. It all depends on you." The statement was punctuated by a loud splash. This runs somewhat counter to the testimony given Lowry, in which the steward had to be told of Davis' fall by Zehring. Davis' brother Milton had a different story. While acknowledging D. P. Davis had a drinking problem, he believed his death was an accident. Milton traveled to New York City to speak with Zehring about his brother's final moments. Milton, who claimed David probably intended to divorce his second wife and marry his girlfriend, restated Zehring's recollection: "Lucille said there had been a party and D. P. was sitting in an open porthole, one of those big ones. It was storming outside, and he blew out the window. She said she started to scream and grab his leg, but it was blown out of her hands. That's what happened." "There are a variety of problems and inconsistencies with each of these stories. Some say that Davis and Zehring were alone while others say there was a party. The Majestic was among the largest ocean liners in the world and undoubtedly had large portholes, and Davis was a small man, but could he really sit in one and then be blown overboard? Could the steward standing outside of the closed stateroom door hear a loud splash that occurred outside the ship and dozens of yards below the open window? The idea that Davis booked passage with a large party, including Davis Properties employees, places doubt that the intent of the voyage was to divorce his wife." "Murder, too, is a possibility. Some stories relate that Davis had up to $50,000 in cash with him. Others discount this, claiming that he hardly ever carried large amounts of money on him. Motive and opportunity do not seem to be on the side of murder, but no one could lead his life without making enemies, especially after losing so much money in such a brief period of time. Yet another theory intimates that Davis faked his death. While discredited by Lowry's investigation and Milton's assurances to the contrary, it remains a possibility. How, or even if, he fell overboard is still a mystery. Until new evidence is found, any theory regarding Davis' death is just that, theory." |

|

Who was Lucille Zehring

and what happened to her after her trip with Davis on the Majestic? |

||||||||

TampaPix was recently

contacted by Jackie Anderson Morris who said her grandfather once spoke of a

half-sister he had and lost contact with after she, her sister and their

parents moved to Los Angeles from England in the early 1900s.

"Grandpa" Edgar Morse Smith had heard in his later years that one of his

half-sisters, Lucille, was involved with a man who fell out of a

porthole of a ship and was never found, and that she or her sister,

Winifred, was a movie star who later married a Duke. TampaPix was recently

contacted by Jackie Anderson Morris who said her grandfather once spoke of a

half-sister he had and lost contact with after she, her sister and their

parents moved to Los Angeles from England in the early 1900s.

"Grandpa" Edgar Morse Smith had heard in his later years that one of his

half-sisters, Lucille, was involved with a man who fell out of a

porthole of a ship and was never found, and that she or her sister,

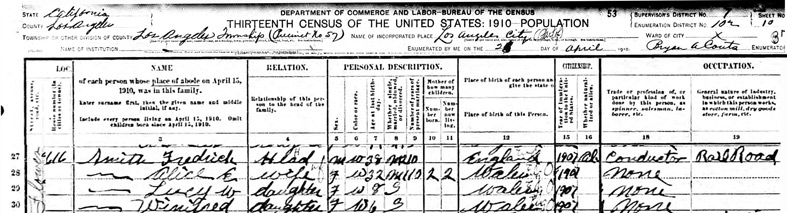

Winifred, was a movie star who later married a Duke. Edgar Morse Smith was born around 1890 in Cardiff, Wales, to Englishman Frederick Morse Smith and Lucy Evans. Edgar's mother Lucy died in childbirth, and Frederick then married around 1900 to Cardiff, Wales native Alice Winters in England. Together, Frederick and Alice had two daughters in Wales, Lucille W. Smith on July 5, 1902 and Winifred V. Smith around 1904. Frederick was born in Hereford, England on Feb. 15, 1872 and settled in Canada around 1905 with his wife and young daughters. He worked as a railway conductor where they lived in Toronto, when they came to the U.S. on Oct. 31, 1907 from Windsor to Port Huron, Michigan on the Grand Trunk Railway and then settled in Los Angeles, California. After settling in L.A., Frederick sent for his son, Edgar, who was living with relatives in England. Edgar learned that his father's relationship with Alice and daughters had become less than ideal and had left him. The reason is probably due to the events that follow. Lucille W. Smith would become the well-known former Mack Sennett bathing beauty, Lucille Zehring, who was the last person to see D. P. Davis alive before he disappeared through the porthole of his cabin on his fateful trip to the French Riviera on the White Star Line ship "Majestic." About the "Morse" middle names of Frederick and Edgar: Samuel Morse, inventor of the telegraph and Morse Code, was an uncle of Frederick Morse. Lucille's background On the 1910 U.S. Census in Los Angeles, Frederick Smith (age 38) and Alice Smith (age 32) were living at 616 S. Flower Street; a home which Frederick rented. Frederick is listed as being from England, with Alice and their daughters from Wales. Their daughters Lucille W. and Winifred were 8 and 6 years old. The record shows that this was Frederick's 2nd marriage and Alice's first marriage; they had been married 10 years. Frederick worked as a conductor for the railroad, and Alice was the mother of 2 children. All family members show they immigrated to the U.S. in 1907.

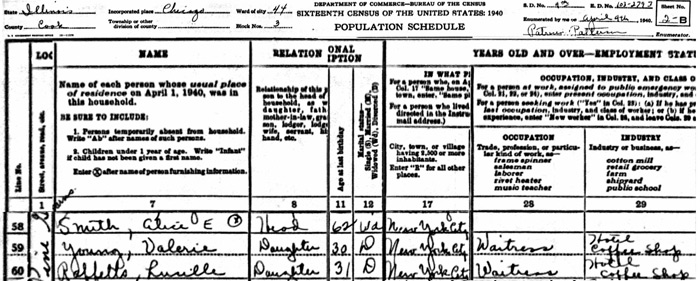

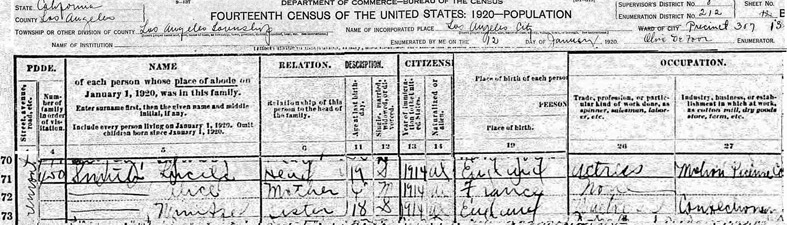

The 1920 census of Los Angeles shows 19-year old Lucille as the head of house, single, with her mother Alice and sister Winifred living with her, but Frederick was not listed in the home, which was located on South Fremont Avenue. Alice indicated she was married. It is likely that the three women moved out of Frederick's home to this location. Lucille worked as actress in the motion picture business, Winifred worked as a waitress at a confectionery. Here, Alice is listed as being from France, with her native tongue being French. This is inaccurate; Frederick's declarations for naturalization mention Alice as being from Cardiff, Wales.

On Oct. 2, 1920, Lucille married Ohio native Llewellyn F. Zehring and in Feb. 1925, they divorced. An Oct. 30, 1927 article in the Baltimore Sun newspaper mentions Lucille as "...Lucille Zehring, following her marriage and divorce from Llewellyn F. Zehring...", as do other news articles and a later marriage record of Lucille's.

Llewellyn F. Zehring Llewellyn Frederick Zehring was born Jan. 16, 1890 in Hamilton, Ohio to Ohio natives Fred Averill Zehring and Laura Llewellyn Zehring. Lew was on the 1900 and 1910 censuses of Dayton, living with his parents, but not on the 1920 census of Dayton. Lew's ages on the 1900 and 1910 records result in an 1889 to 1890 birth year.

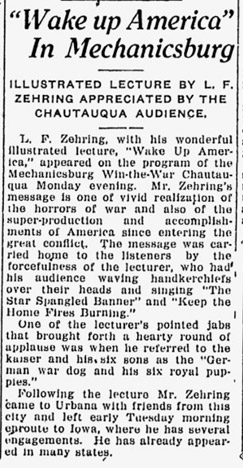

On Llewellyn F. Zehring's 1917 World War I draft registration, he gave his full name, birth date, birth place, occupation (salesman for Steinway & Sons) and marital status--married. He claimed exemption from the draft due to having a dependant wife. Llewellyn's salesmanship and lecturing ability were talents that Lew used during WW1 to stir up Americans in support of the war effort against Germany. This is evident in the article below, "Wake Up America."

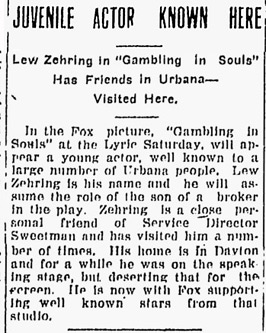

Llewellyn's first name was the surname of his mother's family, Llewellyn, according to Deena Beckman, whose husband is a descendant of Llewellyn Zehring's cousin Laura. Cousin Laura's father was William Zehring, a brother of Lew's mother Laura Llewellyn Zehring. Deena's mother-in-law has said that Llewellyn Zehring had been in a few silent movies and also had a talent for singing opera. Lew's silent movie experience may be how he met Lucille. Gambling in Souls (1919)

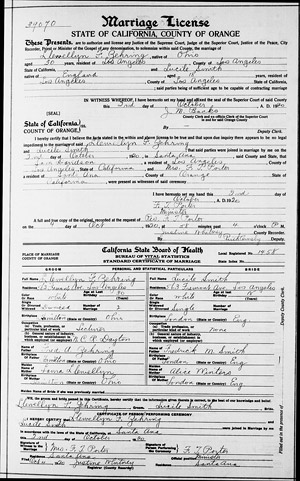

According to county marriages of California, 1850 to 1952, Llewellyn F. Zehring, son of Fred A. Zehring and Laura Llewellyn, married Lucile Smith, daughter of Frederick M. Smith and Alice Winters, on October 2, 1920, in Santa Ana, Orange County, California. On their marriage license, they each gave their address as 563 Freemont. Llewellyn indicated that this was his 2nd marriage, and that he was divorced at the time. He referenced his first marriage on his WW1 draft registration of 1917 when he claimed exemption for having a dependant wife. Lew and Lucille divorced in Feb. of 1925. Click the image at left, then use your browser zoom tool to see larger.

On the 1930 census of Dayton, Lew is once

again living with his parents, and his parents' ward, 26-year old Ruth

Orr. Lew's marital status in 1930 shows he was divorced, which

would be a reference to his marriage with Lucille, yet no

record of him with Lucille has been found. Later in life, Lew

married Ruth Orr but not have any children. Lew died in August of

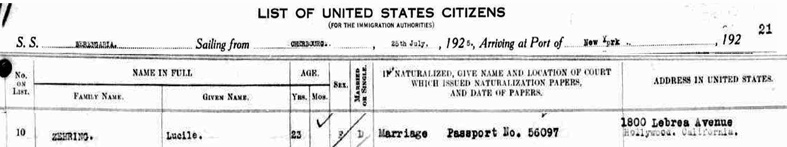

1963 at age 82 and is buried in Dayton Memorial Park Cemetery. Lucille Zehring In late July of 1925, 23-year-old Lucille Zehring arrived in the Port of New York on the SS Berengaria which departed Cherbourg, France on July 25th, 1925. The reason for her visit to France is not known at this time. On the ship's passenger list, in the column named "If naturalized, give name and location of the court which issued naturalization papers, and date", it shows "marriage, Passport No. 56097" a possible indication that she received American citizenship by way of marriage to an American citizen--Llewellyn Zehring. The image below has been edited to conserve horizontal space; a column was removed where the passenger's birth date was to be recorded if they were a native of the United States. The column was blank for Lucille. The passenger list also shows that Lucille was divorced and lived at 1800 Labrea Avenue in Hollywood, California.

There are numerous sources on the Internet that identify the known Mack Sennett "Bathing Beauties" and none list Lucille Zehring or Lucille Smith. Some sites are sources trying to substantiate the claim in the D.P. Davis disappearance stories that Lucille was a Mack Sennett bathing beauty, but have been unsuccessful in finding direct evidence. Lucille's career as one of the bathing beauties may have been short and if she appeared in any movies, may have been unaccredited, but it is apparent in the numerous news articles of the time period that the press accepted the claim.

Photo Identification of Bathing Beauties

Lucille Zehring on the RMS Majestic Not mentioned in the numerous articles about the fateful voyage of D. P. Davis was the fact that Lucille's mother, Alice Smith, was part of Davis' entourage.

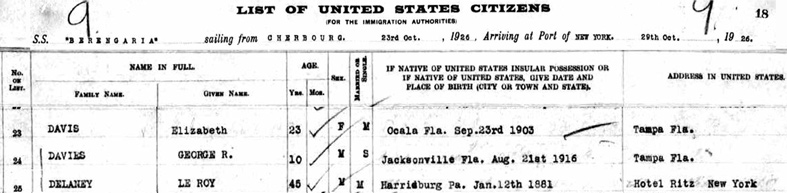

Alice Smith was Lucille's mother, Raymond C. Schindler was a private detective. Also on board was Davis' attorney, Leroy Delaney and Davis' ten-year-old son, George Davis. Numerous theories have been proposed as to why Davis set sail with these people. Some say Davis intended to divorce his wife Elizabeth Nelson for a 2nd time, who was reported to be in Paris; that Schindler came along to investigate her doings there and Delaney came along to handle the divorce. In a 2005 St. Pete Times article, George Davis who was then 83, said he had been asleep and recalled being roused and told that the ship's captain had been unable to find his father. When the ship finally docked in France, George said his father's mistress, a B-movie star, took him sightseeing around Paris. The pair's destinations included the Moulin Rouge. George Davis' return voyage from France The ship's passenger record below shows 10-year-old George R. Davis returning from France on the S.S. Berengaria from Cherbuorg, France on Oct. 29th, 1926. Accompanying him was his step-mother (D. P. Davis' wife), 23-year-old Elizabeth (Nelson) Davis, and Leroy Delaney, Davis' lawyer.

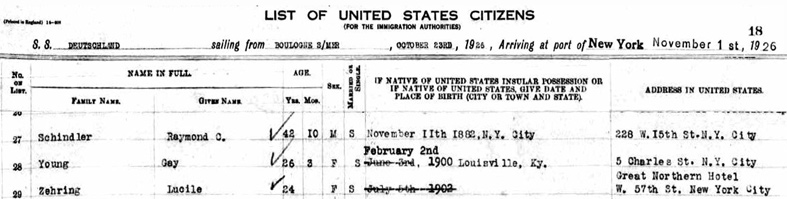

Lucille Zehring and Alice E. Smith's return voyage from France Three days later, Lucille Zehring arrived back in New York, along with Raymond Schindler and Gay Young, on the S.S. Deutschland from Boulogne Sur Mer, France.

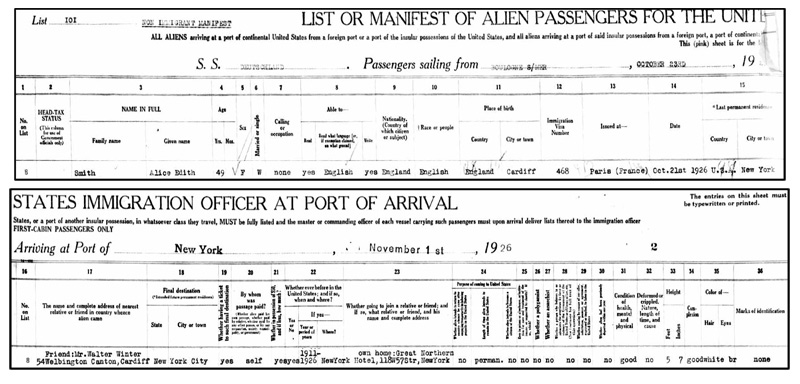

Lucille's mother,

Alice Edith Smith, returned on the same ship on the same passage, but

was listed on a 2-page spread on elsewhere on the manifest.

April 10, 1927

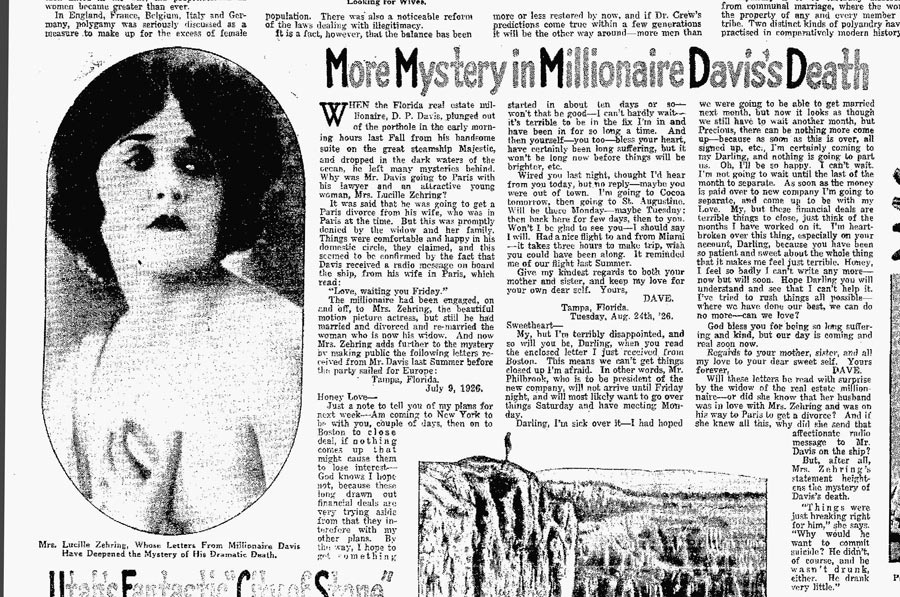

Milwaukee Sentinel In July, 1927, Lucille made public the letters that Davis had written her in the summer of 1926, adding more mystery to already mysterious story. Click the image below, then use your browser's zoom to view larger. Lucille's second marriage--Duke Fabio Carafa D'Andria

At left, "A Titled Romance" - Duke and Duchess Fabio Carafa d'Andria are snapped in the garden of their roof bungalow at New York City following their wedding at New York's municipal building chapel. The Duke is a wealthy coal mine operator of Rome, Italy and the Duchess was formerly Miss Lucille Zehring.

On Aug. 29, 1929, this

article appeared in the Joplin Globe: The next day, on Aug. 30, 1927, the New York Times ran this story, (Valerie is Lucille's sister, Winifred Valerie Smith, who married Howard Young around 1928.) DENIES SEPARATION OF DUKE AHD BRIDE -- Valerie Yale Explains Sailing of Sister, Duchess d'Andria, Wed a Month Ago. NO FAREWELL AT THE PIER - Duke Arrived Half Hour Late, but Report He Wirelessed Wife Not to Use Title Abroad Is Denied.

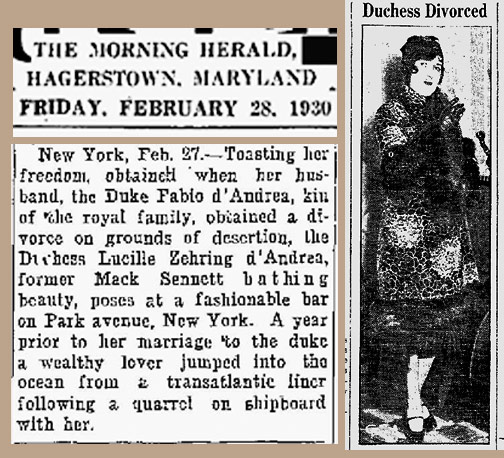

By Feb. 28, 1930, the marriage was over. But Lucille continued to make waves by still calling herself the "Duchess Carafa D'Andria", even as late as 1936.

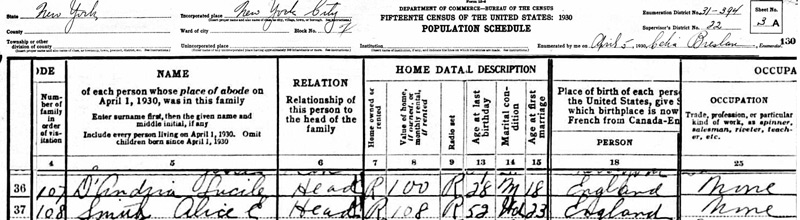

Lucille Smith Zehring Carafa D'Andria after her 2nd divorce The 1930 Census of New York City shows 28-year-old Lucille D'Andria was married and living in apartment 107 at 41-47 W. 72nd Street. Her 52-year-old mother Alice E. Smith lived in apartment 108. Their rent was $100 and $108 a month, respectively, but both showed their occupation as "none." The record shows Alice was widowed, but this may not be so.

According to Dade County, Florida marriage records, Lucille Carafa D'Andria married Joseph L. Raffetto in 1935. Nothing is known about Joseph at this time and it appears that the marriage was not publicized or known of by the press. The story below appeared in the San Antonio Light in Nov. 1936.

The article says, the current Duchess (Renee Thornton) "had a temperamental predecessor, Lucille D'Avril Smith Zehring...Lucille apparently didn't understand that divorce not only cut away her husband but the title marriage had loaned her." It is not known why "D'Avril" was used as part of Lucille's name. It may have been something she concocted from the middle name of her former husband's (Lewellyn Zehring's) father, Fred Averill Zehring. According to her 1910 census, her middle initial was "W."

Hageman's third and present wife considered it a privilege to support her husband. By 1940, Lucille's marriage to Joseph L. Raffetto had ended and she was living in Chicago with her mother, Alice E. Smith, and sister, Winifred Valerie Young. Winifred's marriage to Howard Young also ended in divorce; they had two children Ralph and Douglas Young. Both sisters worked as waitresses in a hotel coffee shop.

Alice died on Nov. 24, 1940 in Chicago. She was buried Nov. 26, 1940 in Wunders Cemetery in Chicago. She was 62. No death record has yet been found for Lucille Raffetto. It is possible she married again and thus had a different surname at the time of her death.

|

"Stories of

Davis'

death always include some element of mystery. The only undisputed facts

are that he went overboard and drowned while en route to Europe aboard the

ocean liner Majestic on October 12, 1926 and that Lucille Zehring

accompanied him on the voyage. What is in question is how he ended up in

the water; by accidentally falling out of a state room window, being

pushed out or jumping out to end his own life."

"Stories of

Davis'

death always include some element of mystery. The only undisputed facts

are that he went overboard and drowned while en route to Europe aboard the

ocean liner Majestic on October 12, 1926 and that Lucille Zehring

accompanied him on the voyage. What is in question is how he ended up in

the water; by accidentally falling out of a state room window, being

pushed out or jumping out to end his own life."

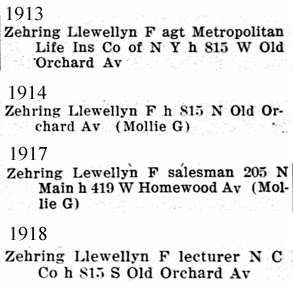

In

1913, Llewellyn Zehring married "Mollie G". Llewellyn is on the

Dayton City directory of 1913 with no spouse listed. Then in 1914,

Mollie is listed as his wife. They are both listed in 1915, 1916 and

1917. Then in 1918 Mollie is no longer listed and Lew's occupation has

become "Lecturer" for NCR Co. They probably divorced in late 1917.

In

1913, Llewellyn Zehring married "Mollie G". Llewellyn is on the

Dayton City directory of 1913 with no spouse listed. Then in 1914,

Mollie is listed as his wife. They are both listed in 1915, 1916 and

1917. Then in 1918 Mollie is no longer listed and Lew's occupation has

become "Lecturer" for NCR Co. They probably divorced in late 1917.

The

very next month, in late August of 1927, Lucille would be in the news

again. This time, for her Aug. 25, 1927 marriage in New York City

to Italian Duke Fabio Carafa D'Andria.

The

very next month, in late August of 1927, Lucille would be in the news

again. This time, for her Aug. 25, 1927 marriage in New York City

to Italian Duke Fabio Carafa D'Andria. Miss

Valerie Vale of 120 West Fifty-eighth Street, sister of the Duchess

d'Andria, denied yesterday published reports that her sister and the

Duke Fabio Carafa d'Andria, a former Fascist officer, who were married

only a month ago, were separated and that she had sailed to Europe

without telling him her intentions.

Miss

Valerie Vale of 120 West Fifty-eighth Street, sister of the Duchess

d'Andria, denied yesterday published reports that her sister and the

Duke Fabio Carafa d'Andria, a former Fascist officer, who were married

only a month ago, were separated and that she had sailed to Europe

without telling him her intentions.

The

story tells about composer Richard Hageman and his three marriages to

opera singers. His first wife, whom he paid $75 a week for her

singing talent, once chased him with a gun. That marriage ended in

divorce in 1916. His 2nd marriage, to Renee Thornton, also ended

in divorce. Renee Thornton Hageman then married the Duke Fabio

Carafa D'Andria in 1936. It is in this context that Lucille, a

former wife of the Duke, is mentioned due to the problem of there now

being two women calling themselves "Duchess Carafa D'Andria."

The

story tells about composer Richard Hageman and his three marriages to

opera singers. His first wife, whom he paid $75 a week for her

singing talent, once chased him with a gun. That marriage ended in

divorce in 1916. His 2nd marriage, to Renee Thornton, also ended

in divorce. Renee Thornton Hageman then married the Duke Fabio

Carafa D'Andria in 1936. It is in this context that Lucille, a

former wife of the Duke, is mentioned due to the problem of there now

being two women calling themselves "Duchess Carafa D'Andria."