This site is not affiliated with the restaurant or the Columbia Restaurant Group and its personnel.

This site is not affiliated

with the restaurant or the Columbia Restaurant Group and its personnel.

Most of the

historic information and historic photos in this feature are from

"The

Columbia Restaurant, Celebrating a Century of History, Culture and Cuisine"

by Andrew Huse.

A "Must-have" book for any Tampa native, it features

history, photos, and recipes.)

|

|

|

|

Casimiro may have become

a full-time restaurateur, but that is not to say he abandoned the sale of

strong drink altogether. It was by no means uncommon, especially in Ybor

City,

|

|

|

|

|

|||

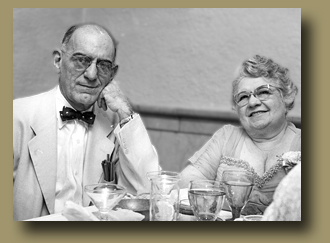

Casimiro Hernandez, Jr. and his wife, Carmen |

|

IT TOOK AN ACT OF CONGRESS TO KEEP THE FINEST SPANISH FOOD IN THE WORLD AT THE COLUMBIA RESTAURANT

Casimiro Hernandez, Jr. held that Chef Pijuan had no peer. As far as Casimiro was concerned, Pijuan was the only master chef at the Columbia. The Columbia's most illustrious chef died in 1949, an irreplaceable master in the kitchen. His last request was to be buried with a Columbia Restaurant menu on his chest; Casimiro himself, placed the menu in Pijuan's arms at the funeral, to be sure he held it just right.

Vincenzo "Sarapico" Perez then became the "de facto" head chef at the Columbia. Starting off as a waiter in the restaurant in 1938, Perez soon worked his way into the kitchen as a chef and advanced in skills under Pijuan. Perez earned his nickname, which meant "Little Bird," because of the way he fluttered about the kitchen in haste, "ruffling his feathers" like a frantic bird. In 1949, the Columbia held a press conference to announce Sarapico as the Columbia's 2nd great chef. The photo at right shows this conference, with Casimiro's son-in-law Cesar Gonzmart making the announcement. Gonzmart, holding up 2 fingers to indicate Perez as the Columbia's 2nd great chef, is standing next to Perez. In the background, Casimiro holds up 1 finger to indicate there would only ever be one great chef at the Columbia--Pijuan. (Story and photos from "The Columbia Restaurant, Celebrating a Century of History, Culture and Cuisine" by Andrew Huse. A "Must-have" book for any Tampa native, it features history, photos, and recipes.)

See newspaper article re:

Act of Congress (Photo in article is not chef Pijuan) |

|

Casimiro Jr. and

his wife, Carmen had one child, Adela Hernandez. Adela was a

beautiful concert pianist who was trained at the Juilliard School of

Music. In 1946, Adela married César Gonzmart, a concert

violinist and handsome showman. They traveled throughout the United States while

César

performed in famous supper clubs during the early 1950’s.

In 1953, Adela’s father, Casimiro Jr., was in failing health, so they returned to Tampa. They divided the business duties of operating the restaurant and raising their two sons, Casey and Richard. The family persevered in keeping the restaurant open during the late 1950s and all thorough the 1960s when Ybor City was dying. Urban renewal cut the heart from the Latin Quarter. More families moved out. Businesses closed. César Gonzmart realized they had to do something to bring people back to Ybor City. |

Adela Gonzmart in the Patio, 1947. Casimiro Jr. built the Patio Dining Room in 1937 to resemble an Andalusia courtyard from the south of Spain. Surrounded by a balcony with a colorful circa 1906 Columbia Restaurant Café mosaic-tiled fountain. The statue "Love (Cupid) and the Dolphin" stands in the middle. It is a replica of a sculpture found in the ruins of Pompeii. A retractable glass skylight was installed, giving the room a wonderful bright and sunny look during the day, and an enchanted glow at night. |

|

Adela Gonzmart performing in a TV studio at WFLA |

|

|

Ernesto Lecuona, composer of "Siboney" (Click photo to listen, song has a 15 second musical intro)

The song is said to be the pleading of a lovesick man for his lover, Siboney. He sings that he dies for her love, and that she is a treasure. At the end, he pleads that the thick of the jungle doesn't drown out the crystal clear echo of his song, as he waits for her in his hut.

In 1934, Lecuona was medically

advised to return to Cuba after suffering from severe pneumonia

while touring in Spain with the band. The band was renamed the

Lecuona Cuban Boys, and under the musical leadership of Oréfiche and

Ernesto "Jaruco" Vázquez, they continued to tour Europe extensively

with considerable success until the outbreak of World War II.

Collections of recordings they made in Europe during this period

have been issued. During the war the band toured Latin America. In

1946, Armando Oréfiche and his tenor saxophone and bongo playing

brother, Adalberto "Chiquito" Oréfiche, left after a leadership

dispute and formed the Havana Cuban Boys. Lecuona chose not to work at the piano while composing, preferring a card table. Typically, he would work in creative bursts that would produce astonishing results. He reportedly once wrote four songs that would become hits: Blue Night, Siboney, Say Si Si, and Dame tus dos rosas/Two Hearts That Pass in the Night, in a single night: January 6, 1929. The following year Andalucia and Malagueña were on the charts. Ernesto's niece, Margarita Lecuona, was a mezzo soprano and accomplished composer. She wrote "Babalu" in 1941, the song made famous to Americans by Desi Arnaz in 1946.

Lecuona composed the scores for four MGM films during the

early '30s, and earned an Academy Award nomination for the title

song to 1942's Always in My Heart. Lecuona, named the

cultural attaché to the Cuban embassy in Washington, D.C., in 1943,

rarely performed after World War II, preferring instead to cultivate

his Cuban farm. He left his native country for Tampa in 1960,

denouncing Castro's revolution and vowing never to play again until

Cuba was free of communism. Apparently, he never did perform

professionally again. He lived his final years in the US. He

died 3 years later while on vacation at Santa Cruz de Tenerife,

Canary Islands, at age 68, and is interred at Gate of Heaven

Cemetery in Hawthorne, New York.

Read a detailed biography about Ernesto Lecuona At Left: Miguel Vicente Bonifacio Roig (then editor of Club and Radiales magazines), Ernesto Lecuona, Cuban troubadour Miguel Matamoro of 'El Trio Matamoros'and Gonzalo Roig. Ernesto Lecuona's music has been used in numerous movies: 1. Charlie Wilson's War (2007) Song ("Siboney") 2. The Lost City, (2006) Song ("La Comparsa"), Song ("Danza Lucumi"), Song ("A La Antigua") 3. Once Upon a Time In Mexico (2003) Song ("Malaguena") 4. Before Night Falls (2001) as Composer 5. Buena Vista Social Club (1999) Documentary, Song ("Canto Siboney") 6. Forces of Nature (1999) Song ("Siboney") 7. The Impostors (1998) Song ("Siboney") 8. Brighton Beach Memoirs (1986) Song ("Jungle Drums (Canto Karabali)") 9. American Pop (1981) Song ("Say Si Si") 10. Ricochet Romance (1954) as Composer 11. As Young As You Feel (1951) as Composer 12. The Daughter of Rosie O'Grady (1950) as Composer 13. When My Baby Smiles at Me (1948) as Composer 14. Carnival in Costa Rica (1947) as Composer 15. Cuban Pete (1946) as Composer 16. Song of Mexico (1945) as Composer, Music Score 17. Song of Mexico (1945) as Composer, Music Score 18. Babes on Swing Street (1944) as Composer 19. Get Going (1943) as Composer 20. It Comes Up Love (1943) as Composer 21. Get Hep to Love (1942) as Composer 22. Always in My Heart (1942) as Composer 23. Swing It Soldier (1941) as Composer 24. When You're in Love (1937) as Composer (credited as Ernest Lecuona) 25. Las fronteras del amor (1934) as Composer 26. La cruz y la espada (1934) as Composer.

|

|

Even while at the helm of Columbia, Gonzmart never quit being the entertainer. Until illness got in the way, he performed regularly at the Ybor City location where music has always been key to the dining experience. César Gonzmart, concert violinist, Spanish "nobleman" and energetic chairman of the Columbia Restaurant group, died after fighting a year-long battle with pancreatic cancer. Waging a gallant and sometimes hopeful fight to the end, the 72-year-old restaurateur passed away at his home in Tampa on Dec 9, 1993.

|

|

The Kings Room - Entrance to the Sancho Dining Room and Patio Dining Room and stairway to the Kings Dining Room |

|

A suit of armor stands guard outside the Sancho Dining Room. |

Photo

from "The

Columbia Restaurant, Celebrating a Century of History, Culture and Cuisine"

by Andrew Huse.