We are

indebted to Captain William H. Davis, commander of the William Bisbee

on her last trip from Rockland, Maine to Tampa, Captain G.A. Hanson,

commander of Ye Mystic Krewe of Gasparilla of Tampa, the records of

the U.S. Customs office and logbooks of the vessel for information

regarding this vessel.

|

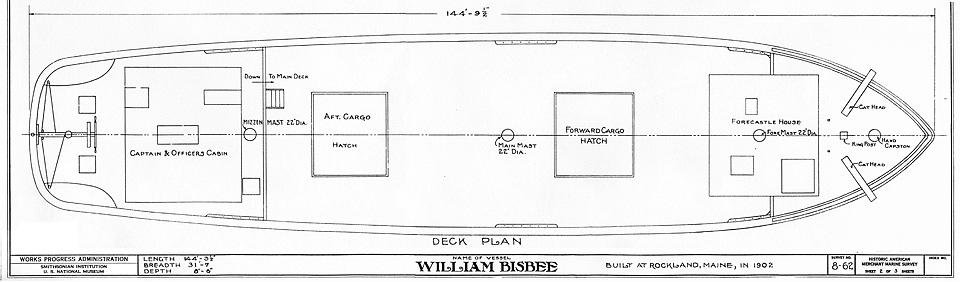

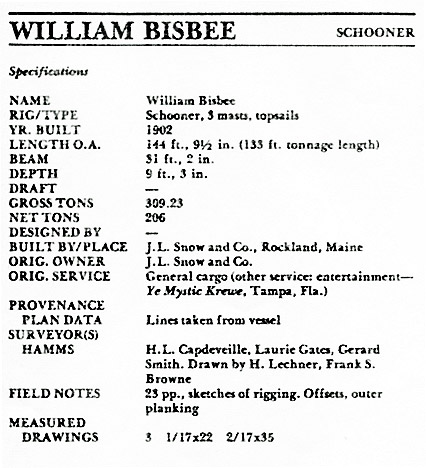

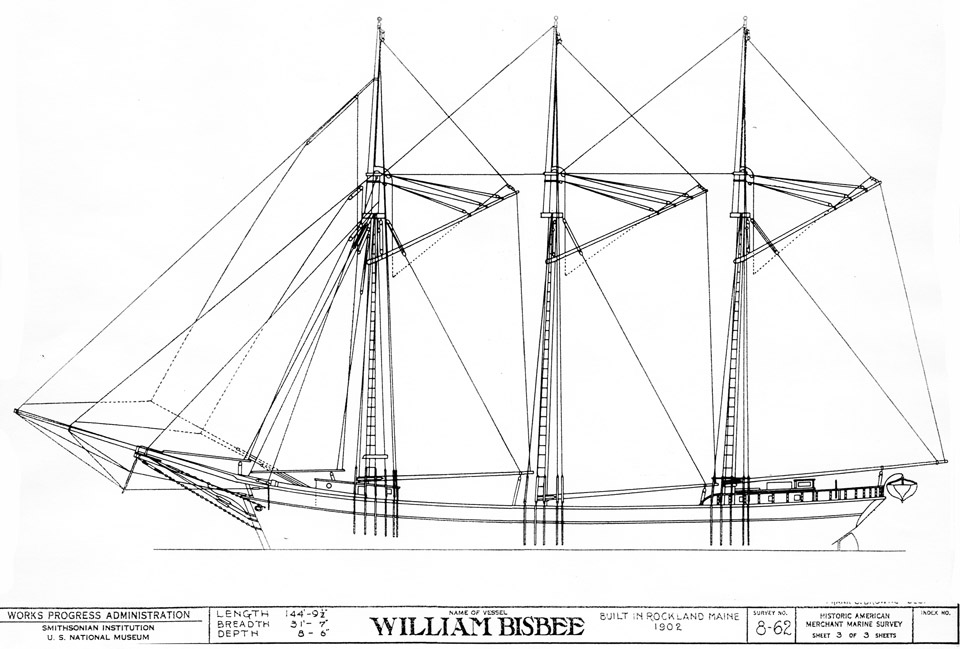

The William

Bisbee was built at Rockland, Maine by J.L. Snow and Co., in 1902.

She was designed for the coastwise trade and operated successfully in

and out of the Atlantic coast ports from Nova Scotia to Central

America, also Gulf of Mexico ports. She competed successfully

with power-driven vessels showing exceptionally fast time between

ports of call.

She was named for U.S. Army

Brigadier General

William Henry Bisbee (1840 - 1942).

|

|

| |

|

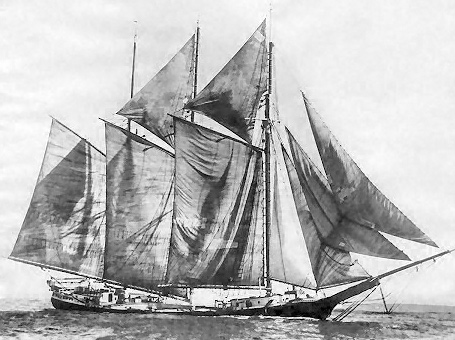

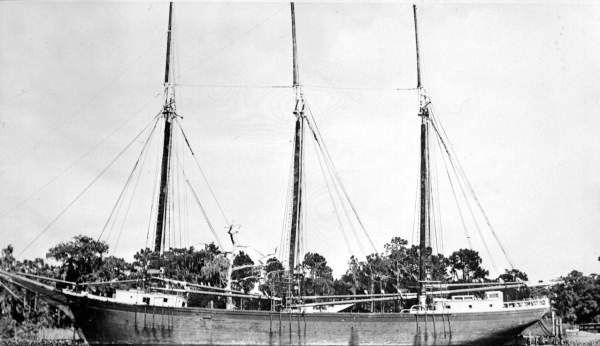

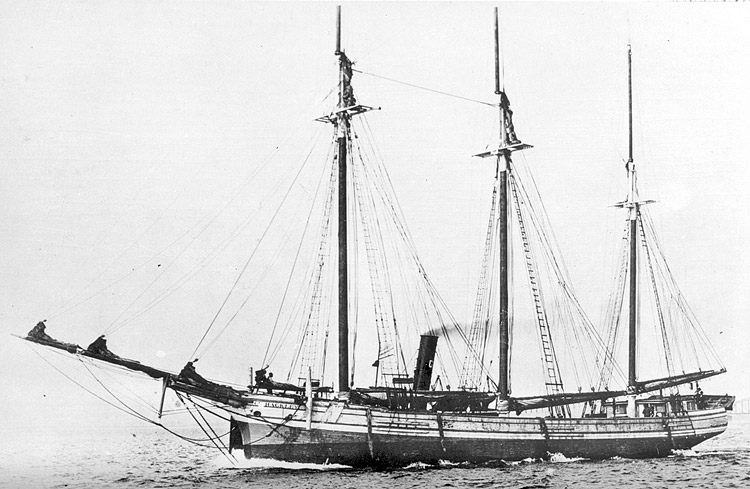

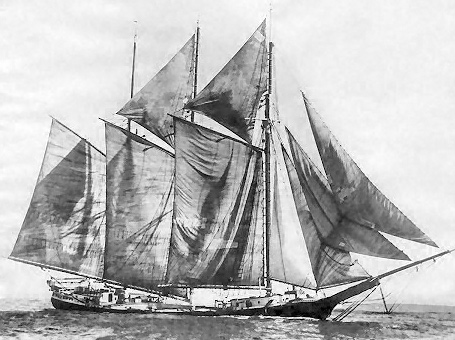

The William

Bisbee fully laden with a cargo of lumber, sitting low in the water

somewhere off the coast of Maine. |

|

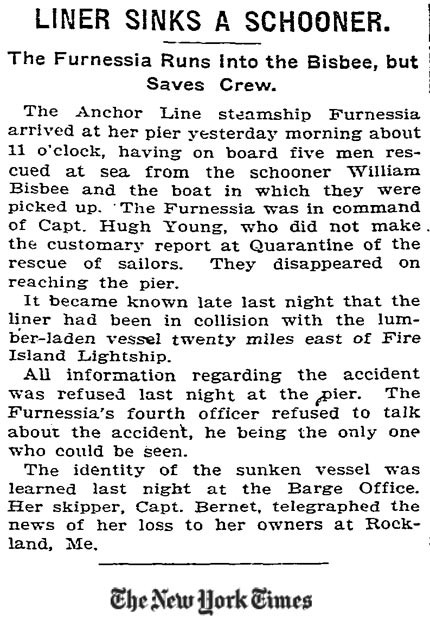

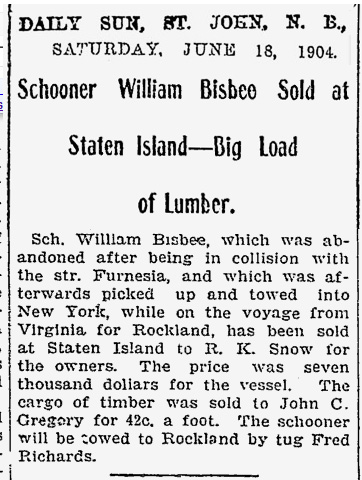

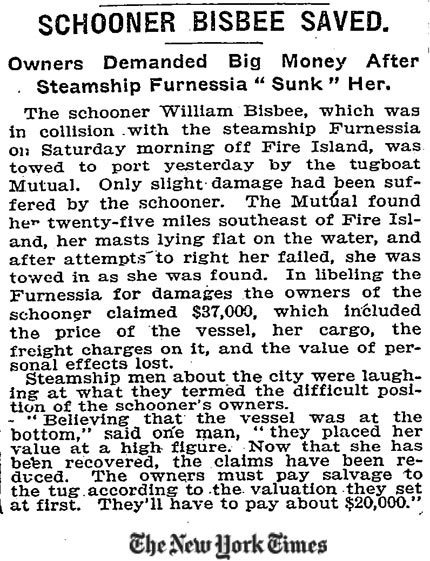

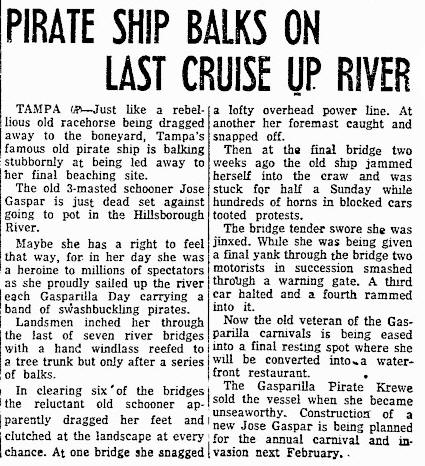

Published May 16, 1904

In

1904, while in route from Virginia to

Rockland, Maine, the Bisbee was sold

to R.K. Snow for $7,000.

|

The SS Furnessia

after her 1891 refitting and renovations.

Previously she had two funnels.

Published May 20, 1904

|

| |

|

District Court, S. D. New York. May 4, 1905

Collision—Steamship And Schooner Crossing—Excessive Speed And Want

for Efficient Lookouts In Fog. A steamship approaching New York at

night in a fog came into collision with a crossing schooner 15 miles

east of Fire Island Lightship. Both vessels were sounding fog

signals. The steamship was admittedly going at a speed of six knots,

and had a lookout on the forecastle head, and another in the crow's

nest on the foremast, but neither saw nor heard the schooner until

she was seen from the bridge, when quite near. At this time a white

light was seen on the schooner nearly ahead, which was mistaken for

a stern light, and the steamship changed her course, but had been

little affected thereby at the time of collision. Held, that the

steamship was In fault for excessive speed and want of efficient

lookouts; that the schooner would not be adjudged in fault because

the mate, in the extremity of the collision, set out a false and

misleading light, it being doubtful whether or not it contributed in

any way to the collision, which was fully accounted for by the plain

faults of the steamship.

|

In Admiralty. Suit for collision. MacFarland, Taylor & Costello, for libellants. _ Robinson, Biddle &

Ward and W. S. Montgomery, for claimant.

ADAMS, District Judge

This action was brought by

John Bernet and Richard K. Snow, the part owners and agents of the

schooner William

Bisbee, to recover the damages arising from a collision between

the schooner and the steamship Furnessia

about 1:45 o'clock A. M. of the 15th day of May, 1904, some 15 miles

east of Fire Island Lightship in the Atlantic Ocean.

The Bisbee, loaded

with oak timber and a small amount of general cargo, was bound from

Gallick's Landing, Virginia, to Rockland, Maine. The steamship, with

passengers and general cargo, was bound from Glasgow to New York. The

weather before and at the time of collision was foggy, dense according

to the steamship's contention, but light according to the schooner's.

The schooner was on

the starboard tack and carrying full sail, fore sail, main sail and

spanker, with 3 top sails, 4 stay sails and 3 jibs. She was not making

very much progress, however, probably 3 knots at the utmost, as there

was a very light wind from the eastward. The mate was steering and a

lookout was stationed on the forecastle head. The latter was using a

mechanical fog horn, of a proper size and type. She also had her lights

duly set and burning.

The steamship ran into a haze shortly after

midnight which thickened into a fog about 20 minutes before the

collision. Her compass course was West by North, 2 degrees North,

which allowing for deviation, gave the steamship practically a West

course. She was at first proceeding at her full speed of 14 or 15 knots

but reduced her speed twice, so that, it is claimed, she was going at

the rate of 6 knots at the time of collision. She had a lookout

stationed on the forecastle head and another in the crow's nest on the

foremast. The fog whistle was duly blown. According to the testimony of

the navigating officers, the first knowledge they had of the vicinity of

the schooner was seeing a white light,

less than a point on the steamship's port bow, in close proximity, which

they took to be a ship's stern light. The wheel was put hard-a-port to

clear the vessel which was supposed to exhibit the light, and when the

steamship was beginning to feel the influence of the helm, a green light

was seen on the port bow, whereupon the steamship was reversed at full

speed, but it was too late to check her headway materially and she

struck the schooner a hard blow a little

abaft amidships on her starboard side, which turned her over.

| |

|

| |

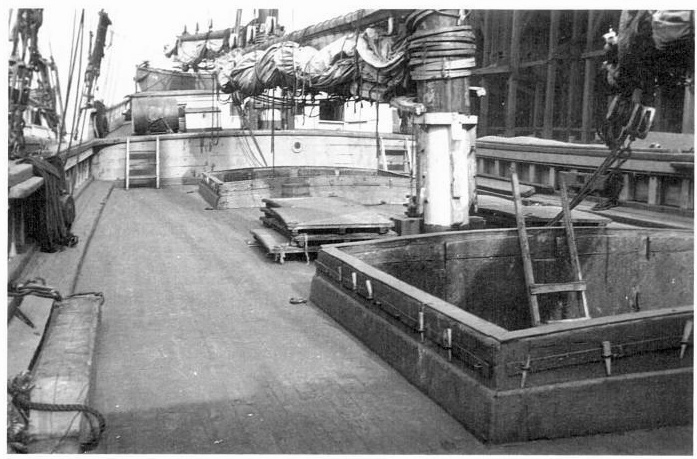

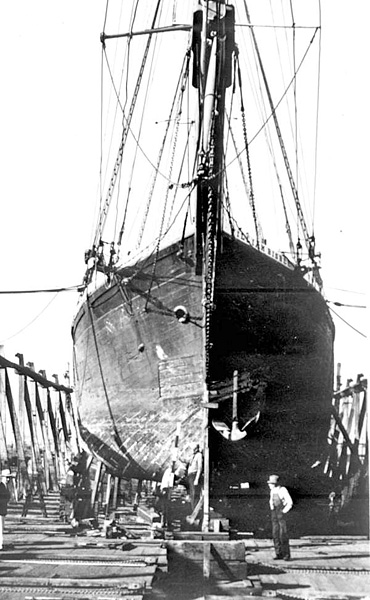

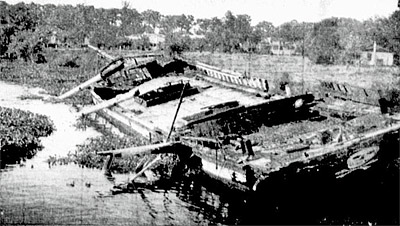

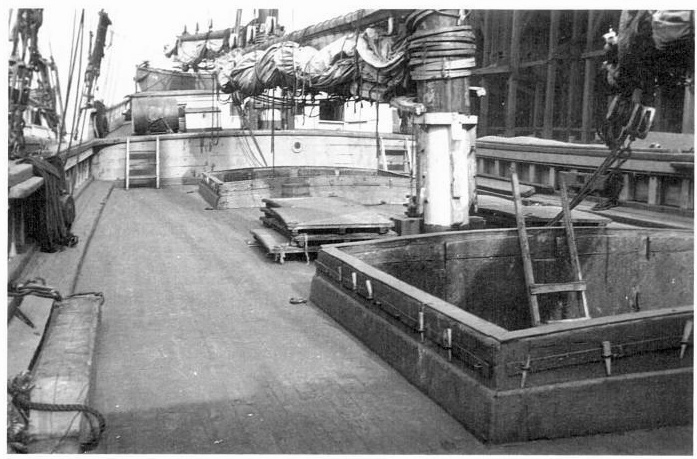

Deck view looking aft aboard the three-masted

schooner William Bisbee.

The broad, wide decks, massive bulwark stanchions, and raised quarterdeck

surrounding an after deckhouse are typical of American vessels. |

The members of the schooner's crew were obliged

to take to the boat which hung at her davits astern. They thus

reached the steamship and were taken aboard and brought to New York.

The schooner's contention is that the steamship

was solely at fault for the collision, principally in that she did

not have sufficient lookouts and was proceeding too fast in a fog.

The steamship's contention is that the

collision was solely produced by the

schooner exhibiting a false light which misled the steamship

into changing her course, bringing about the collision.

The steamship did not take the testimony of her

lookouts but they were hunted up by the

schooner and examined on her behalf. Their testimony does not

seem to be of much importance, as there are circumstances which tend

to discredit the witnesses and I do not consider it necessary to

resort to their statements in disposing of the case, as taking the

steamship's own testimony, she should , be condemned for proceeding

at an undue speed in a dense fog and in not having sufficient

lookouts. If her speed was only 6 knots, it was too much in such a

fog, and the fact that she claims the first knowledge she had of the

presence of the schooner was by

observation from the bridge, suffices to condemn her navigation jn

such respect. The schooner had a

mechanical fog horn which she was using some time before the

collision, but it was not heard on the steamship until the collision

was imminent.

The difficult question in the case is

concerning the exhibition of an irregular light by the

schooner. When the steamship's

presence became known to those on the

schooner, the mate, who was then in charge and steering her,

took the light out of the binnacle, and set it on top of the house,

where it remained until nearly the time of the collision, when it

was put back into the binnacle. The mate explains this by stating

that he was afraid of steamers and always used this precaution. It

was very bad practice on his part and if it had any effect in

producing the collision, the vessel should be condemned for it. The

steamship claims that she supposed that the light was one of an

overtaken vessel shown in conformity with Art. 10 of the sailing

rules.

The steamship's change of course to starboard

tends to show that she was misled by the white light, but she was

then apparently herself in fault, in that

she had, by reason of her excessive speed of 6 knots as admitted,

and it was probably more, and want of efficient lookouts, approached

too close to the schooner. The change

of course on the steamship's part was slight, said by her wheelsman

to have been less than a point and by her officers between 1 and 2

points. The wheelsman was probably correct. If it had been made in

the other direction, the steamship would have gone astern of the

schooner and the collision been

avoided. Without any change, the collision would probably have taken

place by the steamship striking further aft on the

schooner, but it is not profitable to

speculate about what might have taken place, if something else had

been done. What was done, was a steamship striking a sailing vessel

in a fog, proximately through her own excessive speed and want of

efficient lookouts. The schooner

exhibited a false 'and misleading light in the extremity of the

collision. The effect of such exhibition is too doubtful to make the

schooner bear any part of the loss

therefore. The collision is too well accounted for by the

steamship's plain faults to allow a division of the damages. Decree

for the libellants, with an order of reference.

|

| |

|

Mutiny on the Bisbee

In March, 1915,

according to her log, the Bisbee was made ready for sea at

Rockland, Maine, when the crew requested shore leave and were refused.

They mutinied and refused to work. The sails were hoisted by the

captain, mate and cook, who manned the ship. The wind blew a gale in

the night as the vessel was rounding Cape Cod. It was necessary to

shorten sail quickly but proved impossible for three men to do so.

The mate prevailed upon the crew to assist, which they did to save their

lives, thus averting a serious disaster.

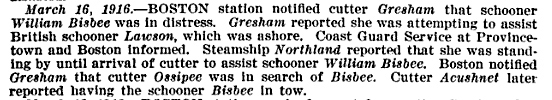

Mother Nature vs. the Bisbee

On March 2, 3, and 4,

1927, while on a voyage from New York to West Point, Virginia, she

encountered a northeast gale. Sail was shortened. Spanker and

all sails were reefed. She ran before the wind. At 10:30pm the

port anchor was dropped about 20 miles southeast of Hog Island. All

of her anchor chain was dropped about 20 miles southeast of Hog Island.

All of her anchor chain (about 75 fathoms) was run out. A tremendous

sea was running throughout the night. At 1:00am the anchor chain

parted and she drifted helplessly in the gale. Her distress signals

were seen by the steamers Halifax, Allegheny and Philadelphia.

The Allegheny wirelessed the revenue cutter Manning to take

the vessel in tow. The Philadelphia tried to tow the vessel

but parted two tow lines. While trying to get a line aboard, the

steamer collided with the jib boom, carrying it away together with the

bowsprit and all head gear and put the windlass out of commission.

The Philadelphia then stood by until the Manning hove

alongside about 11:00pm. Early in the morning of March 4, the

Manning succeeded in getting a line on board and took the vessel in

tow proceeding to Cape Henry where she was anchored at Lynhaven Roads

where repairs were made. The steward, while assisting the sailors in

handling the lines, fell overboard and drowned.

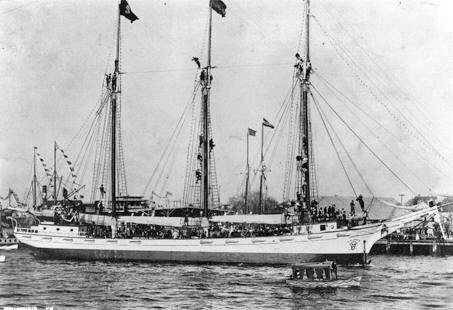

The

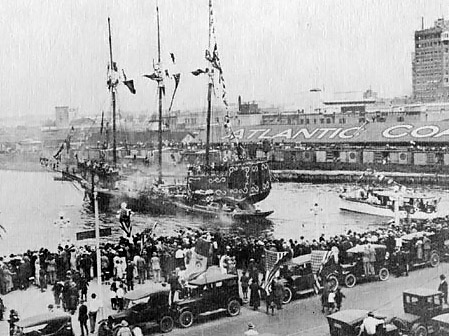

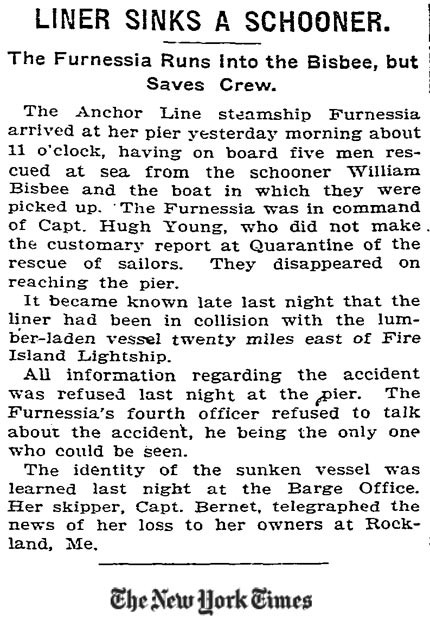

William Bisbee Becomes the José Gaspar

The Bisbee

continued to operate in the coastwide trade until 1932 when she was sold

to Captain Charles Taylor of Eastport who operated her in the offshore

trade until 1936 when she was sold to Victor B. Bendix, a ship and freight

broker who bought her in the interest of Tampa's Gasparilla Festival.

The Bisbee hoisted sail and headed south toward Tampa, smashing into

another ship off Ambrose Light near New York harbor. She reported in

at the Tampa Customs House on Nov. 21, 1936. Bendix resold her "as

is" for $3,150 to Captain G.A. Hanson of Tampa who was commander of Ye

Mystic Krewe. She was soon transformed into the pirate ship,

José Gaspar. This began a new chapter in the history of the

William Bisbee.

|