LOWRY PARK BEGINNINGS

In order to tell the story of Lowry Park's

beginnings it's necessary to go back to the early 1900s of Tampa's

history. It was during the first mayoral term of Donald Brenham McKay

where we must begin the story, because the events that led to the creation of Lowry Park occurred

during his first mayoral term.

McKay became

City Editor of the Tampa Times in 1893, and seven years later, he owned

it and served as its publisher for the next four decades, which

included his terms as Tampa mayor. While he remained de facto

publisher of the Tampa Times, as mayor, D.B. McKay never used his position

to unfairly benefit his newspaper with regards to reporting the news.

In 1927, Tampa voters approved a new City Charter that reinstated the

mayor-city council form of government. Afterward, McKay decided to

campaign for mayor again and was overwhelmingly elected to another

four-year term.

Previous Mayors of Tampa, City of Tampa website

On October 7, 1900, D.B. McKay married

Aurora Gutierrez, a daughter of Gavino Gutierrez. Gavino was a

Spaniard who came to Tampa in search of a place to grow guavas on a large

scale. Before returning to New York, Gutierrez visited Key West and

met up for the first time with Vicente Martinez-Ybor. Both being

engaged in the cigar-making business, it was Gutierrez who persuaded Ybor

to consider visiting Tampa to investigate its superior advantages as a

desirable location for their cigar factories. This was the start of

what would become Ybor City and it's tremendous boost to the Tampa

economy.

From

Tampa Historical Society, About D. B. McKay

SUMTER de LEON LOWRY (SR.)

The Sumter Lowry in this section refers to the senior Lowry, not to

be confused with his son of the same name (Jr.) who was a member of

the National Guard and donated the first elephant to the Lowry Park

zoo.Sumter de Leon Lowry was born in

York, S. Carolina in 1861, a son of Dr. James M. and Louisa (Avery ) Lowry. The

Lowry family was established in South Carolina before the Revolutionary War; Dr. James Lowry was a surgeon in the 17th Carolina Regiment in the

Civil War.

DR. LOWRY SETTLES IN PALATKA,

FLA.

Sumter Lowry attended

South Carolina public schools and King’s Mountain Military School, and studied

pharmacy at the South Carolina Medical College. He first started in business as

a druggist in South Carolina and later owned a drugstore in Palatka, Fla., where

he moved in 1888.

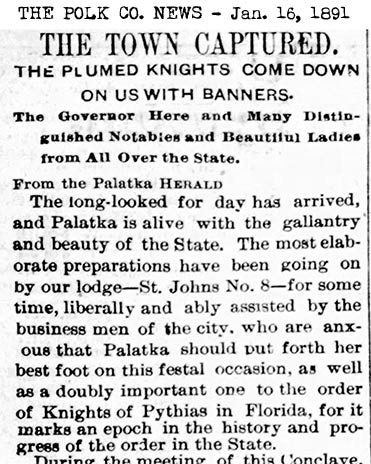

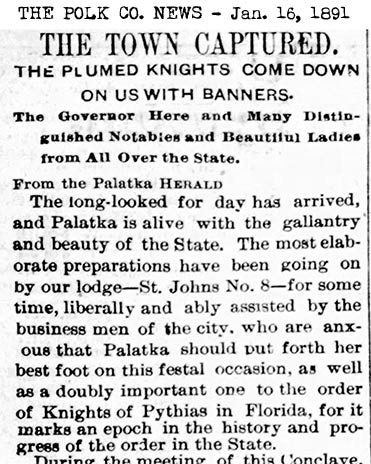

By 1891, Dr. Lowry had entered the

insurance business and was an esteemed member of the Knights of

Pythias lodge.

|

|

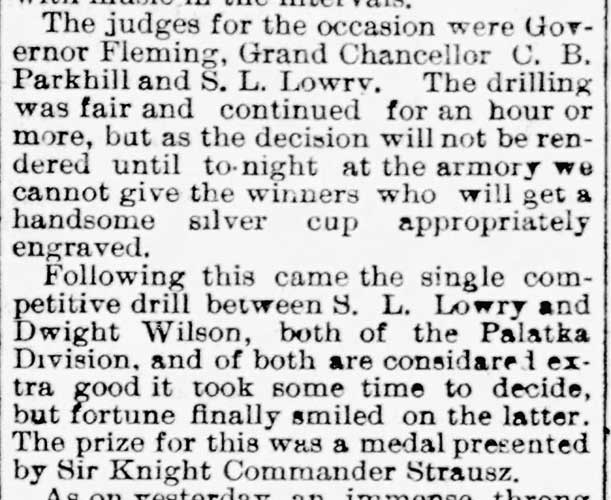

The Knights of

Pythias Lodge, St. Johns No. 8, held their festive celebration

"alive with gallantry and beauty" in January, 1891. The

celebration consisted of an invasion and capturing of

the city, along with parades, marching bands and contests.

(In 1904, Gasparilla would start a yearly tradition very much

in the style of the Pythians.)

Sumter

L. Lowry participated in the events, one of which was a

one-on-one competitive drill with Dwight Wilson. Both

competitors were equal to the task, but "fortune finally

smiled" in favor of Wilson, who received a medal. Sumter

L. Lowry participated in the events, one of which was a

one-on-one competitive drill with Dwight Wilson. Both

competitors were equal to the task, but "fortune finally

smiled" in favor of Wilson, who received a medal.

These are two excerpts

from a large article about the celebration.

|

| |

Mar. 20, 1891:

Dr. Lowry treats a man suffering with blood poisoning. |

|

Lowry apparently

enjoyed fishing as seen by these two articles above and below.

|

|

|

|

Lowry was an

insurance agent before he moved to Tampa. |

|

DR. LOWRY IN TAMPA

Coming to Tampa in

1893, Lowry established the

insurance agency which was still in existence at the time this biographical

sketch was written by Karl Grismer (1950). Lowry also became a director of

the Gulf Life Insurance Company.

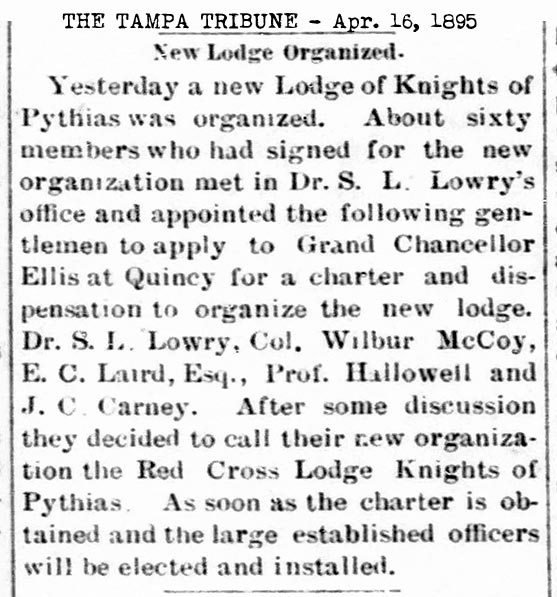

On April 16,

1895, a new Lodge of the Knights of Pythias was organized in

Tampa. About sixty men met in Lowry's office and

appointed five men to apply to the Grand Chancellor at Quincy,

Fla. for a charter and dispensation to organize the new lodge.

Dr. Lowry was among the five chosen, and after some discussion

they decided to call their new organization the Red Cross

Lodge Knights of Pythias. Plans were to elect officers

as soon as the charter was obtained. |

|

|

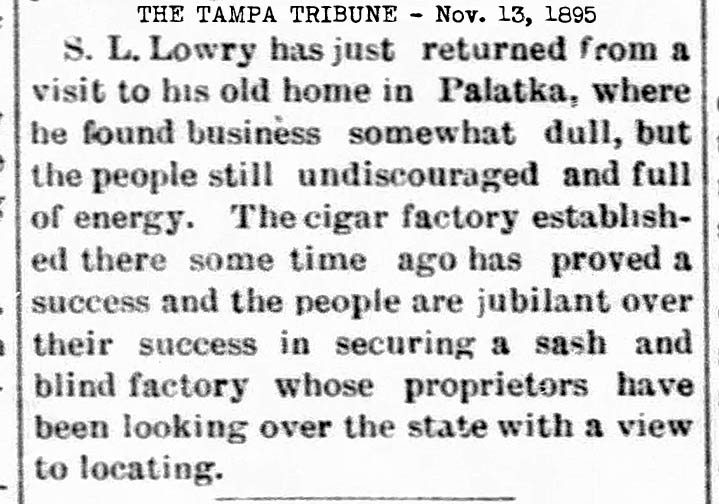

Nov. 13, 1895 - Lowry made a

trip to his old home in Palatka and found business in town to

be rather dull. A cigar factory established there

earlier proved to be a success, and the residents were

jubilant in their success of getting a sash and blind factory

located there.

|

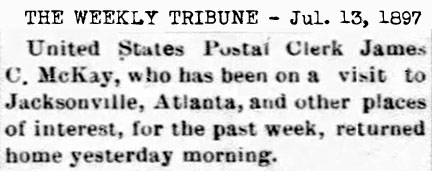

JAMES CRICHTON McKAY

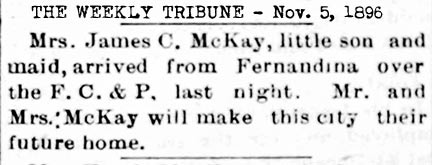

In 1896, James C. McKay's wife,

young son, and maid came to Tampa from Fernandina, Fla. with

the intent to live here. James C. McKay was a son of Capt.

James McKay, Jr. and Mary Elizabeth Crichton McKay.

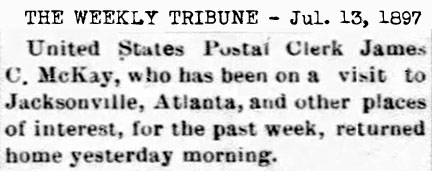

James C. was a U.S. Postal Clerk and returned to Tampa in July

the next year, after visiting other cities in the south.

LOWRY AND JAMES C. McKAY

FORM "LOWRY & McKAY"

Although no articles or ads

could be found for this agency, it was likely around this time that James C. McKay

joined Dr. Lowry in the insurance business as "Lowry and

McKay." This is brought to light by an 1898 article

forthcoming.

|

|

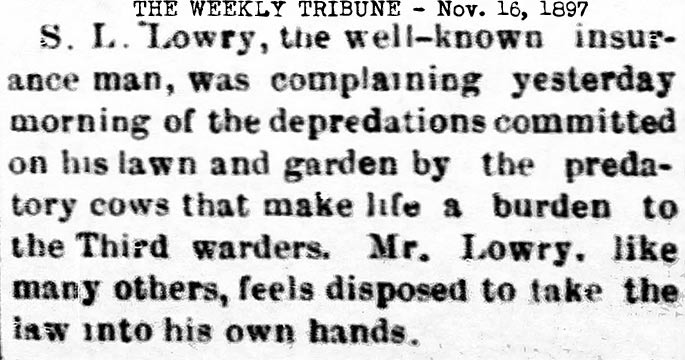

DR. LOWRY'S

COW PROBLEM

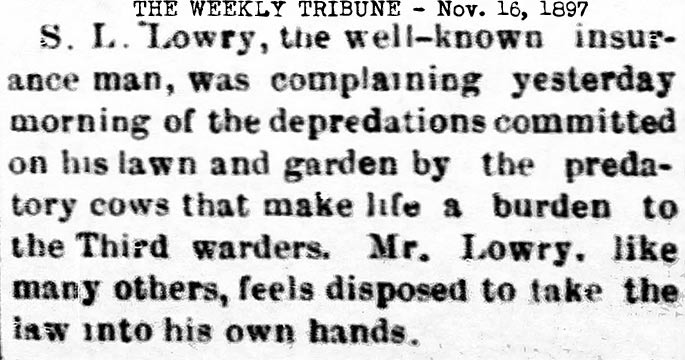

Nov. 16, 1897 - Lowry

complained about the "depredations committed on his lawn and

garden" by the roaming cows in the 3rd Ward of the city.

He was tempted to take the law into his own hands. |

|

|

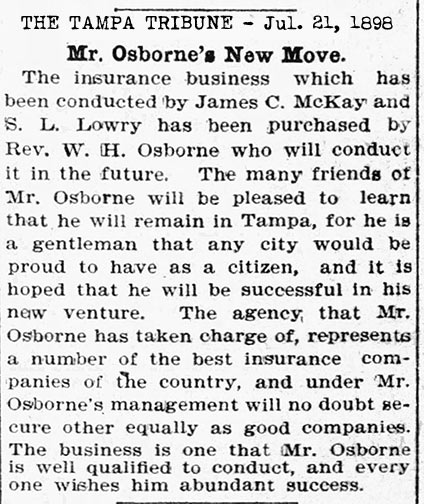

LOWRY

JOINED BY W.H. OSBORNE

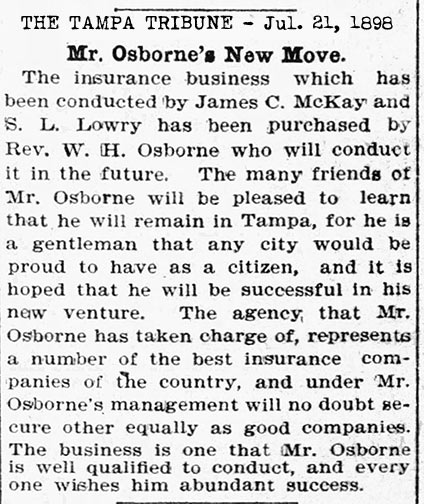

In July of 1898, W. H. Osborne, a minister at the First

Baptist Church in Tampa, bought out James C. McKay's

interest in the firm of Lowry and McKay, an agency that

represented "a number of the best insurance companies of the

country." |

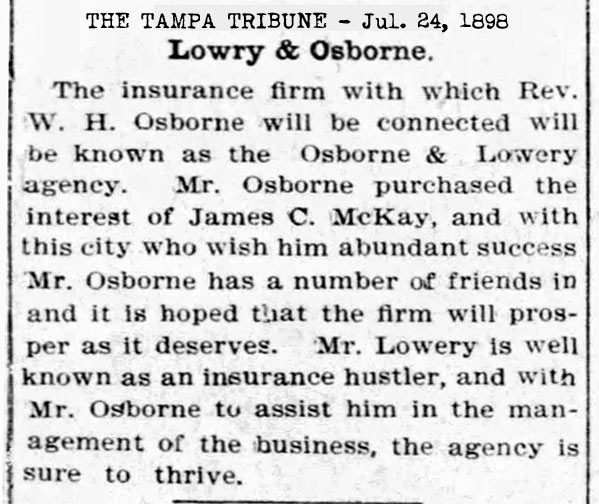

LOWRY

PREVIOUSLY PARTNERED WITH J.C. MCKAY

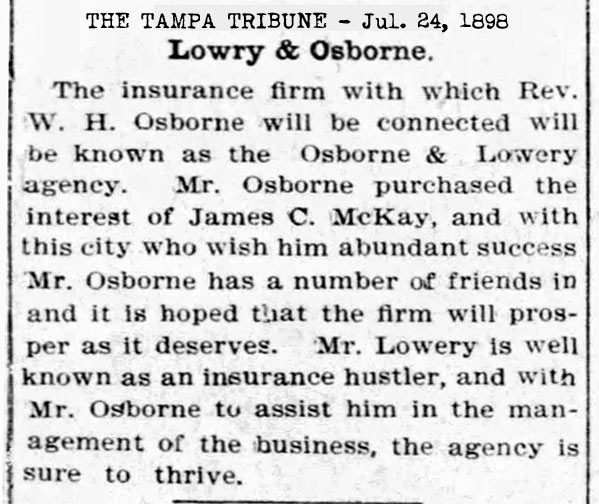

Three days later, this article appeared, which not only

misspelled Lowry's name, it calls the new partnership by two

different names--Lowry & Osborne, the Osborne & Lowery.

The correct

name was Lowry & Osborne. |

|

|

|

|

LOWRY & OSBORNE- AGENTS FOR THE OLIVER

TYPEWRITER |

|

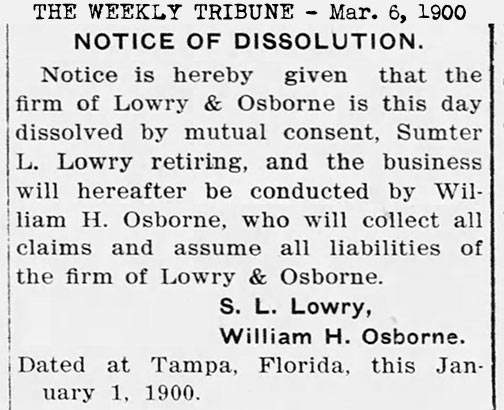

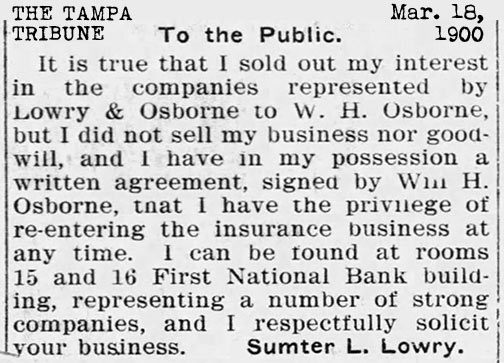

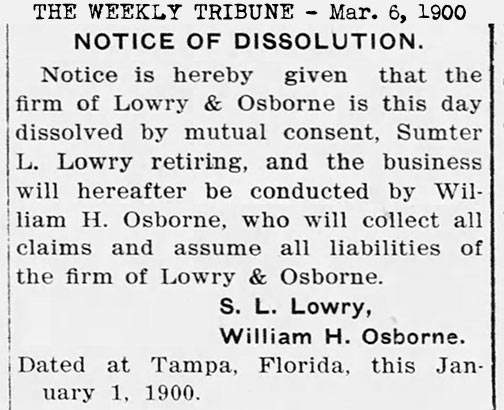

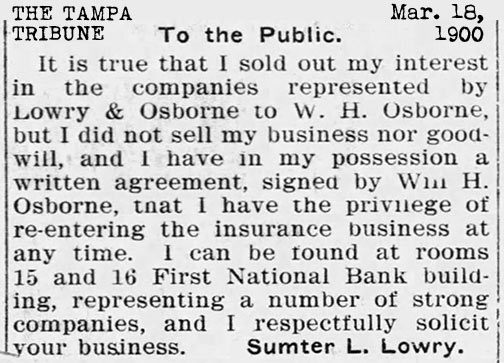

LOWRY & OSBORNE DISSOLVED

Less than two years after announcing their partnership,

notice was given that the firm was dissolved by mutual

consent and that Lowry was retiring. Clarifications

are published soon afterward that Lowry only sold out his

interest in the companies that Lowry & Osborne represented,

and he had the privilege to re-enter the business at any

time -- which he did. |

|

|

|

|

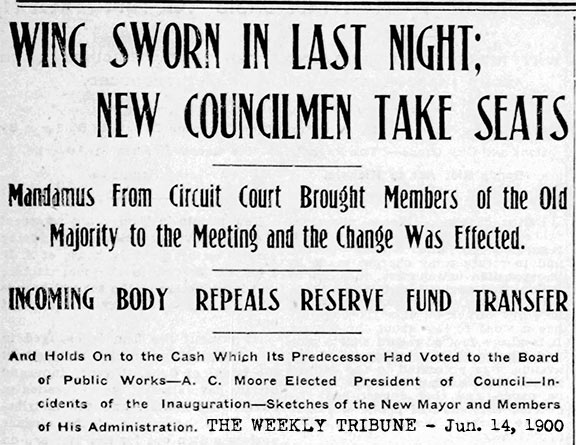

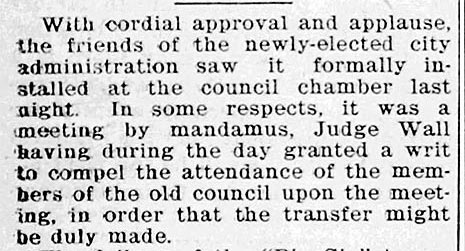

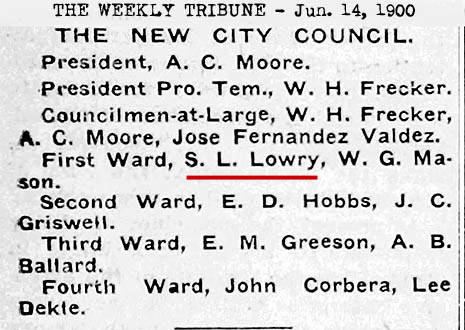

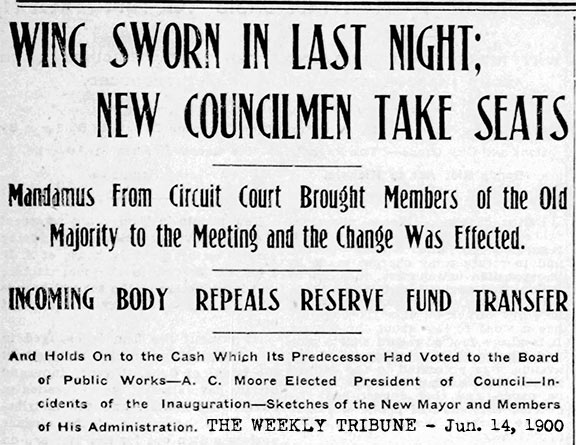

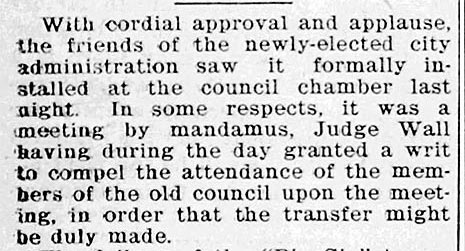

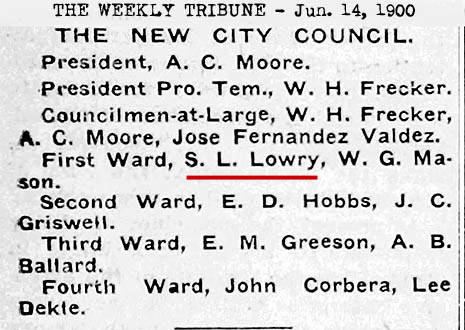

A NEW MAYOR AND CITY COUNCIL TAKE OFFICE

June 14, 1900: A new Tampa mayor is sworn in,

Frank L. Wing, and S.L. Lowry has a seat on the new city

council as one of the two representatives of of the 1st

Ward. |

|

|

|

|

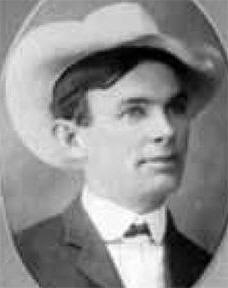

Francis

Lyman Wing

33rd And 37th Mayor Of Tampa

Born: May 9,

1868 Died: October 29, 1941

First Term:

June 8 1900 - June 4, 1902

Second Term:

June 5, 1908 - June 6, 1910

Francis "Frank" Wing

arrived in Tampa in 1889 where he opened a furniture store

and a laundry. Later, he became a successful real estate

developer. In 1922, he built the Puritan Hotel in the Hyde

Park district. He was also the director of the Lyons

Fertilizer Company.

In 1892, Wing

married Annie E . Hale, who had lived in Tampa since the age

of one. The following year, they built a house on north

Morgan Street where the couple raised their children. Wing

was a member of the City Council during the Spanish-American

War and served from June 1898 to June 1900. |

|

|

Wing ran

unopposed for mayor as the Citizens’ League candidate in

June 1900. During Wing’s first administration, Tampa

benefited from a steady population growth, due in part by

the economic prosperity from cigar manufacturing in Ybor

City, phosphorus export, and the Port of Tampa (Port Tampa

City 1893 – 1961). The population growth placed an enormous

strain on public works and services. In response, Wing and

succeeding mayors embarked on capital projects to improve

and expand the City’s public works and services to the

community. |

Mayor Wing info and

photo from "The Mayors of Tampa, 1856 - 2015" a project of

the City of Tampa

|

|

|

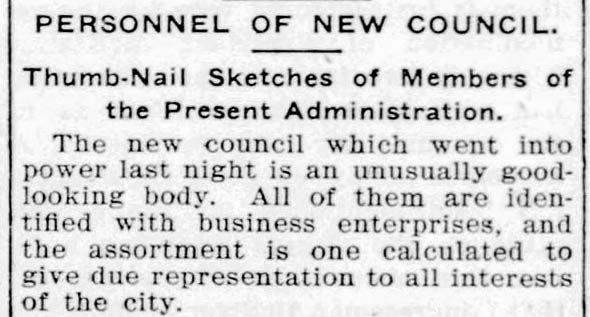

GET TO KNOW THE CITY COUNCIL |

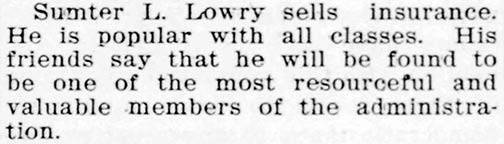

| The Tribune provides "Thumb-Nail

Sketches" of the new members of the City Council. A short

paragraph or two for each one, mostly about their occupations.

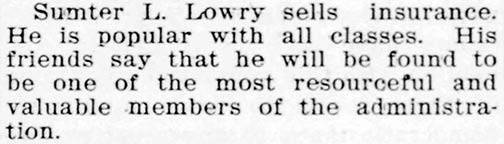

For S. L. Lowry, they wrote:

|

|

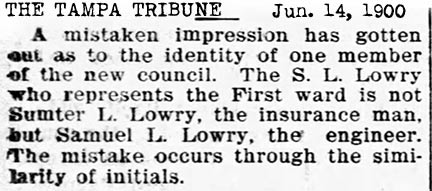

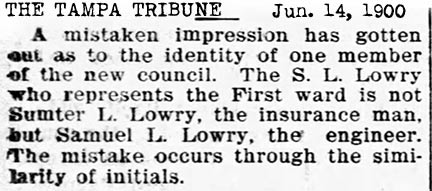

But the Tribune

described the wrong S.L. Lowry in the "thumb-nail sketch."

Without admitting it was their mistake, they informed the public that the S.L. Lowry who is on the new

city council was not the insurance man, Sumter L. Lowry. The

council member was Samuel L. Lowry, an engineer.

(Yet, future articles about Sumter Lowry continued to use "S.L. Lowry.")

|

|

|

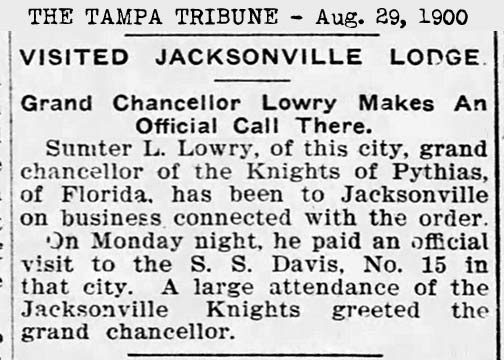

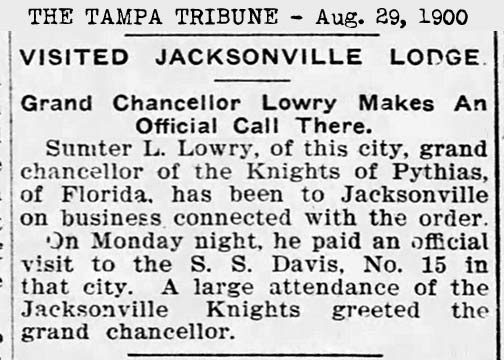

LOWRY IS GRAND CHANCELLOR OF THE

KNIGHTS OF PYTHIAS OF FLORIDA

|

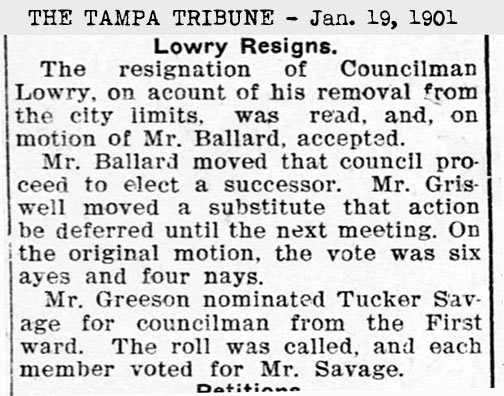

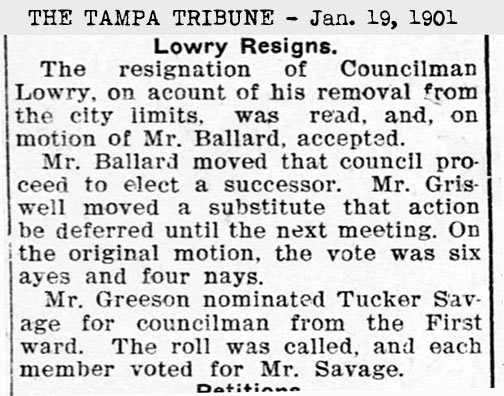

CITY COUNCILMAN

SAMUEL L. LOWRY RESIGNS

Councilman Lowry, the

engineer, moved out of the city limits and so had to resign.

This should end the confusion.

|

In the next 5 years or so, Lowry would be mentioned hundreds of times in

the papers. Most articles were either about his success as an

insurance salesman, or his involvement with the Knights of Pythias

Lodge. Almost as many were about his wife and her involvement with

society events and charities.

Here is a small sample of the types of

articles mentioning Sumter L. Lowry:

|

Mar.

1901 - Lowry is the Grand Chancellor of the Florida Pythian lodges |

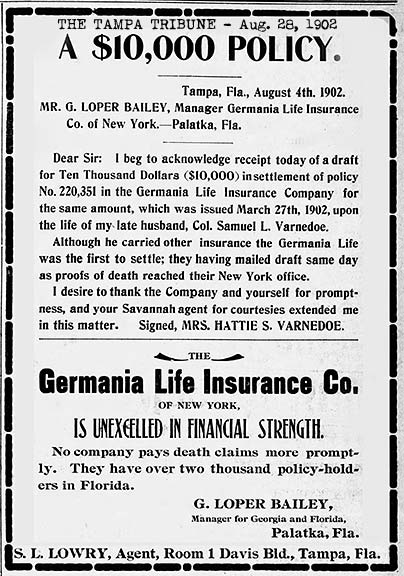

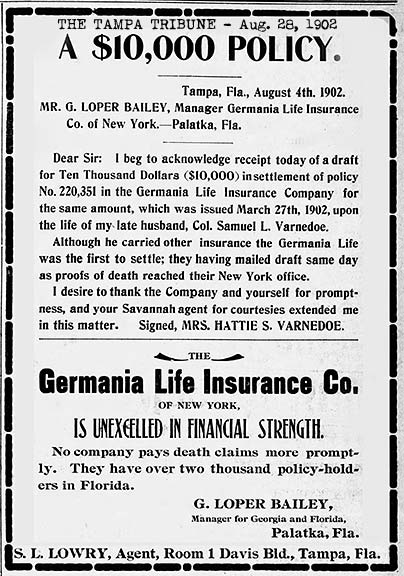

Aug.

1902 - Testimonial letter for prompt payment of a large claim.

Lowry's office at 1 Davis Blvd. is not Davis Islands. It didn't

exist until 1925. |

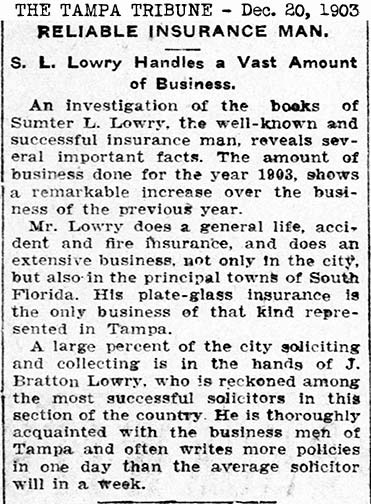

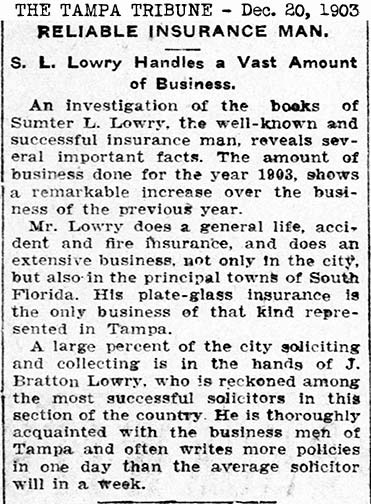

Dec.

1903 - Lowry's business has remarkable increase over previous year.

He employs his nephew, J. Bratton Lowry. |

|

|

|

|

|

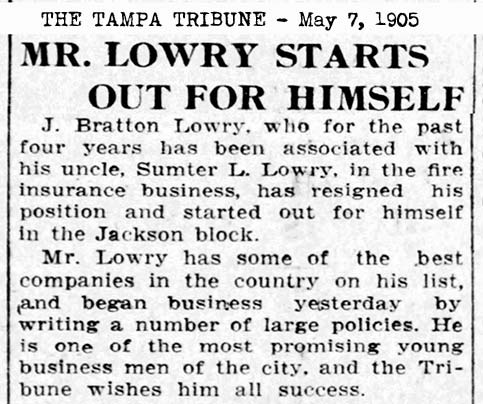

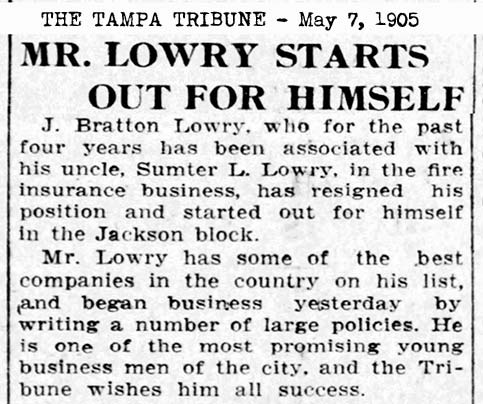

May

1905 - Lowry's nephew resigns and starts his own business on Jackson

block. |

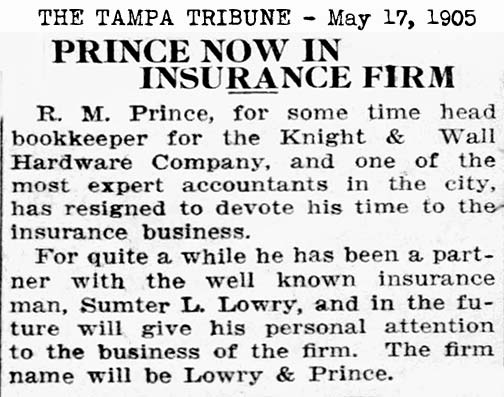

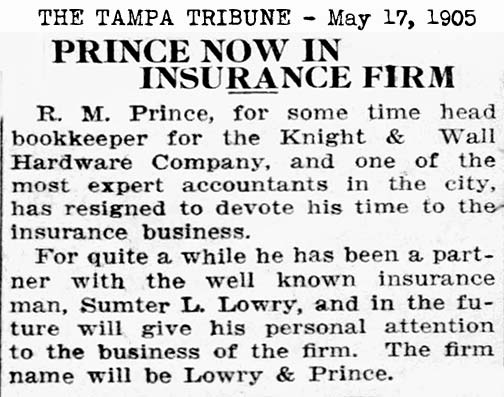

May

1905 - R.M. Prince, accountant with Knight & Wall Hardware, joins

Lowry firm. |

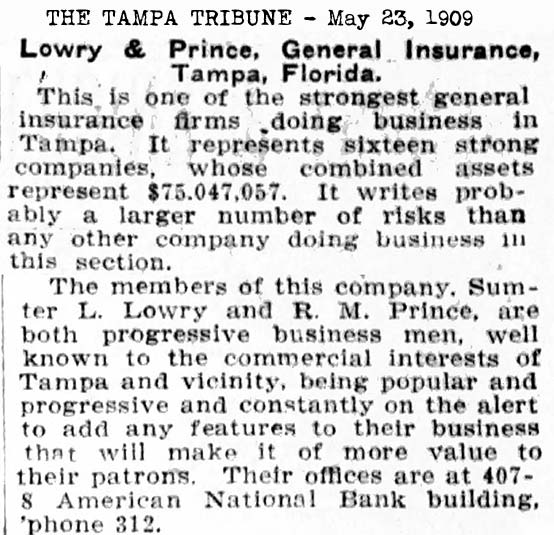

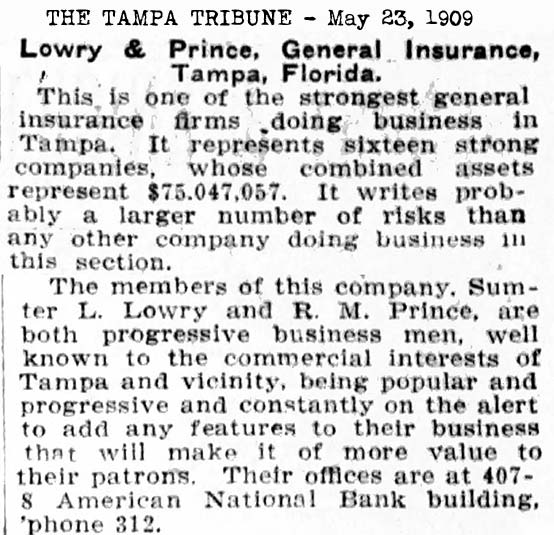

May

1909 - Lowry & Prince one of the top insurance companies in Tampa. |

|

|

|

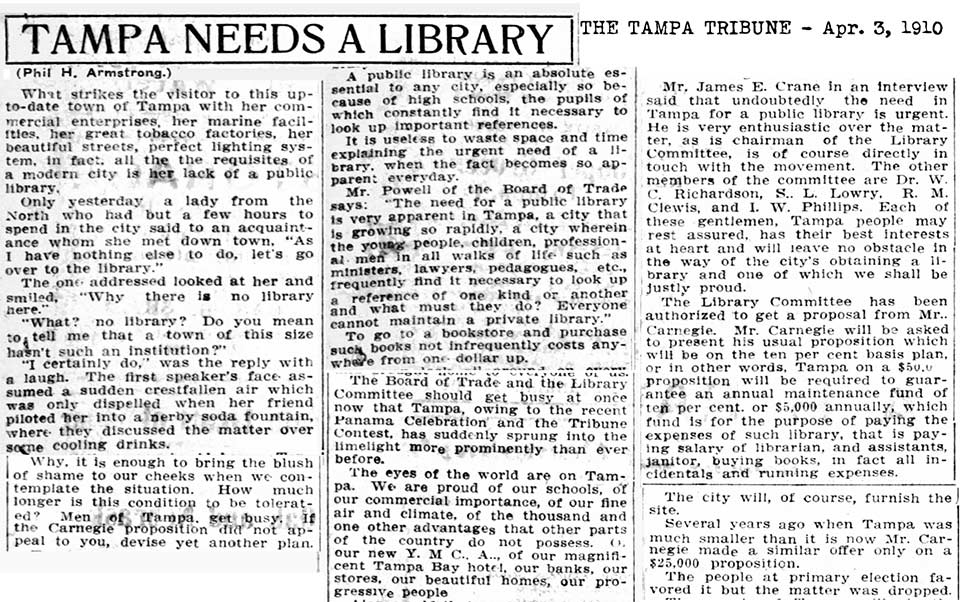

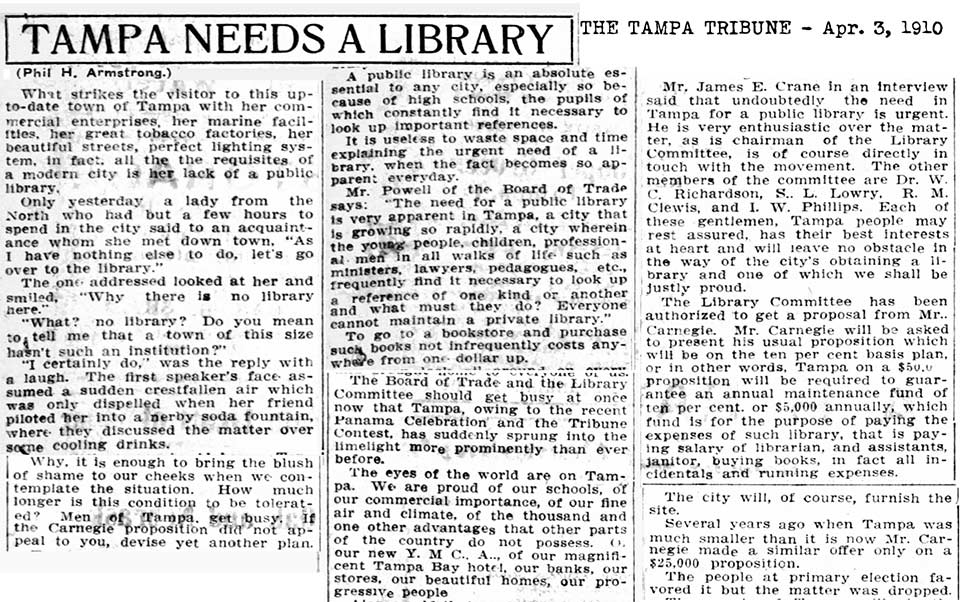

| TAMPA PUSHES FOR A CARNEGIE

LIBRARY A significant

event in the history of Tampa was the procurement of its first

public library.

Many Americans first entered the worlds of information and

imagination offered by reading when they walked through the front

doors of a Carnegie library. One of 19th-century industrialist

Andrew Carnegie’s many philanthropies, these libraries entertained

and educated millions. Between 1886 and 1919, Carnegie’s donations

of more than $40 million paid for 1,679 new library buildings in

communities large and small across America. Many still serve as

civic centers, continuing in their original roles or fulfilling new

ones as museums, offices, or restaurants.

Carnegie Libraries: The Future Made Bright, National Park Service

website

Andrew

Carnegie was once the richest man in the world. Coming as a dirt

poor kid from Scotland to the U.S., by the 1880s he'd built an

empire in steel — and then gave it all away: $60 million to fund a

system of 1,689 public libraries across the country. A total of 2,509

Carnegie libraries were built between 1883 and 1929, including some

belonging to public and university library systems. 1,689 were built

in the United States, 660 in the United Kingdom and Ireland, 125 in

Canada, and others in Australia, South Africa, New Zealand, Serbia,

Belgium, France, the Caribbean, Mauritius, Malaysia, and Fiji. At

first, Carnegie libraries were almost exclusively in places where he

had a personal connection - namely his birthplace in Scotland and

the Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania area, his adopted home-town. Yet,

beginning in the middle of 1899, Carnegie substantially increased

funding to libraries outside these areas. In later years, towns that

requested a grant and agreed to his terms were rarely ever refused. By the time the last grant was made in 1919, there were 3,500

libraries in the United States, nearly half of them built with

construction grants paid by Carnegie.

In order to pursue the

goal of obtaining a Carnegie Library in Tampa, a committee of six

men were chosen. Chairman James E. Crane, Dr. W.C. Richardson,

Sumter L. Lowry, R.M. Clewis, and Isham W. Phillips (namesake of

Tampa's Phillips Field.)

Below are excerpts

from a very long article.

See whole library article |

|

|

|

Nearly all of Carnegie's

libraries were built according to "the Carnegie formula," which required

financial commitments from the town that received the donation. Carnegie

required public support rather than making endowments because, as he

wrote:

"An endowed institution is liable to become the prey of a clique. The

public ceases to take interest in it, or, rather, never acquires

interest in it. The rule has been violated which requires the recipients

to help themselves. Everything has been done for the community instead

of its being only helped to help itself."

So Carnegie required the

elected officials—the local government—to:

-

Demonstrate the need

for a public library

-

Provide the building

site

-

Pay staff and maintain

the library

-

Draw from public funds

to run the library—not use only private donations

-

Annually provide ten

percent of the cost of the library's construction to support its

operation

-

Provide free service to

all.

Carnegie assigned the

decisions to his assistant James Bertram. He created a "Schedule of

Questions." The schedule included: Name, status and population of town,

Does it have a library? Where is it located and is it public or private?

How many books? Is a town-owned site available? Estimation of the

community's population at this stage was done by local officials, and

Bertram later commented if the population counts he received were truly

accurate, "the nation's population had mysteriously doubled."

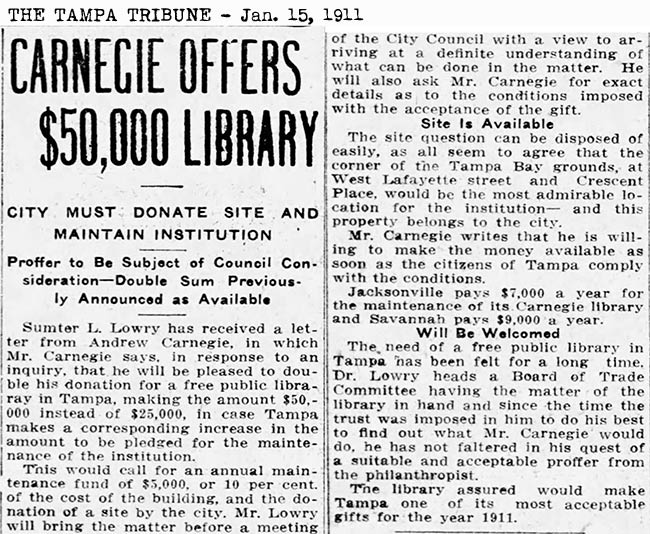

Tampa planned to request a

contribution of $50,000 from Carnegie. The usual Carnegie

proposition was the 10% plan, so it would require Tampa to guarantee

$5,000 of annual funding for the library. This included paying

such library expenses as salary of a librarian and assistants,

janitor, purchase of books, and all incidentals and running

expenses. Several years earlier, Tampa made a similar offer on a

$25,000 proposition. Tampa's citizens voted for it in the

primary, but the matter was then dropped.

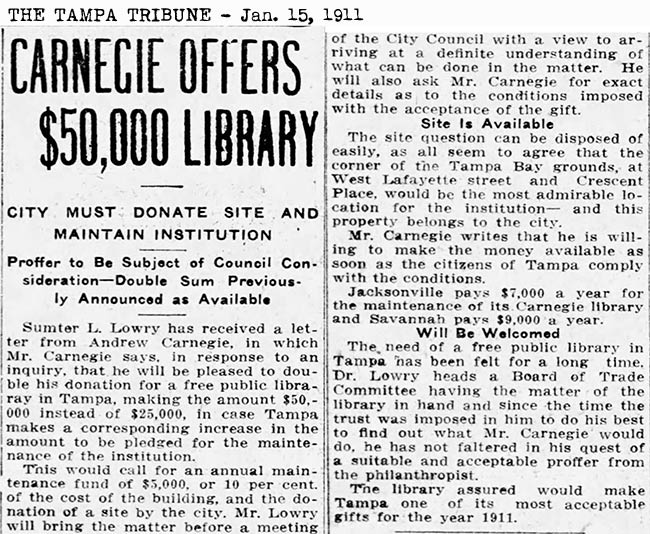

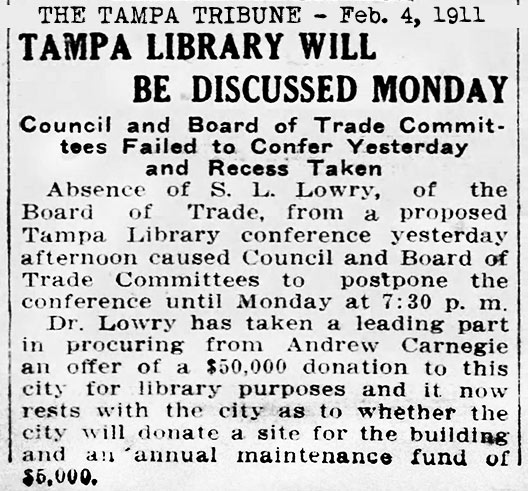

Lowry received a

response from Carnegie stating that he would be pleased to double

the previous donation amount to $50,000 and would make the funds

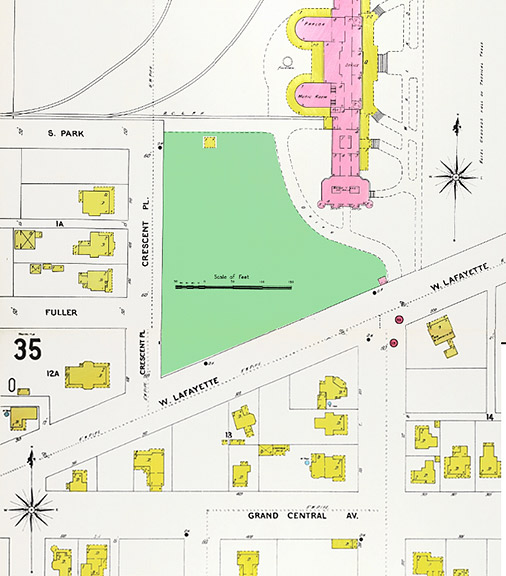

available as soon as Tampa complied with the conditions. "All

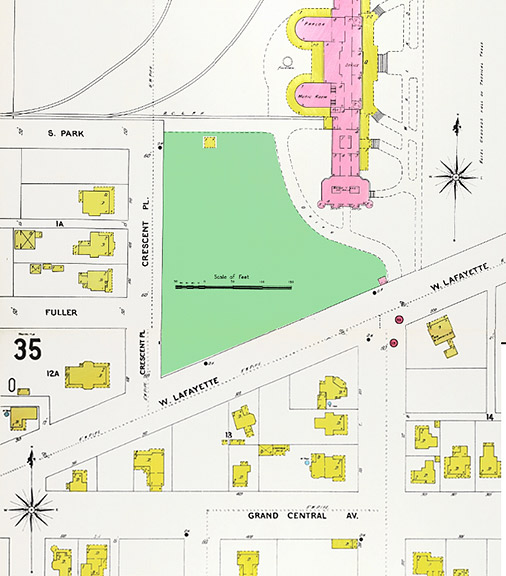

seem to agree that the corner of the Tampa Bay [Hotel] grounds, at

West Lafayette St. and Crescent Place would be the most admirable

location for the institution -- and this property belongs to the

city. (See green area on 1903 Sanborn map below.)

|

|

|

Carnegie Library from Wikipedia

How Andrew Carnegie Turned His Fortune Into A Library Legacy, by NPR's

Susan Stamberg

Always actively

interested in civic affairs, Dr. Lowry was one of the organizers and

the first president of the Commission Government Club of Tampa, and

when that form of government was adopted, was elected as one of the

commissioners, serving six years. While in office he took a leading

part in the purchase of the waterworks by the city, the installation

of the waterworks plant, the improvement of the harbor, the building

of the Municipal Hospital, the rehabilitation of Tampa Bay Hotel,

the building of five bridges, and the building of the beautiful

Bayshore Blvd.

A member of the Episcopal Church, he helped to raise funds for

the building of St. Andrews and was one of the founders of St.

John’s church. He was a delegate to the general conference of

Episcopal churches in 1928. He was a past grand chancellor of the

Knights of Pythias, a president of the Florida State Fire

Underwriters Association, and Commander in Chief of the National

Sons of Confederate Veterans.

Dr. Lowry married in SC to Willie Miller, of Raleigh, NC, in

1889.. During her

lifetime she was one of Tampa’s most earnest women workers. Included

among the organizations and institutions which she initiated and

supported were the Women’s Club, the YWCA, the Woman’s Exchange

Club, the Red Cross, the Colonial Dames and the American Legion

Auxiliary. She was one of the leaders in the campaign to acquire the

Tampa Public Library. Following her death, the Tampa Tribune stated

in an editorial that Mrs. Lowry “was the most active and effective

woman civic worker Tampa ever knew…she supplied most of the energy,

organizing ability and brains which figured in the cultural,

intellectual and social development of the city.” Mrs. Lowry died in

August, 1946 at the age of 85

Five children were born to Dr. and Mrs. Lowry: Willie Louise (Mrs

Vaughan Camp), Sumter L (Jr.), Blackburn W., Loper B., and the late

Isabella (Mrs. George Scott Lazare). Dr. Lowry died in May, 1934 at

the age of 75.

In 1910, McKay was elected to his first term

as Mayor of Tampa and served for 10 years in the position. In 1927, McKay ran for a four year term and

was overwhelmingly elected, raising his tenure as Mayor to a total of 14

years (1910-1920, 1927-1931).

During his years as mayor, McKay

implemented a massive expansion infrastructure in public works projects - streets were

paved, sidewalks built and sewer systems constructed throughout the city.

In addition, construction on City Hall was completed (1915), the third

(final) Lafayette

Street (Kennedy Boulevard) Bridge was completed, Tampa's first public

library opened (1917), brick fire stations were built as were the main

buildings for the South Florida Fairgrounds. All were accomplished with

McKay's oversight.

In 1918, Dr. Lowry urged the city

of Tampa to buy land north of Sligh Avenue at North Blvd and dedicate it for use as

a public park. (Some sources say he donated the land and suggested a

park be built.) Around 1925, after years of hard work, it became a

reality, and the park was later named in Lowry's honor. Sumter L. Lowry, Sr. died in

1934 at age 75.

|

Sumter

L. Lowry participated in the events, one of which was a

one-on-one competitive drill with Dwight Wilson. Both

competitors were equal to the task, but "fortune finally

smiled" in favor of Wilson, who received a medal.

Sumter

L. Lowry participated in the events, one of which was a

one-on-one competitive drill with Dwight Wilson. Both

competitors were equal to the task, but "fortune finally

smiled" in favor of Wilson, who received a medal.